Story of a Murder Summary and Analysis

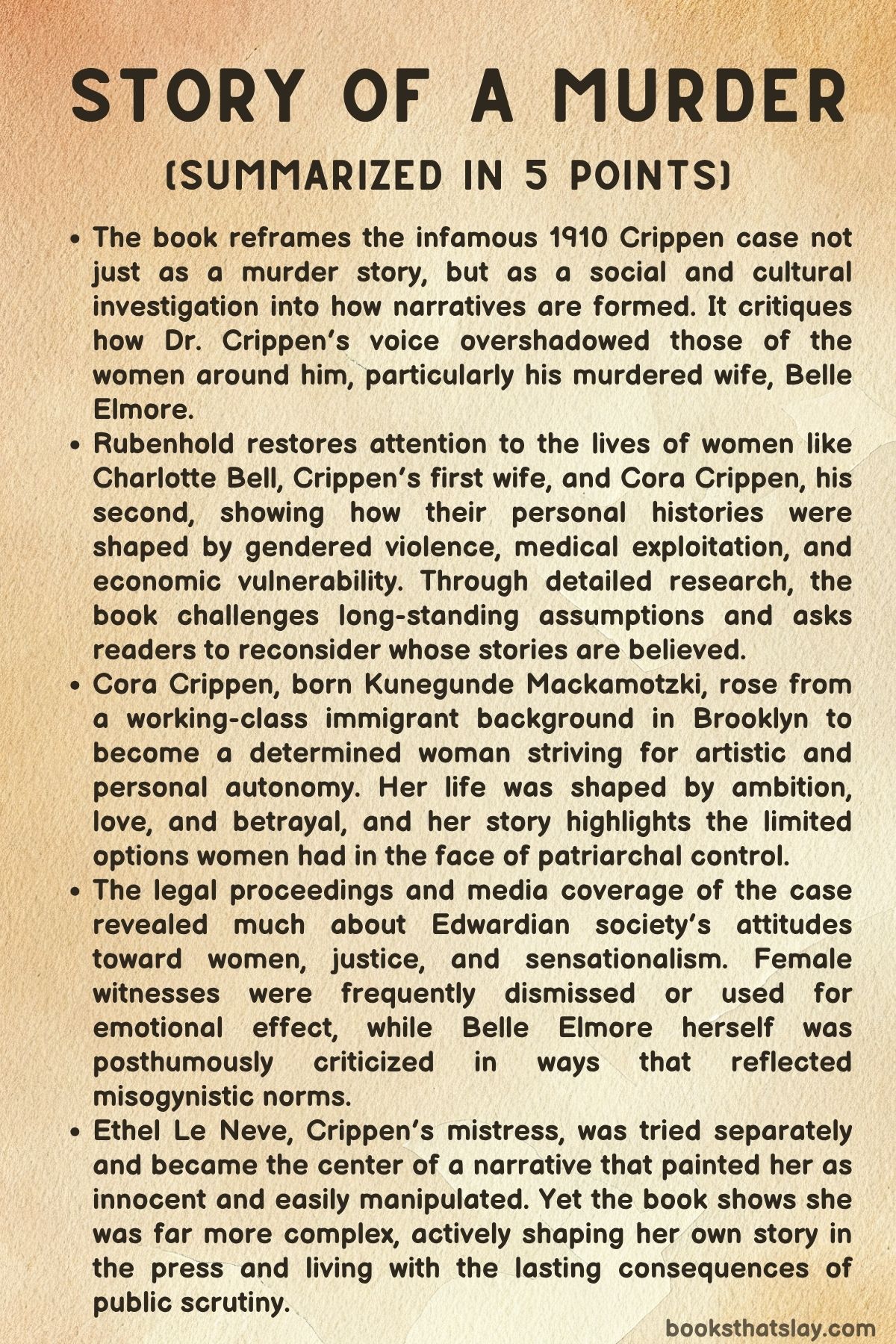

Story of a Murder by Hallie Rubenhold is not merely a retelling of the infamous 1910 murder of Cora Crippen by her husband, Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen.

It is a thorough, historically grounded reexamination of how women—particularly Cora and Crippen’s first wife, Charlotte—have been silenced, overlooked, and vilified in the public narrative surrounding the case. By shifting the lens from the murderer to the women whose lives were shaped and ultimately destroyed by him, Rubenhold dismantles decades of sensationalist myth and male-centered storytelling. This book is as much about the crime as it is about society’s treatment of female agency, identity, and justice in Edwardian England and beyond.

Summary

The story begins by confronting the long-standing imbalance in how the 1910 murder of Cora Crippen has been framed. Traditionally, the tale centers on her husband, Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen—a mild-mannered homeopath turned murderer whose composed demeanor and strategic lies made him the default narrator in both police accounts and the public imagination. Hallie Rubenhold challenges this framing by re-centering the narrative on the women involved, especially Cora Crippen and Charlotte Bell, Crippen’s first wife.

These women, often caricatured or erased in previous versions of the story, are given depth, history, and voice through meticulous archival research.

Charlotte Bell’s life unfolds against the backdrop of a declining Irish Protestant family. Born into a genteel household that gradually slid into poverty, Charlotte trained as a nurse in New York and met Crippen while working at a homeopathic hospital.

They married quickly, but the relationship turned abusive. Charlotte’s death at thirty-three was officially attributed to a stroke, but posthumous suspicions—bruises, coerced medical interventions, and Crippen’s odd behavior—suggest the possibility of foul play.

Although her death went uninvestigated at the time, Rubenhold treats it as the beginning of a dangerous pattern.

The book then turns to the life of Kunegunde Mackamotzki, later known as Cora Crippen. She was born in Brooklyn to working-class immigrant parents and raised in a tightly-knit, loving household.

Her family, despite economic hardship, nurtured her talents—particularly her musical skills. A bright and ambitious teenager, Cora received an education and studied languages, eventually working as a governess.

She became involved in a scandalous relationship with her employer, Charles Cushing Lincoln, and underwent a secret abortion—likely performed by Dr. Crippen or under his supervision.

This episode initiated her relationship with Crippen, and they married in secret soon afterward.

Their early marriage held promise, especially when Crippen secured a prestigious academic role in Louisville, Kentucky. However, his inability to maintain professional discipline led to the collapse of this opportunity.

The couple drifted to St. Louis, where Cora found fleeting happiness in modest domestic life.

She embraced her identity as Mrs. Crippen and gained admiration for her singing.

Crippen, meanwhile, floundered in a series of medical and commercial ventures. Back in New York, they lived with Cora’s family, spinning falsehoods about their background.

Crippen’s evasiveness raised suspicions, particularly about his first marriage and his son, Otto, whom he kept hidden from Cora’s family.

One of the most traumatic moments in Cora’s life was the forced ovariotomy orchestrated by Crippen. He justified the surgery as medically necessary, but Cora’s family suspected it was driven by his refusal to father more children.

The procedure, which rendered her sterile, left her emotionally and physically devastated. Even so, Cora returned to music, training for Grand Opera.

Her career, however, stalled under the weight of social expectation, physical transformation, and a deteriorating marriage. Crippen’s interest in her had waned; he shifted focus to commercial medicine and to his growing relationship with his secretary, Ethel Le Neve.

As Crippen became increasingly absorbed in his affair with Ethel, tensions in the Crippen household escalated. Cora, known to the public as Belle Elmore, remained socially active and deeply connected to the Music Hall community.

Her allies in the Music Hall Ladies’ Guild began noticing her absence in 1910 and pressured Crippen for information. He claimed she had returned to America, a story riddled with inconsistencies.

Eventually, Cora’s friends reported their concerns to the police.

Inspector Dew led the investigation and searched the Crippens’ home, initially finding no evidence. Crippen fled with Ethel, disguised as a boy, and the discovery of human remains beneath the basement floor followed shortly after.

Forensic experts confirmed the remains belonged to a woman and bore evidence of surgical scarring that matched Cora’s history. A chemical analysis also revealed traces of hyoscine hydrobromide, a drug Crippen had recently purchased.

The couple’s flight led them aboard the Montrose, bound for Canada. Captain Henry Kendall, recognizing the fugitives from newspaper reports, signaled British authorities via the ship’s new wireless telegraph system.

This allowed Inspector Dew to intercept them in Quebec. Their dramatic capture became one of the first high-profile criminal cases involving wireless communication, adding technological intrigue to public interest.

Crippen’s trial, beginning in October 1910, drew mass attention. The prosecution, led by Richard Muir, framed Crippen as a cold, manipulative killer who murdered his wife for financial and romantic gain.

The defense tried to rehabilitate Crippen’s image and vilify Belle Elmore by attacking her character. Scientific evidence, particularly forensic testimony by Augustus Pepper and Bernard Spilsbury, was critical in securing a conviction.

The presence of a surgical scar and the identified poison in the remains countered defense arguments and left the jury little room for doubt.

Crippen’s composed testimony failed to persuade. He denied all wrongdoing and claimed the remains were not Cora’s, but inconsistencies and his behavior during the investigation undermined his credibility.

The jury found him guilty, and he was sentenced to death. He never confessed and went to the gallows insisting on his innocence.

Ethel Le Neve was tried separately for being an accessory after the fact. Although she had withdrawn money from Belle’s account and fled with Crippen, the prosecution could not definitively prove her complicity.

Her defense counsel, F. E. Smith, employed the “Svengali defense,” portraying her as an innocent young woman manipulated by a dominant older man. The all-male jury acquitted her swiftly.

In the years that followed, Ethel lived a life marked by emotional turmoil and secrecy. She moved to Canada briefly, suffered from paranoia and breakdowns, and eventually returned to England under a new identity.

She married and raised children who remained unaware of her past. The real Ethel, assertive and ambitious, was a far cry from the meek image presented in court.

The book also critiques the public’s and media’s portrayal of Belle Elmore. She was often caricatured as vain, loud, and difficult—qualities that made her an unsympathetic victim in the public eye.

This demonization reflected broader cultural discomfort with assertive, independent women. By contrast, Crippen was sometimes seen as the “wronged husband,” a narrative supported by the sexist and classist biases of the time.

In Story of a Murder, Rubenhold reconstructs the lives of the women erased or diminished by history. She interrogates the archives, challenges the narratives shaped by patriarchal systems, and restores the complexity of the women behind the sensational headlines.

The book offers a portrait not only of a notorious crime but of the culture that shaped its telling.

Characters

Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen

Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen is a deeply unsettling and complex figure whose seemingly gentle demeanor masks a pattern of coercion, deceit, and potential serial abuse.

Though outwardly presenting as a mild-mannered, soft-spoken homeopathic doctor, Crippen exerts control over the women in his life through emotional manipulation, strategic omissions, and, as suggested by both Charlotte Bell’s and Belle Elmore’s experiences, medically facilitated violence. His relationships are marked by a disturbing desire to mold women’s bodies and choices to suit his own ambitions—compelling sterilizing procedures, suppressing reproductive autonomy, and gaslighting their emotional responses.

Professionally, he moves through a series of failed opportunities, driven by a desperation for prestige but lacking the integrity or competence to sustain legitimate positions. Crippen’s methodical calm, even under duress, allows him to narrate and dominate the story of his wife’s disappearance until scrutinized by forensic evidence.

His trial performance—logical but emotionless—only heightens suspicion, suggesting a man more invested in maintaining control of his narrative than expressing genuine grief or remorse. Even in his final days, he refuses to confess, instead clinging to a persona of misunderstood civility.

Crippen embodies the darker edges of Edwardian masculinity—seemingly benign yet dangerously entitled, always asserting authority over women’s lives, bodies, and voices.

Charlotte Bell

Charlotte Bell, Crippen’s first wife, emerges as a quietly tragic figure whose life trajectory is shaped by the fading fortunes of Irish Protestant gentry and the hardships of immigration. Intelligent, educated, and dignified, Charlotte is a woman shaped by personal loss and economic necessity.

Her marriage to Crippen begins with hope but gradually devolves into emotional and physical suffering. The narrative implies a deeply abusive relationship, where Charlotte not only endures Crippen’s financial instability but also his coercive control and medical violence.

Testimonies from her brother and neighbors hint at beatings, emotional torment, and potentially fatal mistreatment masked as medical care. Her death, officially deemed a stroke, is laced with ambiguity—her bruised body, the rushed burial, and Crippen’s detached behavior suggest a sinister pattern that would repeat itself.

Charlotte’s story is not only vital to understanding Crippen’s pathology but also a chilling reminder of how women’s pain could be easily buried—both literally and metaphorically—in a time when male authority in medicine and marriage went largely unchecked.

Cora Crippen (Belle Elmore)

Cora Crippen, born Kunegunde Mackamotzki and later known as Belle Elmore, is a vibrant and complex woman whose transformation from a working-class immigrant child to a vaudeville performer encapsulates both resilience and tragedy. Raised in a multilingual, multicultural Brooklyn neighborhood, she is shaped by poverty but emboldened by a supportive family that nurtures her musical talent and independent spirit.

Her early adulthood is marked by scandal and heartbreak, particularly a secret pregnancy that leads to an abortion—likely overseen by Crippen himself—thus binding her fate to a man whose ambitions would ultimately destroy her. As a wife, Cora is dynamic, assertive, and socially magnetic, often the more successful of the pair.

However, she is subjected to Crippen’s controlling tendencies, most disturbingly through a forced ovariotomy that irreparably alters her health and identity. Her passion for performance remains a defining feature throughout her life, offering a sense of purpose even as her marriage unravels.

Yet, society’s judgment of her character—as loud, demanding, and sexually autonomous—makes her an easy target for public scorn, especially after her disappearance. Her murder is not just an act of domestic violence, but a cultural erasure, silencing a woman whose existence challenged Edwardian ideals of femininity, obedience, and propriety.

In this retelling, Belle’s voice—though forever lost—is reconstructed with dignity, depth, and agency.

Ethel Le Neve

Ethel Le Neve is perhaps the most enigmatic figure in this narrative—a woman simultaneously painted as victim, accomplice, and survivor. Publicly, she was exonerated by a legal defense that leaned heavily on gender stereotypes, portraying her as an innocent young woman seduced and controlled by Crippen.

This defense—a “Svengali narrative”—emphasized fragility and helplessness, drawing upon Edwardian fears of modern womanhood to secure her acquittal. Yet, the real Ethel was anything but passive.

In the years following the trial, she displayed tenacity and strategic thinking, selling her story, lobbying for Crippen’s appeal, and carefully managing her public image. Her ghostwritten memoirs reveal a woman who was emotionally dependent on Crippen but far from powerless.

After the trial, Ethel’s life was marked by mental instability, secrecy, and reinvention. Living under an assumed name, she married and had children while maintaining a guarded emotional distance.

Her past haunted her, surfacing through dissociative episodes and a constant fear of exposure. Ethel’s dual identity—publicly innocent yet privately burdened with moral ambiguity—highlights the complexities of female agency in a patriarchal society.

She was both shaped by the social constraints of her time and subversive in her refusal to remain fully silenced.

The Music Hall Ladies’ Guild (Clara Martinetti, Melinda May, Louise Smythson)

These women collectively serve as a powerful counterforce to the dominant male narratives that initially shaped public and legal perceptions of the Crippen case. As members of the Music Hall Ladies’ Guild, Clara Martinetti, Melinda May, and Louise Smythson occupy a rare space in Edwardian society—women who not only perform in the public eye but who leverage their communal ties and public platform to seek justice.

Their testimony during the trial is emotionally grueling yet unrelenting, demonstrating a rare collective commitment to vindicating Belle Elmore’s memory. They are systematically underestimated and dismissed by the authorities, who view their emotional responses as hysteria or dramatics, but the consistency of their accounts and the bravery they exhibit in the courtroom challenge these assumptions.

These women exemplify a solidarity that transcends entertainment, illustrating how female networks operated within and against the margins of respectability to protect one of their own. Their courage under legal and social pressure reasserts the validity of female testimony in an age that frequently silenced or diminished it.

Richard Muir and Bernard Spilsbury

Though peripheral in terms of personal development, Richard Muir and Bernard Spilsbury represent critical forces within the machinery of Edwardian justice. Muir, as the Crown prosecutor, is methodical, eloquent, and incisive in his cross-examinations.

His ability to dismantle the defense’s narrative and expose contradictions in Crippen’s account reflects a sharp legal mind attuned to both forensic and emotional persuasion. Meanwhile, Spilsbury, the pioneering forensic pathologist, embodies the rising influence of science in criminal justice.

His careful, clinical testimony about the dismembered remains discovered in Crippen’s cellar, and his authoritative conclusions, lend credibility to the case and symbolize the shift toward scientific modernity in the courtroom. Together, they underscore how the Crippen trial was not only a matter of law but a showcase for new methods of establishing truth—ones that would shape public perceptions of crime for generations.

Belle Elmore’s Family

Cora’s family—particularly her mother and stepfather—form the emotional backbone of her early narrative. Supportive, pragmatic, and enduring, they foster Cora’s talents while navigating the uncertainties of immigrant life in Brooklyn.

Her stepfather, Frederick, is especially influential in nurturing her musical gift, representing the kind of masculine support she would tragically lack in her adult relationships. As the story unfolds, their growing distrust of Crippen—rooted in his secrecy, manipulation, and cruelty—serves as a powerful counter-narrative to his self-fashioned image of geniality.

Their inability to intervene in time becomes one of the many quiet tragedies within the broader story, a reminder of how families could be sidelined or silenced by patriarchal medical authority and social convention.

The Jury and Edwardian Society

Though not individuals per se, the all-male jury and the broader Edwardian public play a decisive role in shaping the case’s outcome and its cultural resonance. The jury’s susceptibility to gendered stereotypes and moralizing narratives—vilifying Belle while sympathizing with Ethel—reflects a society deeply uncomfortable with assertive women.

The media spectacle surrounding the trial, filled with voyeurism, exoticism, and class prejudice, transforms the case into a national obsession, one that reinforces and projects collective anxieties about shifting gender roles. The trial becomes not just a question of guilt but a referendum on womanhood itself: who deserves sympathy, who warrants scorn, and who has the right to speak.

Their judgments—both legal and cultural—linger far beyond the courtroom, shaping public memory and obscuring the humanity of the very woman whose murder initiated the drama.

Themes

Gender, Power, and Historical Erasure

In Story of a Murder, gendered power dynamics shape the architecture of both historical record and legal process. The women at the center of the narrative—Charlotte Bell, Belle Elmore (Cora Crippen), and Ethel Le Neve—are each, in different ways, silenced, marginalized, or reshaped by the men and institutions around them.

What emerges is not just a story about male violence, but a chilling portrait of how female voices are systematically excluded from the construction of memory and justice. Belle’s own murder renders her permanently voiceless, yet her absence is then exploited by others—most notably Crippen himself—to spin a self-serving story that minimizes her humanity.

The press and the courts collude in this erasure, choosing to amplify Crippen’s version of events while depicting Belle in demeaning, stereotypical terms: vain, loud, or overbearing. Meanwhile, Ethel Le Neve is subjected to the opposite distortion.

Her agency is deliberately stripped away by a legal defense that frames her as helpless and manipulable in order to exonerate her. These manipulations reflect a broader Edwardian anxiety around the increasing visibility of independent women.

The Music Hall Ladies’ Guild, whose female members take the stand in Crippen’s trial, challenge this cultural silencing by asserting their authority as witnesses and community figures, though their testimonies are emotionally drained and constantly questioned. The book refuses to accept these distortions, instead offering a corrective by examining private letters, community records, and the broader social texture that shaped the women’s lives.

Through this, it insists on restoring presence and dignity to women who were denied both in life and death.

Social Class and the Illusion of Upward Mobility

Class tension is an undercurrent that shapes nearly every life decision in Story of a Murder, particularly through the lens of Charlotte Bell’s descent and Cora Crippen’s striving ascent. Charlotte begins life as part of a once-prosperous Protestant Irish family, only to see that status dissolve through debt and historical circumstance.

Her relocation to the United States, her training in nursing, and her subsequent marriage to Crippen reflect the desperation and resourcefulness of a woman trying to reestablish herself in a society that no longer guarantees her protection or dignity. Cora, by contrast, is born into poverty in Brooklyn but nurtures dreams of performance, elegance, and social elevation.

Her reinvention—from Kunegunde Mackamotzki to Belle Elmore—is an act of self-fashioning, a strategy to escape the limits placed on immigrant women. Yet both women find that these aspirations collide with entrenched hierarchies and patriarchal violence.

Crippen, who himself seeks validation through professional and romantic conquests, repeatedly undermines their efforts, acting not just as a violent man but as a symbol of structural betrayal. He uses medical authority to control their reproductive futures, manipulates their ambitions for his own comfort, and denies them access to social legitimacy.

The narrative lays bare how women’s attempts at mobility are constantly curtailed—by financial precarity, institutional bias, and the capricious behavior of the men they depend upon. The story becomes not only a portrait of failed marriages but also an indictment of a society that dangles the promise of social ascent while ensuring it remains out of reach for those who don’t meet its male and class-bound standards.

Medicine, Control, and the Female Body

Medical authority is not a neutral force in Story of a Murder, but a tool of control, especially over female bodies. Both Charlotte Bell and Cora Crippen are subjected to medical interventions that reveal more about Crippen’s desire for domination than about any genuine concern for their well-being.

Charlotte’s experience with suspected abortions and unexplained physical decline hints at coercive reproductive manipulation. Meanwhile, Cora’s forced ovariotomy—a surgery that sterilizes her under the guise of health—is devastating in both its physical consequences and its symbolic weight.

Performed without her full consent, likely at Crippen’s insistence, the operation severs her from any future as a mother and accelerates her physical decline. The narrative uses these moments to highlight how medicine, particularly when wielded by male practitioners, becomes a site of gendered violence.

Crippen’s dual identity as a doctor and an abuser embodies this convergence of knowledge and power. The legal system, too, relies on medical testimony to make or break the case, but often with contradictory results.

While expert witnesses help secure Crippen’s conviction by identifying surgical scars and poisons, earlier interventions went unquestioned or unpunished. The broader implication is that medicine, while cloaked in objectivity, is deeply shaped by the prejudices of its practitioners and the era’s cultural assumptions.

Women’s pain is ignored, their autonomy disregarded, and their bodies reshaped to fit male priorities. This theme forces the reader to reckon with the hidden abuses embedded in professional authority and the long-term consequences of decisions made without women’s full participation or understanding.

Performance, Spectacle, and Public Narrative

Publicity and spectacle are omnipresent forces in Story of a Murder, shaping not only the legal proceedings but also the social lives of its central characters. Cora, as a vaudeville performer and aspiring opera singer, understands the power of performance.

Her life becomes a balancing act between public persona and private suffering, especially as her musical aspirations offer both a sense of identity and a fragile claim to respectability. Crippen’s trial becomes the ultimate spectacle, attracting crowds, celebrities, and global media attention.

The courtroom itself is transformed into a stage, with lawyers and witnesses performing roles designed to sway an audience as much as to uncover truth. Even forensic science, which should function as objective analysis, becomes part of this theater.

The press plays a pivotal role in turning Belle into a caricature, Ethel into a tragic ingénue, and Crippen into a monstrous yet fascinating antihero. These constructed narratives quickly harden into public memory, obliterating nuance and erasing contradictions.

The reader is reminded that justice, when filtered through the needs of performance, is vulnerable to distortion. Ethel’s post-trial reinvention—her name change, her ghostwritten memoir, her management of press contacts—reveals how deeply this performance ethic has permeated even the private lives of those touched by the case.

The book critiques how narrative control often matters more than truth itself, and how public appetite for drama can eclipse any sincere reckoning with loss, guilt, or injustice. It asks the reader to question what stories survive, who gets to tell them, and how spectacle can warp the moral clarity of a murder trial into the sensational contours of entertainment.

Memory, Mythmaking, and the Politics of Legacy

The shaping of legacy is one of the most insidious and enduring struggles portrayed in Story of a Murder. From the very beginning, Crippen’s account dominates the historical record—not because it is convincing, but because he survives, speaks, and commands institutional amplification.

His version is repeated by police memoirs, sensationalized by newspapers, and canonized by true crime enthusiasts. Meanwhile, Belle Elmore—his murdered wife—is subjected to a double death: first physically, and then symbolically, as her character is dismantled to fit misogynistic narratives.

Even in popular culture, she is remembered as a shrill burden rather than as a woman of ambition, talent, and resilience. This selective memory reflects broader cultural mechanisms that valorize male charisma while diminishing female resistance.

Ethel Le Neve, too, experiences the dislocation of her identity, having to abandon her name and live in self-imposed anonymity, shaped by the fear that her past will catch up with her children. The book positions itself as a deliberate act of myth-busting, piecing together neglected documents, oral histories, and contradictions to expose the politics of how stories are remembered—or forgotten.

Memory is not a passive act but an active construction, shaped by power, convenience, and public appetite. In revisiting the Crippen case, the author refuses to let the sensational or the simplistic dominate.

She reframes the narrative not to exonerate or condemn, but to restore complexity. Ultimately, the book serves as a reminder that history, if left unchallenged, will always serve those with the loudest voices and the most privileged positions, unless careful, ethical acts of remembrance intervene.