Space Vampire Summary, Characters and Themes

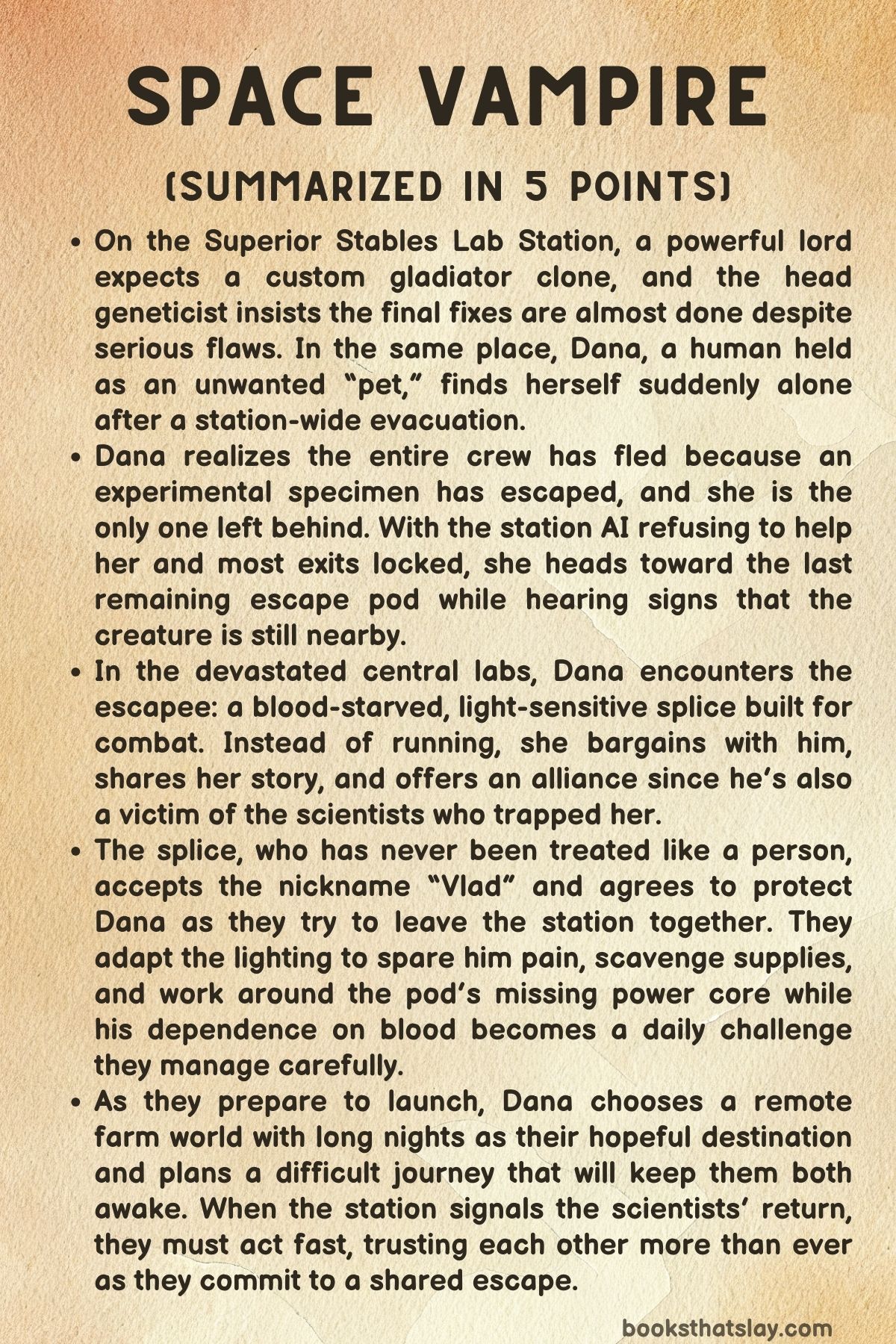

Space Vampire by Ruby Dixon is a fast, steamy sci-fi romance set on an abandoned lab station at the edge of space. A human woman, Dana, has been held captive as a “pet” by geneticists.

When a dangerous experimental soldier escapes and the station evacuates, Dana is left behind. Instead of becoming prey, she makes an unexpected deal with the escapee—an engineered, blood-dependent warrior she names Vlad. The story follows their tense alliance turning into trust and love as they fight for survival, freedom, and a future far from the people who made them monsters in someone else’s eyes.

Summary

On Superior Stables Lab Station, a high-status client demands progress on a custom gladiator clone. The stablemaster of Lord va’Dor wants assurance that the latest splice will be ready for delivery.

Head Geneticist Nasit sa’Wost reports that the clone has shown serious defects—blood deficiency and a violent reaction to light. He insists these problems are being corrected and that the final version is still on schedule.

The conversation frames the project as property and weapon, not a person.

Not long after, Dana, a human woman kept on the station against her will, wakes up in a laundry chute. She had been treated like a novelty animal by Nasit, forced into obedience and isolation.

Her first sense is that something is wrong: the usual noise and movement of the station are gone. She remembers alarms about an escaped specimen, but now there are no footsteps, no voices, and no staff.

Trying to leave the chute area, she discovers the doors don’t acknowledge her access. The station’s AI, which used to respond to commands, ignores her completely.

As she moves through empty corridors, she realizes the evacuation must have happened quickly, and nobody bothered to take her.

At a viewport, Dana sees the worst proof of it—every escape pod is gone except a single one still docked. The message is clear: the scientists fled and abandoned her.

Her first instinct is to run to the last pod, but a crash from the central labs tells her the reason for the evacuation is still aboard. If she rushes in blindly, she could end up cornered.

She needs something to defend herself with, but most tools and weapons on the station are made for large alien hands. She improvises, snapping a cleaning bot’s squeegee into a flexible rod and gripping it like a spear.

Dana creeps toward the lab complex and finds the doors forced open from the inside. The scene inside is destruction—equipment smashed, storage ripped out, and blood bags drained and discarded across the floor.

The escaped splice, labeled Project va’DorV8. 3, is there, frantic with hunger.

He is tall and blue-skinned, his eyes red, fangs visible, and a tail lashing behind him. His condition is obvious: he is driven by a need for blood and overwhelmed by the bright lab lights, which burn his eyes and skin.

When he senses Dana’s fresh blood, he turns toward her like a predator ready to feed.

Dana reacts quickly, slamming the light controls to full brightness. The splice recoils in pain, snarling for her to shut them off.

Instead of fleeing, Dana speaks. She tells him she is not one of his captors.

She explains she was kidnapped and kept as a pet, and that the people who built him are her enemy too. She makes a bold offer: if he is against them, then they can help each other.

The splice hesitates, thrown off by her refusal to cower. When she asks his name, he says he only has a batch number.

She decides he needs a real identity and calls him Vlad. He accepts the nickname, intrigued by her nerve and by the way she talks to him as if he matters.

He promises he won’t kill her.

With that fragile pact, they prepare to escape. Vlad uses his strength to tear open sealed doors, clearing paths Dana couldn’t cross alone.

To make the station more survivable for him, Dana uses a severed finger from one of Nasit’s assistants as a temporary authorization key. With it, she accesses the lighting system and programs dim, customized illumination that won’t injure Vlad.

Under the softer light, she studies him more closely and sees how much he has been altered—built for combat, engineered for obedience, and punished by his own biology. The two of them head for the pod bay, only to find the last escape pod is useless because its power core has been drained.

Dana starts recharging it, calculating that it will take about a week.

They settle in for that week together, choosing the captain’s quarters as a base. The station is dead quiet, but full of supplies left behind.

Dana and Vlad raid abandoned rooms for clothes in her size, weapons he can handle, credits, and valuable items they can trade later. As days pass, Vlad’s hunger grows worse.

He tests station food and can barely keep it down, confirming that he needs blood to function. Dana makes another bold choice: she offers her own blood in small amounts so he doesn’t lose control.

Vlad feeds carefully, stopping the moment she shows strain. His bites heal quickly on her skin, and the act shifts from necessity to intimacy.

Their routine becomes a bond, and trust slowly replaces fear.

With the pod charge rising, Dana searches station records for somewhere they can disappear. She chooses Cassa II, a farming world known for long nights and weak local enforcement.

The darkness will protect Vlad, and the loose authority means bribes can buy identity implants and remote land. Dana downloads maps, survival data, and transit routes.

Vlad admits a major problem: he can’t enter stasis for the four-month journey. The nutrient feeds in the pod won’t work for him.

Dana decides they will stay awake and he will keep feeding on her during the trip. They strip out extra stasis chambers to save power and pack the pod with one-person rations, gear, and everything valuable they can carry.

Just as they finish loading, the station AI announces an incoming ship arriving within an hour. The scientists are returning.

Dana knows that once they dock and cancel emergency mode, the pod’s launch override will lock. She and Vlad don’t wait.

Trusting her judgment, he straps in beside her, and they launch immediately.

In deep space, Dana confirms no pursuit. The danger of being hunted fades into the distance.

Vlad worries she might regret tying herself to a creature like him, especially once the adrenaline wears off. Dana answers without hesitation that she loves him.

He returns the feeling, not as a programmed soldier but as someone choosing her back.

Four months later, they reach Cassa II under a night sky. The landing is cold and quiet, just as Dana planned.

At the docks, she meets an official named Vargis and offers credits plus a valuable vase as a bribe. The deal works.

She and Vlad receive identity implants and legal homesteading papers for a remote northern region. With new names, a claim to land, and the cover of darkness, they step out together into their new world—no longer captive and experiment, but partners building a life on their own terms.

Characters

Dana

Dana is the emotional and moral center of Space Vampire, and her defining trait is resilient agency in the face of extreme objectification. Introduced as Nasit’s unwilling human “pet,” she begins the story in a position of absolute powerlessness, yet the moment the station empties, her survival instincts and self-respect snap into focus.

What stands out is how quickly she shifts from fear to problem-solving: she scavenges a weapon even in an environment built for bodies larger than hers, improvising with a cleaning bot’s squeegee because she refuses to be helpless. Her boldness isn’t reckless bravado so much as a deliberate reclaiming of control—she recognizes that the escaped specimen might be her only path to freedom, and instead of treating him as a monster, she treats him as a person.

That choice reveals Dana’s core strength: empathy that doesn’t weaken her, but sharpens her strategic thinking. Over the week waiting for the pod to recharge, her character deepens through self-sacrifice and trust.

She offers her blood not out of naivety, but because she understands the stakes and wants Vlad to keep his humanity. Their feeding routine becomes a symbol of mutual consent after her history of coercion, and it’s also where her courage is most intimate: she places her body in danger to build a relationship founded on choice.

By the end, Dana is no longer someone escaping captivity—she’s someone actively designing a future, selecting Cassa II for practical reasons, negotiating bribes, and arranging new identities. Her arc is a movement from being treated as property to becoming an architect of her own life, and love is not a rescue for her but a partnership she chooses on equal terms.

Vlad (Project va’DorV8.)

Vlad is both the threat that powers the plot and the wounded soul who humanizes it, embodying a classic “manufactured weapon who wants to be more” tension. He starts as a lab-born gladiator splice defined by deficits—blood deficiency, photosensitivity, uncontrollable hunger—and these traits make him terrifying in the sterile corridors of Superior Stables Lab Station.

Yet the story quickly reframes those same traits as evidence of brutal exploitation. He wrecks the lab and drains blood bags not out of sadism, but because he’s engineered to need it, and the light sensitivity that burns him under harsh lamps emphasizes how the station itself is hostile to his survival.

His early interaction with Dana shows a mind that’s raw but not empty: he can command, threaten, and assess, yet he’s deeply responsive to dignity. When Dana gives him a name, it becomes a pivotal moment—he moves from being a batch number to being a self, and her refusal to cower awakens something in him beyond hunger.

Vlad’s promise not to kill her is the first sign of moral choice in someone designed for violence, and his careful feeding later reinforces that he’s capable of restraint, tenderness, and reciprocal trust. He also carries an undercurrent of loneliness and identity uncertainty, hinted at in his fear that Dana might regret being with him; this insecurity makes him feel less like a predator and more like a person struggling to believe he deserves love.

Practical limitations, like his inability to enter stasis because nutrient feeds won’t work for him, keep him grounded as a biological reality rather than a romantic archetype, but they also deepen the intimacy of their bond since survival on the journey requires ongoing mutual dependence. By the time they land on Cassa II, Vlad has shifted from a runaway experiment to a partner and protector, not because he’s “fixed,” but because he’s finally allowed to be seen as more than a weapon.

Nasit sa’Wost

Nasit is the embodiment of cold scientific tyranny in Space Vampire, a character whose cruelty is normalized through intellect and institutional authority. As head geneticist, he views living beings primarily as datasets and outcomes, and the way he talks about Project va’DorV8.

3’s deficiencies frames suffering as a technical inconvenience rather than a moral problem. His ownership of Dana as a “pet” reveals a personal perversity layered on top of professional ethics collapse: he doesn’t merely exploit humans and splices because the system allows it, he seems to enjoy the power imbalance and dehumanization.

Nasit’s role is less about direct confrontation and more about shaping the horrors the protagonists are escaping—he is the architect of Vlad’s torment and Dana’s captivity. Even in absence, his presence hangs over the station as the reason everyone fled, and as the figure whose return would mean recapture.

The severed finger of his assistant used as authorization is a grim symbolic reversal of his authority: the same bureaucratic control he relied on becomes a tool for his victims’ escape. He represents the story’s critique of unchecked experimentation and entitlement, making him a vital antagonist despite having limited page-time in the summary.

Lord va’Dor

Lord va’Dor functions as the distant power behind the project, and his importance comes from what he represents rather than what he personally does on the page. He’s the political or aristocratic force that commissions custom gladiator splices, treating sentient life as a commodity engineered for spectacle and dominance.

The stablemaster’s demand for updates on the splice suggests va’Dor’s impatience and the high stakes of delivering violence-capable creations to satisfy elite desires. Because he’s off-station and never directly interacts with Dana or Vlad, he reads as a systemic antagonist: the kind of figure whose wealth and influence create the market for suffering without having to witness it.

In that way, he expands the conflict beyond one abusive scientist into a broader culture that profits from engineered brutality.

The Stablemaster of Lord va’Dor

The stablemaster is a small but telling character who provides the opening note of the story’s world. His role is managerial and transactional; he demands progress updates in the same tone one might use for livestock or equipment.

That cold practicality signals how routine this kind of genetic exploitation is in the setting. Even though he doesn’t reappear, his early presence helps establish the hierarchy Nasit answers to and the broader infrastructure of ownership and violence that Dana and Vlad are fleeing.

The Station AI

The station AI is not a villain in the human sense, but it is a chilling representation of institutional indifference. When Dana tries to use doors or get help, the AI ignores her, implying either that she was never registered as a person worth protecting or that emergency protocols don’t recognize someone of her status.

Its silence and refusal to respond intensify the horror of abandonment: Dana isn’t just alone because people left, she’s alone because the system is built to exclude her. Later, the AI’s automated announcement about the incoming ship returning becomes a ticking clock that forces the final escape, showing that even neutral systems can become threats when they serve oppressors by default.

The AI underscores a theme that captivity is sustained not only by cruel individuals but also by infrastructure that treats certain lives as invisible.

Vargis

Vargis appears briefly at the end, but he plays an important thematic role as a gatekeeper to freedom. He’s pragmatic, corruptible, and representative of the loose authority Dana intentionally seeks out on Cassa II.

The exchange of credits and a valuable vase for identity implants and legal papers shows Vargis as someone who operates within a gray economy, but crucially, his grayness enables Dana and Vlad to rebuild their lives. He’s not framed as heroic or malicious—he’s simply part of a world where rules bend for the right price.

Through him, the story closes on a realistic note: escape doesn’t end with running away, it ends with navigating power structures cleverly enough to become untraceable.

Themes

Captivity, Autonomy, and the Reclaiming of Self

Dana’s story begins in a space that treats her as property rather than a person. Her captivity under Nasit is not described as a single incident but as a condition of life: she is kept as a “pet,” trained into submission, and denied ordinary freedoms such as movement, recognition by doors, or even acknowledgment by the station AI.

The moment she wakes to silence after the evacuation, that silence functions like a cruel confirmation of how disposable she has been made. Everyone can leave, and she is not even considered worth rescuing.

Yet this abandonment becomes the spark for autonomy. The theme is not simply that she escapes; it is that she decides to act as a subject in her own life for the first time in a long while.

Her improvisation with the cleaning bot’s squeegee is a small but potent emblem of that shift: a tool meant for maintenance becomes a weapon because she refuses to remain powerless.

Her autonomy becomes even clearer in her first face-to-face encounter with Vlad. She does not understand his full nature or capabilities, but she chooses negotiation over panic, alliance over fear.

That choice is radical in context: she has been living in a system where decisions were made for her body and future. Now she makes a decision that carries risk, but it is her risk to take.

Throughout the week on the abandoned station, Dana continues to reclaim control through practical agency—choosing where they live, what they scavenge, what destination they set, and how they will survive a four-month flight. The text underscores that freedom is not handed to her by rescue or fate; it is built through repeated acts of will.

Even the final step on Cassa II feels less like arrival at safety and more like completion of a transformation: Dana is no longer a creature in someone else’s cage, but a woman defining a new life on her own terms. In Space Vampire, autonomy is both a physical escape and a psychological restoration of personhood.

Monstrous Bodies and Human Recognition

Vlad is introduced as a feared escaped specimen, a creature designed for violence and blood hunger, and made visibly alien by blue skin, fangs, tail, and red eyes. In many stories, this kind of figure remains a threat to be contained or destroyed.

Here, the theme turns on recognition: what makes someone a “monster” is not only biology but the social role forced on them. Vlad’s suffering—blood deficiency, photosensitivity, hunger that overrides reason—comes from being engineered as a tool for another man’s entertainment and power.

His aggression in the lab is framed as starving survival, not moral evil. The abandoned station becomes a stage where the usual categories of civilized scientist and savage creature collapse.

The scientists fled, leaving behind order, protocols, and moral claims. The “monster” is the one left in pain, hunted, and hungry; the “civilized” people are those who created him and ran.

Dana’s response is central to this theme. She talks to him like a person before she knows anything about him, and that act creates a new identity for him.

He has only a batch number, a label that denies individuality. Her nickname “Vlad” is an informal human gift, an identity rooted in relationship rather than ownership.

The trust that grows between them depends on mutual recognition: she admits her own dehumanization as a “poodle,” and he recognizes her bravery instead of treating her as prey. Their feeding arrangement deepens this theme.

Blood is the sign of his monstrousness, yet he takes it with consent, restraint, and care, healing her bites and stopping before harm. The story treats monstrosity as a condition that can be reshaped by ethical connection.

This theme does not claim that Vlad is secretly human inside; it suggests that dignity and moral agency can exist in bodies that society has defined as inhuman. Dana and Vlad form a bond precisely because both have been denied personhood by the same system.

Their relationship becomes a counter-argument to the station’s logic: engineered bodies and captive humans are still subjects, still deserving of names, choices, and affection. In Space Vampire, humanity is shown as something that emerges through how beings see each other, not through species or design.

Survival as Cooperation and Mutual Care

Once the evacuation leaves Dana and Vlad alone, survival stops being an individual contest and becomes a shared project. Dana cannot escape without someone strong enough to open sealed doors; Vlad cannot function without dim light, blood, and a partner who sees him as more than a specimen.

Their journey on the abandoned station is full of practical cooperation that also carries emotional meaning. Dana’s technical cleverness—using a severed finger as access authorization, reprogramming lighting, finding records, choosing the destination—pairs with Vlad’s physical capacity to tear open barriers and defend their fragile safety.

Neither can replace the other. This interdependence is not portrayed as weakness; it is framed as the natural answer to a hostile world.

The feeding arrangement is the clearest expression of survival through mutual care. Dana’s offer is not just a solution to hunger; it is a deliberate act of trust that places her body in his hands.

Vlad’s careful restraint is equally deliberate, showing that survival can be anchored in ethics. Their routine feeds two needs at once: his biological requirement for blood and her need to matter to someone after being treated as disposable.

Importantly, the theme avoids romanticizing sacrifice as pure suffering. Dana monitors his intake, he stops to protect her, and her wounds heal quickly.

The story makes consent and safety part of the survival system, not an afterthought.

Over the week, the station becomes a training ground for joint living. They raid rooms together, share quarters, plan logistics, and make decisions in a rhythm that resembles partnership rather than rescue.

Even the long voyage plan shows cooperation at its harshest edge. Stasis would have eased her burden but is impossible for him; instead she chooses wakefulness, accepting the cost because their survival is tied.

Her choice is not framed as blind devotion but as a clear-eyed strategy rooted in care.

By the time they reach Cassa II, their relationship has turned survival into a practiced way of being together. The bribe to Vargis and the new identities are not a lone hero’s triumph; they are the final cooperative act.

Space Vampire presents survival as something stronger than toughness alone: it is the capacity to build a small, ethical world with another person when the larger world has failed you both.

Love as a Path to Healing and Freedom

The romance between Dana and Vlad grows in a setting filled with fear and deprivation, which makes it less about instant attraction and more about gradual healing. Dana’s past contains sustained humiliation and emotional erosion; Vlad’s past is a laboratory that taught him to see himself as a batch number and a weapon.

When they meet, both are in crisis. Their love forms not because the crisis disappears, but because they respond to it together in ways that restore dignity.

Dana is bold and direct with him, refusing to cower. Vlad listens, makes promises, and honors them even when hunger pushes against restraint.

This shared respect becomes the foundation for affection.

The theme shows love as something that repairs distorted self-images. Dana has been trained into smallness, yet Vlad’s gratitude for her speaking to him “like a person” reflects back a truth she needs too: she is a person.

Each time she chooses to trust him—staying in the lab, offering blood, insisting they remain awake on the voyage—she is also choosing to believe she is worthy of connection. Vlad, on the other hand, learns that he is not defined only by engineered appetite.

He is capable of care, tenderness, and loyalty. The way he worries that she might regret being with him reveals an emerging selfhood that wants to be loved for more than usefulness.

Love here is also linked to freedom in a concrete way. Their bond motivates the risks needed to leave the station before the scientists return.

It shapes their destination choice, with Dana selecting a world built for Vlad’s needs as much as her own. Their future on Cassa II is not merely a safe hiding place; it is a shared life where love can exist without surveillance or ownership.

The final step into the cold darkness is meaningful because it is taken together, equal partners in a new beginning.

This theme avoids treating love as a magical cure that erases trauma. Dana still carries memory of captivity; Vlad still carries biological constraints.

But love gives them a context where those burdens do not rule them. It creates a private world of consent, name-giving, mutual protection, and chosen family.

In Space Vampire, love is not a reward after escape; it is part of the escape itself, a force that turns survival into a life worth living.