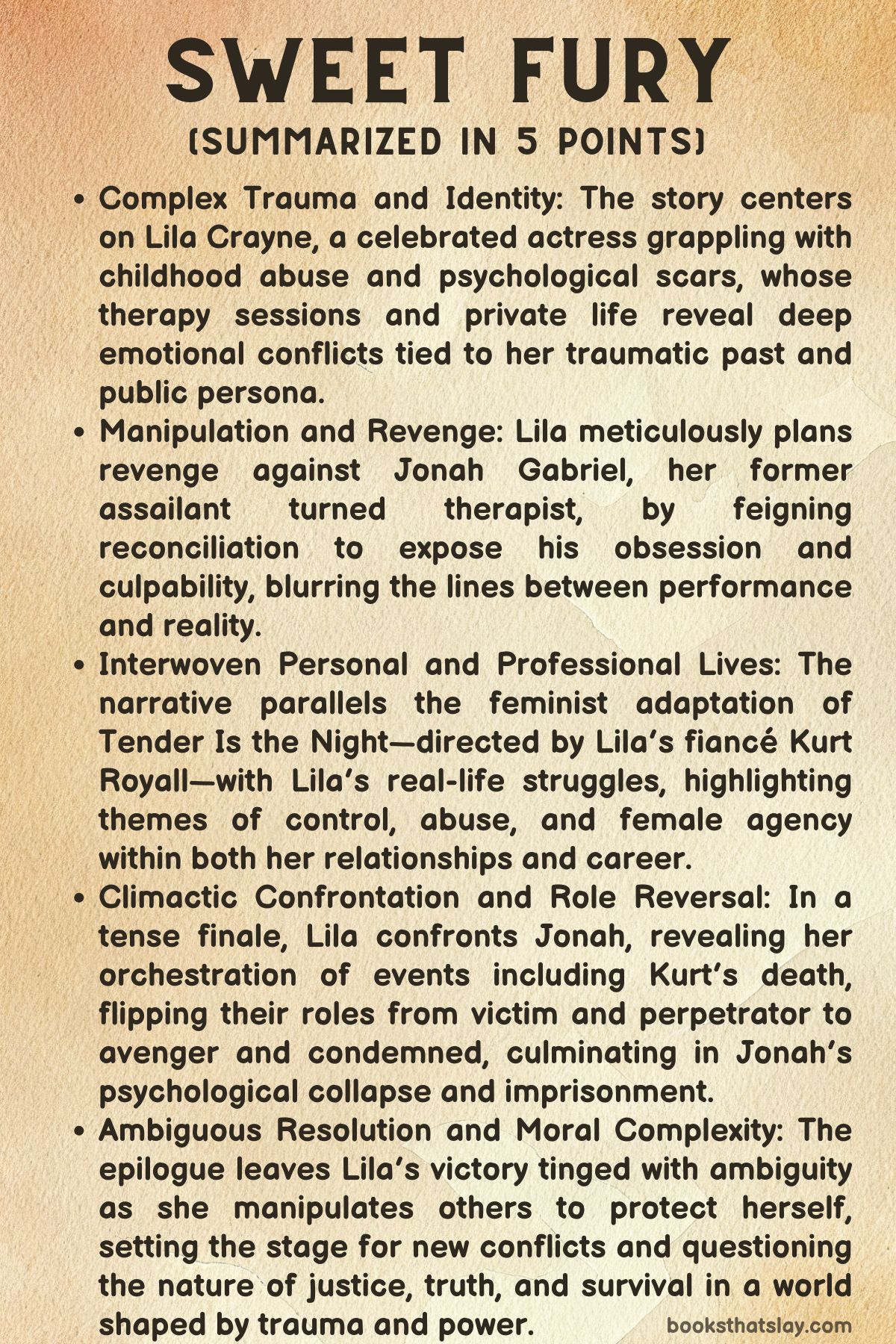

Sweet Fury Summary, Characters and Themes

Sweet Fury by Sash Bischoff is a layered psychological thriller and character study that follows Lila Crayne, a famous actress grappling with trauma, control, and revenge in the glossy but dangerous world of Hollywood. At the center of the story is the intense and ethically complex relationship between Lila and her therapist, Jonah Gabriel, which becomes the catalyst for a high-stakes game of deception, emotional manipulation, and hidden truths.

The novel examines how trauma is shaped by memory, power, and gender dynamics, offering a dark and intelligent exploration of the cost of survival in both personal and professional spheres.

Summary

The story begins with a disturbing image: Lila Crayne, a well-known actress, soaked in blood, making an emergency call. This moment foreshadows a violent climax that lingers in the background as the story progresses.

The narrative unfolds largely through therapy sessions between Lila and Dr. Jonah Gabriel, which Lila initiates under the pretense of preparing for a role in a feminist film adaptation of Tender Is the Night, directed by her fiancé Kurt Royall.

However, it quickly becomes evident that her psychological wounds run much deeper than professional stress.

Lila’s reflections on her role as Nicole Diver in the film evolve into personal revelations. She discusses her childhood—dominated by a violent, alcoholic father and a passive, traumatized mother—and her unresolved trauma surrounding his death in a drunk-driving accident, during which she and her mother were also present.

These memories, including a blackout from that night, become central to her therapeutic journey. Her history includes sexual assault in young adulthood, an experience she buried until now.

Lila’s past has shaped a pattern of silence, compliance, and guilt that continues into her present, especially in her relationship with Kurt.

Publicly, Lila and Kurt are Hollywood’s power couple. She throws a grand party to propose to him, appearing glamorous and confident.

Yet, their dynamic is riddled with unease. Kurt, who outwardly embraces feminist ideals, is controlling and emotionally abusive.

His manipulation becomes more apparent as filming for Tender progresses, particularly in how he treats Celia Scott, a young actress cast in the film who closely resembles Lila. Celia becomes a mirror of Lila’s past self—vulnerable, naive, and susceptible to Kurt’s charm and authority.

Karen Wolfe, Lila’s mother and manager, reaches out to Jonah with concerns about Kurt’s behavior, planting doubts about the true nature of Lila’s relationship. Meanwhile, Lila begins to project her emotions onto Jonah, developing an attachment that blurs therapeutic boundaries.

Jonah, though aware of these issues, begins to harbor feelings for Lila, compromising his professionalism.

As therapy sessions continue, Lila begins to uncover suppressed memories through EMDR, revealing that her mother may have deliberately caused the car crash to kill her abusive father. This reshapes Lila’s understanding of violence and agency, paralleling her current situation with Kurt.

Lila’s emotional repression and learned helplessness are slowly giving way to a recognition of power and survival.

Professionally, the film’s production becomes a stage for Kurt’s ego and cruelty. Lila, though still trapped, starts to take back some control—guiding Celia, protecting the script’s integrity, and subtly resisting Kurt’s domination.

In a Vogue interview, she perpetuates a false romantic narrative about her and Kurt’s early relationship, hiding the fact that he coerced her into sex before her contract was signed. Her narrative manipulation reveals both survival instincts and the price of truth in a hostile industry.

As Jonah becomes further entangled, his fiancée Maggie begins to suspect emotional infidelity. She confronts Jonah, who admits to inappropriate feelings for a patient.

Maggie demands a choice—her or Lila. Before he can act, Lila shows up at his home, visibly injured, insisting she can’t leave Kurt until the film is finished.

They hatch a secret plan to help her escape, though Jonah is clearly slipping into personal and ethical chaos.

At Maggie’s art gallery debut, Lila unexpectedly arrives and publicly supports her, further complicating Jonah’s emotional allegiances. This encounter brings both women into Jonah’s orbit, pushing him into deeper conflict.

Eventually, Lila confesses to Jonah that she was the ghostwriter behind the feminist script Kurt is producing, having used a male pseudonym to get it accepted. When Kurt discovered the truth, he vanished in rage.

To salvage the production, Lila begs her mother to negotiate his return, offering a morally troubling exchange that tightens the web of manipulation.

As Lila and Jonah continue to meet secretly, their bond grows dangerously close. Lila eventually professes her love, prompting Jonah to make a decision that could destroy both their lives.

Simultaneously, the narrative shifts to a flashback of their first meeting years earlier, at a masked ball during their college years. There, Jonah—unbeknownst to Lila—raped her under the pretense of protection and intimacy.

Lila never reported it but is haunted by the memory. Years later, a Yale student named Celia contacts her with a nearly identical story, confirming that Jonah repeated this pattern.

With this knowledge, Lila sets an elaborate trap. She pretends to be trapped in an abusive relationship with Kurt, baiting Jonah into saving her.

Kurt plays along, complicit in the plan. Lila feeds Jonah staged therapy notes and fabricated vulnerability, drawing him deeper into a false narrative.

When Jonah finally breaks into her apartment and stabs Kurt, believing he’s rescuing Lila, she reveals the truth: everything was orchestrated. Kurt collapses, and Jonah is left reeling.

Before he can fully comprehend the betrayal, Celia arrives, demanding justice for her own trauma.

But Celia soon realizes she, too, has been used. Lila never intended to support her voice—only her own revenge.

When Celia attempts to call the police, Jonah assaults her, nearly killing her until Lila intervenes with a knife, finally stopping Jonah’s rampage.

In the end, Jonah is imprisoned for life. Lila, ever the actress, prepares to reshape the narrative again.

She considers blaming Celia if needed, willing to do whatever it takes to preserve her image and freedom. Though justice is technically served, the novel closes with the haunting recognition that Lila’s manipulations continue.

Her trauma forged not only a survivor, but a woman who now thrives in the darkness she once tried to escape, ready to reemerge in another form, another story, another performance.

Characters

Lila Crayne

Lila Crayne stands at the emotional and narrative center of Sweet Fury, a woman whose surface brilliance as a celebrated actress masks a storm of trauma, manipulation, and self-deception. Her evolution from a haunted survivor to a calculating orchestrator of vengeance underscores the psychological complexity at the heart of the novel.

Lila is introduced as someone deeply fragmented—presenting poise and glamour in public while privately collapsing under the weight of past abuse and a present built on performative control. Therapy becomes both a lifeline and a theater for her as she revisits her history of familial violence, sexual assault, and exploitative relationships.

These sessions initially appear to offer a route to healing, particularly through her candid discussions with Jonah Gabriel, but they are later revealed to be carefully constructed performances, crafted to feed Jonah’s delusions and ultimately entrap him.

Lila’s relationship with Kurt Royall reveals a nuanced dance between dependency and domination. She appears subjugated—ashamed, anxious, and desperate to escape—yet it is eventually disclosed that she is not merely a victim but also a manipulator.

Her ability to rewrite narratives, as seen in the way she frames her sexual coercion by Kurt in a Vogue interview or ghostwrites an entire screenplay under a male alias, speaks to her survivalist instinct to adapt, conceal, and perform. Her connection with Jonah is laced with layers of past trauma—he was her rapist at Princeton, a masked predator she never confronted.

Yet she later ensnares him in a moral and emotional trap, baiting him into committing murder under the illusion of love and rescue. Lila’s final moments, where she contemplates preserving her story by manipulating public perception and deflecting blame onto others, crystallize her as a character who, while forged by trauma, reclaims power through cunning, performance, and ruthlessness.

She emerges not as a simple avenger or broken woman but as a deeply unsettling figure who embodies both victimhood and villainy.

Jonah Gabriel

Jonah Gabriel, the therapist at the heart of Sweet Fury, is a study in contradiction, emotional repression, and moral collapse. Initially presented as a concerned mental health professional attempting to help Lila through her trauma, Jonah’s persona gradually fractures to reveal a man shaped by delusion, self-justification, and unacknowledged guilt.

His therapeutic role is quickly compromised as he begins developing feelings for Lila, feelings rooted less in empathy than in a disturbing need to play the savior. Jonah’s sessions with Lila, far from offering professional distance, become a space where he projects his fantasies and guilt, culminating in ethical breaches that teeter on the brink of romantic obsession.

Beneath this professional mask lies a darker truth: Jonah was Lila’s rapist years earlier at Princeton, a crime he committed under the guise of anonymity during a secret society event. His manipulation then was masked by charisma and gaslighting, but in the present, he remains willfully ignorant of the truth, deluding himself into believing in their mutual connection.

As Lila re-enters his life under the guise of a patient in distress, Jonah’s internal boundaries collapse completely. He betrays his fiancée Maggie, disregards his ethical obligations, and eventually commits murder under the belief that he is saving Lila from Kurt’s abuse.

Jonah’s descent into violence and madness is punctuated by his inability to confront his past crimes and his desperate attempt to control the narrative of his own heroism. Even as evidence mounts of Lila’s manipulation, Jonah clings to the illusion of being needed, loved, and morally justified.

His ultimate breakdown—attacking Celia and nearly killing her—exposes the full extent of his deterioration. By the end, Jonah is not just a disgraced therapist or a failed lover; he is a dangerous predator whose crimes are finally exposed, not by remorse, but by the same women he sought to dominate.

Kurt Royall

Kurt Royall operates in Sweet Fury as both a symbolic and literal representation of toxic masculinity cloaked in progressive rhetoric. As Lila’s fiancé and the celebrated director of their joint project, Tender, Kurt embodies control disguised as artistry and feminism.

At the surface level, he is polished, charismatic, and visionary, often speaking publicly about empowering women and creating meaningful art. Privately, however, he is coercive, emotionally abusive, and manipulative, using his power not only to dominate Lila but also to exploit vulnerable young actresses like Celia.

His relationship with Lila is steeped in coercion from its inception—he forces her into sex before her contract is finalized—and that initial violation haunts their bond, despite the glamorous image they project to the world.

Kurt’s psychological hold over Lila is maintained through a blend of possessiveness and public adoration, creating a dynamic where Lila feels simultaneously trapped and flattered. Yet Kurt is not merely a brute; he is intelligent, calculating, and aware of how to craft a narrative that shields him from scrutiny.

His return to the film project after an initial disappearance—brokered by Karen Wolfe’s intervention—cements his position as a master manipulator, willing to bargain, vanish, or return when it suits his power.

In the end, however, Kurt becomes a pawn in a much larger and more sinister game orchestrated by Lila. Believing himself in control, he underestimates her capacity for vengeance and is ultimately murdered by Jonah, a death staged to look like a misguided act of rescue.

Kurt’s death, though brutal, is also symbolic—the final act in a web of manipulation where he, too, is outmaneuvered by the very woman he sought to dominate. His character illustrates how patriarchal power can implode when faced with equally ruthless resistance.

Maggie

Maggie serves as a foil to Lila in Sweet Fury, embodying emotional clarity, artistic passion, and moral outrage in contrast to the psychological entanglement that consumes Jonah and Lila. As Jonah’s fiancée, Maggie is perceptive and emotionally intelligent, attuned to the subtle shifts in their relationship that signal Jonah’s emotional infidelity.

Her confrontation with Jonah, where she demands honesty and clarity about his feelings for Lila, reflects her unwillingness to remain complicit in a toxic dynamic. Unlike Lila, who buries her truth under layers of performance and trauma, Maggie insists on authenticity and refuses to accept half-truths.

Maggie’s role expands beyond the domestic sphere when she debuts her own artwork at a gallery showing—a deeply personal act that suggests her own journey of self-expression and resilience. Her artistic success and integrity contrast with the manipulative artifice of Jonah and Lila’s relationship.

When Lila attends the event and publicly supports Maggie, it creates a collision of narratives: Maggie’s raw vulnerability and Lila’s carefully curated facade. This moment destabilizes Jonah further, forcing him to confront the damage he has done to the one person who truly saw him.

In the end, Maggie is not a central figure in the climax, but her presence lingers as a representation of an alternative path—one grounded in honesty, respect, and emotional accountability. Her decision to leave Jonah underscores her strength and refusal to be collateral damage in a story defined by abuse and deception.

Celia Scott

Celia Scott enters Sweet Fury as a young, vulnerable actress cast in the role of Rosemary—a character who echoes Lila’s own younger self and becomes a mirror through which the story examines cycles of abuse and exploitation. At first, Celia appears to be a symbolic victim of the industry: young, eager, and naive.

She is quickly positioned in Kurt’s crosshairs as his next conquest, and Lila watches with increasing dread as history threatens to repeat itself. However, Celia is more than just a passive figure.

Her trajectory transforms dramatically when it is revealed that she was also raped by Jonah, in a chillingly similar manner to Lila, years earlier at Yale.

This shared trauma draws Celia and Lila together, seemingly uniting them in a quest for justice. Celia trusts Lila’s leadership, believing they are working toward the same goal—exposing and punishing Jonah.

However, Lila’s ultimate betrayal of that trust is devastating. By manipulating Celia’s story to lend credence to her own plan of vengeance and then discarding her when she becomes inconvenient, Lila reveals her moral ambiguity and ruthlessness.

Celia’s climactic return to confront Lila and Jonah demonstrates her courage and sense of justice. Her attempt to contact the police signifies a refusal to be silenced, even when she realizes that her supposed ally has used her.

Celia is brutally attacked by Jonah in a horrifying final confrontation, but her survival marks a glimmer of resilience and the possibility of truth prevailing. Unlike Lila, Celia refuses to become a manipulator; her strength lies in her refusal to perpetuate cycles of deception, even at great personal cost.

Karen Wolfe

Karen Wolfe, Lila’s mother and manager, is one of the most enigmatic and chilling characters in Sweet Fury. She operates on the periphery of the central drama, yet her influence looms large over Lila’s development and choices.

As a mother, Karen is a paradox—both protective and predatory. Her history of suffering under a violently abusive husband forms the backdrop of Lila’s childhood trauma.

In a moment of desperate protection, she allegedly crashes the family car to kill her husband, a revelation that haunts Lila and complicates her understanding of victimhood and agency.

As a manager, Karen is shrewd, connected, and willing to broker morally compromising deals to preserve her daughter’s image and career. Her involvement in bringing Kurt back into the Tender project, through undisclosed but deeply troubling means, reveals her willingness to sacrifice others’ well-being—including Lila’s—for professional gain.

Despite her occasional moments of genuine concern, Karen ultimately embodies the entrapment of women in systems of power where violence and silence go hand in hand.

Karen teaches Lila how to survive through performance, manipulation, and narrative control, tools that Lila later weaponizes to orchestrate her revenge. Their relationship is marked by buried secrets, resentments, and a twisted form of loyalty.

Karen’s presence in the story functions not just as a mother figure but as a dark legacy—passing down a script of survival that blends maternal instinct with moral compromise. In the end, Karen is not redeemed, nor fully condemned.

She remains a spectral force in Lila’s psyche, a reminder of how trauma, power, and love can become dangerously entangled.

Themes

Trauma and Memory Manipulation

In Sweet Fury, the theme of trauma operates not just as emotional damage but as a field of narrative manipulation, power play, and self-definition. Lila Crayne’s life is defined by the remnants of violence, both experienced and inherited, yet the story resists a simple arc of victimhood.

Her traumatic past—including an abusive father, a manipulative mother, sexual violence, and professional exploitation—becomes a landscape she learns to rework and use to shape her own path. Her suppressed memories, unearthed through EMDR therapy, reveal not just past pain but long-concealed truths that offer her a semblance of control.

However, the novel blurs the ethical lines of recovery when trauma becomes something Lila consciously edits and even performs for her audience, whether that’s the public or her therapist. Her willingness to rewrite memories, adopt false narratives, and manipulate others through their own trauma questions the reliability of memory itself.

The book ultimately paints memory not as a static truth but as a dynamic tool—sometimes redemptive, sometimes sinister—especially when those memories are wielded by a woman trying to rewrite the script she has always been forced to follow.

Abuse Hidden Behind Glamour

The relationship between Lila and Kurt Royall explores how abuse can be camouflaged behind luxury, fame, and progressive ideals. On the surface, their relationship is aspirational—a Hollywood power couple at the center of a major feminist film adaptation.

But beneath that glossy exterior lies coercion, surveillance, and emotional domination. Kurt’s control doesn’t take the form of overt brutality at first; rather, it’s buried in his possessiveness, gaslighting, and public posturing as a feminist ally.

He uses professional dependence and public adoration to maintain his grip on Lila, who cannot separate her personal safety from her career obligations. Even moments of supposed intimacy, such as her public proposal, are laced with tension and performance.

Lila’s gradual realization that her abuse is not a failure of perception but a systemic manipulation by someone using feminism as a shield, marks a pivotal moment in her evolution. The theme lays bare how patriarchy often hides in plain sight, using the language of progress to continue cycles of control.

Power, Ethics, and Exploitation in Therapy

The relationship between Jonah Gabriel and Lila Crayne questions the integrity of therapeutic ethics and explores how power can be insidiously abused, even within spaces designed for healing. Jonah, a therapist entrusted with Lila’s psychological recovery, gradually crosses multiple boundaries—first emotionally, then physically, and eventually criminally.

The story scrutinizes how easily professionalism can collapse when clouded by unresolved guilt, attraction, and delusion. Jonah’s inability to separate his own emotional needs from Lila’s therapeutic process allows him to justify ethically abhorrent choices, ultimately culminating in murder.

Yet the narrative complicates the dynamic by revealing that Lila was never a passive subject. Her therapy entries, disclosures, and expressions of vulnerability were calculated, fictionalized performances crafted to manipulate Jonah into acting out her revenge.

What begins as a story of inappropriate transference becomes a power reversal, revealing that both the healer and the patient can exploit intimacy, trust, and vulnerability when their motives are corrupted. This theme questions the possibility of objective care in systems built on interpersonal dependency and emotional imbalance.

Feminist Reclamation and Performative Justice

The novel’s framing device—an adaptation of Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night—functions as a symbolic battleground for Lila’s broader attempt to reclaim narrative agency, not only in fiction but in her real life. Her reinterpretation of Nicole Diver’s story, emphasizing trauma, silencing, and reclamation, becomes both a metaphor and a strategy.

Lila ghostwrites the script and uses a male pseudonym to get it greenlit, reflecting how even female narratives require male sponsorship in patriarchal systems. Her performance of victimhood in therapy mirrors her on-screen role, both calculated to serve an end that the system would otherwise deny her.

However, the novel does not portray this reclamation as clean or heroic. Lila’s feminist justice is marred by her betrayal of Celia, whose shared trauma is used for strategic advantage rather than solidarity.

Lila’s feminism becomes not about communal healing but about personal sovereignty, emphasizing power over empathy. This theme reveals the tension between authentic justice and performative empowerment, asking whether survival in a patriarchal world demands moral compromise.

Revenge as Survival

Rather than positioning revenge as a reactionary or destructive force, Sweet Fury presents it as an elaborate, strategic means of survival. Lila’s decision to manipulate Jonah into killing Kurt is not born of sudden rage but careful planning, emotional seduction, and psychological staging.

It’s her only perceived way to escape a system that has consistently failed her—from the family that normalized abuse, to the institutions that ignored her rape, to the industry that required male mediation for her voice to be heard. Her revenge is not just against Jonah and Kurt but against the entire structure that empowered them.

Yet the narrative complicates the morality of her vengeance by exposing how others, like Celia, are collateral damage. Lila’s desire for sovereignty overshadows her ethical responsibility to the other women affected by Jonah.

Revenge, in this novel, is a complex assertion of agency that comes at a cost—it grants power, but it also isolates and hardens. The final impression is that Lila survives not through healing but through mastery of narrative, manipulation, and control, even if it leaves her morally untethered.