Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One Summary, Characters and Themes

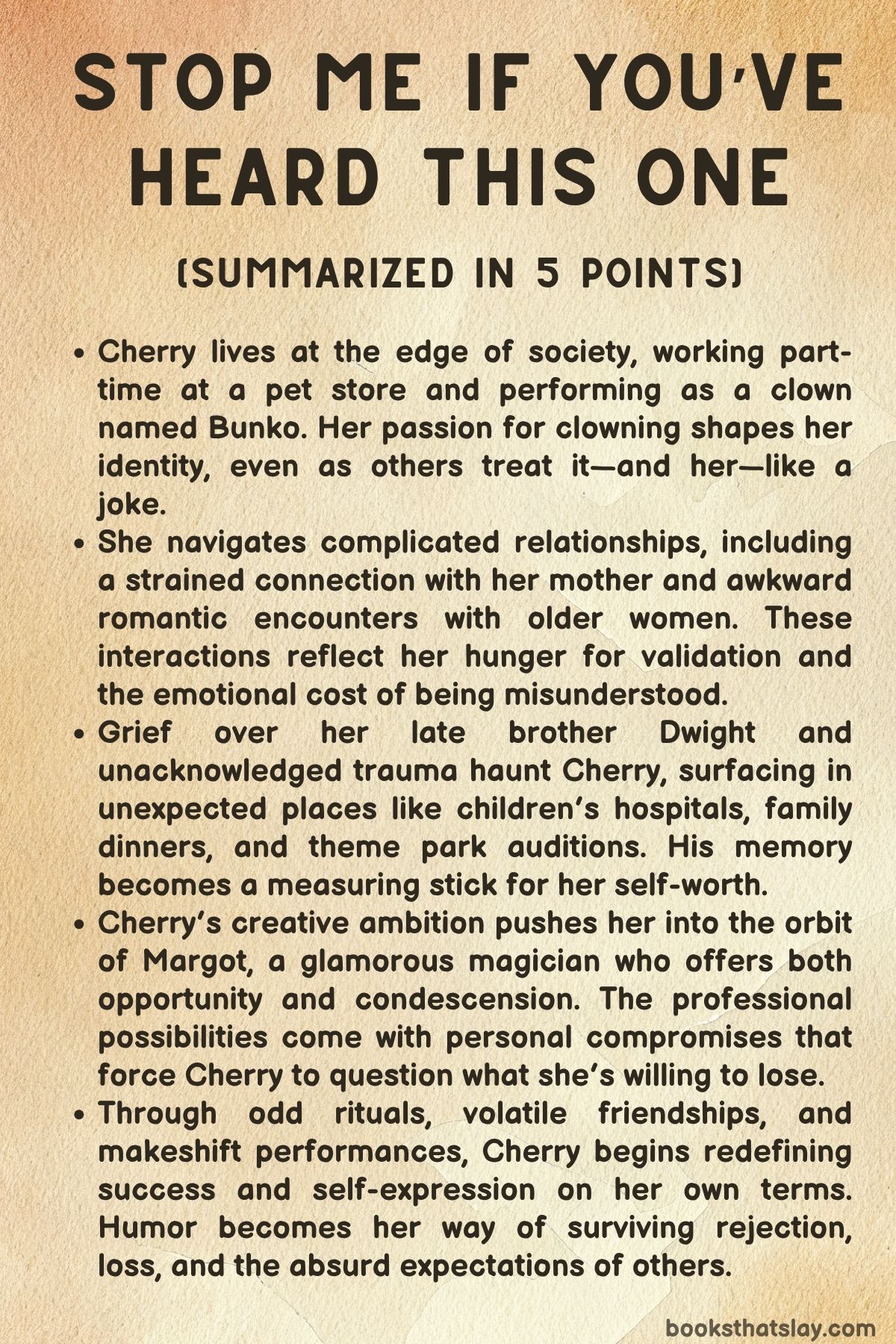

Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One by Kristen Arnett is a wild, uncompromising, and darkly humorous portrait of a queer woman trying to find meaning, love, and artistic identity through clowning in Central Florida. The novel follows Cherry, a late-twenties performer whose life is split between day jobs and her alter ego, Bunko—a rodeo clown with a fear of horses.

Cherry’s struggles are sharply drawn, exploring class tensions, familial rejection, grief, desire, and the challenge of staying true to one’s art in a world that sees her identity as either joke or threat. The story is raw, messy, surreal, and painfully sincere.

Summary

Cherry is 28, a part-time pet store employee and a professional clown living in Central Florida. She performs under the persona “Bunko,” a rodeo clown afraid of horses, and clings to her act as a form of identity and survival.

Her life is defined by contradiction: financial insecurity, queer desire, absurdity, and ambition. The book begins with Cherry performing at a child’s birthday party and engaging in a surreal, chaotic sexual encounter with the birthday child’s mother—while still in full clown makeup.

This ends disastrously when the woman’s husband walks in, prompting Cherry to flee through a bathroom window, leaving behind her entire clown kit.

Back in her day-to-day life at Aquarium Select III, she navigates the drudgery of her retail job with her punk drummer best friend Darcy and slacker coworker Wendall. The stolen clown kit is a major loss—both financially and emotionally—as it represents her artistic identity.

Cherry returns to the woman’s house to retrieve it. The encounter is humiliating, with the woman now cold and dismissive, but Cherry negotiates to reclaim her tools and some of her pride.

Cherry’s artistic aspirations reach beyond birthday parties. She longs for recognition and connection, especially from Margot, a much older magician and local performance legend.

Cherry idolizes her, hoping for mentorship or romantic interest. Their first date, however, is a disaster, marked by Cherry’s awkward jokes and Margot’s distant demeanor.

A kiss in the parking lot offers a brief moment of intimacy, but it is ultimately a goodbye, not an opening.

The novel explores Cherry’s grief over the loss of her brother, Dwight, a beloved realtor known for his ghost-themed ads. Dwight’s memory looms large—especially in contrast to Cherry’s fraught relationship with their mother, Nancy, a cold and critical lesbian who favored Dwight and finds Cherry’s lifestyle a source of embarrassment.

Cherry clings to memories of Dwight and is both haunted and driven by the question of whether he would have accepted her as she is.

Nancy begins dating again, her new girlfriend Portia destabilizing Cherry further—particularly when Cherry discovers that Portia is Margot’s ex-wife. A dinner at Nancy’s house with Portia becomes a moment of surreal cruelty when Nancy serves a peanut-laced dish, knowing Cherry’s allergy.

Cherry eats it anyway, resulting in an allergic reaction—an act that functions as both protest and cry for visibility in a household that consistently erases her.

The novel also depicts a violent incident at a local queer festival, where armed protestors attack performers and attendees. Cherry and her fellow clown Marshall attempt to protect Drag Story Hour.

The encounter leaves Marshall bloodied and traumatized, prompting him to quit clowning altogether. Cherry, shaken, sees his departure as the loss of a peer and a symbol of how fragile her community and artistic dream are in the face of escalating cultural violence.

Throughout the book, Cherry’s relationship with Darcy deepens. Darcy is often her emotional ballast, though they clash over life choices and personal direction.

Darcy’s tough love and sardonic support underscore the importance of chosen family. Their arguments and reconciliations reveal the difficulty of growing up and apart without losing love or loyalty.

Cherry is also sustained by an older mentor figure, Miri, an eccentric dollmaker and retired clown. Miri repairs Cherry’s ventriloquist dummy Velma and gives her a jumpsuit once worn by a legendary clown.

Miri represents an older generation of performers who take the craft seriously. Her gift is not only practical but an act of artistic affirmation.

When Miri dies, Cherry is left to reckon with legacy, loss, and the complex maternal surrogacy that had grown between them.

Later, Cherry performs a self-authored act called “Chuckles Bites the Dust,” in which she deconstructs and sacrifices her old persona, Bunko. The performance is raw and strange, exposing her trauma and need for validation.

It is a symbolic rebirth. She takes back control of her art, returning to her retail job still in full costume and demanding a promotion—a moment of assertive self-definition.

Margot reappears, offering Cherry a chance to collaborate on a corporate clown act. Initially hopeful, Cherry is devastated to realize she was just another auditionee.

Yet, their relationship evolves. Margot shows vulnerability, performing a strange ritual of burying dead lizards in tribute to her grandmother.

Cherry sees something real beneath the surface, though she no longer seeks Margot’s approval.

Cherry’s final transformation is not glamorous. She performs out of the trunk of her car in a gas station parking lot, combining puppetry and performance art into a chaotic but authentic spectacle.

It’s messy, weird, and entirely hers. She sleeps with Margot again, but on her own terms—refusing to build a future based on illusion or nostalgia.

In the end, Cherry doesn’t achieve stardom or acceptance from her family. What she finds instead is the quiet, potent realization that her clowning—her art, her weirdness, her history—is hers alone.

It is not a mask but a mirror. She performs for the few who stop to watch, not for approval but for expression.

She embraces her identity as both the performer and the performance, no longer seeking permission to exist. Cherry has not healed, but she is no longer hiding.

In the absurd, painful, hilarious mess of her world, she has chosen to remain visible, to keep going, and to laugh—because sometimes, that’s the only way to stay alive.

Characters

Cherry

Cherry is the beating heart of Stop Me If Youve Heard This One, a chaotic, wounded, and fiercely determined queer clown whose life is defined by contradictions. At 28, Cherry exists at the jagged edges of creative ambition and economic precarity, performing children’s parties in full clown regalia while scraping by as a part-time employee in a dingy pet store.

Her dedication to clowning is less a career and more an existential lifeline—it’s where she locates her joy, her identity, and her right to be seen. She oscillates between moments of dark hilarity and crushing vulnerability, enduring humiliation, heartbreak, and familial rejection with a kind of stubborn theatrical grace.

Cherry’s clown persona, Bunko, becomes a mirror through which she wrestles with self-worth and trauma; when she sheds Bunko in a self-eviscerating performance, it marks a raw and necessary rebirth. Her journey—through violent encounters, degrading gigs, artistic betrayal, and acts of accidental tenderness—reveals a woman who refuses to vanish, who insists on being not only seen but remembered, even if it’s through a single genuine laugh.

Nancy (Cherry’s Mother)

Nancy, Cherry’s emotionally distant and often cruel mother, represents the cold denial of queer joy and the rigid policing of identity. A stoic lesbian who favored her now-deceased son Dwight, Nancy sees Cherry’s clowning and queerness as frivolous embarrassments rather than valid expressions of selfhood.

Their interactions are fraught with passive-aggression and outright dismissal, culminating in a dinner scene that literalizes maternal neglect—Nancy serves Cherry a peanut-laced dish despite her life-threatening allergy, a symbolic act of erasure cloaked in domestic civility. Nancy’s new relationship with Portia only deepens Cherry’s sense of alienation, as it seems to underscore the possibility that her mother is capable of love—just not for her.

Nancy’s coldness isn’t one-dimensional cruelty; it’s a manifestation of generational trauma, internalized shame, and the failure to reconcile queer identity with maternal responsibility.

Darcy

Darcy is Cherry’s best friend and punk-spirited co-worker at Aquarium Select III, a drummer in a mediocre band and one of the few people who oscillate between enabling and challenging Cherry. She provides the kind of gritty, non-romantic intimacy that defines chosen family—deeply loyal, quick-witted, and unafraid to call out Cherry’s self-destructive behaviors.

Darcy represents a different form of resistance: where Cherry performs to survive, Darcy rebels to resist assimilation. Their relationship is turbulent and often hilarious, rooted in shared class struggle and queer camaraderie.

Even their arguments have an undertone of love. When Cherry begins to self-implode after the audition betrayal, Darcy becomes a mirror reflecting her back to herself—flawed, tired, but worth fighting for.

Margot

Margot is a fifty-something magician and local queer performance icon whose polished exterior conceals a deeply manipulative core. She embodies the paradox of being both mentor and saboteur, offering Cherry opportunities only to undercut her worth.

Cherry is dazzled by Margot’s glamor and theatrical mystique, misinterpreting her attention as validation. But Margot uses her position of power to manipulate, romanticize, and ultimately discard.

Even when she offers Cherry a corporate partnership, it comes with the implicit price of erasing her uniqueness for broader appeal. Yet Margot is not a simple villain; her strange lizard-burying rituals hint at a buried vulnerability.

She too has been shaped by performance, loss, and cultural invisibility. Still, her inability—or refusal—to make space for Cherry’s authenticity makes her a dangerous muse.

Dwight

Though dead, Dwight looms as a spectral presence throughout Cherry’s life. A charismatic realtor known for his ghost-themed ads, he was Nancy’s favorite, and in Cherry’s mind, the perfect child she could never be.

Cherry’s grief is complicated by resentment and longing; Dwight becomes both an unreachable ideal and a brother whose memory haunts her. His car is her sole inheritance, and his voice echoes in her thoughts as she fumbles through rejection and reinvention.

He’s a reminder of who gets to be loved unconditionally—and who gets forgotten. In Cherry’s rituals, especially in her clown acts, Dwight becomes both muse and ghost, tethering her to a version of herself that still craves approval.

Miri

Miri is the elderly clown mentor and dollmaker who offers Cherry something she’s never truly received: maternal kindness. She embodies the history and sacred lineage of clowning, taking Cherry seriously as an artist when few others do.

Miri’s home—filled with relics, dolls, and clutter—is a sanctuary of queer creativity and eccentricity. Her restoration of Cherry’s beloved dummy, Velma, and the gift of a treasured clown jumpsuit are intimate, symbolic acts of affirmation.

Miri fills the void Nancy never could. Yet, her death and the bitterness of her estranged daughter Camila expose the darker cost of artistic obsession—what is left of a mother who gives everything to her craft but not to her child?

Miri’s legacy is both a gift and a cautionary tale, urging Cherry to embrace clowning without abandoning human connection.

Camila

Camila, Miri’s daughter, appears briefly but leaves a powerful impression. Her resentment toward Cherry is sharp, born from years of being sidelined by a mother who poured her emotional energy into other artists.

Camila exposes the hidden damage behind Miri’s nurturing exterior, complicating the narrative of creative lineage. Her bitterness forces Cherry to confront the fact that being chosen by a mentor doesn’t come without consequences.

Camila serves as a reminder that familial neglect can exist even in spaces that otherwise feel affirming.

Marshall

Marshall, Cherry’s fellow clown and confidante, embodies what Cherry aspires to: resilience, popularity, and artistic confidence. His brutal injury during a violent anti-queer protest and subsequent decision to quit clowning is a psychological earthquake for Cherry.

It forces her to face the fragility of their shared art in a society that views queerness as a threat. Marshall’s departure is more than a personal loss—it signals the collapse of a safe, if precarious, creative world.

His absence leaves Cherry to decide whether she will also walk away—or risk everything to continue.

Portia

Portia is Nancy’s new partner and, in a surreal twist, the ex-wife of Margot. Her presence is deeply unsettling for Cherry—not only does she symbolize her mother’s capacity to love someone else, but her connection to Margot further tightens the web of personal betrayals.

Portia’s culinary choices nearly kill Cherry, an act that reads as a passive-aggressive assault cloaked in domestic hospitality. Yet Portia remains oblivious, a character who, while not directly antagonistic, embodies the kind of quiet violence that comes from being seen only partially—never fully, never safely.

Lauren

Lauren is a younger, vibrant clown-auditioner whose glittered, contortionist performance encapsulates everything Cherry feels she is not—agile, fresh, and visually magnetic. Her kindness toward Cherry during the audition is genuine, but it only deepens Cherry’s sense of inadequacy.

Lauren isn’t cruel or manipulative; rather, she serves as a painful reflection of the industry’s changing standards. She underscores the shifting metrics of worth in performance art, where humor and depth are increasingly displaced by spectacle.

Velma

Velma, Cherry’s ventriloquist dummy, is both prop and emotional talisman. Restored by Miri and rediscovered after her death, Velma becomes the centerpiece of Cherry’s final act.

Through Velma, Cherry stages a grotesque courtroom drama that allegorizes her artistic struggle. Velma speaks the words Cherry cannot, testifies to pain Cherry cannot name.

The dummy becomes a repository of grief, rage, and redemption. In reclaiming Velma, Cherry reclaims herself—not as a silent joke, but as a performer with something vital to say.

Themes

Queer Identity and Performative Survival

Cherry’s existence is framed by a constant negotiation between who she is and how she is perceived, particularly through the lens of her queerness and clown identity. These two layers—queer woman and clown—merge into a singular form of survival, not merely performance.

She is both visible and invisible, eroticized and discarded, celebrated and ridiculed. Her clown persona, Bunko, becomes a vehicle through which she can express herself without immediate personal risk, but the boundary between Cherry and Bunko remains porous.

This creates a psychological tension where Cherry is both empowered by her performance and made more vulnerable by it. The transactional sexual encounter at the beginning is emblematic of this contradiction—Cherry is desired not for herself but for the caricature she becomes, and once that illusion shatters, she is disposable.

Public space, too, becomes a battleground for her identity, where homophobia erupts even during something as innocuous as face painting at a family festival. Her queerness is treated as both spectacle and threat, and yet Cherry refuses to abandon it.

Instead, she embodies it more insistently, finding brief sanctuaries in queer venues and chosen kinships. The entire narrative becomes a study in how queer identity often demands both artistic performance and emotional concealment, a balancing act that Cherry navigates with wit and painful honesty.

Her decision to remain in clowning, despite its stigma and danger, signals a radical commitment to live authentically even when authenticity invites mockery or violence.

Familial Rejection and the Longing for Recognition

The relationship between Cherry and her mother operates on a simmering undercurrent of disapproval, disappointment, and unmet expectations. While both women share queer identities, they are utterly disconnected in their experiences and expressions of that queerness.

Cherry’s mother, Nancy, idealizes her deceased son Dwight and seems unable or unwilling to extend that same love to Cherry. Dwight’s memory becomes a barometer against which Cherry is relentlessly measured and consistently found lacking.

This familial imbalance fuels Cherry’s need for validation—not just artistically, but personally. The dinner scene, where Nancy prioritizes Portia’s peanut-laden casserole over Cherry’s safety, functions as a literal and symbolic rejection.

Even in a moment of medical emergency, Nancy remains emotionally distant, caring more about etiquette than her daughter’s well-being. Cherry’s deliberate decision to eat the dish feels like an act of self-harm born out of a desperate need to be seen and remembered, even if it’s through trauma.

This yearning for maternal recognition is never resolved, and that absence becomes a psychological bruise Cherry continually presses. Her grief over Dwight is tangled with resentment, not toward him, but toward the way his memory consumes all available familial love.

Through all of this, Cherry’s attempts to build a chosen family—particularly with Darcy and Miri—emerge as compensatory gestures to fill the void left by maternal indifference. Yet even those relationships carry echoes of the same struggle for approval, making recognition—both emotional and artistic—a central driving force of Cherry’s internal life.

Artistic Integrity versus Economic Survival

Cherry’s clowning is more than a job; it is her artistic and spiritual calling. But that calling is constantly under siege by financial desperation, capitalist structures, and shifting cultural tastes.

The tension between art and commerce manifests throughout the narrative—whether she’s scrubbing fish tanks for minimum wage, bartering her clown kit for cash, or contemplating a theme park partnership that could offer security at the cost of creative freedom. Margot’s manipulative audition invitation further highlights how the illusion of opportunity can mask exploitation.

Even within the clown community, there’s a hierarchy—Marshall, more successful and better connected, exits the field after a traumatic event, leaving Cherry to question whether resilience is sustainable in the long term. Her act “Chuckles Bites the Dust” becomes a crucible where these anxieties crystallize into something grotesquely cathartic.

It is not just performance but an autopsy of her own creative spirit—funny, painful, absurd, and brutal. Here, Cherry sacrifices her past self, the persona of Bunko, to reclaim her autonomy and rebuild her art on her own terms.

She doesn’t reject commercial opportunities outright but insists on retaining control over her voice. Even her final acts—performing in parking lots, confronting Margot with clarity—are not born out of desperation but choice.

In this way, Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One explores how the pursuit of artistic integrity is not about rejecting money, but about refusing to commodify the self into something unrecognizable.

Grief as Companion and Creative Catalyst

Dwight’s death lingers over every decision Cherry makes, not as a distant memory but as an ever-present ghost. His image—handsome, funny, charismatic—becomes both comfort and competition.

While Cherry wrestles with the grief of losing a brother, she also contends with the shadow his perfection casts over her identity. Her refusal to visit his grave, her obsessive consumption of articles about him, and her frequent imagined conversations with him all reflect how unresolved grief functions as both anchor and propulsion.

Dwight represents what Cherry believes she can never be: loved without condition, publicly cherished, and effortlessly successful. His ghost simultaneously haunts her insecurities and fuels her creative drive.

She wants to be funny enough, visible enough, memorable enough—for someone to laugh and not forget her. Grief becomes a creative force in this narrative, pushing Cherry to perform, to invent, to demand space in a world that has already mourned her in advance by refusing to take her seriously.

When she visits Miri’s home after her mentor’s death, grief takes on another dimension: legacy. Miri, in pouring more of herself into her art and mentees than her own family, mirrors Cherry’s own sacrifices.

Through these mirrored losses, Cherry comes to see grief not just as absence, but as continuity. It is a weight she carries not to be rid of, but to give form to her performances.

In laughter, she does not banish grief; she invites it to sit beside her, red nose and all.

Chosen Family and Emotional Resilience

In a world that often meets her with violence, mockery, and disinterest, Cherry clings to the emotional lifeline offered by chosen family. Her friendship with Darcy is jagged but vital, built on sarcasm, shared hardship, and mutual accountability.

They fight, withdraw, reconnect—each moment layered with the deep intimacy of friends who know both the best and worst in each other. Darcy functions as both cheerleader and critic, someone who will call Cherry out while still bailing her out.

Their scenes together, particularly the absurd yet tender car reconciliation, embody the strange but sustaining dynamics of platonic queer love. Miri, too, occupies a maternal space that Cherry’s own mother never could.

The clown matriarch not only repairs Cherry’s doll but also affirms her as an artist and heir. Her death, and the revelation of her fraught relationship with her own daughter, serve as a reminder that familial bonds are often made, not inherited.

Even the audience Cherry garners at a convenience store parking lot—strangers who stop, laugh, and move on—represent moments of connection forged through performance. In each of these relationships, Cherry finds partial healing.

While no bond is perfect or permanent, they offer respite from isolation. The resilience she develops is not born of internal fortitude alone, but of these brief yet meaningful intersections with others who see her not as a freak or failure, but as fully human.

Through these connections, Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One offers a defiant counter-narrative: survival is not solitary, and laughter, even shared among outcasts, is a kind of communion.