Strange Pictures by Uketsu Summary, Characters and Themes

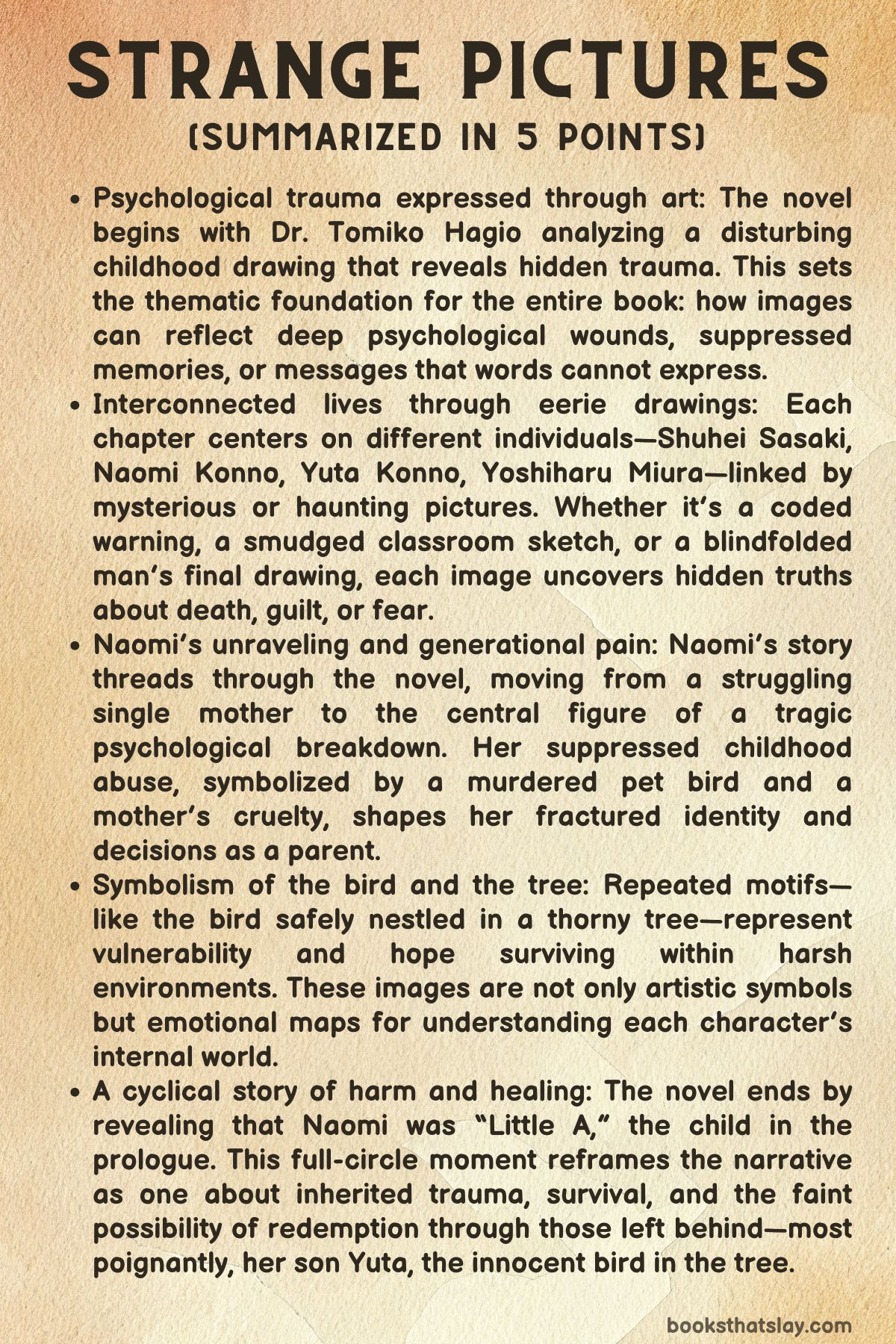

Strange Pictures by Uketsu is a psychological horror novel woven through fragmented narratives, all connected by unsettling illustrations and the emotional residue they leave behind.

It explores how trauma, memory, and silent suffering manifest through art—often as eerie, coded messages left behind by the broken. Told through a psychiatrist’s framing perspective, the book shifts between multiple protagonists grappling with grief, unresolved violence, and mental decline. With each chapter, drawings become more than images; they become testimonies, confessions, and warnings. Uketsu’s haunting storytelling blends supernatural undertones with real-world psychological insight, creating a deeply disturbing but human portrait of inherited pain.

Summary

Strange Pictures opens with a prologue narrated by Dr. Tomiko Hagio, a retired psychologist now working as a university professor. She introduces a disturbing drawing from a long-ago case involving a child known only as “Little A.”

The picture shows a house without a door, a child with a smudged-out mouth, and thorny branches surrounding a hollow in which a small bird hides. The drawing reflects abuse, voicelessness, and entrapment, yet the hidden bird offers a glimpse of hope and care amid trauma.

This analysis frames the entire novel thematically, positioning art as a conduit for psychological revelation.

In Chapter One: The Old Woman’s Prayer, we meet Shuhei Sasaki, a college student and member of the Paranormal Club. He and his friend Kurihara come across a strange blog called Oh No, Not Raku!. Initially lighthearted, the blog documents the joyful life of Raku and his wife Yuki as they prepare for their child’s birth.

But after Yuki’s sudden death during childbirth, the blog turns dark and cryptic, especially a final post years later where Raku writes about uncovering the secret of three specific drawings. Upon further investigation, Sasaki and Kurihara discover that these illustrations, when overlaid using subtle visual clues, reveal a horrific image: Yuki, lifeless, as an old woman in white cuts into her during what appears to be a forced C-section.

The suggestion is that Yuki knew she might be murdered or mistreated medically, and left the drawings as warnings.

Yet, she also left behind drawings of Raku and their child together in a peaceful future, revealing her hope despite terror. The chapter balances horror with emotional depth, presenting drawings as desperate acts of communication.

Chapter Two: The Smudged Room shifts focus to Naomi Konno and her young son Yuta. Naomi is a widowed mother struggling to cope with the challenges of single parenting and an undercurrent of paranoia—she believes a car is following her and Yuta. Their home life feels strained, particularly when Yuta begins to act strangely.

At his nursery school, Yuta draws a Mother’s Day picture that alarms his teacher: it features their apartment building, but their specific room is covered by a harsh, dark smudge. Naomi, already emotionally frayed, is haunted by the implication that Yuta may be internalizing something ominous.

The imagery, again, conveys unspeakable tension through childlike artistry, tapping into the theme of unspoken but visible trauma.

In Chapter Three: The Art Teacher’s Final Drawing, the story centers on Yoshiharu Miura, a gentle high school art teacher who is murdered during a solo mountain hike. At the crime scene, a strange, folded drawing is found—his last. Iwata, a former student turned journalist, investigates.

He learns that Miura created the drawing blindfolded, using a grid system he once taught to visually impaired students. The picture appears to be a dying message, cryptically revealing his murderer’s identity.

However, there are signs the crime scene may have been manipulated. This chapter blurs lines between confession, evidence, and misdirection, continuing the motif of pictures as vehicles for revelation, yet never offering absolute clarity.

The Final Chapter: The Bird, Safe in the Tree returns to Naomi, now imprisoned. Through flashbacks, we discover she was “Little A” from the prologue. Her abusive upbringing culminated in the traumatic killing of her pet bird Cheepy by her mother, an act that emotionally shattered her.

Naomi eventually retaliated violently and was institutionalized as a child. Despite everything, she tried to build a normal life, marry, and raise a son. But the echoes of childhood trauma were too strong. The story ends with journalist Isamu Kumai recovering in a hospital after covering Naomi’s case.

A mysterious visitor hints at the need to protect Yuta, Naomi’s son—the symbolic bird in the hollow tree, fragile but alive.

Through layered storytelling and emotionally resonant imagery, Strange Pictures blurs horror, mystery, and psychology, reminding readers that every drawing—no matter how simple or strange—tells a story, sometimes more truthfully than words ever could.

Characters

Dr. Tomiko Hagio

Dr. Hagio, a former psychologist turned professor, serves as the psychological lens through which we view much of the unfolding narrative. In the prologue, she introduces a drawing that encapsulates the trauma of a child named “Little A.”

Her role in analyzing the psychological significance of the drawing underscores her deep understanding of the human mind. Dr. Hagio’s past as a practitioner shows her empathy and insight, yet her professional detachment at times contrasts sharply with the emotional turmoil of the patients she studies, especially as we learn more about her relationship with the subjects of her psychological studies.

As the book progresses, Dr. Hagio’s reflections and the psychological themes she introduces play a pivotal role in unraveling the mystery.

Shuhei Sasaki

Shuhei Sasaki, a college student involved in a Paranormal Club, is a crucial character who embarks on a journey of discovery, initially driven by curiosity and later by a deeper sense of moral responsibility. Sasaki’s investigation into the strange blog and its cryptic messages reveals a man searching for meaning, not just for the truth about Yuki’s death but also for his place within the mystery itself.

His role evolves from a passive observer to an active participant, challenging his own understanding of the boundaries between the living and the dead. Through Sasaki’s arc, the narrative delves into themes of grief, loss, and the need for closure.

Yuta Konno

Yuta, the young boy at the center of Chapter Two, is a character shaped by his fractured family life. His mother Naomi struggles to raise him after the death of her husband, and his increasingly strange behavior reflects the psychological pressures and tensions within their home.

Yuta’s drawings, particularly the mysterious smudge on his depiction of the family’s apartment, become a symbol of the emotional turmoil and unseen forces affecting him. His silence and his detachment represent the often hidden impact of trauma, particularly how children internalize fears and unspoken tensions.

Yuta is not only a victim of his circumstances but also a symbol of innocence and fragility in a world that seems to offer little protection.

Naomi Konno

Naomi, Yuta’s mother, is one of the most complex and tragic characters in the book. Her past is marred by the suicide of her father and the subsequent emotional abuse at the hands of her mother. This trauma profoundly shapes Naomi’s adult life, especially in how she perceives love and safety.

The loss of her childhood innocence, especially after witnessing the brutal death of her pet bird Cheepy, is a defining moment. Naomi’s inability to reconcile her love for her mother with the emotional cruelty she endured leads to her eventual psychological unraveling.

Naomi’s actions in the final chapter, where she is arrested for crimes related to her past, offer a grim view of how unaddressed trauma can spill over into violence and destruction.

Yoshiharu Miura

Yoshiharu Miura, the high school art teacher, is a figure marked by deep personal dedication to his students and his craft. His death, under violent circumstances, sets off a chain of events that propels the narrative forward.

Miura’s final drawing, which he created blindfolded or in the dark, represents his attempt to communicate something vital before his death. His character symbolizes the power of art not only as a means of expression but as a tool for confronting uncomfortable truths.

Miura’s role as a teacher and mentor underscores the theme of unspoken bonds and the tension between appearance and reality. His tragic end and the mystery surrounding his death point to the broader theme of how even the most seemingly innocuous people may harbor darker secrets.

Raku and Yuki

The characters of Raku and Yuki, introduced through the blog entries, represent a domestic ideal that gradually turns nightmarish. Raku’s love for his wife Yuki and their shared joy in parenthood is shattered by the tragedy of her death during childbirth.

Raku’s later posts, revealing the strange and chilling messages in Yuki’s drawings, form a central piece of the mystery. Raku’s character is defined by his profound grief and the cryptic message he is left with. Meanwhile, Yuki’s drawings, which contain hidden symbols, hint at her foreknowledge of her fate, suggesting a deeper psychological and possibly supernatural connection to the narrative’s central mystery.

Themes

The Power of Images as Emotional and Psychological Mirrors

In Strange Pictures, the motif of drawings and images emerges as a significant theme that reflects the emotional and psychological states of the characters, shaping the narrative in complex ways. Throughout the book, images are not just representations of reality but tools for expressing deep, often hidden, emotions and thoughts.

Dr. Tomiko Hagio’s analysis of Little A’s drawing in the prologue demonstrates how an innocent piece of art can serve as a lens into trauma and psychological distress. The smudged mouth and the thorny tree branches in the drawing speak to Little A’s repressed fears, while the presence of the bird represents a longing for safety and protection, hinting at the character’s potential for healing.

This connection between drawing and trauma is reinforced as other characters use visual art to process their experiences. Each drawing gradually reveals more about their inner lives, reflecting the complex emotional layers of the characters.

The theme deepens in later chapters, such as in Chapter Two, where Yuta’s disturbing drawing of the smudged room reflects not only his own inner turmoil but also Naomi’s mounting fears of an unseen threat. This blend of external fear and internal anxiety shows how drawings can serve as a vehicle for expressing complex emotional states.

Similarly, in Chapter Three, Miura’s final drawing, left at the crime scene, becomes a crucial clue that hints at his murderer and his emotional state in the final moments of his life. It underscores the notion that art transcends the physical act of creation, holding the power to communicate urgent truths, even in death.

Thus, the theme of images as emotional and psychological mirrors is central to the book, symbolizing how visual representations can act as reflections of the characters’ deepest fears, traumas, and desires.

The Intergenerational Cycle of Trauma and Abuse

Another central theme in Strange Pictures is the exploration of trauma as a cyclical force that perpetuates itself across generations. This theme is embodied most poignantly in the character of Naomi Konno, whose life is shaped by a legacy of abuse that traces back to her mother’s own trauma.

The novel gradually unveils how Naomi’s childhood, marked by the suicide of her father and subsequent emotional neglect and abuse by her mother, forms the psychological foundation for her later actions.

Naomi’s relationship with her mother, particularly her mother’s cruel treatment of her pet finch Cheepy, is a defining moment in her life, one that marks the breaking point where Naomi’s own trauma transforms into a destructive force.

The concept of generational trauma is further illustrated in the relationship between Naomi and her son, Yuta. Naomi’s past is so intertwined with her present actions that it impacts her ability to parent Yuta, creating a cycle of emotional neglect and violence.

In the final chapter, as Naomi’s story is revealed, readers come to understand that she, like Little A, is a product of a broken and abusive system. The theme culminates in the chilling realization that Naomi’s own trauma mirrored that of the other characters, all of whom have been shaped by experiences of violence, loss, and neglect.

The novel suggests that trauma is not easily broken, often passing from one generation to the next, carrying with it the weight of past pains that can shape future lives in haunting ways.

The Hidden Nature of Evil and Its Disguises

Strange Pictures explores the theme of hidden evil, where malevolent forces operate beneath the surface, often disguised as everyday life or seemingly benign occurrences. This theme is especially prominent in the mystery surrounding Yuki’s death in Chapter One.

The narrative weaves a sense of unease and suspicion as Shuhei Sasaki and Kurihara delve into the cryptic blog posts by Raku, whose life initially appears peaceful but soon reveals disturbing truths. The inconsistencies in the blog’s entries and the hidden messages within Yuki’s drawings point to a deeper, more sinister reality that was concealed from the outside world.

This sense of concealed malevolence is reinforced by the unsettling feeling that the forces at play are both visible and invisible—much like the mysterious compact car stalking Naomi and Yuta in Chapter Two. The theme is further explored through the cryptic and violent nature of Miura’s death in Chapter Three, where his final drawing is not just an artistic creation, but a deliberate clue left behind.

The discovery of this drawing, interpreted as a dying message, reveals the theme of hidden evil in the form of betrayal and manipulation. The very act of leaving behind a cryptic image speaks to the darker, hidden motives at play.

The hidden nature of evil is thus depicted as something that can lurk beneath the surface of normality, manipulating the course of events and shaping the fates of those involved in subtle yet powerful ways.

The Psychological Impact of Isolation and Loneliness

A significant undercurrent in Strange Pictures is the exploration of isolation and loneliness, particularly how these feelings shape the psychological states of the characters and propel the narrative forward. Naomi Konno’s sense of isolation is emphasized in Chapter Two, where her growing paranoia and fear of being followed reflect her deep loneliness and sense of vulnerability.

Her single motherhood and the absence of support after her husband’s death contribute to her growing isolation, which is further exacerbated by the haunting feeling that something is stalking her. This sense of being alone in the world, without protection or comfort, mirrors the isolation experienced by other characters, like Little A and Miura.

The theme of isolation is also present in Miura’s tragic death in Chapter Three, where his solitary hiking trip culminates in his brutal murder. His isolation in the mountains, coupled with the violence of his death, symbolizes the emotional and physical solitude that defines his life.

The cryptic drawing he leaves behind, created in isolation, serves as a testament to how the loneliness of the characters often pushes them to find meaning or expression in the most desperate of circumstances. Ultimately, Strange Pictures portrays loneliness not just as a state of being but as a psychological prison that can distort perceptions of reality, leading characters down dark and dangerous paths.

The Duality of Human Nature and the Struggle Between Aggression and Protection

Another complex theme in Strange Pictures is the duality of human nature, particularly the tension between aggression and protection. This theme is most explicitly represented by the bird in the prologue’s drawing, which symbolizes both a potential source of safety and the violent potential for aggression.

The bird’s nesting in the thorny tree hints at the coexistence of two opposing forces within the same space—protection and harm. This duality is explored through characters like Naomi, who, despite her trauma and aggressive tendencies, shows moments of deep care for her son Yuta, symbolizing her desire to protect him from the same cycle of violence that consumed her own life.

This duality is mirrored in the other characters as well, such as Miura, who, despite his calm and selfless nature, becomes embroiled in a violent conflict that ultimately leads to his death. The theme suggests that every individual is shaped by both their capacity for kindness and the potential for destructive behavior.

The struggle between these two forces, often arising from trauma or unhealed wounds, becomes central to the characters’ journeys.

The novel portrays this internal conflict as an ongoing battle, with characters constantly trying to reconcile their desire for safety and love with the forces of violence and harm that they are incapable of fully escaping.