Small Boat Summary and Analysis | Vincent Delecroix

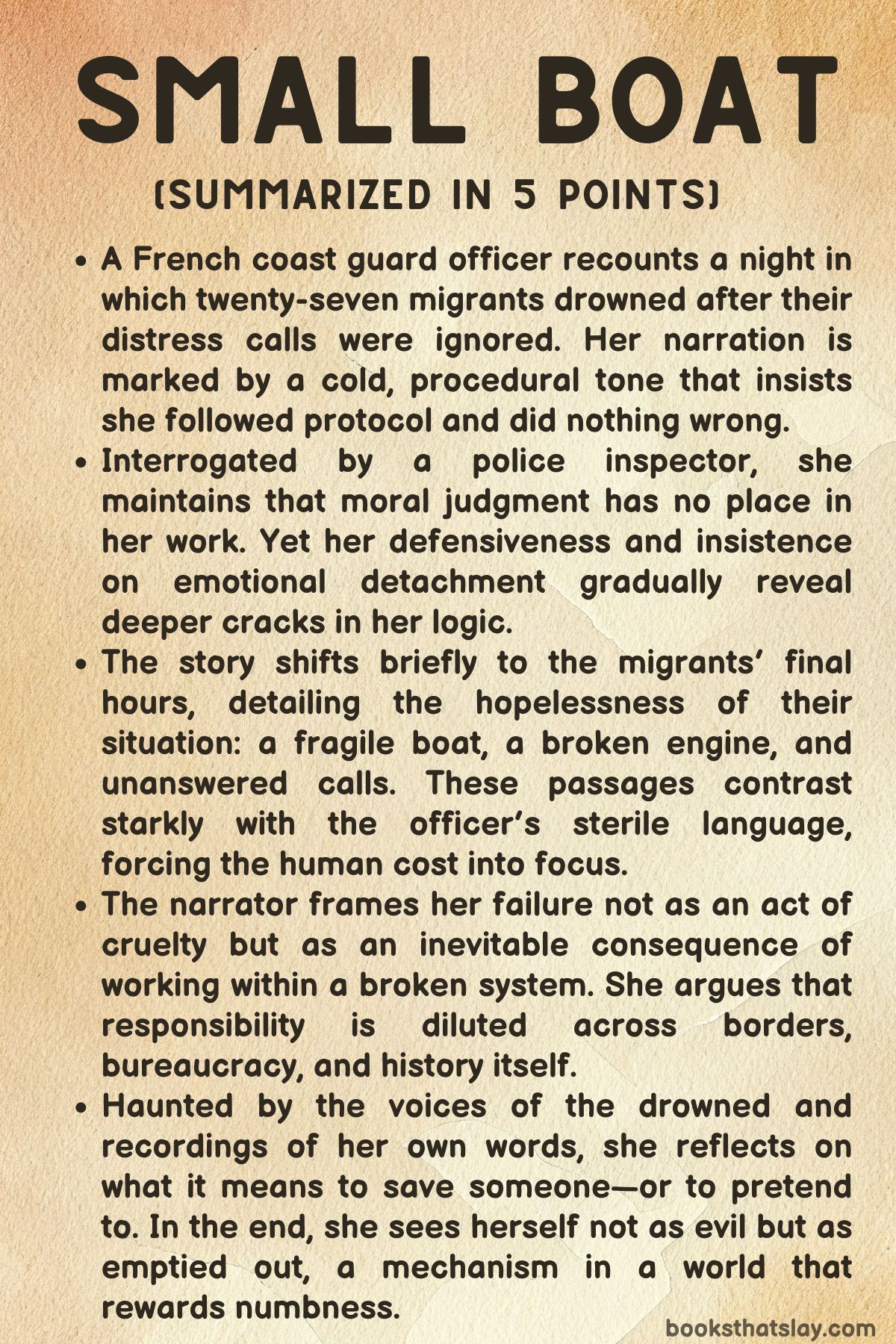

Small Boat by Vincent Delecroix is a searing, minimalist narrative that confronts the bureaucratic detachment and moral paralysis of contemporary institutions in the face of humanitarian crisis. Told through the perspective of a French coast guard officer under investigation for her role in the deaths of twenty-seven migrants in the English Channel, the book unfolds as a monologue of denial, philosophical deflection, and suppressed guilt.

Delecroix captures the existential numbness and institutional cruelty that pervade modern crisis management, where empathy is sacrificed for functionality and accountability dissolves in a sea of technicalities. Stark, uncompromising, and ethically provocative, the book questions what it means to be human in a world that treats suffering as statistical noise.

Summary

A French coast guard officer, suspended from duty, sits across from a police inspector and offers a long, fractured monologue about the deaths of twenty-seven migrants who drowned during a failed attempt to cross the English Channel. The story is structured as a conversation, but only her voice is heard.

The inspector’s questions and accusations are implied through her defensive, dispassionate replies, which gradually reveal the moral, political, and personal dimensions of the tragedy.

The narrator begins by asserting that her job does not require empathy. She describes her role at the CROSS (French maritime rescue coordination center) as purely functional: monitoring situations, following protocols, and sorting emergencies according to severity and jurisdiction.

She repeatedly insists that she did not cause the migrants to flee their homes, nor did she put them on the overcrowded rubber boat. Her duty, she says, is not to feel but to process—to serve the system, not to question it.

Despite her insistence on detachment, her language betrays her unease. She recalls the incident in increasingly personal detail: the boat drifting in the middle of the Channel, the engine failing, the migrants repeatedly calling for help.

She heard their voices, especially one man who kept calling. She responded, telling him help was coming.

She now replays those recordings, questioning whether the phrase was a comfort or a lie. She wants to believe she did her best, but the inspector pushes her toward something deeper—toward confronting the difference between failure and abandonment.

She is accused of misleading the British authorities, failing to dispatch the nearest patrol boat, and intentionally withholding critical information about the dinghy’s condition. She denies wrongdoing, arguing that the situation was murky, the boat was in international waters, and resources were stretched.

She questions the logic of assigning national responsibility at sea, where borders blur and accountability disappears. But the inspector persists, calling her not merely negligent, but inhuman—a “monster” who stood by as people drowned.

This accusation stings. It recurs in her mind.

She begins to describe how she has been haunted by the voices of the dead, especially the man who kept calling. She envisions him standing on the shore, appearing in crowds.

She runs along the beach and imagines their final moments—cold, terrified, believing rescue was near. The imagery becomes more physical and more desperate, suggesting that her detachment has cracked.

Still, she resists the label of villain. She invokes philosophical questions to justify her numbness.

Is evil an action, or a condition? Did the migrants begin to drown that night, or the day they left their homes, victims of war, poverty, and hopelessness?

She asks whether saving them would have mattered if more would come tomorrow—another boat, another body. She says that to survive in her position, she must reduce people to numbers, to avoid the unbearable weight of compassion.

The monologue shifts to the moment of the crossing. The migrants sit crammed on a fragile boat with a failing engine, surrounded by darkness.

They begin to panic. They call for help, over and over.

The cold becomes unbearable. Some fall into the water.

The man calling from the boat becomes a recurring voice, calm yet urgent. He is told help is on the way.

But nothing arrives. They wait.

The boat drifts. The water rises.

Then silence.

Afterward, the narrator insists that she did not lie. She followed protocol.

She was tired, yes—worn down by the system, by the repetition of death and desperation. She says the system is inhuman, and she is merely its servant.

But the inspector wants more than explanations. He wants moral recognition.

He wants her to see the migrants as people, not statistics. She cannot.

She says she has been trained to erase identity, to silence feeling. Otherwise, she too would drown.

In the final pages, the narrator reflects on the idea of rescue. She questions what it means to be saved, or to save.

If survival is temporary, and suffering endless, what good is one rescue? She suggests that society is less interested in action than in assurance—that we want to believe we said the right things, even if we did nothing.

Her voice returns to the man’s last call: “You will not be saved. ” The phrase echoes like a curse, both personal and political.

By the end, the narrator does not ask for forgiveness. She does not express remorse in the way the inspector desires.

But she is not unaffected. Her voice is cracked with fatigue, bitterness, and something like sorrow.

She has become, she says, a function—something less than human, shaped by a system that requires the erasure of morality in favor of efficiency. She is not a monster, but a product of a world where bureaucracy replaces compassion and survival demands emotional erasure.

Small Boat does not offer redemption or catharsis. It presents a stark examination of institutional cruelty, where responsibility is diluted and empathy is treated as a liability.

The narrator is both victim and perpetrator—someone who participated in a tragedy not out of malice, but out of habit, exhaustion, and the suffocating logic of systems that demand indifference. The story ends not with closure, but with a lingering question: in a world structured to prevent action, who is guilty—and who gets to decide?

Key People

The Narrator (French Coast Guard Officer)

The central figure in Small Boat is the unnamed narrator, a French coast guard officer whose voice carries the entire weight of the book’s moral, legal, and existential reckoning. Presented as a monologue, her perspective dominates the narrative, revealing a person at the intersection of bureaucratic obedience and human catastrophe.

Initially, she positions herself as emotionally detached, emphasizing that her job is to process information, assess maritime emergencies, and follow protocol—not to feel, judge, or act based on compassion. She argues that her duty is not to intervene emotionally but to sort crises rationally, presenting herself as a cog in a larger, indifferent machine.

This posture, however, becomes increasingly tenuous as her narration unfolds.

Despite her insistence on detachment, cracks in her composure expose deeper turmoil. Her dreams are haunted by the drowned, her memory loops the recorded phrase “Help is coming,” and she is tormented by the question of whether that lie offered hope or merely compounded cruelty.

She simultaneously distances herself from the migrants’ humanity while also being unable to erase their voices from her mind. This duality—between denial and haunted memory—underscores her psychological unraveling.

She oscillates between philosophical musings and dry procedural justifications, trying to evade guilt by couching her actions within the larger failures of policy and history. Yet her tone frequently shifts into bitterness and defensiveness, betraying an inner conflict that refuses to be fully suppressed.

The narrator becomes emblematic of a larger societal malaise: the transformation of moral beings into administrative functions. She claims she cannot afford empathy because to feel would incapacitate her.

This admission becomes one of the most chilling elements of her characterization. She is not a villain in the traditional sense, but rather a tragic figure shaped and hollowed out by systemic routines, trapped between her conscience and her conditioning.

Her ultimate failure is not only inaction but her inability—or refusal—to see the migrants as individuals. In this, she becomes both a victim and a perpetrator of institutional dehumanization.

The Police Inspector

The police inspector serves as a counterpoint to the narrator, acting as both her legal interrogator and an unwitting stand-in for the reader’s moral inquiry. While he remains largely off-stage, his presence is crucial to the dynamic of Small Boat.

He is persistent and probing, pressing the narrator not just for facts, but for a sense of personal culpability. He attempts to breach her emotional defenses by invoking empathy, asking her to consider the suffering of the drowned and her role in their deaths.

However, he fails to understand the narrator’s internal landscape, which she views as shaped not by emotion but by philosophical detachment and exhaustion.

To the narrator, the inspector represents a naive belief in the clarity of justice. She sees his approach as reductive—focused on guilt and innocence, crime and punishment—when the true horror, in her view, lies in the system’s amorality and the ambient evil of indifference.

His accusation that she is a “monster” is not just a legal or emotional judgment, but a reflection of society’s desperate need to identify human scapegoats in situations born of inhuman structures. Though morally righteous in his pursuit, the inspector appears impotent against the vast, abstract machinery that enables such tragedies.

His role, then, is not to deliver justice but to witness the limits of accountability in the face of systemic collapse.

The Drowned Migrants

While unnamed and largely silent, the twenty-seven migrants who perish in the Channel form the silent core of Small Boat. Their presence is ghostly but powerful, shaping the narrator’s monologue and haunting the emotional and moral fabric of the story.

They exist in the text as both victims and symbols—individuals fleeing violence, poverty, and despair, who are rendered faceless by the systems meant to protect or manage them. Their suffering is made achingly real through the narrator’s recollections of their calls for help, their pleas growing weaker as the cold and sea close in.

The migrants become a mirror through which the narrator confronts her own humanity—or lack thereof. She cannot allow herself to see them as people with names, families, or futures; to do so would be to shatter the psychological defenses that let her perform her duties.

Yet she is unable to fully forget them. Their voices linger, their deaths echo in her mind, and their final moments creep into her dreams.

In this way, they transcend the anonymity imposed by both the sea and the system. They symbolize the broader failure of a world that views survival as a privilege instead of a right, and they stand as a silent rebuke to every justification the narrator—and, by extension, the reader—tries to offer.

They are the moral center of the narrative, and their voicelessness speaks volumes.

Analysis of Themes

Bureaucratic Dehumanization and Institutional Indifference

The narrative presented in Small Boat is a chilling commentary on how bureaucratic systems systematically strip away empathy in favor of procedural detachment. The narrator, a French coast guard officer, functions as a cog in a larger institutional machine, operating with a mindset shaped entirely by rules, protocols, and definitions of responsibility that do not leave room for moral reflection.

Her repeated assertions that her job requires no emotional engagement—only the execution of directives—expose the moral vacuum at the heart of state systems tasked with responding to humanitarian crises. The most harrowing aspect is not just the catastrophe of the twenty-seven deaths, but the normalization of such inaction.

The coast guard officer rationalizes her behavior by citing jurisdictional limitations, resource allocation, and legal ambiguities, thereby revealing a framework that allows tragedy to be quietly absorbed and legitimized by procedure. This bureaucratic lens erases the individuality of the migrants, transforming them into numerical liabilities rather than human beings in peril.

The narrator’s insistence that she is merely a “function” and not a person underscores how deeply dehumanization is embedded in institutional culture. Her numbness becomes a defense mechanism, allowing her to continue existing within a system that rewards indifference over compassion.

In such a structure, culpability is dispersed so widely that moral clarity becomes impossible, and the machinery continues to operate, even as it fails those it purports to serve.

Moral Displacement and the Crisis of Responsibility

Responsibility, in Small Boat, is not owned—it is redirected, refracted, and ultimately lost in a sea of competing jurisdictions and rationalizations. The narrator deflects blame onto the migrants for embarking on a dangerous journey, onto other authorities for failing to act, and even onto abstract forces like war and poverty that initially displaced these individuals.

This moral displacement allows her to sidestep any personal reckoning. She sees herself as the final, accidental node in a tragic sequence far beyond her control.

Yet the story’s structure gradually dismantles this denial, especially through the police inspector’s persistent questioning and through her own inability to silence the ghosts of the drowned. Her evasiveness is not just a matter of legal defense—it is an existential retreat from the unbearable weight of witnessing and doing nothing.

The narrative interrogates whether the greatest failure was logistical or moral: was it a failure to send a patrol boat or a failure to recognize human lives as deserving of urgent action? The narrator never fully admits guilt, but her spiraling rationalizations betray a deeper awareness of complicity.

Her ultimate reduction of the dead to statistical abstractions is not only self-protective but also indicative of a broader cultural reluctance to confront systemic violence with personal accountability. In denying responsibility, she mirrors a society that demands plausible deniability over meaningful action.

The Psychological Toll of Witnessing and Complicity

Even as the narrator of Small Boat maintains an outwardly emotionless stance, her inner world reveals cracks and contradictions that point to the immense psychological toll of bearing witness to catastrophe while doing nothing. Her sleep is haunted by visions of the dead, she compulsively replays recordings of herself giving false reassurances, and she is pursued by the imagined voices of those she failed to save.

These recurring images and auditory hallucinations suggest that detachment is not impermeable—it is a fragile veneer stretched over a deep reservoir of shame, fear, and unresolved grief. The language she uses—cold, technical, overly precise—is a means of containing a reality that feels too immense and threatening to confront directly.

Yet despite all her efforts, the trauma seeps through. Her own mind becomes a courtroom, replaying her actions and inactions, asking whether her statement “Help is coming” was an act of comfort or cruelty.

In this way, the narrative exposes how complicity in harm cannot be neatly compartmentalized; it corrodes from within. The psychological damage is not only a personal struggle but also a symptom of a society that demands emotional numbness from those enforcing its cruelest policies.

The narrator’s fractured psyche becomes a mirror for collective guilt, where witnessing suffering without intervention generates a state of quiet, unbearable torment.

The Erosion of Empathy Under Structural Violence

The story reveals how sustained exposure to suffering, combined with the expectations of professional dispassion, can erode empathy until it becomes indistinguishable from hostility. The narrator’s most shocking admission is her inability—and eventual refusal—to think of migrants as individuals.

She insists that to function effectively in her role, she must not engage emotionally, must not imagine the faces or stories of those calling for help. This erosion is not depicted as a sudden transformation but as a gradual process of self-erasure, a conversion of a person into a role that demands emotional sterility.

Structural violence—expressed through laws, procedures, and command chains—requires its agents to suppress human instincts of care and solidarity. The narrator internalizes this demand, rationalizing that empathy would have endangered her ability to do her job.

However, what is laid bare is the moral cost of such emotional repression: it results in a profound alienation from others and from oneself. The final consequence is not merely the death of others, but the death of feeling, of moral intuition, and ultimately, of humanity.

In this state, the narrator becomes the embodiment of a system that prizes control over compassion and treats empathy as a liability rather than a virtue.

The Sea as a Symbol of Metaphysical Evil and Moral Chaos

Throughout Small Boat, the sea emerges not just as a physical space but as a symbolic force representing unknowable danger, indifference, and metaphysical evil. The narrator invokes the sea as a monstrous, mythic entity—one that devours lives without judgment or discrimination.

It becomes a stand-in for all that is uncontrollable, ancient, and beyond moral reasoning. This imagery reflects the narrator’s struggle to assign meaning to the tragedy.

By casting the sea as a kind of Leviathan, she externalizes guilt and fear onto a vast, impersonal force. The sea’s boundlessness contrasts sharply with the tightly regulated confines of human protocol, highlighting how bureaucratic logic falters in the face of overwhelming human loss.

Yet her evocation of the sea also reveals a desire to displace responsibility yet again—to suggest that some evils are so large, so elemental, that no one can be blamed. But this logic ultimately fails to absolve her.

Instead, it underscores the nihilism creeping into her worldview: a sense that moral order is an illusion, that rescue is arbitrary, and that the line between savior and bystander is porous and unstable. The sea, in its silent enormity, becomes both a literal site of death and a metaphor for the moral abyss that opens when responsibility is endlessly deferred.