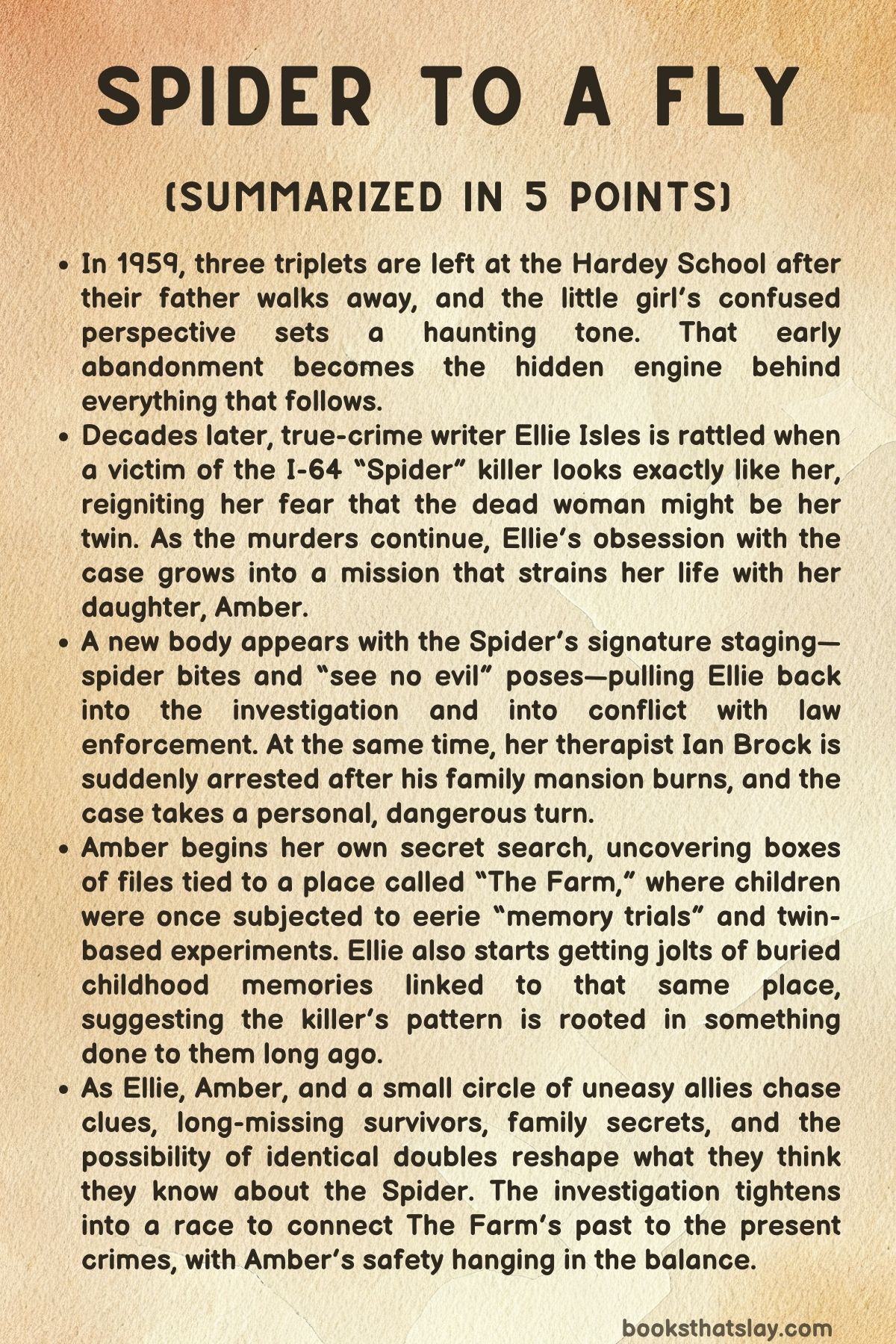

Spider to a Fly Summary, Characters and Themes

Spider to a Fly by J.H. Markert is a psychological thriller centered on a notorious interstate serial killer and the survivors shaped by a secret childhood program. The story follows Ellie Isles, a true-crime writer in Ransome, Kentucky, whose life has been defined by the I-64 “Spider” murders ever since a victim who looked exactly like her was found.

When Ellie’s trusted therapist, Ian Brock, is arrested after his family mansion burns, the investigation turns from professional fascination to personal danger. As Ellie and her daughter Amber search for the truth, erased memories of a place called the Farm return, exposing an experiment in twins, violence, and control.

Summary

In 1959 a father leaves his triplet children at the Hardey School for Idiotic Children. He walks them inside, points out a pond and birds they can’t sense, then says he forgot something in the car and never returns.

The children’s abandonment becomes the first crack in a long, hidden history.

Decades later Ellie Isles lives in Kentucky with her twelve-year-old daughter Amber. A news report announces the seventeenth victim of the I-64 “Spider” killer: Sherry Janson Brock.

Sherry’s face is identical to Ellie’s. Ellie also remembers a sudden, unexplained sickness on the day Sherry died, as if her body knew.

She becomes convinced Sherry was her twin, separated from her in childhood. Ellie’s fear of men and public places intensifies, but she channels her fixation into work, moving to Ransome and becoming a respected true-crime author.

She builds “Spider Web,” an online database that gathers tips, identifies unnamed victims, and tracks the killer’s pattern.

A new body is found along I-64, posed naked with spider bites and hands covering the eyes in a “see no evil” arrangement. Ellie slips into the crime scene, certain it matches the Spider’s signature.

FBI Agent Brian Givens orders her out, but Police Chief Tracy Simmons lets her look briefly because Ellie’s database has helped before. The town is exhausted and terrified, filled with families waiting for names for the Jane Does the Spider has left behind.

Ellie’s therapist, Ian Brock, has been helping her probe gaps in her early life. During a session he abruptly ends things after a tense phone call.

That night Amber comes home after lying about where she went, dropped off by a boy in a red Audi, and mother and daughter clash. Amber then tells Ellie to turn on the TV: the Brock family mansion is burning.

Ian is led away in handcuffs. His adoptive parents, Bart and Karina Brock, are believed dead inside, along with the adopted son Royal.

As the fire shakes the community, Ellie begins experiencing sharp flashes of a childhood she can’t fully recall: a facility called the Farm, adults wearing theatre-style masks, and a cruel children’s game called “Spider and the Fly,” led by an older green-eyed boy named Romulus. Ellie also meets her new neighbor, Ryan Summers, a former cop whose scar and calm presence feel oddly familiar.

Amber is hiding her own secrets. She has been attending Ian’s support group for girls frightened of the Spider without Ellie’s knowledge.

She has also been messaging Deron “Deak” James, a thirty-year-old actor, and brought him to the Brock property earlier on the day of the fire. Deron stopped replying afterward.

Soon anonymous texts lead Amber to a concealed shed near the burned estate. Inside she finds charred boxes stuffed with records.

With her friend Molly she hides the boxes and discovers folders labeled “The Farm,” “Memory Trials,” and “The Happiness Project. ” The documents read like clinical files on children, suggesting years of planned manipulation.

Meanwhile Ellie’s Spider Web network identifies the newest highway Jane Doe as Erin “Rosie” Matthews. Almost immediately a forum message asks Ellie if she remembers the Farm.

The phrase triggers more images: an iron gate, spiders crawling over her skin, a dark room, and someone calling her “Sherry. ” At the Brock property someone dumps a mannequin staged like a Spider victim, with “Victim #0” written on it and a note addressed to Ellie.

The message implies the Spider had a first target long before the recorded murders—possibly someone still alive. Kenny Brock, another adopted sibling, lashes out at Ellie for exposing the family’s past.

Givens invites Ellie to assist the task force. Lab results link semen from Spider scenes to blood found at the Brock house, appearing to match Ian’s DNA.

In custody Ian insists he did not kill the women and says Bart and Karina were far more dangerous than the town knew. He confirms Ellie’s fear: Sherry was her twin.

Ian argues that if Ellie had a twin, he might too, and that his twin could be the Spider.

Ellie’s body reacts violently to Ian’s words, as if spiders are crawling over her, and a locked memory opens. She sees herself at the Farm, covered in real spiders while a green-eyed boy laughs and calls her “Sherry.

” She cannot tell if the boy was Ian or someone who looked like him. Despite her doubts, Ian is formally charged for the murders.

Amber confronts Kenny to recover the stolen boxes. She finds him burning the files, drunk, armed, and unraveling.

He reveals the Farm housed thirty children arranged as fifteen sets of twins, all part of an experiment designed to create aggression and obedience. He talks of genetic “warrior” traits and abuse, then kills himself.

Amber grabs a surviving envelope labeled “Remus and Romulus” and escapes, but a figure sabotages her car, forces her off the road, and abducts her.

Ellie panics as Amber’s location goes dark. Visiting Ryan, she notices tulips that trigger a clear memory of a blue-eyed boy at the Farm who once comforted her with tulips.

Ryan is that boy, and his own memories are returning too. A former suspect, trucker Stanley Flanders, reappears with a bullet he believes came from a military sniper rifle near an old dump site, hinting at a killer with combat training.

On Spider Web, a disabled nurse named Lucy claims she is “victim 0” and that her captor is the Spider, but she goes silent. Ellie and Ryan trace Lucy’s case to Edward Slough, a Purple Heart Iraq sniper.

FBI raids his property, rescues Lucy alive, and finds endless spider cages and detailed murder charts. DNA confirms Edward is Ian Brock’s identical twin, clearing Ian.

Deron’s phone video then shows Jon Brock attacking Deron, mistaking him for Royal, and ordering gasoline, indicating Jon and Kenny set the mansion fire while Ian tried to protect Jon. Royal is alive and tells Ellie that Ian’s travel schedule matches every abduction and dump site.

When investigators map the trips, the pattern centers on woods behind the Brock estate.

Ellie and Ryan rush to the woods. Edward, trying to reach the original Farm, takes a sniper perch near a tower cabin, firing to drive police inside.

Jon is badly wounded. In the tower Ellie finds Ian holding a half-conscious Amber with black widow bites and a knife to her throat.

Ellie realizes Ian has been the Spider, using his therapist role and constant travel to choose victims, while Edward acted as his twin double. Ellie edges Ian toward a window so Edward has a clear shot.

Edward shoots Ian dead. Police then kill Edward as he attempts to flee.

Amber survives and begins recovering at home as Ellie, now facing the full truth of her past, tries to build a life beyond what the Farm made of its children.

Characters

Ellie Isles

Ellie Isles is the emotional and investigative center of Spider to a fly. Abandoned as a child and later left with fractured memories of The Farm, she grows into an adult who is both hypersensitive to danger and stubbornly determined to name it.

Her life as a mother and her life as a true-crime writer overlap until they’re basically the same mission: keep Amber safe by understanding the Spider. Ellie’s anxiety around men, her panic attacks, and her compulsive tracking of Amber’s whereabouts show someone whose nervous system never stopped living in the original trauma.

Yet she is not passive or fragile. She builds the Spider Web database, pushes into crime scenes, and earns a role with the task force because her pattern recognition is sharper than the professionals’.

Her deepest conflict is identity: the certainty that Sherry was her twin and that her own past is entangled with every victim. As memories return, Ellie becomes a person forced to reconcile two selves—one who survived by forgetting and one who must remember to save her daughter.

The story tracks her shift from fearful observer to active rescuer, and by the end Ellie’s courage is less about having no fear and more about moving through it for Amber’s sake.

Amber Isles

Amber begins as a twelve-year-old startled by a victim who looks like her mother, and over time she becomes a parallel protagonist whose choices repeatedly propel the plot forward. She inherits Ellie’s intensity but expresses it differently: where Ellie freezes, Amber pushes; where Ellie spirals inward, Amber vents outward in bursts of rage that she later hates herself for.

Her secret tattoo, hidden attendance at the support group, and clandestine investigations with Molly show a teenager trying to seize control of a story that has always victimized her family. Amber is also hungry for truth in a way that feels almost moral—she carries the humiliation of the Brocks turning Ellie away, and she converts that memory into a vow to keep digging.

Her relationship with Jon Brock highlights her vulnerability to manipulation and her craving to belong inside the mystery rather than outside it. When she is captured and nearly killed by black widow bites, Amber becomes the most literal “fly” in the narrative, paying the price for curiosity in a world run by predators.

Surviving that ordeal doesn’t just restore her body; it validates her toughness and her bond with Ellie. In the end, Amber emerges scarred but alive, a young woman who has seen how monsters are made and is determined not to become one.

Ian Brock

Ian Brock is written as a man of masks: therapist, suspected serial killer, traumatized twin, and former child experiment subject. His calm professional persona is persuasive enough that Ellie trusts him deeply, which makes his arrest and DNA connection to victims a devastating betrayal of safety.

Ian’s dissociative fugue claim fits a life shaped by The Farm’s conditioning, hypnosis, and identity experiments, and the narrative keeps him suspended between victim and villain for much of the book. When he confirms Ellie and Sherry were twins and suggests he might also have a twin who is the real Spider, he’s doing two things at once—offering Ellie a truth she needs and building a defense that could save him.

His relationship with family is equally layered: he appears loyal to Jon, protective to the point of self-destruction, and yet haunted by whatever Bart and Karina did to them as children. The final reveal that Ian is directly holding Amber hostage resets him as the Spider himself, and his death by Edward’s bullet closes his arc as a person who could never fully escape the predator role The Farm engineered in him.

Kendra Richards

Kendra Richards is Ellie’s closest ally and the story’s grounded conscience. As a reporter, she is used to violence and secrets, but unlike Ellie she can compartmentalize without collapsing.

Kendra’s friendship is practical—coffee meetings, urgent texts, showing up with wine when Ellie is unraveling—and also fiercely protective, as seen when she turns a gun on Stanley Flanders to keep Ellie safe. She operates like both witness and shield, following the case with professional distance while still believing Ellie’s instincts.

Kendra also functions as a social mirror: through her, we see how exhausted and frightened Ransom has become, how the Spider murders shape daily life, and how Ellie is viewed by outsiders. She’s the one who nudges Ellie toward human connection with Ryan, not because she’s naive but because she understands Ellie needs a tether to the present.

Kendra’s steady presence makes her a counterweight to the story’s paranoia: she believes evidence matters, but she also believes Ellie matters more.

Ryan Summers

Ryan Summers enters as a new neighbor who triggers Ellie’s fear of men, yet his familiarity and later revealed Farm connection position him as her most significant partner. His controlled manner, former-cop background, and almost military neatness make him glance-suspect at first, but the narrative reframes those traits as survival skills shaped by childhood trauma.

The scar under his right eye and the tulips memory anchor him as the blue-eyed boy from The Farm, and that recognition detonates Ellie’s buried past. Ryan is defined by dual instincts: protect Ellie and Amber in the present, and excavate the truth about what Bart Brock and The Farm did to them.

He is not a romantic fantasy figure; he’s a traumatized adult learning how to trust his own memories without letting them consume him. His methodical research with Ellie, and his willingness to stay close for safety, show him gradually choosing connection over isolation.

In the climax he becomes operationally brave, moving into the Farm tower with Ellie, helping maneuver Ian into the line of fire, and staying emotionally present afterward as the small possibility of healing opens.

Edward Slough

Edward Slough is the narrative’s most chilling embodiment of what The Farm produces. Introduced as a sinister caretaker of a paralyzed woman, he is later exposed as Ian Brock’s identical twin and an Iraq sniper whose obsession with spiders and control has metastasized into ritual murder.

His identity is built around dominance and aesthetic order: glass cages labeled with spider names, walls charting murders, and a private definition of himself as “the Spider” who hunts flies. Edward’s military history makes him lethally competent, and his choice to label his property “The Farm” is both misdirection and homage to his origin.

Yet he is not simply a separate monster; he is a mirror of Ian, showing how twins from the same experiment can diverge into different forms of violence. His final act—claiming to be “the Fly” who will return Amber while refusing to reveal his location—shows a warped desire to control the narrative even as it collapses.

His death at the hands of officers ends his arc as the predator who can’t imagine any world where he isn’t the one pulling strings.

Lucy Lanning

Lucy Lanning serves as the haunting proof that the Spider story began long before the highway victims. Once a nurse at The Farm and remembered as a “guardian angel,” she becomes Victim Zero—crippled, silenced, and hidden for nearly two decades.

Her paralysis does not erase her agency; she’s the one who risks everything to message Ellie through Spider Web, offering the first direct claim from inside the Spider’s house. Lucy’s presence reframes the murders as an extension of Farm conditioning rather than random evil, and her nickname in other people’s memories suggests she tried to protect children from the experiment’s cruelty.

The tragedy of Lucy is that she survives only by enduring captivity, and when she is rescued, her life becomes a living indictment of both Edward and the Brock system that made him. She is the quiet moral core of the backstory—proof that compassion existed in The Farm, even if it was crushed.

Kenny Brock

Kenny Brock is volatile, grief-soaked, and almost entirely governed by trauma he cannot metabolize. He appears first as an enraged family member blaming Ellie for the destroyed Brock image, then reappears as a man destroying evidence in a backyard firepit with a gun trembling in his hand.

Kenny’s drunken confession about The Farm—thirty children, fifteen sets of twins, abuse, the warrior gene, and “how monsters are made”—is one of the story’s clearest windows into the experiment’s scale. His references to Royal’s twin, and his insistence that they “fucked up,” suggest complicity mixed with horror, like someone who helped keep a system running just to survive it.

Kenny is tragic in his self-awareness: he knows what they became, but cannot live with it. His suicide in front of Amber is a final collapse of guilt and fear, and it also becomes a grim transmission of truth to the next generation.

Jon Brock

Jon Brock is the charming surface of the Brock family concealing something far more dangerous. To Amber he is seductive and manipulative, pulling her into half-truths and using her loyalty to keep their alibis aligned.

His desperation after the fire and his insistence on controlling Amber’s story point to someone used to managing appearances at any cost. The Deron phone video portrays Jon as violent, impulsive, and deeply entangled in whatever the Brocks are hiding, suggesting he may have inherited or learned predator behaviors from The Farm environment.

Yet Jon is also written as someone terrified of a larger force—possibly Ian or Edward—hinting that his cruelty is mixed with panic. When Edward shoots him, Jon is removed before any redemption or full confession, leaving him as a symbol of the second-generation Farm product: not necessarily the Spider, but engineered to orbit it.

Jeremy Brock

Jeremy Brock functions as the sibling who cracks the family denial. He is blunt, physically explosive, and emotionally raw, and his confrontation with Jon reveals how deeply the brothers are splintered by fear and suspicion.

Jeremy is the one who voices what others avoid: that their father might be the Spider, that Jon’s story is rotten, and that Sherry once called Ian a monster. His willingness to show a hidden photo and to tell Ellie about Jon coming home with gasoline and blood paints him as a reluctant truth-teller, someone who hates the family secret but hates the silence more.

He is not portrayed as purely heroic—his violence and instability are real—but he channels those traits toward exposure rather than concealment.

Royal Brock

Royal Brock is the absent-present ghost of the Brock family, believed dead in the fire and then revealed alive. His survival turns the Brock narrative into a living conspiracy rather than a closed tragedy.

Royal’s phone call with Ellie frames him as an informant more than an attacker; he lays out a logistical spider web connecting Ian’s travel patterns to victim dumps, insisting that finding the original Farm will find Amber. Whether fully trustworthy or not, Royal represents the sibling who stepped out of the family myth and returned holding leverage.

He is a key example of how Farm survivors can become either predators or whistleblowers, and the text keeps him morally uncertain but strategically crucial.

Bart and Karina Brock

Bart and Karina Brock are the dead architects of the Brock family’s public elegance and private horror. Their mansion, philanthropy, and social polish contrast violently with the implied truth that they were tied to chairs, murdered, and likely deserved to be feared.

Through memories and documents, Bart is linked to Mr. Laughy, a masked adult who hypnotized children to forget, while Karina’s role implies partnership in the experiment rather than ignorance.

They are not developed through direct action but through the gravitational impact of their cruelty: they adopted twins, participated in Farm trials, curated a fake legacy, and left behind children who cannot tell love from control. Even in death, they remain the shadow that drives every survivor’s breakdown.

Tracy Simmons

Chief Tracy Simmons is one of the few officials who recognizes Ellie’s value without surrendering authority. She balances skepticism and trust, letting Ellie view crime scenes briefly but also reining her in when needed.

Tracy is practical, tired, and responsible for a town worn down by serial murders, which makes her decisions feel driven by survival rather than ego. Her presence gives the investigation a human face inside law enforcement, and her cooperation with Ellie suggests a quiet respect for lived experience as evidence.

Brian Givens

FBI Agent Brian Givens plays the institutional counterpart to Ellie’s obsessive amateur drive. He is strict at the crime perimeter, then shifts into recruitment mode once he sees Ellie’s pattern insights and database capability.

Givens represents official power that is capable of learning rather than merely controlling. His willingness to show Ellie the DNA link and bring her onto the task force makes him a bridge between personal trauma and state investigation, even if the FBI’s early certainty about Ian also highlights how institutions can be misled by surface facts.

Arlo Butler

Chief Arlo Butler functions as the pragmatic coordinator of the war room, feeding Ellie and the team new evidence while maintaining a steadier distance than Tracy. His call bringing Ellie to the mannequin scene shows he recognizes both her emotional stake and investigative usefulness.

Arlo’s role is less about personality and more about representing the machinery of the case grinding forward, especially once The Farm connection becomes explicit.

Cindy Kern

Cindy Kern is a small but meaningful presence in Ellie’s immediate world. As a neighbor receiving lasagna and sharing porch conversations, Cindy represents normal life that Ellie is trying to keep afloat.

Her openness to newcomers like Ryan, and her everyday warmth, contrast with Ellie’s isolation and remind the reader of the community that exists outside the Spider’s web.

Molly

Molly is Amber’s partner in teenage investigation and the keeper of the “girl cave” basement where truth is sorted into piles. She embodies loyalty without glamor, risking her safety to help Amber haul boxes, decode documents, and hide their findings from the Brocks.

Molly’s basement becomes a symbolic counter-Farm: instead of experiments imposed by adults, two girls self-direct their search for reality.

Deron “Deak” James

Deron “Deak” James is the outsider lured into Brock drama and destroyed by it. As a thirty-year-old actor contacted online by Amber, he seems like a questionable but not malicious figure until his burned body is identified.

His phone video becomes crucial evidence of Jon and Kenny’s involvement in the fire, turning Deron into a posthumous witness whose death exposes the family’s violence.

Stanley Flanders

Stanley Flanders is Ellie’s old suspect, once convicted for sex trafficking and long framed in her mind as potential Spider. His reappearance creates a volatile collision between Ellie’s past theories and current reality.

Despite the threat he represents, Stanley arrives with a piece of physical evidence—the bullet from a sniper rifle attack—that pivots the investigation toward military connections and ultimately toward Edward. Stanley’s role highlights Ellie’s capacity to revise her certainties when new truth appears, and it also shows how evil in this world is plural, not singular.

Romulus and Remus

Romulus and Remus exist partly as names in surviving Farm files and partly as the childhood dynamic that shaped later monstrosity. The flashback game of “Spider and the Fly,” with a green-eyed boy called Romulus playing the Spider violently, sets up the twin motif as both mythic and clinical.

These names evoke predestination, brotherhood, and the way The Farm cast children into roles they could not escape. Whether tied directly to Ian and Edward or used as symbolic labels by the experimenters, Romulus and Remus represent the origin point where play was weaponized into training for domination.

Themes

Childhood Trauma and the Fragility of Memory

The story keeps returning to what was done to children at The Farm and how those experiences refuse to stay buried. Ellie’s life is shaped by sensations and flashes she can’t fully place—panic around men, nausea when Sherry dies, the crawling feeling on her skin that becomes a doorway to the past.

These moments show trauma as something stored not just in thought but in the body, resurfacing through smell, touch, objects, and sudden fear. Memory here isn’t a neat archive; it is fractured, defensive, and sometimes weaponized.

The children were trained to forget through hypnosis and fear, so adulthood becomes an unstable negotiation between what they feel and what they can prove. Ellie’s work as a true-crime writer doubles as self-therapy: she is trying to solve a public case while also decoding her own blank spaces.

The novel also makes clear that memory recovery is not automatically healing. When Ellie remembers the spiders, the green-eyed boy, and being called “Sherry,” she doesn’t find comfort—she finds horror and responsibility.

Ryan’s memories return in parallel, suggesting that shared trauma can create a dispersed, collective truth that only becomes visible when multiple survivors start recognizing the same scars. Even the “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil” staging of victims functions like a cruel mirror of what was forced on the children: silence, blindness, obedience.

In Spider to a fly, remembering is dangerous because it threatens powerful people and revives unbearable emotions, yet forgetting is equally dangerous because it lets the cycle continue. The theme argues that trauma distorts time; the past is never past, and recovery is less about perfect recall and more about surviving what comes back.

Identity, Twins, and the Fear of Being Replaceable

The revelation that Ellie and Sherry are identical twins redefines the murders as a crisis of selfhood. Ellie has lived under the shadow of a woman who looks like her, died like her, and may have shared her childhood captivity.

That resemblance isn’t just eerie; it creates an ongoing anxiety that Ellie’s identity is not singular. She fears that what happened to Sherry could have happened to her, and the story uses that fear to explore how fragile personal boundaries can be when biology, childhood conditioning, and violence overlap.

The Farm’s structure—thirty children arranged as fifteen pairs of twins—turns human beings into experimental variables, meant to test what can be produced, controlled, or replicated. In that system, individuality is treated as noise.

The theme asks what it means to be yourself when you were raised to be a counterpart, a data point, or a substitute. Ian’s defense strategy even leans on this logic: if Ellie had a twin, maybe he did too, pushing identity into a legal and moral maze.

The mirrored lives of Ian and Edward intensify the same idea from another angle. Two genetically identical men diverge into therapist and killer, protector and predator, raising questions about agency versus design.

The “warrior gene” talk from Kenny further frames identity as something that might be engineered or triggered, not chosen. Amber also inherits this uncertainty.

Her secret rage, guilt, and attraction to danger feel like echoes of something planted before she was old enough to consent. The theme doesn’t claim people are doomed by biology; instead, it shows how the fear of replaceability can be used to control.

When identities are treated as interchangeable, violence becomes easier to justify. Spider to a fly pushes back by letting survivors reclaim who they are through connection, testimony, and choice, even when their origins were built to erase difference.

Predation, Control, and the “Parlor” of Power

The Spider killings are not only about death; they are about domination. Each victim is staged as a lesson in submission, with bodies posed to signal enforced silence and helplessness.

The killer’s ritual spiders, the black widow bites, and the repeated line “Step into my parlor” make predation feel like a philosophy rather than an impulse. The Farm extends this logic backward into childhood.

The game “Spider and the Fly” begins as play but is warped into rehearsal for terror, where one child learns power through cruelty and the others learn to freeze, obey, and dread being chosen. Adults at The Farm—masked, laughing, frowning—turn care into manipulation, using medical language and “projects” to hide abuse.

That institutional polish becomes another room in the parlor: control doesn’t need chains when it has authority, money, and secrecy. Bart and Karina Brock embody the respectable face of predation.

Their mansion, philanthropy, and adoptive family narrative hide a structured system of harm. Even Ian, whether guilty or not, becomes a symbol of how trust can be exploited: a therapist’s office is supposed to be safe, and the possibility that the therapist might be the Spider collapses the boundary between healing and hunting.

The theme shows predation as layered—sexual, psychological, social, and symbolic. Victims are mostly women on the margins: runaways, addicts, sex workers, the unidentified Jane Does that a town learns to overlook.

The Spider targets those society already treats as disposable, making his control easier. But the theme also reveals resistance.

Ellie’s database, Amber’s stolen files, and Lucy’s late-night messages are ways of refusing to stay trapped in someone else’s narrative. Predation relies on isolation; the survivors fight back by building networks and naming what was hidden.

Spider to a fly makes clear that the parlor is not just a murderer’s lair but any system that invites vulnerability and then converts it into power.

Motherhood, Inheritance, and the Struggle to Protect Without Smothering

Ellie’s relationship with Amber is the emotional engine of the plot, and it frames motherhood as both refuge and pressure cooker. Ellie wants to keep her daughter safe from the Spider, from men, from the world, but her protection is tangled with her own fear.

Tracking Amber’s phone, confronting her about lies, and hovering at the edges of her social life show how trauma can reshape parenting into surveillance. Ellie isn’t cruel—she is terrified of repeating history.

Yet Amber experiences that fear as a kind of cage, which pushes her into secrecy: the tattoo, the therapy group, the trip to the Brock house, the hidden boxes. This tension highlights how love can become controlling when it is driven by unresolved pain.

The theme also examines what parents pass down without meaning to. Amber’s bursts of rage and guilt mirror the Farm’s emotional conditioning, suggesting that inheritance is not only genetic but behavioral and atmospheric.

Ellie’s mission to uncover the truth becomes Amber’s mission too, turning the daughter into a partner in a war she never asked for. Their shared investigation is empowering, but it also blurs the line between guidance and burden.

The theme broadens through the Brock family. Adoption is presented as both salvation and exploitation: children are taken in under the guise of care, then rearranged into experiments.

Parent figures who should protect instead manufacture harm. Against that contrast, Ellie’s imperfect but genuine devotion stands out.

When Amber is bitten and abducted, Ellie refuses to collapse, and her search is fueled by the simplest maternal instinct: bring her child home. The ending, with Amber surviving and returning to Ellie’s hand, doesn’t erase the damage, but it reframes motherhood as persistence rather than perfection.

Spider to a fly suggests that real protection is not about controlling every step a child takes; it is about helping them face the world with truth, boundaries, and the knowledge that they are not alone.

Truth, Justice, and the Ethics of Watching Violence

The novel is saturated with true-crime culture, media pressure, and public appetite for horror. Ellie’s career depends on studying the Spider, building databases, and following patterns, and the town’s exhaustion shows what happens when a community is forced to live inside a narrative of serial murder.

Victims become numbers—seventeenth, twenty-ninth—and the term “Jane Doe” becomes a grim placeholder for lives erased twice: once by the killer and again by anonymity. The theme questions who gets to tell these stories and why.

Ellie wants justice, but she is also aware that her book brings attention and profit. Her intrusive entrance into crime scenes and her fame complicate her morality, not because she is villainous, but because the line between advocacy and spectacle is thin.

Kendra’s reporting adds another layer; she needs headlines, yet she also provides solidarity and risk-sharing. The town’s support groups, forums, and rumors reveal how fear can turn people into both witnesses and consumers.

When Ian is arrested and charged, the system latches onto a convenient explanation, showing justice as something vulnerable to narrative shortcuts. The search for “Victim Zero” further emphasizes that truth is often incomplete, and official timelines may be built on what is easiest to close rather than what is accurate.

At the same time, the theme doesn’t dismiss investigation; it shows ethical truth-seeking as communal labor. Ellie’s Spider Web network helps identify Erin Matthews, giving dignity back to someone society abandoned.

Lucy’s claim of being Victim Zero shows how survival can be a form of testimony even when speech is stolen. The theme ultimately argues that watching violence is not neutral.

It can enable predators, distort justice, or reduce suffering to entertainment. But it can also build empathy and action when guided by responsibility.

Spider to a fly asks readers to sit with that discomfort: to want answers without turning people into puzzles, and to pursue justice without forgetting the human cost behind every clue.