Stag Dance Summary, Characters and Themes | Torrey Peters

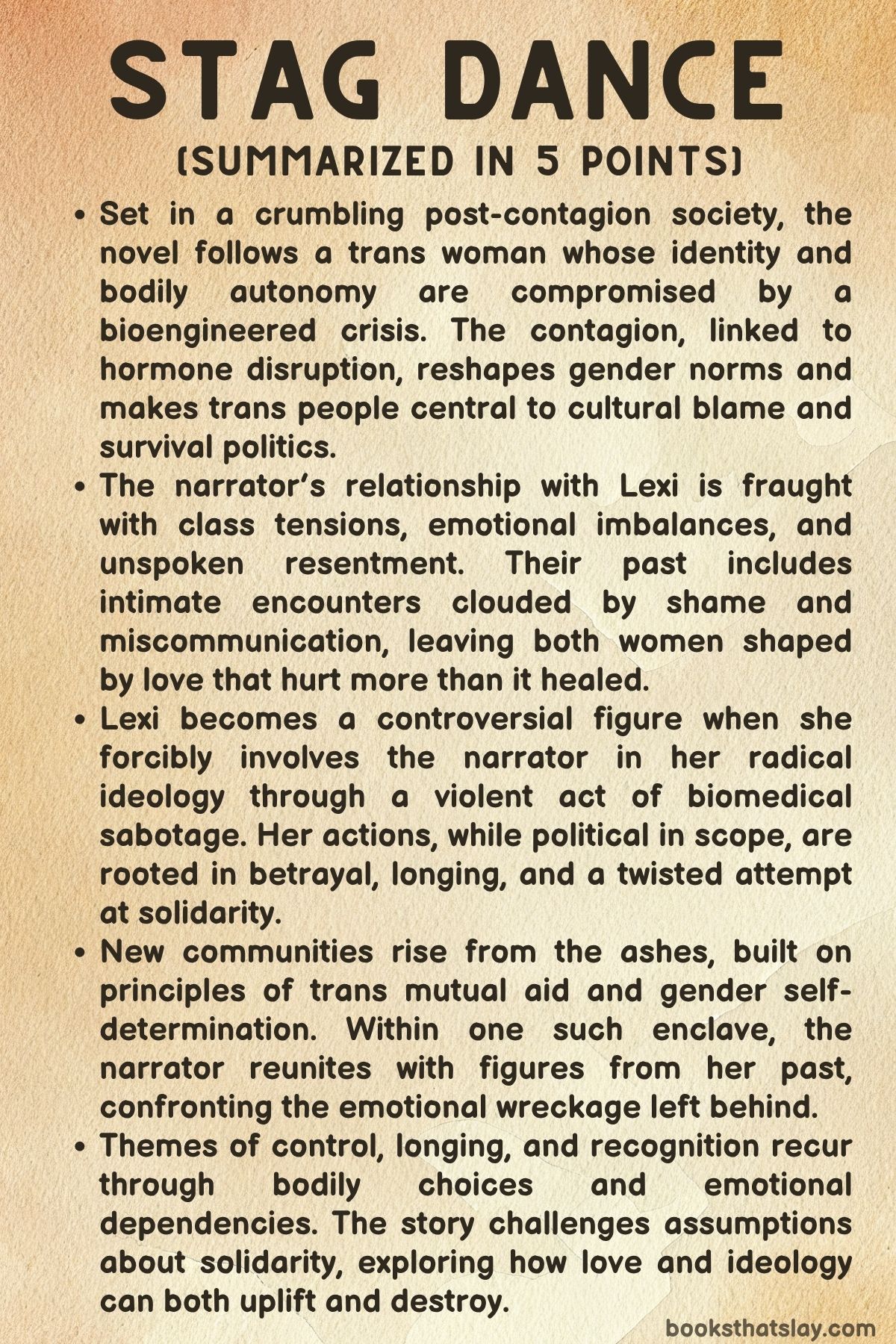

Stag Dance by Torrey Peters is a richly layered speculative novel that spans multiple timelines and environments—from a brutal logging camp in the winter wilderness to a surreal trans convention in Las Vegas, to a dystopian post-contagion society shaped by biopolitics and gender upheaval. At its heart are trans and gender-nonconforming characters negotiating love, power, survival, shame, and transformation.

The book explores what happens when intimacy and betrayal intersect with systemic violence and cultural collapse. With fierce emotional clarity, it presents a vision of queer life that is not sanitized or idealized, but raw, contradictory, often painful, and always deeply human.

Summary

Stag Dance is composed of several interlinked narratives, each centering a different character’s experience of gender, love, violence, and survival, across different speculative or metaphorically charged landscapes.

The first arc follows a gender-nonconforming narrator known as “the Babe” in a remote mountain logging camp, where isolation and harsh masculinity create both opportunity and danger. During a snowbound winter, the Babe dons a “scooch triangle,” a symbolic marker inviting courtship during the camp’s only dance.

This decision sets off a complex series of events. The Babe becomes entangled with Daglish, the timber boss, in a sexual relationship the Babe experiences as intimate but that Daglish treats as casual and utilitarian.

The emotional fallout from this disconnect opens a rift between them. Lisen, another gender-nonconforming jack who had laid prior claim to Daglish, becomes the Babe’s rival, accusing them of stealing not only Daglish but status, dignity, and feminine symbolism.

Daglish’s betrayal escalates when it’s revealed that he has informed on the camp to a timber inspector, a move that endangers them all. A drunken conflict breaks out.

In the chaos, Daglish shoots the Babe, who escapes into the forest and mountains, wounded and humiliated. The Babe’s journey becomes mythic and hallucinatory, involving mice gnawing at their wounds, memories of rejection and shame, and a final act of revenge.

When Daglish and Lisen mistake the grotesquely altered Babe for a forest spirit, the Babe uses this misidentification to their advantage and kills Daglish by toppling a tree. In a moment of symbolic retribution, the Babe takes back the torn scooch triangle from Lisen, reclaiming the identity that had been denied them.

The next narrative takes place in Las Vegas, at a convention for cross-dressers and trans women. Krys, a young cross-dresser from Iowa, arrives in search of acceptance and connection.

She meets Sally Sanslaw, a surgically transitioned older trans woman who sees herself as a mentor. Sally tries to guide Krys toward self-respect and community, but her maternalism clashes with Krys’s insecurities and hunger for validation.

Krys becomes infatuated with Felix, a charismatic and manipulative masker who presents as dominant and sexually controlling. Felix offers Krys a fantasy of acceptance and sexual desirability, but his attention quickly turns coercive and abusive.

He pushes Krys into uncomfortable boundaries, plays psychological games, and eventually isolates her from Sally. Krys finds herself emotionally ensnared, unwilling to confront the violence of the relationship because it temporarily fulfills her need for affirmation.

The climax of this section arrives when Krys, under Felix’s influence, falsely reports Sally to hotel security, leading to her arrest. Felix celebrates this betrayal, resuming his dominion over Krys, who passively accepts her new reality.

Though horrified by her own choices, Krys rationalizes her subjugation as a form of twisted love, unable to break the cycle of need and shame.

The final arc returns to the aftermath of a civilization-altering contagion caused by a hormone-disrupting vaccine. In this post-collapse world, hormone production becomes both political and weaponized.

Trans women, marginalized before the disaster, are scapegoated afterward. Among them is the unnamed narrator, who once lived in relative comfort in Seattle as a sugar baby.

Her past is tied deeply to Lexi, a rougher, survivalist trans woman she once rejected, despite their emotional and sexual entanglement.

As the contagion spreads, Lexi injects the narrator with a modified version of the vaccine, turning her into Patient Zero. This act is not merely betrayal—it is a bitter ideological statement, a punishment for the narrator’s refusal to embrace a t4t (trans-for-trans) future that Lexi envisions.

Lexi believes the future must be forged through collective suffering and forced equality. Raleen, the quiet biochemist behind the vaccine, supports the idea that destroying involuntary hormonal sex markers will create a world where everyone must actively choose gender, making the act of identification radical and egalitarian.

In the ruins of society, t4t communes emerge—enclaves where trans women who survived the vaccine gather for mutual care, political rebuilding, and spiritual healing. Lexi has become both a martyr and a demagogue.

Zoey, a survivor in one such commune, finds the narrator and brings her to Lexi. There, the narrator confronts Lexi once more.

Despite the pain—emotional, physical, and ideological—they are bound by shared history and longing. Lexi, though hardened and mythologized, still yearns for connection.

Their relationship remains full of unresolved tension. The class differences, emotional misrecognitions, and power struggles between them have left scars.

Yet the story ends not with clean resolution, but with a difficult acknowledgment of interdependence. Lexi still envisions a shared future.

The narrator, changed by betrayal and suffering, understands that to reject Lexi would also mean rejecting the only person who knew and loved her fully, even when that love was twisted.

Across all narratives, Stag Dance explores the brutalities of desire, the contradictions of trans solidarity, and the intimate violences embedded in queer relationships under pressure. From the logging camp to Las Vegas, from the apocalypse to quiet acts of caretaking, the characters search for dignity, survival, and belonging.

Their stories are raw, often painful, and deliberately unresolved, presenting gender not as identity alone, but as battlefield, theatre, and hope.

Characters

The Babe

The Babe is the central figure of Stag Dance, an emotionally turbulent, gender-nonconforming protagonist whose journey traverses environments of cruelty, humiliation, longing, and resilience. Their identity is deeply entangled with how they are perceived by others in the hyper-masculine logging camp.

Initially, they attempt to perform femininity within the constraints of a brutal world, pinning hopes on affection and acknowledgment from Daglish, only to be painfully dismissed as a transient “camp wife. ” Yet the Babe refuses to remain invisible or pitiful.

Their clever use of emotional manipulation, such as faking injury to shame the men who laughed at them, reveals an evolution into someone who begins to master the tools of power in a world dominated by force. The Babe’s physical suffering—being shot, chased, gnawed on by mice—mirrors their internal wounds, stemming from rejection, betrayal, and unmet longing.

And yet, in a climactic act of revenge, they kill Daglish and reclaim their symbolic triangle from Lisen, emerging with dignity, if not peace. They are a deeply tragic figure—mocked and mythologized, degraded and defiant, ultimately seeking more than survival: the desire to be cherished, to be named, to matter.

Daglish

Daglish is both seducer and betrayer, a man who understands survivalist performance more than emotional honesty. As a timber camp leader and arsonist with charisma and brute strength, he exploits the camp’s desperation to solidify control, framing relationships like his with the Babe as necessities rather than choices.

His calculated detachment during their sexual encounter crushes the Babe’s hopes for intimacy, reducing something meaningful to mere arrangement. Yet Daglish is not emotionally impenetrable; his reaction when threatened—violence against the Babe—suggests panic, loss of control, and perhaps guilt.

His final appearance, searching for the inspector’s trail and mistaking the Babe for a monster, reflects his inability to reckon with the emotional wreckage he caused. Ultimately, he dies beneath a falling tree—the perfect metaphor for the collapse of his control and the inescapable consequences of his exploitation.

Lisen

Lisen is as elusive and complex as she is emotionally volatile. Once the camp’s symbolic feminine figure, she becomes threatened by the Babe’s encroachment into that role, sparking a vicious confrontation laced with jealousy and longing.

Lisen’s relationship with Daglish appears rooted in both desire and power, but it’s unclear whether she ever fully possessed either. Her bitterness and her accusation that the Babe has stolen her identity and man reveal a woman both hurt and desperate to maintain status in an environment that offers so few routes to dignity.

Her tale of impersonation and seduction from youth reveals a history of gender manipulation and vulnerability. In the final moments, as she helps Daglish search for the inspector’s trail, Lisen seems to cling to fragments of meaning and control—but her final, panicked flight at the sight of the Babe indicates that she is ultimately a survivor, not a destroyer, and certainly not a redeemer.

Krys

Krys is a young, cross-dressing seeker—vulnerable, eager, and tragically misguided. She arrives at a Vegas convention full of hope, craving connection and belonging, but finds herself surrounded by older, fetishizing men and women with rigid worldviews.

Her youth and confusion make her easy prey for Felix, whose charm masks manipulation. Krys betrays her one true ally, Sally, under the pressure of wanting validation from a man who abuses her.

Her story becomes a modern tragedy of queer initiation—one that charts the costs of submission in exchange for momentary attention. By the end, Krys remains trapped, not only by Felix’s masked dominance but by her own fear of being alone.

Her complicity is heartbreaking because it’s so relatable: she chooses abuse over abandonment, clinging to degradation as if it were affection.

Sally Sanslaw

Sally is an older, surgically transitioned woman with a protective streak and a complex past as a DEA agent. She acts as a maternal figure to Krys, providing guidance and care in a world that routinely chews up the young and inexperienced.

Her strength lies in her conviction and the emotional armor she wears, honed through decades of survival. Sally sees in Krys a version of herself—someone who needs saving, mentoring, and love.

Yet her attempt to protect is ultimately met with betrayal. When Krys falsely reports her to security, Sally becomes the sacrificial lamb, punished not for her crimes but for caring too much in a world that distrusts the motives of older trans women.

Sally’s character underscores the fragility of trust and the cruel irony of being punished for offering love in a world that turns love into suspicion.

Felix

Felix is the sinister, charismatic predator in the convention segment—a figure who embodies fetishistic desire and emotional violence. He masks his toxicity behind flirtation, slowly drawing Krys into a cycle of coercion and submission.

His dominance is not just physical but psychological; he knows exactly how to manipulate the insecurities of someone craving affirmation. Through his relationship with Krys, the narrative examines how abusers often mask their intentions in the language of affection.

Felix’s cruelty is subtle, wrapped in kink and consent language that disguises emotional warfare. His masked domination at the end symbolizes the total erasure of Krys’s agency—he becomes the faceless embodiment of every man who ever said, “You’ll never do better than me.”

Robbie

In the boarding school storyline, Robbie is the narrator’s former lover turned emotional executioner. He is a paradox of vulnerability and manipulation—drawn to the narrator yet complicit in his downfall.

Their relationship is a volatile cocktail of desire, shame, and unresolved longing. Robbie refuses to clarify their final encounter to the school authorities, knowing full well his silence will damn the narrator.

Whether this is an act of self-protection or quiet vengeance is never entirely clear. He’s neither villain nor victim—just a confused, scared teenager who knows his power lies in being believed, or rather, in refusing to speak.

Robbie’s final words to the narrator, implying that everything could have been salvaged through an admission of love, encapsulate the tragic core of their dynamic: love unspoken becomes the weapon that destroys them both.

Raleen

Raleen is the quiet chemist behind the dystopian contagion in the primary narrative of Stag Dance. A trans woman herself, Raleen believes in the revolutionary potential of erasing involuntary hormone production.

Her ideology is radical—by biologically leveling the playing field, she envisions a new world where gender must be actively chosen. She is both idealist and villain, viewing her actions as necessary, if brutal.

Raleen’s guilt is not absent, but subordinated to her belief in the greater good. Her character raises haunting questions: is ethical harm permissible in pursuit of utopia?

Can betrayal be justified by ideological purity? Raleen is perhaps the most intellectually provocative figure in the novel—a portrait of the scientist as revolutionary, willing to wound her own kind in the hope of liberating them.

Lexi

Lexi is the broken prophet of Stag Dance—a trans woman turned legend, whose betrayal of the narrator (via forced infection) is simultaneously political, romantic, and deeply personal. Her ideology of t4t love becomes not only her armor but her justification for sacrifice.

She injects the narrator not out of cruelty, but out of despair, frustration, and longing. Their relationship is haunted by past class conflicts, emotional dissonance, and the aching need to be seen.

Even after years of violence and myth-making, Lexi longs for connection with the one person she felt bonded to. In the post-apocalyptic commune, she is a ghost of her former self, still fierce but emotionally raw.

Lexi’s tragedy is that she loved the narrator so much she had to destroy her—to bring her into the world Lexi envisioned, even if it meant scarring them both beyond repair. She is at once savior, monster, martyr, and lover—an embodiment of queer love stretched to its breaking point by the apocalypse.

Themes

Gender Performativity and Embodied Identity

Across Stag Dance, identity is negotiated not through declarations but through physical performance, presentation, and relational dynamics. The narrator, whether navigating a logging camp or a Las Vegas convention, finds that being seen as “real” or legitimate in gendered terms requires labor—bodily, emotional, and social.

This performance is at once necessary and treacherous. Wearing the triangle at the stag dance is not just a symbol of readiness but a public gesture that invites desire, risk, and ridicule.

The narrator’s constant tension between vulnerability and control manifests in their attempts to shape how others perceive their gender: feigning injury to avoid heavy labor, reacting violently when mocked, or yearning for affirming gazes from Daglish. In both rural and urban contexts, characters must carefully curate their gender through signs, affect, and alliances.

Lisen’s drawing, Krys’s costume, Sally’s surgeries—all are strategies of self-definition within hostile or fetishizing environments. The tragedy lies in how these gestures, often meant to secure safety or affection, open up the possibility for deeper harm.

The narrator’s eventual transformation—grotesquely altered by violence and hallucination—is both a literal and figurative mutation of gender under duress. Recognition comes, ironically, only after monstrosity has set in.

Whether in the form of the mythical Agropelter or a battered trans woman rejected by a lover, the text shows that gender is not only performed but often punished for being “too much” or “too real. ” The question of who gets to define and validate one’s embodiment remains unanswered, except in the painful currency of social betrayal or fleeting tenderness.

Power, Betrayal, and Queer Intimacy

Emotional connection in Stag Dance often operates in tandem with betrayal, creating a devastating feedback loop where affection opens the door to exploitation. The relationship between the Babe and Daglish is framed around this tension: what begins as a moment of sexual possibility quickly becomes an exercise in humiliation when Daglish trivializes their intimacy as a disposable camp-wife arrangement.

The wound inflicted is not just personal—it’s existential, challenging the narrator’s sense of self and their capacity to be desired with dignity. Lisen’s actions echo this betrayal, tearing the triangle, accusing the narrator of theft, and revealing secrets in a fit of rivalry and possessiveness.

The symbolic violence cuts as deep as the physical. Yet these betrayals do not function solely as expressions of cruelty—they are rooted in longing.

Lisen wants validation from Daglish and the camp. Daglish wants control and perhaps absolution.

The narrator wants to be wanted but not pitied. These mismatched desires clash in an ecosystem where honesty is both dangerous and rare.

In Las Vegas, betrayal takes another form. Krys’s yearning for romance becomes the vector through which Felix asserts dominance.

Her sexual awakening is not liberatory but coercive, facilitated by emotional manipulation and reinforced by gendered fetish. The ultimate betrayal—turning Sally over to security—reveals how tenuous queer solidarity can be under duress.

Intimacy, in this world, often curdles into violence because the structures to support its flourishing are absent. Queer love, when stripped of safety and affirmation, becomes both weapon and wound.

Violence as Expression and Survival

Violence in Stag Dance is not a static backdrop but a form of communication. It expresses pain, love, power, protest, and desperation, shaping every social interaction within the narrative.

The Babe’s emotional crescendo is not a cathartic confession but a tree toppled in rage and recognition. It is through a literal act of destruction—crushing Daglish—that the narrator claims agency.

Yet the act is not purely vindictive. It is the culmination of a series of dehumanizing encounters where the narrator is alternately desired, ridiculed, and erased.

Violence thus becomes a language that speaks when nothing else can. The same holds true for the camp jacks, whose drunken rampage reflects their unraveling sense of order and betrayal.

In the Las Vegas arc, violence takes a psychological and sexual form. Felix uses his mask and charm to dominate Krys, who cannot fully distinguish coercion from affection.

Her eventual submission, framed as complicity, is born of exhaustion and emotional starvation rather than consent. This creates a chilling depiction of how abuse can masquerade as intimacy, particularly when societal scripts offer no alternative.

The text does not romanticize violence but neither does it detach it from survival. The Babe’s clawing through snow, their confrontation with Lisen, the symbolic reclaiming of the triangle—all suggest that survival sometimes demands brutality.

Yet the cost of that survival is immense: disfigurement, guilt, isolation. Stag Dance forces the reader to confront how marginalized individuals use violence not only against systems but against each other when no peaceful routes are left.

Shame, Humiliation, and Emotional Exposure

Throughout Stag Dance, shame functions like a shadow—trailing each character, shifting shape, and emerging most visibly during moments of exposure. The narrator’s public injury during the blanket toss, Krys’s feelings of rejection at the convention, and Sally’s eventual arrest all reflect how quickly queer bodies can be made into spectacle.

Shame is both imposed and internalized, shaping how characters carry themselves, whom they trust, and how they interpret affection. Even small gestures—a glance, a misplaced word—become loaded with the fear of being misunderstood or mocked.

The Babe’s oscillation between pride and desperation is particularly telling: they want love from Daglish, but when that love is denied or reduced to convenience, they are not just hurt—they are made to feel foolish for wanting it. That sense of foolishness, of having dared to hope, becomes a crucible for their emotional descent.

In Krys’s storyline, shame is layered: her discomfort at being fetishized, her guilt over betraying Sally, and her confusion over wanting to be wanted by someone who sees her as a prop. Shame here is not about morality but visibility.

To be seen too clearly, to have one’s desire laid bare, is to risk devastation. And yet, the characters cannot avoid this exposure.

They are constantly negotiating their shame through small acts of rebellion or capitulation. What’s most heartbreaking is that these moments of exposure rarely yield relief.

Instead, they harden the characters, teaching them that intimacy often leads not to healing, but to another round of humiliation.

Queer Kinship and the Elusiveness of Solidarity

While the text features multiple pairings and communities, true solidarity often proves elusive. Alliances are made and broken, usually under pressure, and the idea of chosen family is undercut by competition, desire, and betrayal.

The camp jacks’ fleeting celebration of the Babe during the stag dance turns into violent scapegoating when order collapses. Lisen, who might have been a comrade-in-gender-struggle, instead becomes a rival, reflecting how proximity does not always breed empathy.

The same pattern occurs in Las Vegas: Sally attempts to mentor and protect Krys, but her older-generation sensibility and lack of boundary awareness render her vulnerable to dismissal and betrayal. The gap between their experiences—what transition meant for Sally vs.

what Krys seeks—exposes a generational divide in queer kinship that the text does not resolve. Even within a marginalized group, competing needs can corrode unity.

Solidarity, when it appears, is momentary and often transactional. Frohms helping the Babe flee, or Sally offering shelter to Krys, are brief flashes of care that cannot withstand structural or emotional pressures.

This instability underscores a bleak but honest truth: shared identity does not guarantee mutual support. What it does offer is the possibility—always tentative—of recognition.

The final exchanges between the Babe and Lisen, or Krys and Sally, suggest that even fractured relationships carry the weight of unspoken care. In that weight lies the novel’s most honest vision of kinship—not as salvation, but as a flickering, fragile effort to make meaning in a world that offers none.