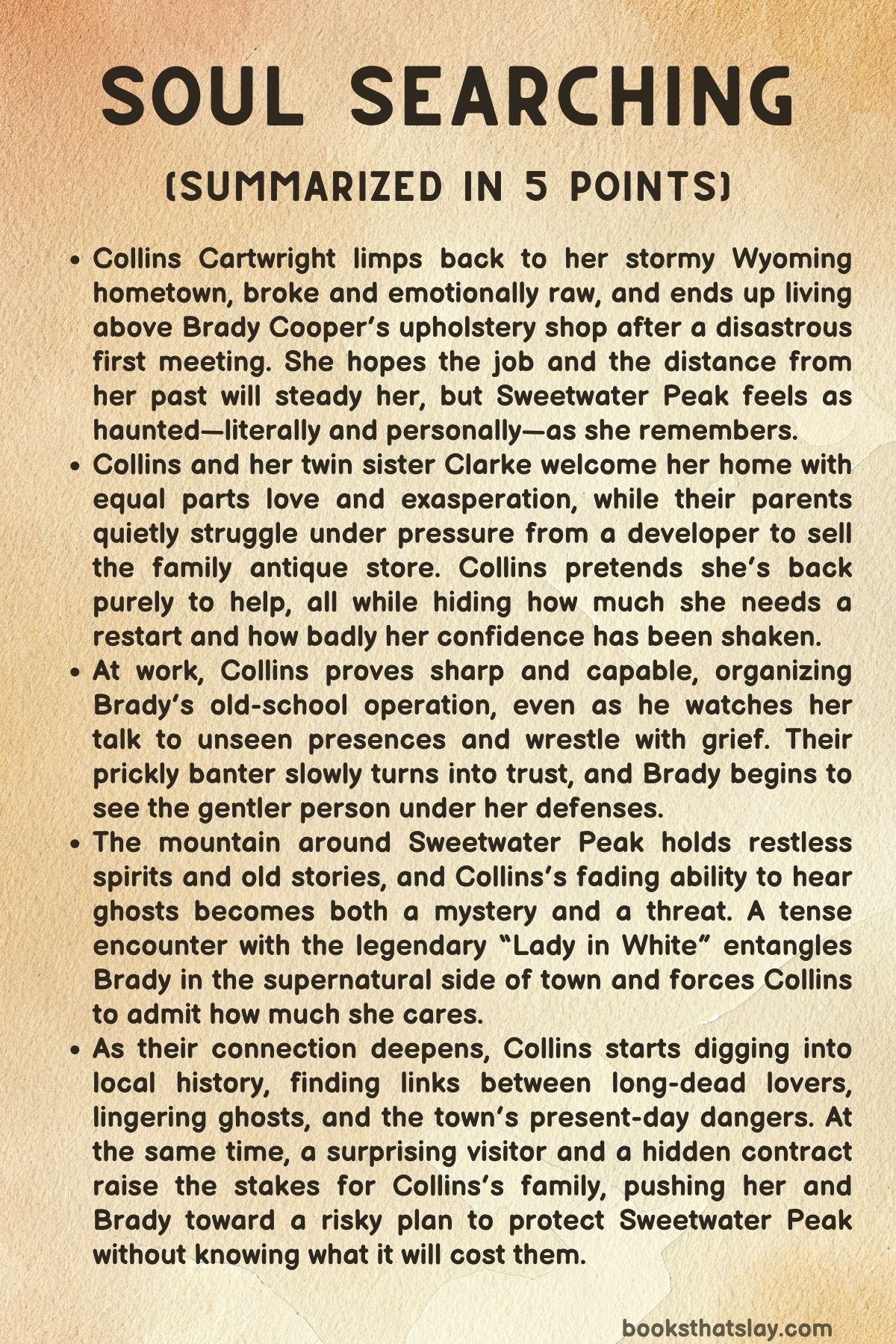

Soul Searching Summary, Characters and Themes

Soul Searching by Lyla Sage is a small-town paranormal romance set in the high country of Wyoming. It follows Collins Cartwright, a photographer who’s run from her haunted hometown for years, and Brady Cooper, an ex-software engineer who rebuilt his life as an upholsterer.

When Collins comes home broke, grieving, and unsure of her fading ability to hear ghosts, she lands in Brady’s apartment above his shop. Their unexpected closeness grows alongside a deepening mystery in Sweetwater Peak—one tied to restless spirits, family history, and a ruthless developer threatening the town’s heart.

Summary

Collins Cartwright returns to Sweetwater Peak after years away, driving her battered 2002 Camry up a remote Wyoming road under storm clouds. The car overheats and dies in a cell-service dead zone, leaving her stranded on a cliffside shoulder in pouring rain.

She prepares to spend the night alone until someone approaches the window. Panicking, she unloads pepper spray—only to discover she’s attacked Brady Cooper, the quiet upholsterer who offered her a temporary job and a room above his shop.

Her twin sister, Clarke, arrives right behind him, furious and relieved. Collins helps rinse Brady’s eyes, mortified, while Clarke drags them back to town in Brady’s pickup.

In the morning, Collins wakes on Clarke’s couch, uneasy about being home. She hasn’t had steady photography work since an unnamed incident that knocked her confidence flat, and her bank account is nearly empty.

She tells her parents she’s back to help at their antique store, Toades, but privately she needs a lifeline and is willing to let them believe whatever makes this return easier. Sweetwater Peak is also the one place where ghosts never stop hovering.

Collins and Clarke grew up seeing and hearing spirits, a family trait their mother Joanie calls “sensitivity. ” Coming back means walking again through a town full of the dead—and the memories they drag behind them.

Collins starts work at Coop’s Upholstery the same day. The shop is old-fashioned but warm, filled with leather, fabric, and half-restored pieces from Toades.

Brady is polite, dryly funny, and still blinking through the afterburn of her pepper spray. He gives her a tour and explains her tasks.

Collins immediately modernizes his chaos: organizing supplies, cleaning the storefront, setting up an email account, and building a project tracker. Brady can’t decide if her nonstop talking is irritating or impressive.

He’s an outsider in town, someone who clearly came to disappear into work, and he dodges personal questions with the same practiced calm he uses to stitch seams straight.

Living above the shop brings its own tension. Collins has her own apartment across the hall, with shared kitchen and living space between them.

The building is thick with spirits—she can see them darting in corners and lingering by doorways—but something is wrong. For months her ability to hear ghosts has gone silent, and now the dead hover around her without speaking.

A blurry female spirit appears often, vanishing whenever Collins confronts her. Other ghosts keep nudging her packed camera bag as if trying to remind her who she used to be.

The quiet in her head is lonelier than any noise she ever feared.

After a family dinner at Toades, Collins walks back to the apartment in an unseasonably warm night that feels too empty. She sits on the steps behind the building and cries, shaken by how little coming home has healed her grief.

Brady steps outside to take out trash and finds her there. He offers help, but she snaps that she wants to be alone.

He backs off without complaint, yet the image of her hunched in the dark sticks with him.

Days pass in a messy rhythm of work, banter, and ghosts that won’t talk. Brady asks Collins to help deliver reupholstered chairs to Ms. Papadakis, a wealthy local with long-running drama with the Cartwrights. The drive becomes a tug-of-war between flirtation and friction, Collins teasing him as “boring Brady” for refusing risky shortcuts, Brady quietly refusing to rise to the bait.

She admits she talks to herself because her thoughts never stop, and he recognizes the restless edge under her sarcasm.

Back at the shop, a jar of sharp tacks slides off a shelf behind Brady as if pushed by an unseen hand. Collins yanks him out of the way just before it crashes and shatters.

He’s shaken. She pretends it was an uneven shelf, but she knows better.

Worried about leaving him alone in the building, she invites him to a childhood hiding place: an abandoned mountain church.

They drive up at dusk with lanterns, candles, and a joint. Inside the ruin, the roof opens to a sky full of stars.

As they smoke and talk, Collins shares local history: an early settlement destroyed by an earthquake that cracked the mountain and changed the river. Their conversation turns personal.

Brady admits he moved to Sweetwater Peak for a fresh start after ending a seven-year engagement. Collins, feeling braver in the candlelight, tells him her truth—she always heard ghosts, and then the voices stopped, leaving her cut off and afraid she’s lost herself.

While she paces, a voice suddenly breaks the silence of her mind. She freezes, listening.

The floor collapses beneath her. Brady lunges and hauls her back to safety.

Shaking, she says she heard a ghost again—the first time in months.

Unable to sleep after that, Collins drives at dawn to Boone Ryder’s ranch, a gruff older family friend who treats her like a stubborn niece. He works her hard moving cattle and scolds her for disappearing into the mountains without telling anyone.

His blunt care anchors her, and his warning lands: she doesn’t get to vanish anymore, not while people are waiting.

Soon after, Collins takes Brady hiking to a secret river viewpoint. She explains the mountain’s spirits “anchor” to places and warns him about one legend in particular: the Lady in White, a woman who died waiting in these woods for her lover.

The trail grows tense, wind snapping through trees like whispered threats. At the clearing, Collins sees the Lady in White behind Brady—gauzy, intent, possessive.

Brady can’t see her, but he feels her icy touch, a pain that pins his legs. Collins speaks directly to the ghost, insisting Brady isn’t the man she’s waiting for.

In a rush of panic and protectiveness, Collins blurts that Brady is hers. The spirit hesitates, murmurs that he looks like her lost love, then releases him and disappears.

Brady is rattled into belief, and Collins is rattled by what she said out loud.

Their closeness accelerates. They share breakfasts in the dim kitchen, long talks during storms, and a growing honesty about the lives they had before Sweetwater Peak.

Brady admits his old relationship felt like control wrapped in convenience. Collins admits she’s been avoiding her camera because photography feels tied to who she was before everything broke.

Candlelit board-game nights turn into kisses, and kisses turn into a night together that leaves them both aching and surprised by how right it feels.

Collins later brings Brady to a hidden cellar in the woods that once belonged to Emily Hofstadt, the town’s long-time postmistress. Emily had entrusted Collins with Sweetwater Peak’s private archive: boxes of newspapers, ledgers, and artifacts dating back decades, connected to the post office by a winter tunnel.

Collins searches for the obituary of Earnest, a ghost friend who died in the 1950s in a mysterious crash on his way to meet someone by the river. The obituary doesn’t name the other driver, but another nearby notice catches her eye: Adeline Bennett, a young woman who froze to death near the river.

Collins realizes Adeline is the Lady in White, and that Adeline was Earnest’s lover. The haunting on the mountain isn’t random—it’s a love left unfinished.

In the cellar, Brady finds an old Blue Sky Geographic magazine featuring Sweetwater Peak. He recognizes the photos that inspired him years ago to visit this place.

The photographer’s name stuns him: Collins Cartwright. Her work shaped his life before they ever met.

Collins admits she hasn’t known how to be proud of that part of herself lately. Brady tells her plainly that her art mattered, and that he loves her.

She says it back, trembling like she means it.

Their new happiness crashes into town politics. At the taffy shop, they run into Jackie—Brady’s wealthy ex—who is in Sweetwater Peak on business for her father, developer Ed Sullivan.

Jackie reveals a signed contract for three Cartwright properties, including Toades. Collins is blindsided; her parents had been pressured to sell but she thought they were holding out.

Jackie, nervous and regretful, quietly gives Brady a copy of the contract and promises to stall her father.

At Toades, the family erupts. Joanie explains she believed she signed something reversible, tempted by a huge payout because storms have wrecked their basement and repairs are costly.

Clarke feels betrayed and furious. Brady calls Boone for backup, and Boone loops in Cam Tucker, a real-estate lawyer, by FaceTime.

Cam confirms the contract is binding. His only immediate way to freeze the sale is brutal: Joanie and Dex must file for divorce so their assets are locked in court while they gather evidence for a lawsuit.

The plan is messy and painful, but it buys time.

That night, Collins and Clarke retreat to their childhood ritual for summoning the Lady in White. Under a sheet and half-laughing through tears, they trade secrets.

Collins admits she came home broke and scared because her ghost-hearing vanished. Clarke admits she’s been talking with Wilder Wilkes’s ghost about his son, Leith.

The ritual works. Adeline appears, and Earnest arrives when he hears her name.

Across decades of loss, they find each other again. Their hands meet, and Adeline smiles as if the mountain finally exhales.

With the town’s spirits settling and the sale delayed, Collins decides Sweetwater Peak needs more than luck. She learns Sullivan has targeted other rural towns she once photographed.

She and Brady commit to traveling together to gather testimonies, contracts, and proof for Cam’s case. Months later they are on the road, partners in love and purpose, while Sweetwater Peak repairs Toades and braces for the fight ahead.

Collins’s abilities return stronger, her camera no longer a burden but a tool again. As they drive toward the next town, a ghost named Elda wakes Collins with urgency to meet Cam, and Collins notices in a recent photo that Clarke seems to be wearing an engagement ring—hinting that healing in Sweetwater Peak is still unfolding, in both the living and the dead.

Characters

Collins Cartwright

Collins is the emotional and narrative center of Soul Searching. She returns to Sweetwater Peak carrying a messy stack of motivations she barely admits to herself: financial desperation after a photography “incident” derailed her career, grief that hasn’t softened with distance, and a complicated love–resentment bond with her family and hometown.

Her personality runs on sharp edges and restless energy—quick to defend herself with sarcasm, quicker to lash out when she feels cornered, and habitually armed (pepper spray first, questions later). Yet under that armor she’s deeply tender, especially toward her sister and parents, and her protective instincts are almost involuntary, as shown when she saves Brady from the falling tacks jar and later risks emotional exposure to help both him and the town.

The supernatural thread in her character is not just a quirky trait; her ability to see and hear ghosts is tied to her identity and sense of purpose. When the voices go silent, it’s like losing a limb, intensifying her loneliness and creative paralysis.

Her arc is a slow re-integration: she relearns trust, accepts love without running, and reconnects with her own talent by choosing to fight for Sweetwater Peak and resurrecting her photography as a tool for justice rather than escape.

Brady Cooper

Brady arrives in Sweetwater Peak as an outsider who wants quiet, structure, and a clean reset. He presents as steady to the point of seeming boring—orderly shop routines, analog filing systems, emotional self-control—but that steadiness is revealed as hard-won, shaped by early family fracture and years of managing other people’s feelings.

The move from software engineering to upholstery mirrors his internal shift: away from abstract ambition and toward tangible craft, patience, and repair. Brady’s decency is consistent rather than dramatic; he helps Collins before really knowing her, shares his home, and stays present even when her moods swing sharp.

What’s compelling about him is how he balances caution with courage. He’s wary of Collins at first, yet he chooses to lean in—following her into haunted spaces, believing her when a ghost harms him, and later committing to a risky road trip to protect her family.

His romance with Collins grows out of mutual recognition: he sees the artist in her even when she can’t, and she sees the softness beneath his self-imposed restraint. By the time he says he loves her, it feels like an act of rebuilding a life he wants rather than settling for one that’s convenient.

Clarke Cartwright

Clarke is Collins’s twin and her main tether to home—part sister, part mirror, part moral compass. She has a grounded, competent warmth that shows up in small daily acts: making breakfast, lending clothes, arranging housing and work, and stepping in as the practical translator between Collins’s volatility and the family’s needs.

She also has a sharp spine; she calls Collins out when she’s reckless or avoidant and refuses to sugarcoat the consequences. Clarke’s relationship with the supernatural is more quietly integrated than Collins’s.

She accepts ghosts as part of life but doesn’t romanticize them, and her private conversations with Wilder Wilkes’s ghost suggest a compassion that extends beyond the living. Her anger at the contract betrayal comes from love and loyalty to the town, not cruelty toward her parents.

By the end, her hinted engagement ring suggests her own life is expanding, but she still remains deeply entwined with Collins, showing that their twin bond is not about dependency so much as shared history and unspoken understanding.

Dex Cartwright

Dex is the family’s steady backbone: a practical, outdoors-trained father who fixes leaks, tries to tow broken cars with optimism, and teaches survival skills that become part of Collins’s identity. His role is quiet but crucial because he embodies stability without emotional distance.

He mediates twin arguments, tries to keep the family together under pressure, and carries the everyday burdens of keeping Toades afloat. Dex’s love expresses itself through action rather than talk, and that makes him a grounding presence in a story full of storms—literal and interpersonal.

The proposed fake divorce is a gut-punch to his character because it forces him to weaponize the institution he’s used to protect his family, showing how deeply he’ll bend for them even when it hurts. He’s not portrayed as flawless, but as a man trying to hold a home together while the world keeps prying at its foundations.

Joanie Cartwright

Joanie is the emotional hearth of the Cartwright family and also a living bridge to the book’s supernatural atmosphere. Her sensitivity to energy in objects places her in the same intuitive lineage as her daughters, but her gift feels maternal rather than exploratory: she senses the weight of places and wants to care for them.

Joanie’s warmth is evident in how she welcomes Collins without interrogation and in the way she keeps feeding people even while her basement floods. At the same time, she’s vulnerable to fear and exhaustion, which makes her susceptible to Ed Sullivan’s offer.

The precontract mistake isn’t stupidity; it’s a portrait of a woman cornered by financial stress and the slow erosion of security. Her willingness to sign, then to consider a fake divorce to undo it, shows a painful mix of desperation and devotion.

Joanie represents the theme of home as both sanctuary and trap—she loves Sweetwater Peak fiercely, but she also wants survival for her family, and those desires collide.

Boone Ryder

Boone is the gruff, affectionate sentinel of the mountain world around Sweetwater Peak. He’s drawn in broad strokes—insults as greetings, work as therapy, love expressed through blunt warnings—but he’s emotionally perceptive in a way that surprises both Collins and the reader.

When Collins shows up at dawn, he doesn’t coddle her; he puts her on a horse, makes her move cattle, and lets physical effort burn through her spiraling thoughts. Boone functions as a moral elder and a reminder of the town’s older values: responsibility, honesty, and respect for forces bigger than yourself, whether that’s wilderness or grief.

His urging to reconcile with Clarke shows he sees the family as a living ecosystem that has to be tended before it fractures. In a story about ghosts and memory, Boone is a kind of living anchor—stubbornly present, insisting the living still have work to do.

Earnest

Earnest is a longstanding ghost companion to the Cartwright women, and his absence early on is a symbol of Collins’s disconnection from herself. He represents the gentler side of the supernatural: a familiar, almost familial spirit whose relationship with Collins goes beyond spookiness into friendship and shared history.

His death—run off the road on the way to meet someone he loved—casts him as a figure of unfinished longing, which aligns him thematically with Collins’s own unfinished grief. When he finally reunites with Adeline, his role shifts from lingering sorrow to closure, reinforcing the book’s idea that healing is possible not only for the living but also for the dead who are tethered by love and regret.

Adeline Bennett / The Lady in White

Adeline is the legendary haunting of Sweetwater Peak, first presented as a chilling local myth and then revealed as a deeply human tragedy. As the Lady in White, she’s frightening—possessive, cold enough to paralyze Brady, and fueled by a decades-long fixation on the lover she lost.

But once her backstory surfaces through the cellar obituaries, her terror clarifies into grief. Her waiting by the river until she froze to death reframes her as a woman trapped by betrayal and time, mirroring the town’s own frozen vulnerability under Sullivan’s plans.

Adeline’s interaction with Collins is key: she responds to direct confrontation and to truth, backing away when Collins claims Brady as her own, suggesting that what she wants isn’t harm but recognition and reunion. Her eventual meeting with Earnest resolves a communal wound, turning her from predator-ghost into a figure of earned peace.

Jackie

Jackie is Brady’s wealthy ex-fiancée, and she arrives like a storm cloud with a surprisingly human core. She could have been written as a simple antagonist, but instead she’s conflicted—still tethered to her father’s ambitions yet uneasy about their impact.

Her decision to hand Brady the contract and promise to stall her father’s project reveals a conscience that’s stronger than her loyalty to power. Jackie’s presence also tests Brady and Collins as a couple, forcing Brady to articulate why leaving that engagement was right and pushing Collins to face the reality that personal history and civic danger are intertwined.

She embodies the theme of complicity: she’s part of the machinery threatening Sweetwater Peak, but she chooses to jam the gears when it counts.

Ed Sullivan

Ed Sullivan is the clearest human antagonist, a developer who treats rural towns like chips to cash in. He’s less a complex interior character than a force of pressure—relentless, polished, and confident that money will eventually unlock any door.

His targeting of multiple towns Collins photographed suggests predatory strategy rather than coincidence, making him a symbol of extractive modernity: progress that erases place, memory, and community. The story uses him to sharpen the stakes for Collins’s return to photography, turning her art into an instrument to fight back against the kind of person who reduces history to real estate.

Cam Tucker

Cam appears briefly but plays an outsized structural role as the real-estate lawyer who offers the family a desperate legal lifeline. He reads as sharp, pragmatic, and unflinching—someone who understands the rules of games like Sullivan’s and is willing to suggest morally strange tactics, like a strategic divorce, to protect clients.

Cam functions as the bridge between local heartbreak and formal resistance. His presence also validates Collins’s eventual mission: gathering evidence isn’t just emotional revenge, it’s a path with legal teeth.

Emily Hofstadt

Emily Hofstadt, though not present in the current timeline, is a quiet architect of Sweetwater Peak’s memory. As the long-time postmistress who built and preserved the secret cellar archive, she represents stewardship, foresight, and faith in continuity.

By choosing Collins as the inheritor of that history, Emily becomes part of Collins’s identity as a documentarian of place. Her hidden tunnel and painstaking preservation suggest a person who understood that survival in harsh landscapes requires both practical ingenuity and reverence for story.

Ms. Papadakis

Ms. Papadakis is a small but vivid figure who helps paint the town’s social texture.

Through Collins’s teasing stories about her wealth, family history, and childhood grudges, Ms. Papadakis becomes a symbol of long memory and community entanglement—someone whose presence reminds Brady that Sweetwater Peak runs on layered relationships and old narratives.

She’s also a narrative device to push Brady and Collins into partnership outside the shop, letting their banter and mutual dependence deepen.

Wilder Wilkes (ghost) and Leith

Wilder Wilkes’s ghost is part of the story’s widening supernatural web. Clarke’s conversations with him about his son Leith show that ghosts in this world aren’t all omens or threats; they’re retained relationships and unfinished responsibilities.

Wilder’s concern for Leith adds a generational angle to the haunting, hinting that Sweetwater Peak’s dead are still invested in the futures of the living. Leith, though offstage, becomes a person shaped by legacy and loss, suggesting room for further story beyond the current arc.

Elda

Elda appears late as a ghost who wakes Collins with urgency, signaling how fully Collins’s abilities have returned and how integrated they are becoming in her daily life. Elda feels like a messenger spirit, one of the practical dead who participate in ongoing community survival rather than merely haunting it.

Her presence underscores the shift from Collins’s earlier silence and isolation to a renewed role where listening to spirits is again a source of direction and purpose.

Themes

Homecoming, Belonging, and the Weight of Place

Collins’s return to Sweetwater Peak is not a simple change of scenery; it works like a confrontation with a landscape that knows her too well. From the moment her car fails on the isolated Wyoming road, the town is framed as both sanctuary and trap.

She comes back carrying practical desperation—no money, no work, a bruised professional history—but also emotional hesitation. She has trained herself to believe that distance is the only way to keep her family, her memories, and her own sensitivity to the supernatural manageable.

Coming home therefore isn’t nostalgic; it is destabilizing. The physical geography mirrors that tension.

Steep roads, dead zones without cell service, storms rolling over familiar ridges, and an old building buzzing with spirits all insist that place here is active, not neutral. Sweetwater Peak presses on Collins’s nerves and identity in a way that the outside world has not.

The novel uses the town to show how belonging can be complicated by history. Collins knows every back road and hiding spot, yet she feels hollow walking them again.

Her knowledge gives her power—she guides Brady through local lore, keeps him safe on the mountain, and later uses town archives to unlock buried truths—but it also anchors her to grief she hasn’t metabolized. Even ordinary spaces like the steps behind the apartment or the family dinner table become loaded with what she used to be and what she fears she cannot be again.

Brady’s outsider perspective intensifies this theme. He arrives seeking a reset, trying to build a new version of a life, while Collins arrives to face an old one.

Their contrasting relationships to Sweetwater Peak show two sides of belonging: how a place can rescue you by offering a fresh role, and how it can suffocate you by refusing to let former selves die quietly.

By the end, Sweetwater Peak becomes less a cage and more a base for renewal. Collins doesn’t “escape” her hometown; she re-claims it in a more honest way.

The town’s ghosts, its storms, its stubborn community, and even its economic threats force her to stop performing a detached version of herself. Instead, she learns to stand inside the mess of home without dissolving into it.

In Soul Searching, belonging is not portrayed as comfort; it is a negotiation between love for place and the pain embedded in it, and Collins’s arc shows that the negotiation can end in agency rather than retreat.

Grief, Absence, and the Slow Return of Voice

Loss is the quiet engine under almost every major choice Collins makes. Her break from Sweetwater Peak, the stalled photography career, the emptiness she feels in a warm silent night, and most sharply the disappearance of ghost voices from her life all point to grief that has never fully had language.

The voices stopping is more than a supernatural detail; it is a metaphor for how grief can cut someone off from their sense of connection. Collins has lived with spirits as companions, confidants, and proof that the past is still reachable.

When that channel goes silent, her world becomes lonelier in a specific way: not only has she lost people, she has lost the ability to feel them near. That’s why the town’s strange quiet unsettles her.

She is surrounded by presence she can see but not hear, which resembles mourning itself—knowing something meaningful is close, yet being unable to touch it.

Her grief is also tied to identity fracture. She avoids her camera bag as if it is an accusation.

She tells herself she returned for family help, but internally she knows she is running from failure and shame. The novel shows grief as layered: sorrow over what happened in her past “incident,” sorrow for the life she thought she would build through photography, and sorrow for the way her abilities once offered her certainty about love and afterlife.

These layers make her easily irritated, guarded, and tempted by isolation. When Brady finds her crying on the steps, her first survival instinct is to push him away.

She isn’t trying to be cruel; she is protecting a wound that she doesn’t trust anyone to see.

Healing doesn’t arrive through a single breakthrough. It comes in uneven pulses: a sudden ghost voice in the ruined church, a night of honest confession, a surprising tenderness after physical intimacy, and finally the reunion of Earnest and Adeline.

That reunion matters because it gives Collins a living example of grief resolving into peace. Reuniting the spirits is also her first clear act of purpose since returning.

She is no longer just enduring absence; she is shaping an ending. This act reframes her own losses.

If the dead can be guided toward closure, then her own unfinished sorrow might also have a path forward.

By the time her abilities return strongly, it feels earned rather than magical. The regained voice signals that she is re-opening herself to connection—with the town, with her craft, with love, and with her own history.

In Soul Searching, grief is not treated as a problem to solve but a landscape to walk through. Collins learns that silence can be temporary when someone allows themselves to be held by others and to pursue meaning again.

Love as Risk, Safety, and Mutual Seeing

The relationship between Collins and Brady grows from comic accident into emotional necessity, and the story tracks how love can be both destabilizing and grounding. Their first encounter—pepper spray, rain, fear, and embarrassment—establishes a pattern: Collins’s defenses fire instantly, while Brady chooses patience.

That mismatch is essential to the theme. Collins does not fall for him because he is flashy or dramatic; she falls because he is steady in ways her nervous system has stopped trusting.

Brady becomes a place where her guardedness can rest without being questioned into submission. Even when he is wary about living with her, he doesn’t try to control who she is.

He allows her to be strange, grieving, loud, and contradictory. That consent is what slowly makes her feel safer.

At the same time, love here is never presented as effortless safety. It is risk.

Collins risks being seen at her worst—crying on the steps, admitting her voices are gone, showing her burnout, confessing her attraction. Brady risks letting her into his history, including the breakup with Jackie and his own fear of not belonging.

Their flirting and banter allow them to test trust before naming it. When danger arrives through the Lady in White’s possession of Brady, Collins’s impulsive “he is mine” does not read as a dominance claim; it reads as a startled admission that her feelings are real enough to stake her heart in public.

Brady then has to decide whether to believe her world even when he cannot see it. His willingness to accept her perception confirms that love here includes faith in another person’s reality.

Their intimacy is treated as both physical and emotional repair. The sex scene is not a conquest or reward; it is an extension of tenderness they have been building through conversations, shared meals, and late-night honesty.

Afterwards they cling to softness because it is rare for both of them. For Collins, being held without expectation counteracts her instinct to disappear into solitude.

For Brady, being chosen directly counters the old relationship that felt like convenience and control. Love gives each of them a corrected experience of partnership.

Crucially, the romance also expands their courage toward the outside world. After the contract threat surfaces, Collins doesn’t retreat into private sadness.

She and Brady become a team, using her photography and his loyalty to gather evidence and protect her family. Their connection turns into shared direction.

In Soul Searching, love is not a rescue fantasy where one person fixes another. It is a mutual agreement to witness each other clearly, to accept risk, and to move forward side by side even when the road is haunted, uncertain, or both.

Family, Twinship, and the Push-Pull of Care

The Cartwright family dynamic shows how love can be deeply supportive while still feeling suffocating. Collins and Clarke’s twinship sits at the center of that tension.

Their banter is sharp and playful, but it also hides old fractures: Collins’s habit of vanishing without warning, Clarke’s resentment at being left to manage home pressures, and Collins’s private fear that she no longer fits inside the twin identity they once shared. The “twin code” jokes and sibling teasing are not filler; they show how families use humor to keep rupture from becoming explicit.

Underneath the jokes is a question of loyalty: what each sister owes the other when adulthood has pulled them into different shapes.

Parental relationships add another layer. Dex and Joanie are affectionate and proud, but they also carry expectations about who Collins should be in Sweetwater Peak.

Their insistence that she socialize, show Brady around, or settle into town life might come from care, yet to Collins it feels like pressure to perform recovery on command. She returns broke and fragile, and part of her survival strategy is to let her parents believe a simpler story.

That gap between what she says and what she feels reveals a family where love is present but direct vulnerability is hard. Joanie’s sensitivity to energy and the family’s shared gift with spirits create a bond that is unusual and intimate, yet even this bond cannot automatically protect Collins from feeling alone when her abilities fade.

She fears disappointing them not because they are cruel, but because they matter.

The looming sale of Toades Antiques intensifies the theme of family as both anchor and conflict site. Joanie signs a binding contract under financial stress, believing she is protecting the family’s future.

Clarke experiences it as betrayal and loss of heritage. Collins experiences it as another reminder that she left and therefore missed crucial moments.

None of them is purely right or wrong. The story treats family tension as a collision of fears: fear of poverty, fear of change, fear of being abandoned, fear of losing the past.

The desperate divorce tactic proposed by Cam is almost absurdly painful, yet it shows how far this family will go for each other when threatened.

What ultimately repairs the family is not a neat apology scene; it is shared action and renewed honesty. Collins’s confession about her missing powers and her financial state finally breaks the illusion that she can manage alone.

Clarke’s secret about talking with Wilder’s ghost exposes her own private burdens. Their willingness to place truth on the table restores the twin bond on more adult terms.

In Soul Searching, family love is shown as noisy, imperfect, and sometimes clumsy, but still worth choosing again. The Cartwrights don’t become conflict-free; they become more truthful, and that truth allows care to feel less like control and more like solidarity.

Memory, History, and the Living Presence of the Past

The ghosts in Sweetwater Peak are not treated as simple scares or quirky town flavor. They represent how the past remains active in people’s lives, shaping choices even when nobody speaks its name.

Collins’s lifelong ability to see and hear spirits means memory is not abstract for her. It is literal companionship, interruption, and sometimes threat.

When she returns to an apartment “swarming” with silent ghosts, she experiences a concentrated version of what memory can feel like: crowded, persistent, and demanding attention even when you are not ready. The spirits nudging her camera bag are a perfect example.

They are not just random hauntings; they act like unresolved history insisting she should not abandon who she once was. The supernatural therefore becomes a language for internal pressure.

The town archive hidden in Emily Hofstadt’s cellar brings this theme into focus. The cellar is an image of collective memory preserved against time—newspapers, ledgers, artifacts, secret tunnels built for survival.

Collins’s search for Earnest’s obituary is driven by friendship, but it becomes a recognition that personal grief connects to historical injustice. The missing truth about Earnest’s death is not only a private mystery; it reflects how towns bury uncomfortable stories, leaving spirits to wander without closure.

When Collins realizes Earnest and Adeline were lovers separated by violence and misfortune, she understands that history is not dead. It is waiting to be witnessed correctly.

This theme also connects to the modern threat posed by Ed Sullivan’s development project. The contract to buy Cartwright properties is an attempt to overwrite local memory with profit-driven redesign.

Jackie’s reveal that she used Collins’s old magazine feature to introduce the town to her father highlights a bitter irony: Collins’s past work, once a source of pride, becomes a tool that endangers her home. That irony forces her to reconsider the power of storytelling.

Photographs, articles, and records are not neutral; they can preserve a place or expose it to exploitation. Her decision to travel with Brady to document other towns Sullivan targeted is therefore a commitment to memory as civic resistance.

She uses the very skill she had been avoiding to protect histories like her own.

The reunion of Earnest and Adeline provides a quiet resolution to this theme. Once the truth is named and the lovers see each other again, the past is no longer only pain— it becomes peace.

Collins’s abilities returning after that reunion signals that memory can be restorative when handled with care. In Soul Searching, the past is not portrayed as something to escape or romanticize.

It is a living force that demands recognition, and healing comes when characters face it honestly, preserve what matters, and refuse to let powerful outsiders erase it.