Slay by Laurell K. Hamilton Summary, Characters and Themes

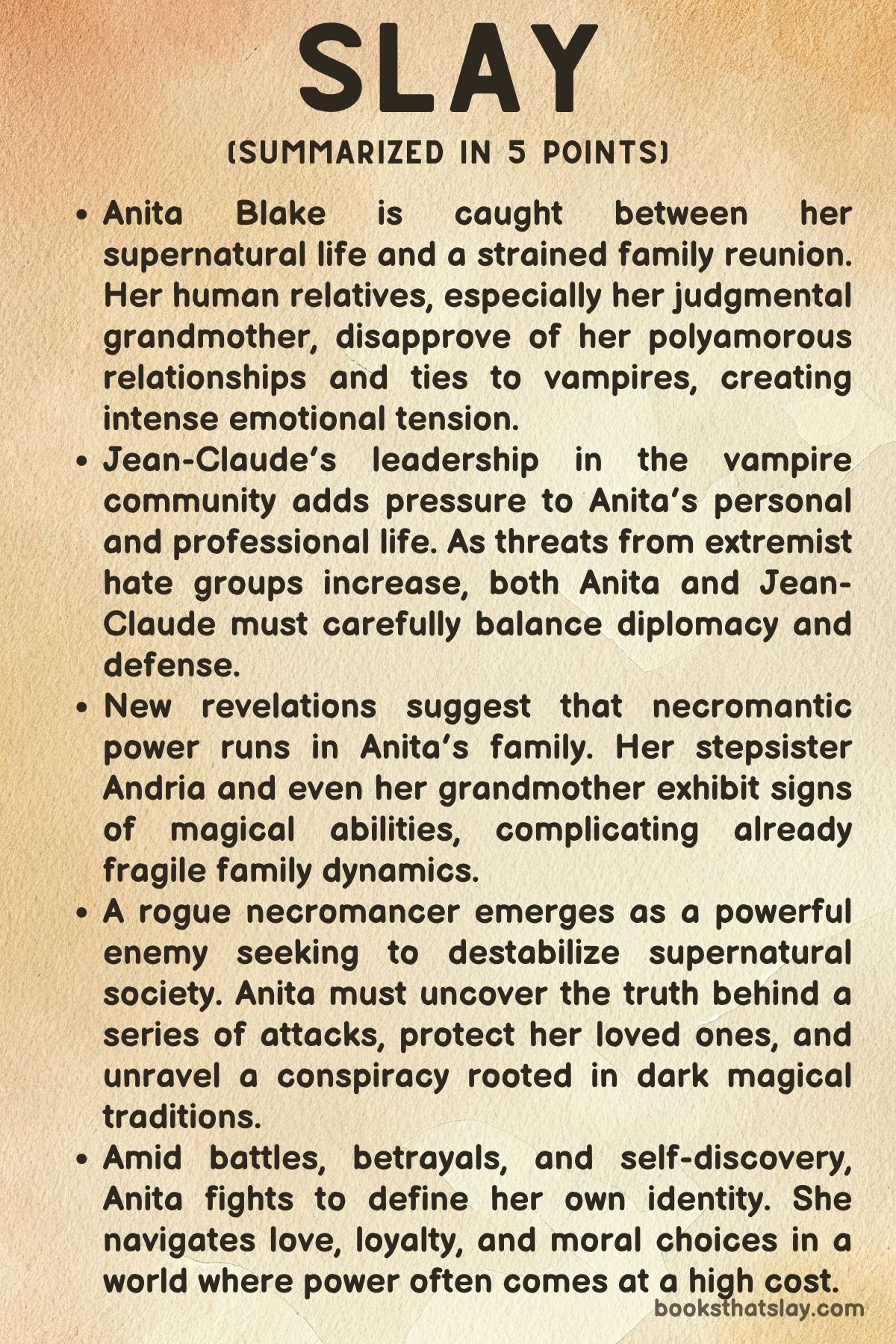

Slay is a dark urban fantasy novel from Laurell K. Hamilton’s long-running Anita Blake, Vampire Hunter series. At its core, it’s a complex exploration of identity, power, and family, all set against the backdrop of supernatural intrigue and societal tensions.

Anita Blake, a necromancer and federal marshal, finds herself navigating an emotional minefield when her estranged human family visits, threatening to unravel the balance she’s maintained between her personal and supernatural lives.

As political tensions rise in the vampire world and a dangerous rogue necromancer emerges, Anita must protect not only the lives of those she loves but also the very fabric of the supernatural order.

Summary

Anita Blake waits anxiously at the airport for her estranged family—her father Fredrick, stepmother Judith, stepsister Andria, and deeply religious Grandma Blake. The visit is meant to be a chance for reconciliation, but Anita is on edge.

She is engaged to Jean-Claude, the vampire king of St. Louis, and maintains a polyamorous relationship with several partners, including Nicky and Micah. Her family’s conservative beliefs and judgmental attitudes immediately cause tension, especially from Grandma Blake, who condemns Anita’s lifestyle and supernatural affiliations.

Despite Anita’s efforts to set boundaries, her grandmother forces herself into family events, including a critical dinner with Jean-Claude. Jean-Claude plays the diplomat, managing to win over Judith and partially soften Fredrick.

However, the dinner is overshadowed by supernatural undercurrents. Anita suspects her grandmother might harbor a suppressed form of necromantic power—something Grandma Blake vehemently denies, instead cloaking it in religious shame.

As threats against the supernatural community escalate—fueled by a hate group targeting vampires and whispers of a rogue necromancer—Anita is pulled between protecting her family and fulfilling her duty. Tensions rise when Andria begins showing signs of necromantic sensitivity herself, further complicating family dynamics.

Anita is torn between shielding her stepsister from this dangerous world and mentoring her through it. Jean-Claude faces political pressure from rival vampire factions who view his relationship with Anita as a risk to their sovereignty.

Meanwhile, Asher, Jean-Claude’s emotionally unstable companion, suffers a public attack that reveals the growing boldness of their enemies. Personal drama escalates as Richard, Anita’s werewolf ex, resurfaces, upset with decisions made in her romantic and political spheres.

Multiple supernatural attacks ensue—including an attempted breach of the Circus of the Damned and a terrifying siege of Anita’s mansion by animated corpses. Each event strengthens Anita’s suspicions that a powerful death mage is orchestrating these moves.

Clues begin to point toward a cult called the “Veil-Blooded,” an extremist group seeking to resurrect a hybrid vampire-god through blood magic and sacrifice. As Andria’s powers grow, Anita reluctantly begins training her.

It becomes clear that the ability to raise the dead affects Andria emotionally. Grandma Blake experiences terrifying visions and can no longer deny her own magical affinity.

She finally admits that her lifelong “visions” might be more than just spiritual temptations—they are manifestations of death magic long repressed. Allies from witch covens, law enforcement, and preternatural communities gather.

Anita uncovers that the cult’s leader is Father Gabriel DeMont, a former Vatican exorcist who turned to forbidden necromantic practices. He believes resurrecting the vampire-god will cleanse the world of supernatural sin.

Anita’s team locates the cult in an abandoned church crypt mid-ritual and stages an assault. A fierce battle erupts.

Anita raises her own undead army, Jean-Claude channels ancient vampire power, and Grandma Blake uses her awakened death magic to sever a blood tether and save Andria. As the ritual peaks, DeMont tries to possess Jean-Claude’s body.

Anita’s emotional and magical strength—bolstered by Andria and Grandma Blake—halts the ritual and implodes DeMont’s power from within. In the aftermath, Anita’s family begins to accept her truth.

Fredrick and Judith offer tentative support. Andria chooses to study necromancy responsibly under Anita.

Grandma Blake, forever changed, returns home—no longer in denial of her power or her granddaughter’s world. Anita and Jean-Claude, bonded more deeply by the trials, reflect on the battles behind them and those yet to come.

They find solace in a quiet moment of unity and understanding.

Characters

Anita Blake

Anita Blake remains the complex, morally nuanced heart of Slay. As a necromancer, Federal Marshal, and the fiancée of the Vampire King Jean-Claude, she is constantly torn between multiple worlds—human and supernatural, professional and personal, logical and emotional.

Her defining characteristic is her unflinching loyalty to her principles and loved ones, even when they put her at odds with family, institutions, and society at large. In Slay, Anita confronts long-buried family trauma through the reintroduction of her estranged relatives, especially her emotionally abusive grandmother.

These interactions reveal a raw vulnerability beneath her formidable exterior. Her role as a protector extends to everyone in her sphere—her polyamorous partners, supernatural allies, and even the family who has often judged her harshly.

Yet, what makes Anita’s character compelling is her continuous inner interrogation. She questions her own morality, her place in a changing world, and the responsibility that comes with immense power.

She does not simply embody strength. She embodies the cost of it.

Jean-Claude

Jean-Claude, the vampire king and Anita’s fiancé, is elegance incarnate. Beneath his charm lies a shrewd and deeply strategic mind.

His presence in Slay is as both a lover and political player. He balances public diplomacy with private tenderness, showing respect to Anita’s family even when they insult him, and supporting her through each painful revelation.

Jean-Claude’s commitment to partnership is central to his arc—he doesn’t try to control Anita but instead empowers her. Even when her choices carry risks to his rule or reputation, he remains supportive.

His relationships with other characters, particularly Asher and Richard, add emotional layers to his narrative. Jean-Claude’s acceptance of Anita’s identity in all its facets, especially her necromantic power and polyamory, underscores his progressive and emotionally mature stance.

He becomes a stabilizing and quietly powerful force in the chaos surrounding them.

Nicky

Nicky, Anita’s bodyguard and lover, functions as both her anchor and shadow. Fiercely loyal and physically imposing, Nicky offers more than just protection—he provides emotional ballast.

Throughout the novel, he is often the silent strength standing beside Anita. He supports her without dominating the scene.

What makes Nicky intriguing is his past: once a killer controlled by others, he now chooses his servitude out of trust and love. His arc in Slay is subtle yet essential.

He represents the evolution from coercion to consent, from being weaponized to becoming a guardian. His bond with Anita is not rooted in jealousy or hierarchy but mutual reliance.

His quiet wisdom often contrasts with the louder emotions of others in the inner circle.

Andria

Andria begins as a passive and somewhat awkward presence. She is uncertain of her role in both her family and Anita’s supernatural world.

But over the course of Slay, she transforms dramatically. She evolves from a naïve stepsister into a burgeoning necromancer in her own right.

Her arc is defined by revelation and choice—discovering her abilities, choosing to acknowledge them, and deciding to train under Anita despite the risks. Andria’s growth forces Anita to reevaluate her own mentorship abilities.

She must also confront her fears about what power can do to someone emotionally unstable or inexperienced. As Andria taps into increasingly potent magic—culminating in the accidental raising of a revenant—her arc mirrors a dark coming-of-age narrative.

She is torn between wanting to belong and fearing what that might mean. Especially in a world where necromancy is as dangerous as it is seductive.

Grandma Blake

Grandma Blake emerges as one of the most psychologically complex figures in the novel. Initially presented as a religious zealot who judges Anita’s every choice, she gradually reveals a repressed connection to death magic.

Her vehement condemnation of Anita’s life is not just moral outrage—it is also fear, projection, and denial of her own latent powers. As the story unfolds, it becomes evident that her pious rigidity masks a deep internal conflict.

Her visions, sudden magical awakenings, and eventual use of death magic to protect her family challenge her worldview. They force a reckoning with her identity.

In helping thwart the Veil-Blooded cult’s resurrection ritual, Grandma Blake begins to evolve. She sheds layers of denial and begins a tentative reconciliation with Anita.

She symbolizes the danger of self-repression. But also the possibility of transformation.

Asher

Asher is the tragic aesthete of the narrative—beautiful, tormented, and volatile. His inner turmoil stems from the scars—physical and emotional—he carries from his past.

In Slay, those wounds resurface violently after a public assault. Asher’s relationship with Jean-Claude is layered with old passion, jealousy, and abandonment.

His interactions with Anita and the rest of the inner circle are fraught with tension. His demand for attention and emotional spirals risk destabilizing the already delicate web of alliances.

Yet Asher is not a villain—he is a cautionary figure. He represents the fragility of beauty, the longing for love, and the consequences of feeling perpetually second-best.

His character adds dramatic weight and emotional unpredictability to the narrative. He teeters between redemption and relapse.

Fredrick

Anita’s father Fredrick is a figure marked by regret and slow redemption. Long complicit in Anita’s emotional trauma—especially by siding with Grandma Blake or ignoring her abuse—he begins a genuine process of self-reflection in Slay.

His attempts to reconnect with Anita are clumsy but earnest. His eventual apology marks a pivotal moment in their strained relationship.

Fredrick is also emblematic of generational change. While still tethered to certain traditional values, he makes a sincere effort to understand his daughter’s world and choices.

His evolution from passive enabler to cautious supporter enriches the family subplot. It provides emotional contrast to the supernatural epic unfolding around them.

Judith

Judith, Anita’s stepmother, begins the story as a seemingly superficial character. She appears more concerned with appearances and decorum.

However, as tensions rise, Judith reveals herself to be one of the more empathetic voices in the family. She often serves as a mediator between Anita and Fredrick.

She even attempts to soothe conflicts involving Grandma Blake. Her character arc is one of quiet support.

She’s not deeply involved in the magical drama. But her emotional intelligence becomes a bridge between Anita’s world and the rest of the family.

Judith’s gradual transformation from outsider to gentle ally adds a layer of warmth and subtle humanity. It brings balance to the otherwise charged family dynamics.

Themes

Identity and Self-Acceptance

One of the central themes in Slay is Anita Blake’s ongoing struggle for identity and self-acceptance. Throughout the narrative, Anita is caught between the expectations of her human family, the political demands of the supernatural world, and her own need to live authentically.

Her polyamorous relationships, role as a necromancer, and position within vampire and shapeshifter hierarchies challenge societal norms and religious dogma. The tension is magnified by her family’s judgment, especially from Grandma Blake, who condemns Anita’s lifestyle from a narrow, fundamentalist viewpoint.

Anita’s strength lies in her refusal to shrink herself to fit these expectations. Instead, she asserts her right to define love, loyalty, and morality on her own terms.

Her journey is not just about battling external enemies but also about embracing parts of herself that others view as dark or dangerous. This theme is enriched by the emergence of similar traits in Andria and Grandma Blake—both of whom exhibit necromantic tendencies, forcing them to reconsider their own identities.

The story thereby becomes a multi-generational reckoning with the truths people hide and the identities they suppress. Anita’s ability to survive and lead is ultimately tied to her unwavering insistence that self-worth cannot be contingent upon external validation, no matter how close or emotionally powerful the source of that pressure may be.

Family, Trauma, and Reconciliation

Family dynamics in Slay are complex, fraught with emotional tension, unresolved trauma, and moments of uneasy reconciliation. Anita’s return to her father, stepmother, stepsister, and especially her grandmother, opens a Pandora’s box of childhood pain and inherited wounds.

Her relationship with Grandma Blake is particularly intense, as it embodies years of emotional abuse, religious condemnation, and denial of supernatural truth. The presence of magic within Grandma Blake—a fact she tries to suppress—becomes symbolic of generational denial and self-repression.

Despite the anger and conflict, the novel also explores moments of healing. Fredrick’s eventual apology and Judith’s surprising support mark small but significant steps toward familial reconciliation.

The transformation is not rapid or simplistic; it is laden with setbacks and emotional exhaustion. And yet, there is an undercurrent of hope—suggesting that while family can be a source of deep hurt, it can also be a place for restoration if people are willing to listen and change.

Anita doesn’t forgive or forget easily, but she does begin to understand the brokenness that shaped her relatives. By the end of the novel, she extends protection to the very people who judged her, not out of obligation, but because she recognizes that her strength gives her the power to redefine the concept of family on her own terms.

The Ethics of Power

Power—its origins, applications, and moral ramifications—is another central theme that courses through Slay. Anita’s power is both feared and respected.

She holds the capacity to raise the dead, bind supernatural beings, and even wage war with undead armies. Yet, her ethical compass is what distinguishes her from others who possess similar abilities, particularly the rogue necromancer Father Gabriel DeMont.

While DeMont represents unbridled, fanatical ambition, Anita embodies restraint and responsibility. She constantly weighs her decisions, agonizing over the consequences they might bring to her allies, lovers, and even enemies.

Her choices are rarely clear-cut, but they are always grounded in a strong ethical framework that values consent, justice, and self-awareness. This moral distinction is brought into sharper relief through the evolution of Andria and Grandma Blake, both of whom discover their own necromantic potential.

Anita becomes a mentor figure, guiding them to recognize that power must be wielded consciously and ethically. The novel draws a fine line between those who use power to protect and those who exploit it to dominate.

In doing so, it poses broader philosophical questions: Is it the nature of power that corrupts, or the intent behind its use? Anita’s narrative suggests the latter.

She remains a figure of authority not because she seeks control, but because she shoulders the burdens that others avoid.

Religious Judgment and Personal Truth

Religion—specifically, its dogmatic interpretation—is portrayed as both a source of comfort and a mechanism of oppression. This theme is embodied most clearly in Grandma Blake, whose unwavering Christian beliefs blind her to both her own nature and the validity of Anita’s life.

She refers to vampires as “damned” and sees necromancy as a demonic curse, not a hereditary trait. This creates intense conflict with Anita, who has spent her life embracing the very elements that her grandmother condemns.

The irony is powerful: Grandma Blake herself is a latent necromancer, proving that the truth she condemns is one she shares. The book challenges the reader to consider how rigid ideology can distort reality and perpetuate cycles of shame, fear, and repression.

Religious dogma becomes a kind of self-inflicted blindness, while Anita’s broader worldview—though fraught with moral complexity—is grounded in personal truth and empirical experience. The confrontation between the two perspectives creates a dramatic narrative arc.

Particularly as Grandma Blake begins to reluctantly accept her own powers. The theme is not anti-religious per se; rather, it critiques the use of religion to justify control and suppression.

Anita’s rejection of these constraints is not just a personal rebellion—it’s an affirmation that spirituality must be reconciled with reality if it is to be genuinely meaningful.

Love as a Source of Strength

Love in Slay is multifaceted, expansive, and often unconventional. Anita’s polyamorous relationships are not framed as a spectacle, but as a legitimate and emotionally rich structure in which she finds stability, intimacy, and strength.

Jean-Claude, Nicky, Micah, Nathaniel, and others offer different forms of love—romantic, sexual, protective, emotional—and Anita draws from each to maintain her equilibrium in a world constantly seeking to unbalance her.

These relationships are marked by mutual respect and trust, not possession or control. Even amid jealousy, trauma, and external threats, Anita and her partners strive for open communication and emotional honesty.

This stands in contrast to other relationships in the novel, especially those rooted in fear or manipulation, such as DeMont’s fanatical use of blood bonds. Love is portrayed not just as a personal comfort but as a strategic advantage.

It gives Anita the emotional resilience to confront enemies, lead in battle, and resist the seductive pull of absolute power. Her romantic bonds are not distractions from her mission; they are foundational supports that make her capable of fulfilling it.

The message is clear: love is not weakness, even when it requires vulnerability. Rather, it is a form of empowerment that enables individuals to act with greater courage and moral clarity.