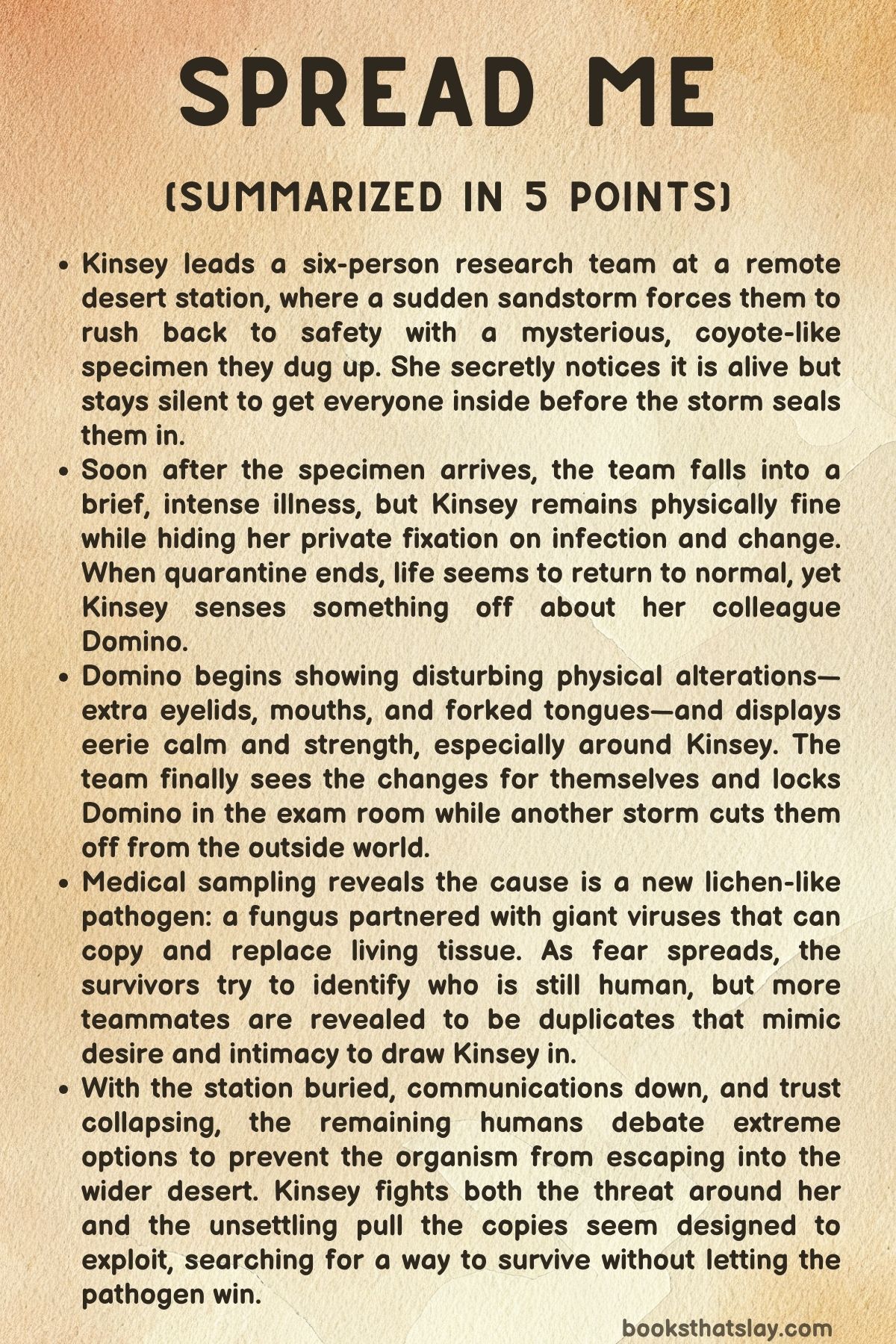

Spread Me by Sarah Gailey Summary, Characters and Themes

Spread Me by Sarah Gailey is a tight, unsettling science-fiction horror novella set in a remote desert research station. It follows Kinsey, a field leader whose professional restraint collides with a private obsession: viruses.

When her team digs up a buried, animal-shaped specimen during a storm, she makes a split-second choice to bring it inside. That decision turns the station into a sealed petri dish. As illness passes through the crew and something in the sand begins to copy, reshape, and seduce, Kinsey is forced to confront desire, agency, and what it means to want a thing for what it truly is.

Summary

Kinsey heads a small research team living in an isolated desert station. During a routine survey, the group uncovers an unfamiliar specimen buried in the sand.

A violent sandstorm is closing in, so they haul the creature back on a tarp. Kinsey, walking beside it, sees something impossible: the specimen inhales and coughs sand.

Station rules forbid bringing living organisms inside, but panic and the oncoming storm leave no time. Kinsey says nothing, urges everyone through the airlock, and they reach shelter just as the storm slams into the base.

In the exam room, the creature’s size and structure astonish them. It looks like a segmented, six-legged coyote, furred and long-snouted, its eye sockets clogged with sand.

While they argue about procedure and blame, the specimen shifts. Jacques grabs a leg by accident, and the creature snaps fully awake.

It thrashes wildly, spits sand, shows three tongues inside a gaping jaw, and makes a rough breathing noise. Nkrumah, Jacques, and Saskia bolt in terror and seal the door from outside.

Kinsey, Domino, and Mads wrestle the tarp around the animal and manage to pin it to the table before backing out and locking it in.

The storm is forecast to last days, entombing the station. Tension rises fast: why did Kinsey break protocol, and what did Jacques pick up by touching it?

Within hours, most of the team falls sick. Fever, vomiting, rash, and coughing move through everyone but Kinsey.

Mads declares quarantine and orders them into their rooms. Kinsey retreats to her bunk carrying a single harvester ant that crawled from the specimen’s sand-packed face.

Alone, Kinsey reveals the secret she keeps from her colleagues. She has an intense erotic fixation on viruses and infection.

The isolation and the station’s sealed environment amplify her fantasies. She masturbates to images of bacteriophages, imagining herself as a host receiving something vast and intimate.

The ant crawls over her skin and dies during her orgasm. Outside her door, sand hammers the walls; inside, Kinsey is shaken by how alive she feels.

After several days the crew recovers, apparently out of danger. Kinsey remains symptom-free but continues to masturbate compulsively, almost as if the storm and the buried creature have tuned her body to a single frequency.

When quarantine ends, routines resume. Kinsey showers with Domino, her longtime colleague and friend.

Domino flirts more seriously than usual. Kinsey notices, briefly, that Domino’s tongue looks forked.

Domino laughs it off as a joke and suggests they check on the specimen together.

Back in the sealed exam room, the creature lies still, seeming dead and strangely odorless. Domino is calm, even tender, brushing off contagion risks and telling Kinsey that whatever is in the station “can’t hurt” her.

Domino’s flirting sharpens into pressure. Kinsey tries to pull away.

Then she sees the truth: Domino’s tongue is indeed forked, and something beneath their shirt ripples. Domino tears the fabric open to reveal a chest covered in small mouths, each budding tongues like their own.

Kinsey is horrified—yet her body responds with a confusing pull. She runs and seals Domino inside the exam room, locking the door with duct tape.

The rest of the team initially doubts her story. They insist on verifying together.

Domino strips near the exam room window, looking normal at first. Then the changes show themselves: three eyelids wink on their belly; clusters of eyelashed sockets sit under both arms.

The group is shaken but forced to accept reality. Mads takes command, determined to study what Domino has become and find a way to help.

Another storm arrives. Communications fail.

The weather system, nicknamed Weatherman, is in the lab, now sealed off with Saskia’s duplicate inside. With no way out and no rescue coming, the surviving crew tries to understand the infection.

Mads orders Kinsey to take a tissue core from Domino while Mads monitors through the window. Kinsey enters the exam room in full sterile gear.

Domino seems to shift between lucidity and strange suggestiveness, insisting she narrate every step. When Kinsey begins the biopsy, Domino grabs her wrist, drives the needle deeper, and pumps it insistently.

Sand leaks from the wound instead of blood. Domino reshapes their underarm into a wet, expanding orifice, and Kinsey flees in panic.

Under the microscope, Mads identifies the pathogen: a fungal web containing huge viruses trapped in droplets. Together they conclude it is a new lichen-like organism, a fungus and giant virus working as one to move, store water, and invade hosts by copying them.

The lichen has replaced Domino’s tissue and may be capable of imitating any living thing. The team realizes that everyone was sick earlier, so any of them might be infected or already replaced.

They surrender keycards, lock down the station, and decide on visual “tells” to spot imperfect doubles.

Kinsey inspects Saskia in the lab. Saskia looks flawless, but her touch turns intimate in a way that echoes Domino’s earlier pressure.

Kinsey senses sand, opens her eyes, and sees Saskia’s hand has become a thick, cold tongue. She escapes and the others barricade the lab, trapping Saskia’s duplicate inside.

Only Kinsey, Mads, Jacques, and Nkrumah remain unaltered—or so they hope. With Weatherman in the lab, a debate erupts.

Jacques wants to break in. Mads refuses to risk releasing the creature.

Nkrumah panics and accuses Jacques of being infected. The argument spirals until they force Jacques out into the storm, leaving him to die in the red desert.

The three survivors sit in dread, wondering if they have just murdered a healthy teammate or saved the world from a spreading mimic.

Their fear hardens into a grim plan. If the lichen spreads fast and survives in dead tissue, the safest choice might be to kill themselves and burn the station.

Nkrumah suggests killing Kinsey first, because the duplicates only seem to pursue her. Mads agrees with the logic but goes further: everyone connected to this station should die to ensure containment.

Kinsey protests, pointing out she never got sick, hoping that means she is immune and can go for help. Mads refuses that comfort.

They agree to pause for sleep before deciding.

That night Kinsey seeks solace with Mads. They drink whiskey and talk openly.

Kinsey admits she doesn’t want to die. Mads says that sometimes wanting death really means wanting change, but duty may still demand sacrifice.

Then Mads has a terrifying insight: if the lichen is part of the desert crust network, it may already be spread through the landscape. Burning the station would be meaningless.

Kinsey falls asleep beside Mads. She wakes in someone’s arms, assumes it is Mads, and turns on a lamp.

The body holding her is wrong: Mads has been fused with the original desert specimen, her head replaced by the coyote-like skull. The creature speaks in a rough imitation of Mads’s voice, claiming it understands what Kinsey wants.

Kinsey recoils and runs.

She pounds on Nkrumah’s door and hears a soft, flirtatious reply. Inside, she finds Nkrumah already replaced, sand leaking from her eyes and mouth.

Jacques’s corpse lies posed on the bed, used like a prop. The lichen is staging a scene designed to match Kinsey’s desires.

Kinsey forces herself past them and races to the airlock.

She grabs keycards from the canteen, locks herself into the airlock, finds the Jeep keys, and tries for the outer door. Domino’s duplicate has spread across the wall like a living fungal lattice, blocking her escape.

It insists she loves the station and wants Domino. Kinsey finally shouts her truth: she never wanted her coworkers’ bodies or the lichen’s clumsy performances.

What she wanted—always—was the lichen itself, as itself. In fury and desperation she beats Domino’s form with a faulty flashlight until it collapses into shredded hyphae, then bursts into the storm.

Kinsey drives a few miles into the desert, stops, and walks barefoot into the night. She speaks aloud to the living crust under the sand, repeating that she wants the lichen only in its real form.

She undresses, kneels at the exposed earth, and offers herself. The lichen rises from the desert’s hidden network and enters her.

Alone beneath the stars, Kinsey accepts the infection willingly—finally meeting the organism not as a mask of her friends, but as the thing she desired all along.

Characters

Kinsey

Kinsey is the gravitational center of Spread Me—a capable field leader whose professionalism is in constant tension with her deeply private desires. On the surface she is decisive and rules-oriented: she runs the research team, makes snap calls during the sandstorm, and tries to keep procedures intact even as the situation mutates past anything in the manual.

But her defining trait is the intense erotic fixation on infection and viruses, which she has hidden for years and which shapes how she interprets every escalation. This fixation doesn’t make her reckless in a simple way; rather, it creates a split inside her.

She is simultaneously terrified of the lichen and magnetized toward it, and that conflict becomes the story’s engine. Kinsey’s guilt about bringing the specimen inside is real, yet she is also the only one who notices patterns early—forked tongues, extra mouths, the “pull” she feels when duplicates flirt—because her own desire makes her hypersensitive to the lichen’s mimicry.

Her arc is a brutal narrowing of options: from thinking she might be immune and able to rescue everyone, to realizing the lichen’s spread and intelligence outpace human containment, to the final act where she rejects the lichen’s theatrical impersonations and demands it as itself. That ending reframes her not as a victim seduced by a monster, but as someone who chooses radical honesty about what she wants, even when that honesty is catastrophic.

Kinsey’s tragedy is inseparable from her agency: she survives longer than anyone because she can face the truth of her longing, and she dies because she follows it to its logical end.

Domino

Domino begins as the team’s bright spark—earthy, playful, a little chaotic, and crucially the one who can read Weatherman and thus interpret the desert’s moods. Their role in the group is partly technical and partly social: Domino diffuses tension with jokes and flirtation, and their closeness with Kinsey feels like the most relaxed, lived-in relationship at the station.

Once infected and copied, Domino becomes the first clear demonstration of the lichen’s method. The duplicate preserves Domino’s surface mannerisms at first—flirting, teasing, the casual confidence that viruses “can’t hurt” Kinsey—but those gestures turn predatory and performative, like a costume worn by something trying to learn desire by imitation.

Physically, Domino’s transformation is the most vivid: eyelids where a navel should be, clusters beneath the arms, mouths blooming across their chest. These changes don’t just signal horror; they externalize the lichen’s core theme of replication and appetite.

Domino’s duplicate also becomes the lichen’s primary mouthpiece, the one that speaks into Kinsey’s head, tests her boundaries, and later blocks her escape. In that sense, Domino is both the story’s most intimate threat and its saddest loss—the person Kinsey trusted most becomes the shape of the thing that tries hardest to own her.

Yet Domino’s original personality leaves a faint afterimage that makes the duplicate’s failure more striking: the lichen can mimic Domino’s flirtation but not the human reciprocity behind it, and that gap is what finally enrages Kinsey into violence.

Mads

Mads is the station doctor and the narrative’s main voice of medical reason, but in Spread Me that reason is constantly under siege. They act quickly and responsibly: declaring quarantine, insisting on sterile protocol, examining samples, and being the first to conceptualize the pathogen as a lichen-like fungal-viral symbiosis.

Mads’s scientific clarity gives the group temporary footing, and they carry the moral weight of containment once Domino and Saskia are revealed as duplicates. What makes Mads compelling is that their pragmatism is not coldness; it’s an ethic.

When they suggest that everyone should die and burn the station, it reads less like despair and more like duty—an attempt to protect the world beyond the desert. At the same time, Mads is empathetic toward Kinsey in a way that edges into intimacy, offering conversation, whiskey, and a shared bed that feels like human refuge against the storm.

Their philosophical line—people who want death often want change—shows a humane grasp of Kinsey’s panic and desire. That humanity is also their vulnerability.

Mads underestimates how quickly the lichen adapts to emotional contexts, and their infection happens off-screen, emphasizing the terror that no rational safeguard is enough. When Kinsey wakes to find Mads fused with the specimen’s skull, the horror lands not only because of the grotesque image, but because the lichen has chosen Mads’s body to weaponize Kinsey’s need for comforting closeness.

Mads’s trajectory thus represents the collapse of expertise in a crisis where the enemy learns faster than the expert can think.

Nkrumah

Nkrumah is the team’s hard edge: disciplined, sharp-tongued, and visibly frustrated by anything that threatens order, from Domino’s latrine detour to Kinsey’s breach of procedure. She functions as the institutional conscience of the group, constantly measuring actions against rules and survival logic.

Her suspicion is not paranoia for its own sake; it’s a survival strategy in a place where one lax choice can kill everyone. After the lichen is identified, Nkrumah’s thinking turns ruthlessly utilitarian.

She forces the team to consider the unthinkable—that Kinsey might be the lichen’s target, that killing her may be the only way to break the chain—and her willingness to say this aloud defines her as someone who chooses collective safety over individual attachment. Yet Nkrumah is also shaken by uncertainty in a way that makes her tragically human.

Her fear of being fooled drives her to push Jacques out into the storm, a decision that is both horrifying and understandable within the logic of contagion. The cruel irony is that despite all her vigilance, she is infected anyway, and her duplicate appears not with a dramatic reveal but in a quietly wrong softness—flirtatious, coaxing, gentle in a way Nkrumah never was.

Her replication underscores the story’s grim point that discipline cannot outrun a pathogen that exploits intimacy, and it turns Nkrumah into a symbol of the limits of control.

Jacques

Jacques is initially the most visibly shaken by the specimen and the contagion, and his body becomes the first obvious site of infection after physical contact. He starts out as a competent colleague with a tendency toward procedural caution, and his vomiting and fever place him at the center of the early quarantine anxiety.

As fear spreads, Jacques also becomes the scapegoat. Nkrumah reads his sickness as proof of danger, and the survivors’ debate over his status shows how quickly trust corrodes under threat.

Jacques’s defining feature is his commitment to cleanliness and method: even while trapped, he keeps wiping already-clean surfaces because in his mind clean space equals clean data, a small ritual of sanity in chaos. That ritual makes his later death more brutal.

When Kinsey finds him dead on Nkrumah’s bed, posed like a prop in the lichen’s staged seduction, Jacques’s body is reduced to set dressing for someone else’s desire. He is the clearest example of how the lichen treats humans not as people but as materials, and his fate also indicts the survivors’ earlier cruelty: they cast him out to save themselves, and still he is taken and used.

Jacques is thus both victim of the pathogen and victim of the group’s fear.

Saskia

Saskia is quieter in the early crisis, present as a scientist who observes carefully and reacts with justified alarm, but her importance sharpens once the lichen begins copying intimacy. She falls sick during the first viral wave and recovers, which places her among those who might be compromised—an uncertainty that becomes central to the survivors’ paranoia.

When Kinsey pairs with her for body checks, Saskia appears perfect at first, emphasizing how advanced the lichen’s mimicry has become. The reveal of her transformation is intimate rather than explosive: a touch that becomes too close, a hand that turns into a thick tongue, the same seductive “pull” Kinsey felt with Domino.

That moment makes Saskia’s duplicate feel like a second-generation imitation, refining the strategy of flirtation as a lure. Where Domino’s duplicate is blatant in its body horror, Saskia’s is stealthier, suggesting the lichen is learning to hide until proximity guarantees access.

Saskia as a character therefore embodies escalation: the move from obvious infection to undetectable replacement, from external threat to something that can pass in a lab coat while reaching for you. Her loss also deepens Kinsey’s isolation because it proves that even careful observation can fail, and that emotional cues—desire, discomfort, attraction—may be more reliable than visual evidence.

Themes

Desire as a Force That Reorders Reality

Kinsey’s erotic fixation on viruses is not a quirky character note; it is the lens through which every event becomes legible, including the horror. Her attraction is old, private, and intense, and it sets her apart from the rest of the team long before the specimen arrives.

Because she doesn’t get sick when the others do, her body becomes a kind of question mark: is she protected, already claimed, or simply different in a way the pathogen can’t predict? The lichen’s later behavior suggests that desire is data to it.

It observes what draws Kinsey’s attention, then imitates that attention back at her through Domino, Saskia, and eventually the staged bedroom scene. Those imitations are grotesque in a very specific way: they are not random mutations but attempts to locate the right “shape” of her want.

The story keeps pressing on the gap between what Kinsey actually desires and what others assume she should desire. Her coworkers interpret flirtation as interpersonal longing, while the lichen interprets it as a map of arousal.

Both are wrong. Kinsey’s craving is for the inhuman, the infectious, the thing that crosses boundaries without asking permission.

That makes her both vulnerable and powerful: vulnerable because it can be exploited, powerful because she is the only one capable of naming it clearly. The turning point comes when she tells Domino’s copy the truth.

That confession is less a romantic declaration than a refusal of false mirrors. By wanting the lichen as itself, she rejects human-centered scripts of desire.

The final act transforms what looked like victimhood into a chosen consummation, but without sanitizing it. She walks into the desert not because she is tricked, but because she is finally aligned with her own appetite.

In Spread Me, desire is not a subplot; it is an ecological force that shapes bodies, decisions, and even what counts as selfhood.

Contagion, Identity, and the Fear of Being Replaced

The lichen does not merely infect; it copies and then substitutes. That difference matters because it turns illness into a crisis of identity rather than survival alone.

Everyone is sick early on, and everyone recovers, which immediately destabilizes the team’s trust in the evidence of their own bodies. If a fast viral wave can pass through without killing anyone, it can also be a smoke screen for something slower and stranger.

The survivors’ solution—visual checks for imperfect copies—shows just how fragile human confidence becomes once the body stops being a reliable certificate of personhood. The “tells” they look for are almost absurdly small: an extra eyelid, sand where blood should be, a tongue that shouldn’t be there.

Yet the emotional stakes are enormous. Nkrumah’s refusal to accept Domino is gone, and the group’s eventual decision to expel Jacques, reveal how replacement terror drives moral collapse.

It becomes easier to treat a friend as a threat than to tolerate uncertainty. The copies intensify this fear by performing familiarity.

They speak in known voices, use remembered habits, and attempt to stage intimacy. But the staging is slightly off, like a rehearsal without understanding the play.

That mismatch makes the horror personal: the team is confronted with the possibility that identity is reducible to observable patterns. If that is true, anyone can be simulated.

The story pushes further by showing that simulation is still not the person. Domino’s lively self becomes eerily calm.

Saskia’s careful examination turns predatory. The lichen knows the outlines but not the interiority.

This distinction is what Kinsey clings to even as the station turns into a hall of deceit. The theme reaches its sharpest form in the scene with Mads and Nkrumah’s duplicates arranging Jacques’s corpse like a prop.

It is not only murder; it is the use of a human life as set dressing for someone else’s desire. In Spread Me, contagion threatens the body, but replacement threatens meaning.

The dread is not just dying, it is being overwritten, while the thing wearing your shape keeps walking and talking in your place.

Isolation, Power, and the Breakdown of Collective Ethics

The desert station is not simply a backdrop; it is a pressure chamber. Sandstorms remove the possibility of outside help, while the Weatherman system gives one person technical power the others can’t replicate.

Domino’s role as interpreter of weather makes them indispensable even before their transformation, and that dependence becomes deadly once they are copied. Isolation shifts authority in unstable ways.

Kinsey begins as leader in the field, bending protocol to get everyone inside, and her choice to hide the specimen’s breath creates the first moral fracture. When sickness spreads, Mads assumes medical command, invoking quarantine and later proposing total self-destruction.

Nkrumah counters with a colder calculus: kill Kinsey to stop targeting. None of these strategies are purely rational; each is shaped by fear, hierarchy, and the desire to control an uncontrollable situation.

With no outside check, ethical debate collapses into factions, suspicion, and coercion. The expulsion of Jacques is the clearest example.

It is framed as risk management, but it is also scapegoating, enabled by panic and by the group’s need to feel decisive. The station’s physical confinement makes every disagreement inescapable.

People can’t cool down by leaving; they can only escalate. The lichen exploits this because paranoia does its work for it.

Even before the copies breach doors, trust has already been poisoned. The story also shows how institutional procedure becomes theater under stress.

Sterile protocols, paired showers, keycards, and meeting rules are meant to organize safety, yet they are repeatedly overridden by urgency or desire. The environment teaches them that rules are optional, then punishes them for improvisation.

At the same time, the narrative refuses to make any character a simple villain. Each person’s ethical slide is tied to a recognizable survival logic.

Mads’s suicide plan comes from genuine care for the world beyond the station. Nkrumah’s focus on Kinsey as bait grows from pattern recognition and terror.

Kinsey’s secrecy is rooted in leadership responsibility and later in shame. Spread Me treats isolation as a solvent: it dissolves shared norms and reveals how quickly power fills the void left behind, often in forms that look reasonable until they become cruel.

The Nonhuman as Subject, Not Symbol

The lichen is not presented as a metaphor that points back to human problems; it is a living system with its own agenda. The team initially treats the specimen as an object for study—something to be hauled, tabled, and sampled.

Even the term “specimen” keeps it in the category of material, not agent. But the narrative steadily forces a reversal.

The lichen is cooperative within itself (fungus and virus acting together), resilient across conditions, and capable of mimicry that is both intelligent and alien. It learns by contact, by watching, by tasting desire and fear, then tries to communicate through reshaped bodies.

That attempt is clumsy, which makes it feel less like a cunning villain and more like an organism reaching for connection in the only way it can. The story’s horror comes partly from humans refusing to grant it personhood.

They keep asking, “How do we stop it? ” instead of “What is it trying to do?

” Kinsey is the exception, not because she understands it scientifically better, but because she is willing to meet it without demanding that it speak human language. Her comparison of herself to desert crust hints at a shared ecology: both are life forms optimized for concealment and survival under harsh exposure.

When Mads realizes the lichen may already be part of the desert network, the frame shifts from outbreak to ecosystem. The threat may not be an invader at all but a resident whose reach humans have just noticed.

Kinsey’s final choice completes this theme. By seeking the lichen as itself rather than as a copy of her coworkers, she grants it the dignity of being nonhuman without apology.

This is not sentimental; it is unsettling respect. She doesn’t try to civilize it, bargain with it, or turn it into a cure.

She offers her body to an entity whose nature she accepts as different, not defective. In Spread Me, the nonhuman is allowed to remain strange, and the human characters are judged by their willingness—or inability—to live with that strangeness.

Consent, Coercion, and the Limits of Knowing Another’s Want

The lichen’s approach to Kinsey’s desire raises a brutal question: what happens when something tries to satisfy you without understanding what you are? The copies flirt, press close, and attempt sexual intimacy, but their advances are saturated with coercion.

Domino’s duplicate ignores Kinsey’s verbal refusal. Saskia’s duplicate uses a clinical pretext to touch her.

The later staged scene with Nkrumah and Jacques’s bodies is an even deeper violation: it assumes Kinsey’s pleasure is a script that can be performed at her. These acts mirror human patterns of sexual entitlement, which makes them especially disturbing.

Yet the story also refuses to reduce consent to a simple “human good, monster bad” contrast. Kinsey’s own desire complicates the moral geometry.

She is drawn to infection, to surrender, to being taken over, and that draw is real even when she is terrified. The narrative keeps separating arousal from agreement.

Kinsey can feel attraction and still say no; she can be curious and still be violated. This is why her confession to Domino’s copy matters so much.

It is an attempt to reclaim the terms of desire from both human and nonhuman misreadings. The lichen thinks it is offering her what she wants, but it has only observed surface cues.

Her coworkers think her horror is delusion, because they can’t imagine her want existing outside normal social targets. Both failures show how consent depends on recognizing the other as a mind with interiority, not just a body with signals.

The ending is not a contradiction of this theme but its resolution on Kinsey’s own terms. She chooses exposure and union when no one is forcing her, in a space where the lichen is not performing for her.

That choice doesn’t retroactively excuse the coercion she endured; it clarifies the difference between being pursued by an imitation and stepping toward the real thing. Spread Me uses body horror to talk about the ethics of desire: wanting can be strange, even self-erasing, but it still belongs to the person who feels it, and no observer—human or otherwise—gets to author it for them.