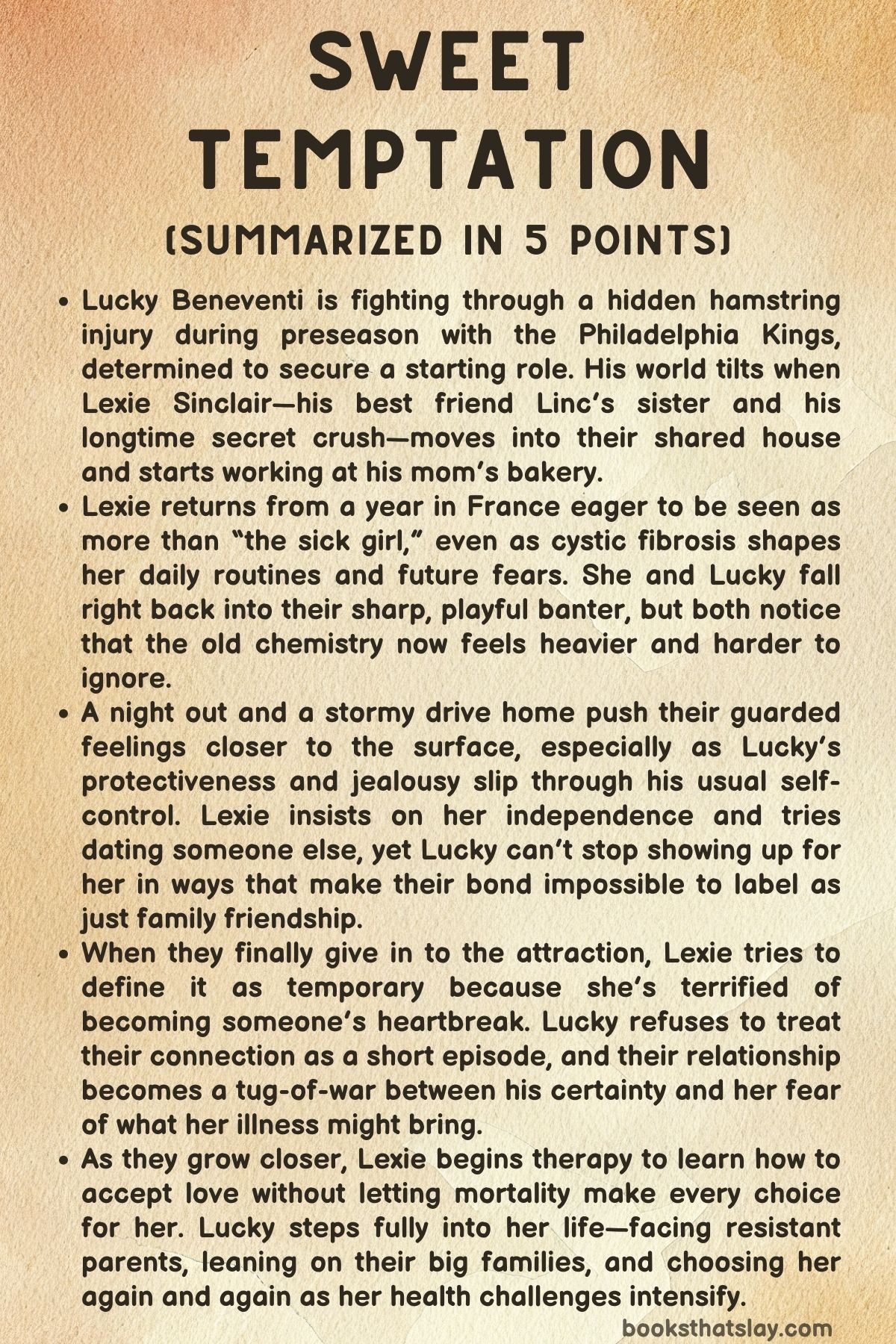

Sweet Temptation Summary, Characters and Themes

Sweet Temptation by Bella Matthews is a contemporary small-town sports romance that mixes slow-burn longing with the reality of living with chronic illness. Set in Kroydon Hills and orbiting an NFL team and a family bakery, the story follows Lucky Beneventi, a driven cornerback, and Lexie Sinclair, his best friend’s younger sister returning home after a year in France.

Their history is full of teasing, near-misses, and feelings neither has been brave enough to name. As adulthood reshapes their bond, they must decide whether love is worth the risk when time and health feel uncertain.

Summary

Lucky Beneventi finishes a punishing preseason practice with the Philadelphia Kings and quietly hides a hamstring injury because he’s close to earning a starting spot. In the locker room, his best friend and teammate Lincoln “Linc” Sinclair drops news that changes everything for Lucky: Linc’s sister Lexie is coming home from Paris and will be moving into the house Lucky shares with Linc and their other roommate, Lochlan.

Lucky has carried a secret crush on Lexie since they were kids, but he has always kept distance out of loyalty to Linc and fear of crossing a line. The thought of her living under the same roof rattles him, even as he pretends it doesn’t.

At dinner with the Beneventi family, Lucky’s brothers immediately sense how shaken he is. The family’s teasing turns into a warning that Lexie will be everywhere in his life again.

Lucky learns his mother has already hired Lexie to work at their bakery, Sweet Temptations, which means he can’t avoid her even if he tries. Lucky tells himself to keep control, but his nerves say otherwise.

Lexie arrives home after a full year studying and working in France. She feels proud of the independence she built abroad, where she wasn’t treated as fragile, and she wants that same freedom in Kroydon Hills.

Lexie lives with cystic fibrosis and manages her medication, enzymes, and breathing treatments daily. Although she’s happy to see family, she also dreads being coddled.

Her parents welcome her lovingly, and her mother reassures her that the move into Linc and Lucky’s house is still happening, honoring Lexie’s wish to live on her own terms.

When Lexie shows up with her luggage, she and Lucky fall into their familiar rhythm of sharp teasing. Underneath, everything has shifted.

Lexie notices Lucky watching her differently, and Lucky struggles to mask how grown-up she looks. Late that night, Lexie finds Lucky in the kitchen half dressed.

Their bickering softens as she cooks omelets, and Lucky listens while she admits how France let her feel normal and capable. His genuine respect catches her off guard, leaving her wondering what changed between them.

Friends and cousins help Lexie settle in, turning the move into a loud family gathering. Lexie’s confidence shows in the way she organizes her kitchen and grills dinner for everyone.

The next day she heads to Sweet Temptations, excited to start work, only to learn the bakery is closed for renovations. Her future mother-in-law-in-waiting insists Lexie rest and enjoy being young.

Lexie plans a pool and barbecue day with her friends instead.

Lucky comes home to find the backyard full of Lexie’s friends in bikinis, laughing and sunning. He’s stunned by Lexie’s beauty and his own reaction.

Acting on impulse, he brushes hair behind her ear, then immediately retreats, harshly telling her to cover up so she won’t burn. Lexie is hurt and confused; Lucky is furious at himself for slipping.

On the field, Lucky finally earns his roster spot, a moment of pride that proves he belongs by talent alone. Back at home, the tension with Lexie grows.

In the kitchen, Lucky sucks icing off her finger without thinking. The move shocks Lexie and makes her admit to her friends that something between them feels dangerously close to real.

She tries to convince herself it can’t happen.

Rainy weather brings another turning point. Lexie goes out with her cousins and friends to West End, Maddox’s bar, and finds Lucky already there.

She drinks more than usual and dances, newly determined to live boldly instead of cautiously. Lucky watches her like a man trying to hold onto restraint.

When another guy puts his hands on her hips, Lucky’s jealousy flares even though he pretends it doesn’t. He drives her home, scolding her about the storm and her health, and Lexie snaps that he isn’t her brother or her keeper.

In the kitchen afterward, she feeds him grilled cheese, and their argument turns quiet and intimate. Lucky finally admits he has never seen her as a sister.

Lexie goes upstairs shaken, her old crush roared back to life.

The next morning Lucky’s father warns him to stay away from Lexie, citing family ties and her health. Lucky explodes, tired of being told who he can love.

He decides he won’t let anyone dictate his choices anymore.

At a last-summer beach weekend, Lucky can’t hide his protectiveness or his irritation when Lexie announces a date with Brice, the man she met at West End. Lexie insists she’s allowed to date without Lucky’s approval.

The dinner turns into a disaster when Brice proves rude and opportunistic. Lucky steps in when Brice brings her home, sending him away and offering Lexie comfort.

The gesture sinks deep, even as Lexie tells herself she needs distance.

Lochlan, preparing for a SEAL deployment, notices Lucky’s feelings and pushes him to stop waiting. He also reminds Lucky to respect Lexie’s need for independence.

Later, when Lexie’s medication triggers a sudden migraine, Lucky takes control gently—getting her medicine, keeping her calm, and staying close until she feels steady. Their bond tilts from old friendship into something neither can deny.

Back in Kroydon Hills, Lexie admits to her cousin Dillan that her feelings for Lucky are growing, but fear cages her. She believes a serious relationship would end in heartbreak because her illness is progressive and life-shortening.

One stormy night, their restraint finally breaks. They confess desire, and Lexie allows herself one night with him, demanding no promises beyond that.

Lucky agrees, and they come together knowing it changes everything.

Morning brings panic for Lexie. She’s terrified of being seen, of what it means, and of how quickly she wants more.

Lucky, already sure, tells Linc the truth, hoping Linc’s easy acceptance will help Lexie stay. Instead, Lexie feels betrayed and stormed over.

She bakes to calm herself, then breaks down to her best friend Brea, admitting her real fear: she can’t bear the thought of someone loving her and watching her fade. Brea challenges her to stop deciding the future alone.

Lucky realizes he mishandled things and tries to apologize through small acts—learning to cook her favorite omelet, leaving notes, showing up with patience. Lexie stays angry until they finally talk in the rain.

She reminds him of a teenage night they once spent swimming in a storm, followed by her hospitalization and his sudden withdrawal. Lucky admits guilt and says both sets of parents pushed him away.

Lexie insists her illness was never his fault, but she also reveals her lungs will keep worsening. She refuses to let him become her caretaker or her mourner.

Lucky answers with stubborn devotion: he wants every day with her, however many they get. Their conversation ends in another night together, and although Lexie repeats her warnings, Lucky refuses to step back.

Lucky makes a grand gesture at the bakery—covering it in daisies, her favorite flowers, and a note promising to live loudly with her. Lexie is overwhelmed and moved.

She gives in to the truth she’s been resisting: she loves him, and she wants to try. She starts therapy to learn how to accept love without letting fear run her life.

As fall arrives, Lexie’s health wobbles with infections and antibiotics, but her relationship with Lucky steadies. Lucky learns her routines, meets her doctor, and stays attentive without smothering.

He also confronts Lexie’s father, Cooper, who still blames Lucky for the teenage scare. Lucky declares he will marry Lexie with or without approval.

Cooper can’t accept it yet, but Lexie’s mother supports Lucky’s sincerity.

Lexie throws herself into planning Lucky’s surprise birthday at West End, baking an enormous cake while pushing through exhaustion and worsening coughs. Lucky, meanwhile, works with his sister to choose an engagement ring.

At the party, Lexie’s joy shines, but Lucky sees how sick she is. He carries her to a private room and proposes, vowing to love her wildly for the rest of his life.

Lexie says yes, promising him her lifetime, even if it’s shorter than they want. Moments later her breathing crashes, and she collapses.

At the hospital, doctors say her lungs are failing and place her in a medically induced coma to fight infection. Lucky takes leave from football to stay at her side.

Cooper finally apologizes, admitting Lexie always felt safe with Lucky. After days of waiting, Lexie wakes, weak but still herself, and they talk about marrying as soon as she’s strong enough.

When she’s discharged, Lexie refuses to return to work right away. Instead she insists they fly to Las Vegas during the team’s trip and get married quietly, choosing joy over delay.

Two weeks later, family and friends gather back home to celebrate. Lucky toasts Lexie, promising to cherish every day they have.

Surrounded by love, laughter, and the bakery’s sweetness, Lexie and Lucky step into married life with open eyes and open hearts.

Characters

Lucky Beneventi

Lucky Beneventi is the emotional and narrative engine of Sweet Temptation – Bella Matthews. On the surface he’s the classic high-performing athlete: disciplined, fiercely competitive, and determined to earn his place as starting cornerback for the Philadelphia Kings without leaning on his family name.

That drive also defines how he holds pain and fear inside—playing through a hamstring injury, swallowing jealousy, and burying love for years because he thinks restraint is the same as loyalty. Underneath, Lucky is deeply tender and protective in a way that often comes out clumsy or intense.

His lifelong love for Lexie sits at the intersection of devotion and guilt; he’s terrified of hurting her, terrified of losing her, and even more terrified of being powerless against her illness. His arc is about unlearning control as a form of care.

He moves from keeping distance “for her good” to choosing presence even when it guarantees heartbreak. The grand gestures, the stubborn insistence on “we are happening,” and his willingness to step into conflict with both families show that his love is not a phase or a fantasy—it’s a decision he makes over and over, even when Lexie resists.

By the end, Lucky becomes the kind of partner who doesn’t just adore Lexie’s strength but also holds her fragility without flinching.

Lexie Sinclair

Lexie Sinclair is a heroine shaped by two equally powerful truths: she is vibrant and capable, and she lives with cystic fibrosis that steadily narrows her future. Her year in France reveals how much she craves an identity beyond “the sick girl,” and coming home forces her to renegotiate independence in a world that loves her fiercely but sometimes smothers her.

Lexie’s personality is steel wrapped in spark—quick-witted, stubborn, playful, and proud of being useful, especially through baking and caring for others. Yet her sharpness often functions as armor.

Her deepest conflict isn’t whether she loves Lucky; it’s whether she has the right to let herself be loved when she believes her ending is already written. Lexie carries a quiet, ongoing grief for her own life, and she tries to protect everyone by pre-mourning herself—setting boundaries like “one night only” to limit the damage she thinks she’ll cause.

Her development is slow and brave: she chooses therapy, accepts help, and gradually lets hope share space with realism. Lexie does not become “cured” by love; instead, she learns to live fully inside uncertainty, allowing joy without pretending tragedy can’t return.

Lincoln “Linc” Sinclair

Lincoln “Linc” Sinclair plays the role of bridge and gatekeeper between Lucky and Lexie. As Lucky’s best friend and Lexie’s brother, he embodies the family bonds that make their romance both risky and inevitable.

Linc’s outward vibe is confident and teasing, but it’s paired with sincere protectiveness and a deep belief that the people he loves should be happy, even if it surprises him. His humor and casual acceptance of Lucky and Lexie together show that he sees their connection as long overdue, not forbidden.

At the same time, Linc’s protective streak occasionally flares into territorial tension, especially around Lexie’s well-being or when other men show interest in her. He serves as emotional pressure relief in the story—lightening heavy moments—while also representing the supportive family voice that pushes the couple forward rather than policing them.

Lochlan Sinclair

Lochlan Sinclair is the quiet moral compass among the younger generation, with a steadiness sharpened by his SEAL career. He’s loyal, perceptive, and emotionally brave in a way that contrasts with Lucky’s tendency to hide.

Lochlan sees through Lucky’s history of restraint and calls it out without cruelty, urging him to stop wasting time and to treat Lexie’s independence as sacred rather than fragile. His presence expands Lexie’s world too; because he’s leaving for deployment, their conversations naturally drift toward mortality, fear, and what it means to love someone whose path is dangerous or uncertain.

Lochlan’s “just in case” letter to his parents parallels Lexie’s own acceptance of risk, making him a thematic mirror: both he and Lexie live with futures that might be cut short, but neither wants fear to be the dominant story.

Rome Beneventi

Rome Beneventi functions as both family ballast and comedic heat. As Lucky’s brother, he’s tuned into Lucky’s emotions early and isn’t afraid to pry, tease, and push him toward honesty.

Rome represents the Beneventi family culture of loud love—supportive, meddling, and relentlessly observant. He doesn’t carry the same burden of guilt about Lexie as Lucky does, so he’s freer to react like a spectator rooting for a pairing everyone saw coming.

Rome’s steady presence helps normalize the relationship within the Beneventi orbit, reinforcing that Lucky isn’t alone in choosing Lexie.

Ryker Beneventi

Ryker Beneventi is the blunt truth-teller Lucky needs when romance gets messy. He isn’t primarily a soft comforter; instead, he’s the guy who names the violation when Lucky oversteps, like outing Lexie’s private boundary to Linc.

Ryker believes in accountability as a form of love, forcing Lucky to face the difference between good intentions and good behavior. That role matters in Lucky’s growth, because Ryker anchors him to humility and respect rather than sheer determination.

Brea

Brea is Lexie’s ride-or-die confidante and emotional lifeline. She reads Lexie’s mood instantly, offers a safe space for breakdowns, and is willing to hate Lucky on Lexie’s behalf until she’s sure Lexie is safe.

But Brea is not just protective—she’s also wise about Lexie’s patterns. She recognizes that Lexie’s “one night only” rule isn’t about desire; it’s about fear of being mourned.

Brea gently challenges that self-protective logic, refusing to let Lexie shrink her life preemptively. Her friendship represents the kind of love that doesn’t tiptoe around illness; it looks directly at the darkness and still argues for joy.

Amelia Beneventi

Amelia Beneventi is warmth made human—maternal, intuitive, and gently strategic. As Lucky’s mother and the owner of Sweet Temptations, she integrates Lexie into the Beneventi family not as a fragile guest but as someone valued for her ambition and skill.

Amelia’s care shows up in practical affection: hiring Lexie, advising Lucky, bringing soup, teaching omelets, and making it clear that Lexie’s tears are a line no one crosses. She also embodies the adult viewpoint on loving someone sick: she warns Lucky that love will cost him pain, but she never argues that the pain makes love a mistake.

Her role is to bless, steady, and quietly guide both younger characters toward the kind of commitment they’re scared to claim.

Cooper Sinclair

Cooper Sinclair is Lexie’s father and the story’s primary barrier rooted in fear rather than malice. His hostility toward Lucky is fueled by a past incident where he believes Lucky’s choices contributed to Lexie’s hospitalization.

But underneath the anger is terror—the helpless dread of a parent watching a child deteriorate. Cooper tries to manage that terror through control and blame, clinging to the idea that if he can police Lexie’s risks, he can protect her.

His eventual apology is significant because it signals surrender to reality: he can’t rewrite Lexie’s illness, and he can’t deny the safety she feels with Lucky. Cooper’s arc is about loosening his grip on fear and making room for Lexie’s autonomy.

Carys Sinclair

Carys, Lexie’s adoptive mother, offers a softer but equally powerful counterbalance to Cooper. She sees Lexie clearly—not as breakable porcelain but as a young woman who deserves big love.

Carys supports Lexie’s independence, encourages therapy, and uses her own life as proof that loving fully despite risk is worth it. She is emotionally fluent, able to hold Lexie’s fear without amplifying it, and she becomes a quiet advocate for Lucky when Lexie’s doubts threaten to shut everything down.

Caitlin Beneventi

Caitlin Beneventi acts as Lucky’s tactical ally and emotional drill sergeant. She doesn’t coddle him; she pushes him to step up, think bigger, and commit with clarity.

Her involvement in planning gestures and the engagement ring reflects the Beneventi family’s belief that love should be bold and visible. Caitlin’s role is to keep Lucky from retreating into guilt or indecision by reframing love as action, not just feeling.

Dillan

Dillan, Lexie’s cousin, serves as her sounding board when romance and mortality start tangling into one knot. Lexie can admit fears to Dillan that she can’t fully say to Lucky yet—especially the terror of a shortened future and what that means for a partner.

Dillan’s presence reinforces a key theme: Lexie isn’t isolated in her illness; she is surrounded by people who love her enough to hear hard truths without fleeing.

Aurora

Aurora is part of Lexie’s friend circle and helps represent the normal, messy, youthful life Lexie wants to claim. Her online sleuthing of Brice and lively presence at girls’ nights show how Lexie’s world isn’t defined only by treatments and coughing fits.

Aurora embodies the peer pressure toward fun and recklessness that Lexie both enjoys and must navigate more carefully than others.

Saylor

Saylor is another piece of Lexie’s chosen family, functioning as social glue in group scenes. She contributes to the sense of community and shared history in Kroydon Hills, helping frame Lexie not as a patient returning home but as a friend returning to a life full of inside jokes, bikinis, book club chaos, and beach weekends.

Brice

Brice is less a romantic contender and more a narrative catalyst. His initial appearance gives Lexie a chance to assert her right to date and live like everyone else, pushing against Lucky’s possessiveness and her own lingering crush.

The date’s collapse—his rudeness, opportunism, and disrespect—sharpens Lexie’s understanding of what she actually wants: not a distraction, but depth. Brice’s role is to contrast Lucky’s steady care with shallow charm, clarifying the emotional stakes for both leads.

Dr. Fiore

Dr. Fiore functions as a doorway to Lexie’s internal transformation.

The doctor doesn’t “fix” Lexie; instead, she offers a framework where Lexie can explore love, fear, and mortality without pretending any of those feelings are wrong. Dr. Fiore’s presence signals Lexie’s shift from coping alone to letting herself be supported in a healthier way, turning therapy into a form of agency rather than surrender.

Elodie

Elodie represents another mirror of Lexie’s struggle with identity and legacy. Her determination not to ride her famous uncle’s label parallels Lucky’s desire to earn his spot without nepotism and Lexie’s wish to be seen beyond CF.

Elodie’s decision to restart her album and move to Kroydon Hills reinforces the theme of choosing authenticity over shortcuts. She also helps widen Lexie’s world beyond illness and romance, grounding her in friendships and future-planning even as her health worsens.

Coach Declan Sinclair

Coach Declan Sinclair is a smaller-screen character but symbolically important. By telling Lucky he’s earned his roster spot and won’t dress for the preseason finale, Declan validates Lucky’s core insecurity about family influence.

This moment strengthens Lucky’s self-worth, which matters because he needs that solidity to stand beside Lexie without feeling like he’s borrowing strength from anyone else.

Maddox

Maddox as the bar owner at West End provides the social stage where several turning points occur—Lexie’s night out, her surprise party for Lucky, and the public celebration of love and community. He’s part of the ecosystem that makes Kroydon Hills feel like a living, supportive village where emotions play out in front of people who care.

Jack Madden

Jack Madden, Elodie’s famous uncle from Six Day War, is a background presence that reinforces the story’s preoccupation with earned worth and the weight of legacy. His existence is not about direct action but about the temptation of easy routes—routes Elodie refuses, much like Lucky refuses shortcuts in football and Lexie refuses to be reduced to a medical narrative.

Themes

Love that refuses to be cautious

From the moment Lexie returns, desire is treated as something both exhilarating and dangerous, not because it is sinful, but because it threatens to rearrange the rules that have kept everyone feeling safe. Lucky’s attraction has never been casual; it is years of restraint, loyalty, and fear packed into one person.

The story keeps showing how love can be an act of defiance against systems built to prevent pain. Lucky has been trained by family and circumstance to be careful with Lexie—careful because she is Linc’s sister, careful because she is medically fragile, careful because a past mistake seemed to prove that wanting her could hurt her.

Yet what makes their relationship powerful is that it refuses to stay inside those guardrails. When Lucky finally admits he has never seen her like a sister, he is not just confessing desire; he is rejecting the false narrative that caring means staying distant.

Lexie, meanwhile, wants love badly but has learned to associate it with future grief. Her insistence on “one night only” is not a lack of feeling; it is her attempt to control the size of the wound she expects to leave behind.

The tension between them is built from two kinds of protectiveness—his urge to hold on, her urge to let go before the holding becomes unbearable. Over time, love becomes less about chemistry and more about choice: Lucky chooses to take her seriously, to learn her routines, to accept pain as part of devotion; Lexie chooses to stop treating love as a countdown to disaster.

The proposal, coming exactly when her body begins to fail, captures the theme in its rawest form: love here is not postponed until life is stable. It happens inside storms, hospital rooms, family conflict, and fear.

The relationship is framed as a decision to live fully rather than safely, and the novel argues that taking love while it’s available is not reckless—it is honest.

Illness, mortality, and the right to live anyway

Lexie’s cystic fibrosis is not a background trait; it shapes her sense of self, her decisions, and the emotional rhythm of the book. What stands out is how the narrative refuses to reduce her to suffering while also refusing to minimize the truth of her condition.

In France she enjoyed being seen as capable before being seen as sick, and that experience becomes a measuring stick for what she wants from home: autonomy, expectation, and dignity. The story shows the everyday labor of chronic illness—enzymes, nebulizers, migraines, antibiotics, appointments, breathless mornings—and uses those details to demonstrate that survival is work.

But Lexie’s deeper struggle is psychological: she believes she has already made peace with dying, yet she has not made peace with living while death is possible. Her fear is not just of pain or decline, but of being the reason someone else is destroyed.

That is why romance feels terrifying in a way friendship doesn’t. Friends and family, in her mind, will be buffered by time and community; a partner will face the loss directly, daily, intimately.

The theme develops through her therapy sessions, where she begins to challenge the idea that protecting people requires withholding herself from them. The novel also explores how illness rearranges power in love.

Lexie does not want to be managed, children-proofed, or treated like a fragile object, and Lucky has to learn the difference between care and control. His vigilance—checking her color, urging her to call her doctor—comes from love, but it risks echoing the suffocating caution she ran from.

Their growth happens when Lexie is allowed to be sick without losing her adulthood, and when Lucky accepts that his role is to stand beside her, not steer her. The ICU arc takes the theme to its limit: illness becomes a shared reality instead of a private burden.

Lucky’s choice to take leave and stay with her shows love moving from desire into commitment under pressure. Lexie waking up and joking through weakness is a quiet insistence that she is still herself, still alive, still worthy of joy.

The book ultimately treats mortality not as a reason to stop hoping, but as a reason to stop delaying.

Family loyalty, protection, and interference

The families in Sweet Temptation are loud, close, and deeply involved, and that closeness creates both safety and suffocation. Love is never only between two people here; it is continuously mediated by siblings, parents, cousins, and the long memory of shared history.

Linc’s protectiveness over Lexie shows a brother’s instinct to shield her from harm, but it also reflects the family’s habit of deciding what is best for her. Cooper’s hostility toward Lucky is not rooted in cruelty so much as terror—terror of seeing his daughter hurt, terror of past mistakes repeating, terror of having no power over a disease he cannot fight.

That fear turns into control, and control turns into conflict. Lucky’s father embodies another kind of interference: he tries to manage Lucky’s choices through warnings about ties and consequences, believing that preventing heartbreak is a parental duty.

The theme is not “family is bad”; it is that family love can become dangerous when it refuses to accept adulthood. Lexie’s move into Linc and Lucky’s house is a quiet rebellion against being treated as breakable.

She wants to live among noise and mess and desire, not in a padded room of good intentions. At the same time, the novel honors the beauty of this network: the way everyone shows up at the beach, the way meals are shared, the way teasing becomes a language of belonging.

The Beneventis and Sinclairs function like a protective wall around Lexie, and that wall holds during the hospital crisis. Yet the story insists that walls can also block air.

The turning point comes when family members start shifting from gatekeepers to supporters. Carys advocates for Lexie’s right to love; Lincoln, after initial teasing, becomes normalization rather than obstruction; even Cooper eventually apologizes, realizing that his fear has been misdirected.

Through these arcs, the book argues that real family loyalty is not the same as control. Loyalty means supporting the choices that make someone feel alive, even when those choices carry risk.

Interference is shown to be born from love, but the novel keeps stressing that love without trust can become another kind of harm.

Independence and the fight to be seen as whole

Lexie’s return from Paris is framed as more than coming home; it is coming back as someone who has practiced being fully herself in a place without her old labels. The biggest label she is fighting is “the sick girl.

” The theme of independence is shown in small decisions—driving herself, drinking even when it may not be wise, dating Brice simply because she can, insisting on living with her brother and Lucky, taking control of her therapy. None of these choices are perfect, and the novel doesn’t pretend they are.

Instead, it emphasizes the right to choose imperfectly as part of adulthood. Lexie’s independence is also emotional.

She refuses a relationship at first not because she is weak but because she has a grim form of agency: she is trying to manage the outcome she expects. Therapy becomes the space where she challenges that logic and starts letting herself want more than survival.

Lucky’s journey mirrors this theme from another angle. He is fiercely independent in his career, pushing through injury and fear to win a starting spot on merit, not family advantage.

His pride in earning his role echoes Lexie’s pride in her accomplishments abroad. Both characters are resisting being defined by other people’s expectations.

Their romance tests that independence. Lucky has to learn to love Lexie without turning love into supervision, and Lexie has to learn that accepting help is not the same as losing agency.

You see this when she has a migraine and lets Lucky care for her—not as a surrender, but as trust. You also see it when Lucky refuses condom-free sex despite desire; the refusal is not control over her body, but a boundary meant to protect a shared future.

Independence in this book is not solitary strength; it is the ability to remain yourself inside intimacy. By the end, Lexie is still sick, still stubborn, still afraid at times, but she is no longer shrinking her life to spare others.

She is choosing love, marriage, and celebration while keeping her voice intact. The theme lands on a quiet but radical message: being whole does not require being invulnerable.

Guilt, forgiveness, and rewriting the past

A key emotional engine of the story is the teenage memory of rain, rebellion, hospitalization, and disappearance. That night became a myth inside both Lucky and Lexie.

For Lucky, it is proof that wanting her leads to harm; for Lexie, it is proof that being wanted is temporary. The theme explores how guilt can fossilize people in old versions of themselves.

Lucky’s guilt isn’t abstract; it is bodily, tied to the image of Lexie struggling to breathe because he pulled her into something risky. Even if the illness caused it, he experienced the event as a personal failure.

That guilt shaped years of distance, womanizing, and self-denial. Lexie’s hurt from his withdrawal shaped her fear of depending on him.

Their adult relationship can’t begin honestly until they open that locked room together. When Lexie states plainly that her illness was never his fault, she is offering him a kind of absolution no one else could give.

Yet forgiveness is not instant, because guilt has been part of his identity. The story shows forgiveness as a process of accepting reality instead of clinging to punishment.

Lucky needs to believe he deserves love to accept Lexie’s love; Lexie needs to believe she won’t be abandoned to accept his commitment. Their conversations in the rain mark a mutual rewriting of meaning: the past is still painful, but it is no longer destiny.

Family guilt also appears in Cooper’s arc. He has carried blame toward Lucky for years, using it as a way to make sense of a frightening world.

His apology in the hospital is not only about Lucky; it is about letting go of a story that kept him angry because anger felt safer than helplessness. The novel suggests that guilt is a way people try to gain control over what cannot be controlled.

Forgiveness, then, is not sentimental; it is surrendering that illusion. It allows the characters to return to the present, where love is possible again.

By the time Lucky proposes and Lexie says yes, they are no longer acting out the past, but choosing a future that acknowledges risk without being ruled by old wounds.