Something Extraordinary Summary, Characters and Themes

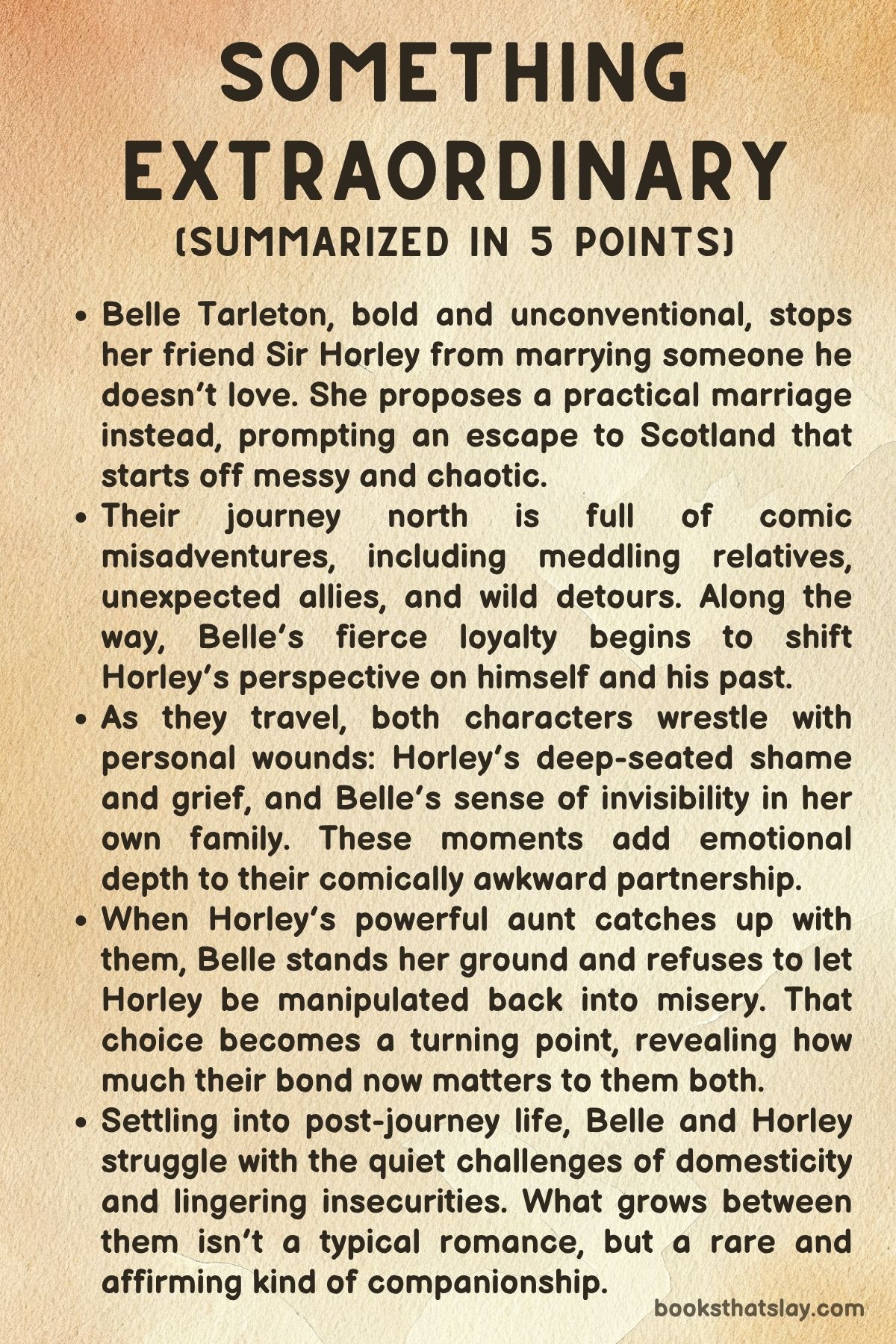

Something Extraordinary by Alexis Hall is a sharp, emotionally rich romantic comedy that challenges conventional ideas of love, partnership, and identity. Set in a society bound by rigid social roles and expectations, the story follows the unusual and deeply affecting journey of Arabella “Belle” Tarleton and Sir Horley Comewithers.

Both are misfits in their own right—Belle, a fiercely independent woman craving purpose and belonging; Horley, a man wracked by shame, queerness, and the burdens of societal judgment. Together, they create a relationship not grounded in traditional romantic ideals but in trust, loyalty, and a shared refusal to conform. Through farce, tenderness, and sharp wit, the novel navigates love in its many forms—platonic, romantic, queer, and familial—offering a refreshingly unorthodox vision of connection.

Summary

The novel opens with Arabella “Belle” Tarleton attempting to stop the wedding of Sir Horley Comewithers. Horley, drunken and self-destructive, is moments away from sealing a marriage born not of love but of obligation.

Belle, knowing Horley’s long-hidden feelings for her twin brother Bonny and the trauma he has buried beneath years of shame and repression, confronts him in his miserable state. Horley lashes out, claiming their friendship was a sham and that his life is one long performance of what is expected.

Belle, unflinching in her care, refuses to accept his self-hatred at face value and challenges his assumptions about worth, honesty, and connection.

What follows is not a romantic declaration but an unconventional proposal: Belle suggests they marry—not for love, but for solidarity. She argues that what they share, while not traditionally romantic, is deeply real.

It is a relationship grounded in mutual understanding and emotional transparency. Though Horley resists, mocking the idea at first, Belle’s conviction begins to penetrate his cynicism.

Their attempt to escape from Horley’s familial estate is both chaotic and absurd. They are pursued by Horley’s controlling aunt and his intended bride, Miss Carswile.

A wild series of comedic and humiliating incidents follows—stumbling across gardens, slipping into birdbaths, and hiding from outraged relatives. But underneath the slapstick, painful truths surface.

Horley’s aunt declares her lifelong disdain for him, affirming his deepest fears of being unwanted. In a moment of public vulnerability, Horley confesses his queerness and recounts a scandalous past relationship with a now-deceased uncle, effectively shattering his reputation but also freeing himself from the burden of secrecy.

Belle and Horley flee to an inn called the Cheese and Anchor, where Bonny and his lover Valentine await. The inn is as chaotic as the escape, with eccentric guests and emotional minefields, but the time spent there becomes a crucible for Belle and Horley’s evolving bond.

Belle continues to offer him something deeper than acceptance—she offers him companionship without conditions. Despite his belief that he is undeserving, Horley begins to consider that perhaps their marriage, however unorthodox, could be a foundation for something real.

The story explores the space between love and friendship. Valentine and Bonny, open and unabashed in their affections, serve as both inspiration and counterpoint to Belle and Horley’s more ambiguous connection.

Their presence highlights the kinds of freedom Belle and Horley long for but feel unable to claim. Belle, constantly caught between defiance and yearning, struggles with her limited role in the lives of those around her.

Horley, crushed under the weight of guilt, performs self-loathing as if it were duty. Yet through shared jokes, late-night talks, and small gestures of care, their relationship deepens.

The narrative then pivots to another emotional high point: Belle and Verity Carswile, Horley’s former fiancée, share an unexpectedly tender moment. When Belle finds Verity distraught, the two women engage in a reflective conversation about morality, pain, and self-worth.

Their talk shifts into emotional intimacy, culminating in a scene beneath a willow tree where they share affection, vulnerability, and eventually physical intimacy. Belle, often unsure of her capacity to love, begins to find clarity in Verity’s quiet understanding.

Verity, in turn, experiences what it means to be desired and seen for who she is. This connection reframes Belle’s view of herself, challenging her assumption that she is incapable of romantic feeling.

Meanwhile, Horley, now known more frequently by his given name Rufus, faces his own emotional turning point. He comes to value Belle as a partner and friend, even as he acknowledges she cannot and should not be his only emotional anchor.

Their marriage, conducted quickly at Gretna Green, is a symbol of mutual trust rather than romantic triumph. Belle, recognizing that Rufus still longs for emotional intimacy with a man, gives him the space to pursue a relationship with Gil—Bonny’s friend and a man who helps Rufus rediscover desire without shame.

Gil and Rufus’s connection is rendered with humor and care. They playfully reimagine a romantic fantasy, with Gil performing the role of a roguish highwayman.

Their encounter, while sensual, is also about emotional truth—both men grappling with the scars left by rejection and repression. The intimacy they find is as much about honesty as it is about pleasure.

As these emotional threads converge, the story takes Belle and Rufus to Florence. They are invited to a musical performance by Orfeo, a famous singer whose presence stirs something profound in Belle.

At the event, she is pulled into a bizarre conversation with Lady Farrow about a proposed sexual threesome. Belle navigates it with comic finesse, while secretly arranging a surprise for Rufus: she has tracked down his estranged parents and arranged a meeting.

The aftermath is turbulent. Belle is injured while defending Orfeo from an assault by a deranged patron, and the emotional intensity of that event forces everyone to re-evaluate what matters.

Belle accompanies Orfeo to safety, spending a quiet evening with them and Peggy, Orfeo’s loyal friend. Watching their life together—unremarkable, domestic, and rooted in care—gives Belle a glimpse of the kind of future she may want for herself.

A turning point occurs when Belle, caring for Peggy’s baby, begins to imagine a life that includes family, permanence, and mutual effort. She realizes that her marriage with Rufus may hold more potential than she once allowed herself to believe.

Yet when Rufus confronts her about contacting his parents, she panics. Though the reunion between Rufus and his parents is moving and restorative, Belle believes she has robbed him of the romantic fairytale ending he might have had.

She writes him a letter and flees.

The climax sees Rufus chasing after her, catching her at the docks before she can board a ship. They argue, emotionally raw and exhausted, and ultimately affirm their bond—not because they have to, but because they want to.

Their relationship is not built on traditional love or fantasy, but on choice, effort, and acceptance. In a dramatic gesture, they leap from the boat together, symbolizing their renewed commitment.

Something Extraordinary closes on a note of intentional, imperfect joy. Belle and Rufus, neither of whom began the story believing themselves capable of or deserving love, have built something durable and deeply personal.

Their happiness is not idealized—it is chosen, messy, and hard-won. But it is theirs, and that makes it enough.

Characters

Arabella “Belle” Tarleton

Arabella “Belle” Tarleton is the resolute, emotionally intelligent heart of Something Extraordinary. From the outset, she defies the constraints of Victorian femininity by proposing a marriage not for love, wealth, or status, but as a mutual survival pact.

Her fierce independence is tempered by a profound empathy, particularly toward the wounded men around her. Belle’s complexity emerges in her confrontation with Horley, where she dismantles his self-deception and insists on the reality and worth of their connection.

Far from being merely a catalyst for Horley’s transformation, Belle undergoes her own journey—from feeling marginalized by her brother Bonny’s chosen family to forging a path toward emotional fulfillment and autonomy. Her developing relationship with Verity further reveals her capacity for vulnerability and deep, nontraditional love.

Belle is unafraid of messiness—emotional, social, or sexual—and her decisions are driven by a strong moral compass rooted in compassion rather than convention. Her moment of clarity with baby Stella signifies a turning point: Belle realizes she desires stability and family, even if those don’t come in traditional forms.

Ultimately, Belle embodies a radical redefinition of love and commitment, choosing fierce loyalty and chosen family over societal expectations.

Sir Horley Comewithers (Rufus)

Sir Horley, often called Rufus, is a portrait of queer repression and emotional fatigue. Trapped between familial expectation, societal norms, and the scars of past heartbreaks, Horley seeks solace in alcohol and sardonic detachment.

At first glance, he appears incapable of affection or connection, dismissing his past closeness with Belle as performance. Yet it is precisely this performance that Belle interrogates, challenging him to confront his yearning to be seen and accepted.

Horley’s vulnerability is laid bare during their chaotic elopement and subsequent confessions, especially when he publicly acknowledges both his queerness and the shame inflicted by his family. His marriage to Belle, though not romantic in the conventional sense, becomes a pivotal act of reclamation.

Over time, Horley allows himself to hope again—not for grand passion, but for companionship, safety, and emotional truth. His budding relationship with Gil offers a humorous yet earnest exploration of desire, fantasy, and trust, further unraveling his emotional guardedness.

Rufus’s arc is not about perfection but progress—finding joy in intimacy, in found family, and ultimately in the choice to live honestly.

Verity Carswile

Verity Carswile begins as a seemingly pious, reserved fiancée but evolves into one of the most emotionally dynamic characters in the novel. Initially caught in the moral crossfire between Belle and Horley, she is revealed to be deeply introspective and quietly courageous.

Her emotional unraveling in the later chapters—triggered by her tangled history with Rufus—allows for a profound exchange with Belle, where faith, morality, and desire intersect. Verity’s kindness toward Belle, her willingness to see her not as broken but different, becomes the foundation for their romantic connection.

The sensuality and joy she displays during their night beneath the willow tree peel back layers of repression, revealing a woman capable of tenderness, humor, and longing. Verity’s relationship with Belle reframes both characters’ understandings of love, anchoring it in empathy, shared vulnerability, and nonjudgmental acceptance.

By the end, Verity stands as a figure of transformation—not through abandonment of faith, but through its reframing as inclusive and compassionate.

Bonny Tarleton

Bonny, Belle’s twin brother, serves as both a foil and a mirror to her. While he has found a form of liberation and happiness in his relationship with Valentine, he remains somewhat oblivious to the emotional gaps in Belle’s life.

His presence underscores the book’s exploration of chosen family—he has found his, and Belle must find hers. Bonny is affectionate and well-meaning but unintentionally neglectful, highlighting the quiet isolation Belle feels.

Despite this, his existence within the narrative is vital: he represents what’s possible for queer people in this world—happiness, stability, and love—while also reminding Belle of what she lacks and must create on her own terms.

Valentine

Valentine, Bonny’s lover, is both comic relief and emotional ballast. Eccentric and unfiltered, he nonetheless has moments of deep insight, especially concerning relationships and desire.

His presence adds texture to the narrative’s theme of unapologetic queerness, showing a model of love and flamboyance that is not merely tolerated but celebrated. Valentine’s ease with his identity contrasts sharply with Horley’s torment, serving as an aspirational figure, if also an occasionally exasperating one.

His love for Bonny is unshakable, and his bond with Belle—though not deeply explored—carries a subtle warmth.

Gil

Gil, the object of Rufus’s affection, is introduced with theatrical flair and gleeful deviance. His fantasy of being a highwayman and his delight in consensual power dynamics provide not only levity but also a safe space for Rufus to explore vulnerability.

Gil’s willingness to play, to meet Rufus on his own emotional terms, reveals an understanding far deeper than initial impressions suggest. He represents a romantic ideal that is free from shame, one rooted in mutual respect, consent, and joy.

His presence is essential in allowing Rufus to imagine a future where he is not merely surviving but thriving.

Orfeo

Orfeo, the celebrated singer, is initially positioned as an otherworldly figure—beautiful, remote, and enigmatic. Yet beneath the fame lies a person tired of performance, seeking refuge and sincerity.

Their interactions with Belle move from guarded to intimate, with Orfeo slowly revealing a desire for connection beyond admiration. Orfeo’s trauma, especially the violent encounter with their former patron, brings into focus the fragility behind the glamour.

Their friendship with Peggy, and the way they lean into her steadfastness, show that even the most glittering among us need grounding. Orfeo’s apology to Belle signals growth—a willingness to be seen not as a symbol, but as a person.

Peggy

Peggy is a figure of chaotic energy, warmth, and irreverence. A sharp-tongued friend to Belle and partner to Orfeo, she provides comic relief while also anchoring many of the story’s most emotionally raw moments.

Her teasing pushes Belle to confront her own emotional hesitations, and her nurturing (particularly of baby Stella) shows a quieter, steadfast kind of love. Peggy’s role as a mother and caregiver broadens the novel’s conception of family, emphasizing that love can manifest in countless, nontraditional ways.

Her domestic space, shared with Orfeo and Stella, becomes a haven not just for characters but for the narrative’s core themes of acceptance and chosen intimacy.

Lady Farrow

Lady Farrow is the embodiment of aristocratic absurdity. Her inappropriate proposition for a sexual threesome, though outrageous, underscores the way privilege often masks perverse desperation.

While her role is mostly comic, she serves as a sharp contrast to characters like Belle and Rufus, who are trying—against all odds—to live honestly and with emotional integrity. Lady Farrow reminds us that social respectability often hides deep dysfunction, and that honesty, however messy, is more admirable than artifice.

Æthelflæd (the Pig)

Though comical, Æthelflæd the pig adds a layer of domestic grounding to the narrative. Her presence symbolizes the unorthodox life Belle and Rufus are building—a home filled with absurdity, care, and imperfection.

She becomes a recurring motif for the odd sort of happiness they are forging together: one that includes livestock, laughter, and the daily, unspectacular work of choosing to stay.

Themes

Queer Identity and the Burden of Shame

In Something Extraordinary, the portrayal of queer identity is starkly honest and emotionally intricate, focusing especially on the lifelong scars left by societal and familial rejection. Sir Horley embodies a man fragmented by internalized homophobia and emotional repression, shaped by a lifetime of being told that his desires are shameful, dangerous, or obscene.

His queerness is not just a matter of romantic preference—it is a fundamental source of both his alienation and his desire for belonging. His relationship with Belle’s brother Bonny, which ended in unrequited longing, further compounds his sense of inadequacy and despair.

The fact that his queer identity is treated not as a side plot but as the very thing that defines his trajectory speaks to the book’s uncompromising stance on the personal costs of being marginalized.

Horley’s confession about his love for his uncle and the public shaming he experiences underscore how societal expectations dehumanize queer individuals, reducing their complex emotional lives to scandal or pathology. Even within his own family, he is viewed as a stain, an unwanted disruption of decorum.

Belle, in contrast, does not merely tolerate Horley’s identity; she fights to affirm it, refusing to let him retreat into self-loathing. Through Belle’s relentless insistence on his worth, the narrative champions a kind of queer salvation—not through romance, but through being seen and accepted without conditions.

This theme carries through to other characters as well, especially Valentine and Bonny, whose open and affectionate partnership acts as a counterpoint to Horley’s suppressed desires. Their freedom makes visible what Horley has long believed impossible: a life where queerness is not just bearable, but beautiful.

Chosen Family and Unconventional Bonds

The emotional heart of Something Extraordinary is not romantic love in the traditional sense but the formation of chosen families and the power of emotional alliances forged in adversity. Belle and Horley’s relationship challenges conventional narratives of marriage and intimacy.

Their union, proposed by Belle in a moment of defiant hope, is not about passion or societal advancement but about mutual care and survival. It’s a radical commitment between two misfits who recognize each other’s brokenness and still choose to stay.

Their bond is a quiet rebellion against the notion that love must fit within heteronormative ideals or romantic fantasies to be valid or worthy.

Belle’s growing relationship with Verity further complicates the web of emotional loyalty. What begins as ideological opposition transforms into a tender, romantic attachment built on vulnerability and shared understanding.

Similarly, Rufus and Gil’s connection—borne out of theatrical roleplay and genuine desire—serves as a reminder that love can bloom in unexpected ways when people feel safe enough to be themselves. Throughout the story, the characters form constellations of trust, interdependence, and acceptance that defy traditional categories of family or romantic pairings.

These bonds are not always tidy or permanent, but they are deeply meaningful, offering a version of fulfillment rooted in choice rather than obligation. The novel insists that people can build lives together not because they must, but because they wish to—an act of willful, powerful love in a world that often denies them that freedom.

The Search for Worth and the Fear of Inadequacy

Running beneath every interaction in Something Extraordinary is a shared fear among its characters: the haunting belief that they are not enough. Belle feels this acutely in her relationships with others, particularly her brother Bonny and his partner Valentine, where she constantly questions her place in a world that seems to value romance and traditional femininity above all else.

She is witty, resilient, and deeply perceptive, but none of these qualities seem to count in a society where a woman’s worth is often judged by her desirability or obedience. Her decision to marry Horley, despite knowing that love is absent or undefined, is her way of creating her own worth—a refusal to be left behind or diminished.

Horley’s inferiority complex is more explicitly tied to his past and sexuality. Years of being belittled, misunderstood, and punished for who he is have left him with a deeply ingrained belief that he is fundamentally unlovable.

Every attempt Belle makes to reach him is met first with suspicion, then sarcasm, and finally quiet desperation. He cannot fathom that anyone might truly care for him without conditions.

This internal conflict is not resolved quickly or neatly. Instead, the narrative tracks the slow erosion of his defenses through consistent acts of kindness, loyalty, and empathy from those around him.

His eventual ability to reconcile with his estranged parents, and his decision to leap back into a life with Belle, mark a tentative but profound step toward self-acceptance.

The fear of not being enough is echoed in characters like Verity, who wrestles with the idea that her rigid faith might be a mask for loneliness, and in Rufus, who only begins to explore his own capacity for love when Belle gifts him the freedom to do so. The novel gives space to these insecurities, not as weaknesses to be vanquished but as truths to be understood.

By exploring how characters redefine their own value outside of societal judgments, the story becomes a meditation on dignity, courage, and the quiet miracle of being chosen—even when one feels unworthy.

Agency, Rebellion, and Rewriting Destiny

Throughout Something Extraordinary, characters consistently resist the roles society has assigned them, choosing instead to write their own stories—no matter how absurd, complicated, or messy those stories might be. Belle, in particular, stands as a figure of spirited defiance.

Her impulsive elopement with Horley, her later pursuit of Verity, and her unorthodox approach to marriage all demonstrate a refusal to be constrained by the scripts that women are expected to follow. She is not waiting to be rescued or validated by a romantic partner; she is seeking a life that feels true to her own sense of justice and loyalty, even if it looks nothing like the lives of others.

Horley’s arc is a quieter rebellion. At the beginning, he is resigned to a life of bitter compliance, agreeing to a marriage he does not want in order to maintain a veneer of respectability.

But through Belle’s intervention and the increasing visibility of his own desires, he begins to question the inevitability of that path. His eventual public admission of queerness and rejection of his aunt’s authority is a radical act of personal liberation.

In reclaiming his agency, he does not suddenly become confident or healed—but he does become honest, and in that honesty lies freedom.

The novel does not suggest that rebellion always results in neat resolution. The elopement is chaotic, the relationships ambiguous, the endings untraditional.

But that is precisely the point: real agency is not about escaping all consequences or achieving an ideal; it is about making deliberate choices in the face of constraint. The characters do not wait for permission to change their lives—they seize it, even if doing so means jumping off a boat with no guarantee of what comes next.

Their courage to leap, to defy, and to define themselves on their own terms forms the narrative’s moral backbone.

Love Beyond Romance

While Something Extraordinary includes moments of romantic intensity—particularly between Belle and Verity, and Rufus and Gil—it resists the notion that romantic love is the ultimate form of fulfillment. Belle and Horley’s relationship is the clearest example of this.

Their marriage is not founded on love, nor is it meant to transform into a conventional romance. Instead, it offers something perhaps even rarer: steadfastness, loyalty, and the willingness to share a life with another flawed, frightened, and fundamentally decent person.

They do not need to call it love to make it real.

This theme is reflected in the various configurations of care throughout the novel. Belle’s affection for her brother, her respect for Peggy, her protectiveness of Orfeo, and even her awkward tenderness with baby Stella all represent different ways of loving that are no less powerful for being non-romantic.

The same is true for Rufus, whose friendship with Belle, playful camaraderie with Gil, and emotional reconciliation with his parents form a patchwork of support that affirms his belonging in the world.

By broadening the definition of what it means to love and be loved, the novel honors forms of connection that are often overlooked or undervalued. It suggests that emotional fulfillment doesn’t have to look like candlelit dinners or whispered declarations—it can look like shared silence, mutual effort, or even comedic disaster.

In doing so, it dignifies the lives of those who may never find fairy-tale romance but who still live fully, generously, and with tremendous heart.