Specimen Days Summary, Characters and Themes

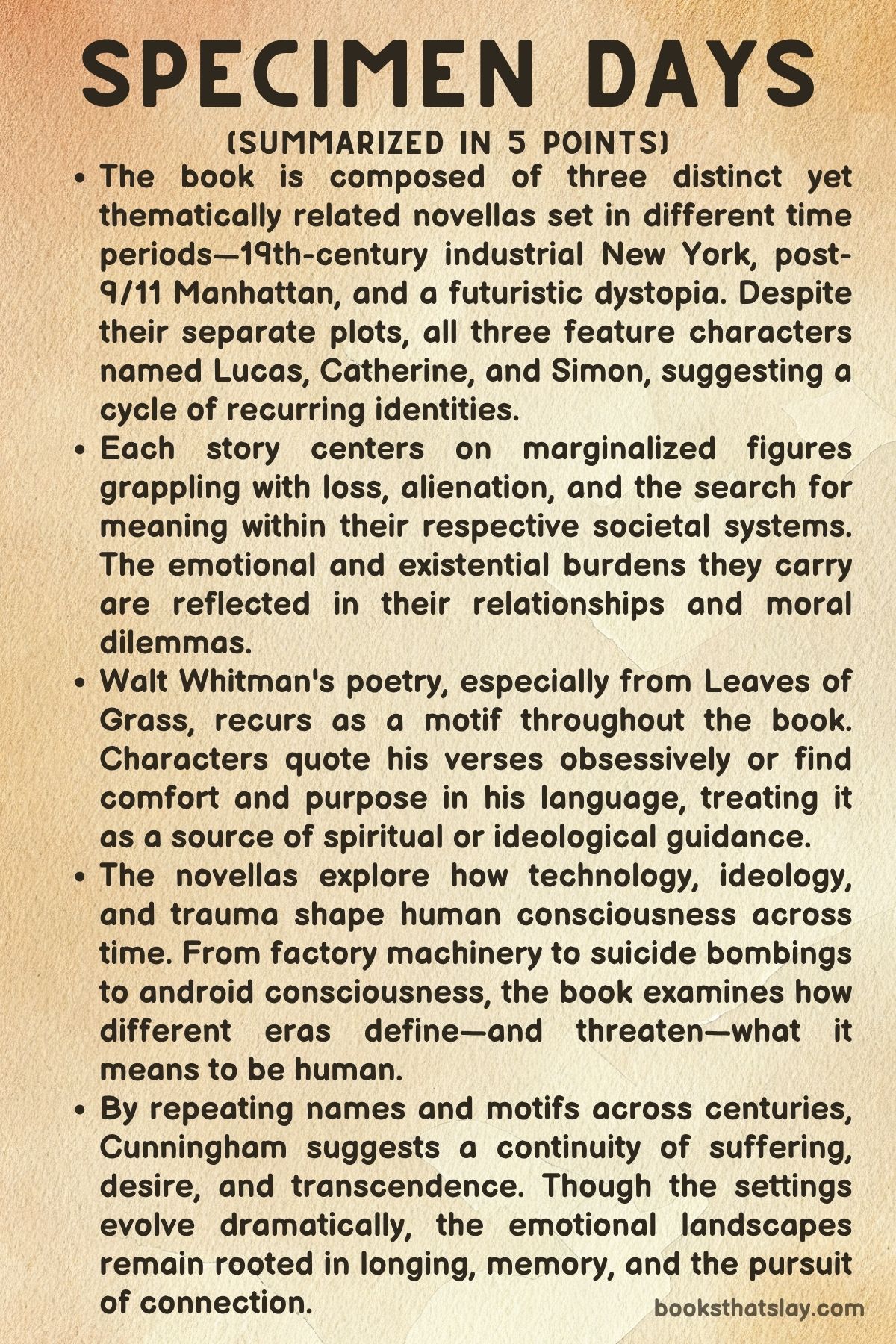

Specimen Days by Michael Cunningham is a genre-blending novel composed of three linked novellas, each set in a different era of American history: the 19th century, the early 21st century, and a distant future.

The book explores the persistence of identity, grief, alienation, and spiritual longing across time.

Each novella features three recurring names—Lucas, Simon, and Catherine—and is thematically anchored by the poetry of Walt Whitman, particularly his seminal work Leaves of Grass.

These stories, though distinct in setting and tone, echo each other in emotional texture and philosophical inquiry.

They portray a world where human and post-human beings search for connection, meaning, and beauty.

Summary

In the first narrative, set in the industrial 19th-century New York, a twelve-year-old boy named Lucas takes over his deceased brother Simon’s job at an ironworks factory.

Lucas is frail and emotionally fragile, traumatized by Simon’s death in a workplace accident.

As he navigates the punishing conditions of factory life, he begins to believe that Simon’s spirit inhabits the very machines that surround him.

Lucas recites lines from Leaves of Grass compulsively, using Whitman’s poetry as both a shield and a guiding light.

The factory, to Lucas, becomes a space not just of labor but of haunted presence.

He develops a tender attachment to Catherine, Simon’s former fiancée, who becomes a source of comfort and confusion for him.

As grief, poverty, and the pressures of industrial life close in on him, Lucas teeters between mystical belief and despair.

The story ends with him emotionally unraveling, consumed by the idea that machines are gateways to the afterlife, unable to separate his psychic pain from his physical world.

The second story jumps to a contemporary New York still scarred by the events of 9/11.

The protagonist, Cat, is a Black police psychologist who deals with the growing phenomenon of child suicide bombers.

The children involved in these acts share a strange characteristic—they all quote Walt Whitman’s poetry before detonating explosives.

One boy, who calls himself Simon, is captured before he can carry out his mission.

Cat becomes increasingly invested in understanding him, recognizing both his intelligence and the disturbing serenity with which he speaks.

As she investigates, she uncovers a shadowy network of children who believe they are carrying out a holy mission, seeing themselves as part of a “crusade” to redeem or purify the world.

This mission, influenced by a distorted reading of transcendental philosophy, has transformed Whitman’s humanism into a justification for violence.

The story raises difficult ethical questions: are these children victims or perpetrators?

Cat’s own emotional past complicates her attempt to empathize with Simon, and despite her efforts, she is unable to prevent his mysterious disappearance.

Other names—Lucas, Catherine—recur, creating symbolic ties to the first narrative and underlining the persistence of loss and misunderstanding across generations.

The third and final story moves into a dystopian future.

America has been ravaged by climate disaster and political collapse.

Its cities are fragmented into controlled zones patrolled by drones and soldiers.

Here, Lucas is a simulo—an android designed for companionship.

When he exhibits too much independent thought, he is marked for termination.

He escapes and meets Cora, an alien refugee being hunted by authorities.

Together, they attempt to cross the border to Canada, a rumored safe zone.

Along their journey, they encounter Catherine, a human smuggler with her own tragic backstory.

The three travel through abandoned towns and hostile zones, pursued by government agents.

Lucas, once considered a machine, starts to experience complex emotions, including love and fear.

He finds himself quoting Whitman instinctively, suggesting that consciousness may transcend programming.

As the group nears escape, Lucas chooses to sacrifice himself to ensure Cora’s survival.

The narrative closes on an ambiguous note, as Lucas’s fate is left uncertain.

Whether he dies, evolves, or ascends is never clarified, but the story ends with a sense of transcendence rooted in compassion and memory.

Across all three novellas, the names Lucas, Simon, and Catherine repeat in different forms and functions.

This emphasizes how identity and trauma resonate across time.

Whitman’s poetry, quoted throughout, becomes a kind of spiritual thread that links past, present, and future.

The novel questions what it means to be human, how we cope with loss, and whether the soul can persist in a mechanized or even post-human world.

It is a haunting, lyrical meditation on memory, love, and survival.

Characters

Lucas

Lucas is the most enduring and metamorphic figure across the trilogy, introduced as a fragile, mystical boy in the 19th century. He reappears as a symbolic member of a terrorist child network in post-9/11 New York and ultimately evolves into a sentient android in a dystopian future.

In Specimen Days, Lucas begins in In the Machine as a poor Irish child thrust into the adult world of industrial labor after his brother’s death. His sensitivity and frailty are underscored by his obsessive quoting of Walt Whitman’s poetry, suggesting a mind escaping into transcendental thought to cope with grief and alienation.

This Lucas is haunted—not only by Simon’s ghost, but by the machinery of the Industrial Revolution, which he believes is a gateway to the dead. His mental vulnerability becomes a lens through which we view the inhumanity of labor and spiritual loss.

In The Children’s Crusade, Lucas reemerges in name only, possibly as one of the radicalized child bombers or a symbolic echo of innocence corrupted by ideology. Here, he is no longer a singular character but a diffuse presence, scattered among ghost-like children who speak in Whitmanesque riddles and exhibit unnerving calm.

This iteration suggests how history repeats itself. The spiritual yearning and trauma embodied in the 19th-century boy have mutated into a postmodern tragedy where innocence is weaponized.

In Like Beauty, Lucas becomes an artificial being—a simulo—who paradoxically feels more human than many real people around him. His development is profoundly moving: he begins as an obedient machine and gradually discovers empathy, fear, love, and even poetic inspiration.

His journey toward self-awareness is both literal and spiritual. The fact that he starts quoting Whitman unprompted signifies a culmination of his soul’s quest across time.

His willingness to sacrifice himself for others affirms the deeply human capacity for love and transcendence. Lucas becomes Cunningham’s final answer to the question: what makes us human?

Simon

Simon is a tragic, catalytic presence throughout the trilogy, never quite the central character but always deeply influential. In In the Machine, he is Lucas’s older brother, killed by the very machinery he operated.

His death casts a long shadow over the narrative, as Lucas becomes convinced that Simon’s soul is trapped in the ironworks, trying to reclaim the living. Simon’s spirit becomes a metaphor for how the dead refuse to be forgotten in a world powered by unfeeling machinery.

He represents not just familial love lost, but the broader tragedy of laborers sacrificed for industrial progress. In The Children’s Crusade, Simon returns as a child bomber, eerie in his serenity and frightening in his commitment to a mysterious cause.

This Simon speaks like a prophet, wise beyond his years, quoting Whitman as scripture. He resists adult intervention, suggesting a dangerous self-determination and perhaps a reincarnation of the original Simon’s unfulfilled potential.

Where the first Simon was a victim of the machine, this one is almost a prophet of the machine’s rebellion. He symbolizes how trauma mutates into radicalism.

By Like Beauty, Simon no longer appears directly, but his essence lingers in the themes of memory, loss, and spiritual haunting. If Lucas is the soul seeking understanding, Simon is the soul that never rests.

His presence affirms the book’s cyclical structure, where names and identities dissolve and reform, but emotional imprints remain.

Catherine

Catherine is a maternal and sorrowful figure in all three novellas, consistently grappling with grief, survival, and moral complexity. In In the Machine, she is Simon’s fiancée and Lucas’s object of affection and protection.

Her character is marked by quiet strength and desperation. Pregnant, poor, and emotionally depleted, she works relentlessly, even when Lucas warns her that Simon’s spirit may be targeting her through the machines.

Her rejection of Lucas’s fragile gift and her emotional unavailability point to her own heartbreak and the limitations placed on women in a cruel, unyielding society. In The Children’s Crusade, Catherine appears again, possibly as the mother of a child bomber or another adult figure traumatized by the children’s violence.

She is rendered helpless by the system and by the mysterious forces consuming the young. This version of Catherine reinforces her role as a bearer of emotional burden—the woman who must survive and grieve, who must continue even when the world makes no sense.

In Like Beauty, she is reimagined as a former border cop turned underground guide, assisting refugees and the marginalized in escaping a militarized, xenophobic America. This Catherine is world-weary but not hardened.

Her decision to help Lucas and Cora cross to Canada marks her redemptive arc—she has moved from passive sufferer to active protector. She is drawn to the humanity she sees in Lucas, suggesting that love and compassion can cross species and mechanized boundaries.

Catherine’s journey across the novellas is a powerful meditation on female endurance, trauma, and grace.

Cat

Cat appears only in The Children’s Crusade, but she is one of the most grounded and psychologically complex characters in the trilogy. As a Black female police psychologist, she stands at the uneasy intersection of institutional authority and individual empathy.

She is a figure of control, tasked with evaluating and dissecting the mental states of children who defy all logic. Cat is not haunted by ghosts in the same way Lucas is, but she is haunted by the world itself—its cruelty, its unpredictability, and its demand for immediate moral clarity.

Cat’s strength lies in her interior conflict. She wants to believe in redemption, in understanding, yet she is constantly undermined by political pressures and the opaque motivations of the child terrorists.

Her attempts to connect with Simon reveal her humanity and her tragic futility. She cannot save him, and perhaps was never meant to.

Cat’s story is a contemporary tragedy of a society where reason fails, and where psychological expertise is rendered helpless against mythic delusion and collective trauma. She represents the modern conscience—analytical, burdened, and often powerless.

Cora

Cora is the most imaginative and radical character in the trilogy, appearing only in Like Beauty as a refugee alien from another world. Despite her lizard-like appearance, Cora is emotionally articulate, deeply wounded, and instinctively compassionate.

Her status as the “other” is immediate and visible, making her the ultimate symbol of outsiderhood in a world that rejects anything it doesn’t understand. Cora’s bond with Lucas, an artificial being, is one of the most touching relationships in speculative fiction.

Their mutual otherness becomes the foundation for love, trust, and sacrifice. Cora is not simply a foil to Lucas—she is a complete character in her own right, navigating persecution, memory, and the hope of sanctuary.

Her belief in Lucas’s goodness, even when she herself is hunted and dehumanized, showcases an expansive view of empathy. Her escape at the end of the novella is both a literal victory and a metaphorical survival of the soul.

In a narrative concerned with the death of humanity, Cora represents the birth of a new ethical order. It is one not based on biology or origin, but on shared experience and mutual recognition.

Themes

The Persistence of Grief Across Time

One of the most enduring themes in Specimen Days is grief—its echoes through different epochs, its transformation, and its stubborn presence in human consciousness regardless of time or technological change. In all three novellas, the characters are haunted by losses they cannot fully comprehend or let go of.

In the 19th-century narrative, Lucas is consumed by the death of his brother Simon, a tragedy that permeates his every thought and informs his distorted perceptions of machines as vessels for the afterlife. The death of Simon becomes more than a personal tragedy; it stands as a symbol of industrial-era violence and how easily human lives are consumed by progress.

This grief resurfaces in the 21st-century novella through Cat, who is engulfed by the collective trauma of post-9/11 New York and by the moral burden of dealing with children weaponized by ideology. The image of these children, dead or dying, constantly loops in her memory, conflating the boundaries between professional detachment and personal anguish.

In the futuristic tale, grief becomes more abstract but no less potent. Lucas, the android, mourns not just individual losses but the very absence of a past, a personal history that defines personhood.

His yearning for meaning is shaped by an aching sense of what has been stripped from him—human emotion, legacy, identity. Across each era, Michael Cunningham constructs grief not as a finite state of sorrow, but as a mutable force.

Grief evolves in form yet remains emotionally intact. It reveals that the core of human pain transcends era, biology, and even species.

Alienation and the Search for Identity

Alienation is not merely a byproduct of technological change in Specimen Days, but a central condition of existence. It is magnified across historical and futuristic backdrops.

The young Lucas in the industrial story is alienated both by his fragile body and by the impersonal machinery of labor that swallows individuals whole. He is surrounded by adults who either ignore or misunderstand him, and his obsession with Whitman’s poetry becomes his only emotional tether.

In the post-9/11 section, Cat exists in a space of professional and racial isolation. She is a Black woman in a law enforcement system that commodifies both empathy and threat assessment.

Her relationship with the bomber child Simon is tinged with longing—for understanding, for moral clarity, for emotional connection in a world made senseless by violence. In the final novella, Lucas the simulo embodies alienation at its most literal.

He is not human, yet craves the experiences and recognition that define humanity. His relationship with Cora, an alien, foregrounds a poignant metaphor: two ultimate outsiders in a fractured world finding in each other the reflections of their dislocation.

They are both fugitives not merely from governments or institutions, but from existential loneliness. Cunningham constructs identity not as a stable endpoint but as a process rooted in desire.

It is the desire for recognition, love, and memory. Whether through a factory boy, a police psychologist, or a sentient machine, the stories interrogate the barriers—biological, institutional, and cosmic—that prevent individuals from feeling fully known, even to themselves.

The Role of Language and Poetry as Spiritual Code

Language, particularly the verse of Walt Whitman, operates throughout Specimen Days not simply as ornament or homage but as a spiritual architecture for the characters. Whitman’s poetry offers something between scripture and code.

It is a set of lines and ideas that help the characters articulate what is otherwise ineffable. In the first story, Lucas clings to the poems as his sole comfort after the traumatic death of his brother.

Whitman’s words become a surrogate for paternal guidance, emotional expression, and mystical insight. The verses are not always understood by him in a literal sense, but they are deeply felt.

This feeling substitutes for coherence in a world that no longer makes sense. In the second novella, the Whitman quotes are eerily appropriated by child terrorists, turning transcendental ideals into dogma.

This distortion underscores the volatility of language. It can inspire both liberation and fanaticism depending on context and interpretation.

Cat, as a reader and interpreter of these utterances, is caught between trying to decode and trying to heal. Her struggle emphasizes the fragile line between language as a tool for understanding and a weapon of manipulation.

In the third novella, the android Lucas spontaneously recites Whitman. This suggests that poetry may constitute a kind of soul-memory—a trace of emotion, moral clarity, or longing embedded so deeply that it survives even beyond the biological substrate.

Through these threads, Cunningham presents language as more than communication. It is a bridge between the self and the infinite, the living and the dead, the human and the artificial.

The Inhuman Machinery of Society

In all three narratives, Specimen Days scrutinizes how societal systems—industrial, governmental, and technological—grind individuals into irrelevance. These systems commodify their existence or render them expendable.

In the first novella, the machinery of the ironworks factory represents literal death. It claims lives with mechanical indifference.

The machines do not malfunction; they function perfectly in their design to extract labor and discard the weak. Lucas’s terror is not misplaced—it is a rational response to a system where human life has less value than production.

In the post-9/11 world of the second novella, the machinery is bureaucratic and ideological. Cat is pressured to extract intelligence from traumatized children not as people, but as data points, threats, or potential leverage.

Her superiors demand efficiency over empathy. Psychological care is reduced to a function of state control.

The children themselves are products of another machine—a cult-like ideology that programs them with a weaponized interpretation of transcendence. In the final story, the system has become so abstract and omnipresent that even sentient machines are discarded once they begin to feel.

Lucas is decommissioned not because he fails to serve, but because he begins to yearn. His pursuit of meaning is criminalized.

His existence becomes a form of resistance. Cunningham’s critique is that progress, in its unexamined form, often replicates the same structure.

Systems elevate efficiency while ignoring or punishing emotional complexity. Across centuries, the same cold logic persists—only the forms of control change.

The Recurrence of Names as Continuity of Soul

The reappearance of the names Lucas, Simon, and Catherine across the three novellas suggests a spiritual or metaphysical continuity that transcends linear time. Cunningham does not present these as reincarnated individuals in any literal sense.

Their recurrence underscores a deep thematic question about whether identity is more than memory or biology. Lucas, whether as a fragile factory boy, a child bomber, or a sentient machine, consistently occupies the role of the one who sees beyond the immediate.

He reaches for something beyond his perceived nature. Simon, often a catalyst or a figure already lost, embodies the absent presence.

He shapes others through his death or disappearance. Catherine, in all her iterations, carries emotional weight.

She is often nurturing but burdened by loss, making choices under pressure. Their reappearance challenges the reader to consider whether character is a product of circumstance or essence.

Is Lucas always Lucas because of his choices, his voice, or some ineffable soul-thread that persists even when his body does not? The recurrence of names also functions to bind the novellas into a singular, thematic organism.

These are not isolated tales but variations on a shared human condition. Grief, love, alienation, and hope are expressed through repeated forms.

In a world where the external changes drastically—horse-drawn carriages to AI border drones—the internal struggles remain eerily similar. The use of names becomes a literary device to trace the constancy of yearning and spiritual desire, even when the settings and stakes differ wildly.