Taiwan Travelogue Summary, Characters and Themes | Shuang-zi Yang

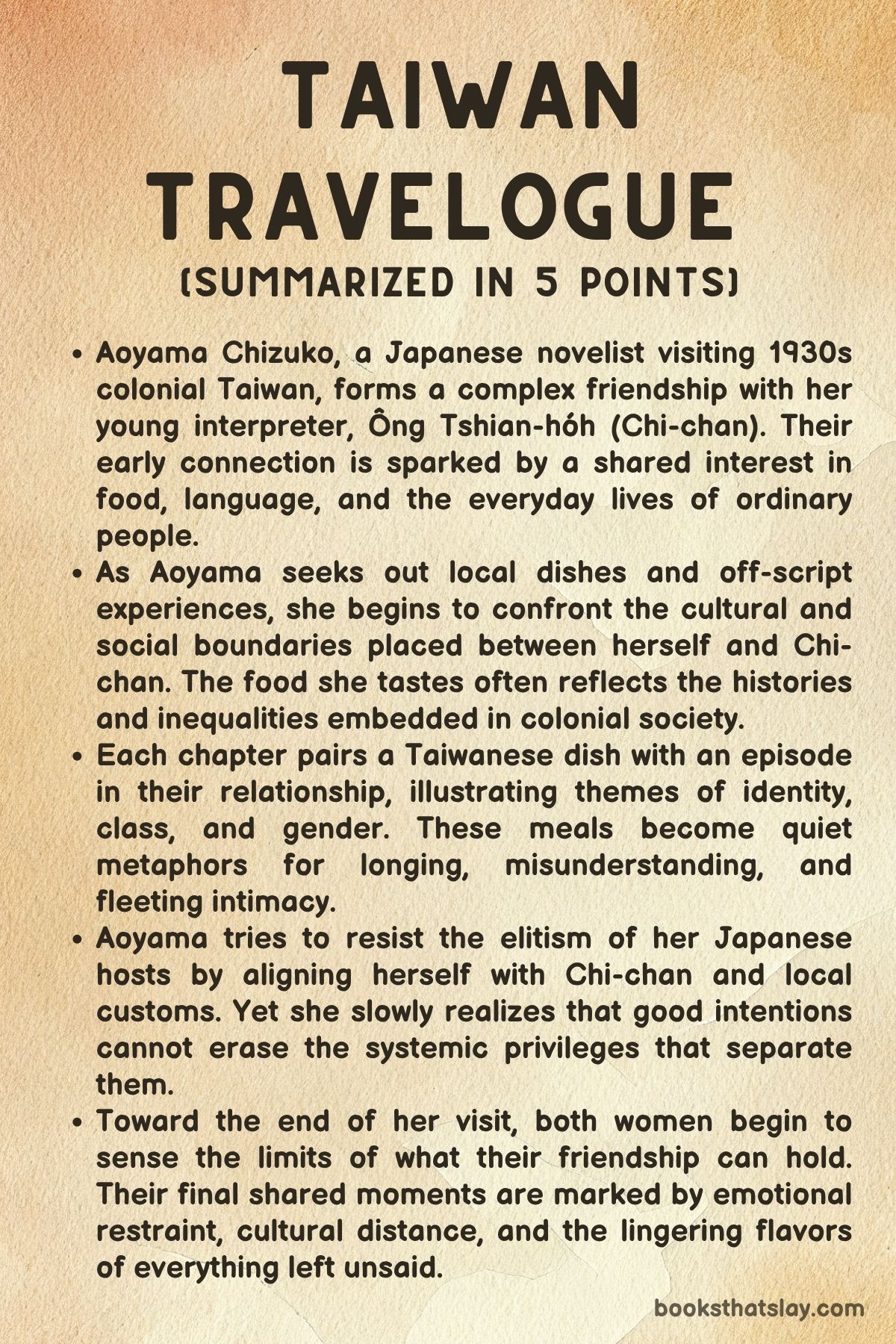

Taiwan Travelogue by Shuang-zi Yang is a poignant and intimate exploration of identity, colonial tension, female friendship, and the complexity of cultural exchange during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan in the 1930s. Told through the eyes of Aoyama Chizuko, a Japanese writer visiting Taiwan, the memoir captures more than just landscapes and cuisine—it delves into the emotional and ideological transformations that unfold between people separated by language, class, and empire.

Through her relationship with the local interpreter Chi-chan, Aoyama comes to question not only her place in the world but also the structures of power and affection that shape her interactions. This is a deeply reflective and evocative work that transcends the genre of travel writing.

Summary

Taiwan Travelogue begins with Aoyama Chizuko’s arrival in colonial Taiwan in 1938, a journey initially shaped by nostalgia and an almost theatrical sense of curiosity. Her first impressions of Taichū—modern-day Taichung—are vivid and sensory, steeped in memories of a traveling magic troupe from her childhood.

The chaotic marketplaces, unfamiliar produce, and foreign dialects intoxicate and overwhelm her. Yet, beneath the marvel lies a tension: Aoyama is not an ordinary tourist, but a Japanese writer invited under the pretext of promoting the empire’s Southern Expansion Policy.

Her refusal to accept the politically loaded offer from a magazine in favor of a more literary invitation from the women’s organization Nisshinkai marks the start of her resistance to imperial co-optation.

Her early days in Taiwan are frustrating. The meals prepared by her hosts are Japanese-style, a sanitized version of local cuisine, symbolic of the colonial masking of native culture.

Her persistent hunger—for food, for understanding, for something authentic—becomes a metaphor that threads throughout the narrative. Assigned to her is a civil servant named Mishima, whose stiff demeanor and formal kindness create more distance than connection.

The real transformation begins when Aoyama meets Chizuru, or Chi-chan, a young Taiwanese woman hired to be her interpreter.

Chi-chan is everything Aoyama’s official hosts are not: calm but sharp, respectful yet assertive, and a fluent bridge between Japanese and Taiwanese cultures. She introduces Aoyama to the true rhythms of the Island—its dialects, flavors, social complexities, and historical scars.

Their bond quickly becomes the core of the memoir, shifting the focus from exotic landscapes to the textures of intimacy and mutual discovery. Chi-chan’s teaching extends beyond translation.

She exposes Aoyama to the distinctions among local ethnic groups—Hoklo, Hakka, and Indigenous communities—and offers unspoken lessons in dignity and survival under a colonizing regime.

As they spend time together, their friendship deepens in the kitchen and on street corners, while also navigating unspoken power dynamics. Aoyama’s fascination with Chi-chan’s cooking reflects not just her desire to eat but her longing to understand.

Dishes like bí-thai-b k and muâ-ínn-thng are not merely local recipes; they are culinary testaments to Chi-chan’s labor, her history, and her quiet resistance. Initially, Chi-chan refuses to eat at the same table, still bound by her sense of hierarchical propriety.

But the formality gradually dissolves, and with it, so does the barrier between colonizer and colonized.

Chi-chan’s backstory is gradually revealed. Born to a concubine in the prestigious Ō family, she grew up on the margins of privilege.

Her education and professional accomplishments are marred by her social status, and her current position as an interpreter was secured through a half-sister’s influence. Her future, too, is dictated by familial duty—she is set to marry a Mainlander man in an arrangement that serves her family more than her.

These revelations expose a contrast with Aoyama, who clings to her personal autonomy and creative freedom with almost reckless pride. Yet, despite the disparities, the women find a fragile equality in shared meals and vulnerable conversations.

Later chapters focus on the emotional tension embedded in their relationship. A particularly meaningful section involves their preparation of a loach hotpot and Chi-chan’s triple curry dish.

These meals symbolize their emotional dance—caring gestures layered with unspoken desire, resistance, and resignation. Aoyama attempts to pierce Chi-chan’s emotional armor, seeking to truly understand her, but the latter deflects with wit and distance.

Her assertion that an interpreter “never reveals her secrets” is more than professional—it is her personal credo. This guardedness frustrates Aoyama, whose own feelings increasingly edge toward romantic affection.

The metaphor of wild ginseng appears as a crucial motif—beautiful and medicinal, yet often mistaken for something else and undervalued. Chi-chan compares herself to the plant, subtly conveying her perception of being misunderstood and overlooked.

Aoyama insists on her worth, calling her a pearl, but Chi-chan gently rebuffs the praise, emphasizing the power in self-acceptance rather than social validation. These moments reveal the emotional asymmetry between them.

Aoyama yearns for a bond that defies cultural and gendered roles, while Chi-chan navigates within those roles with quiet resilience.

The final arc of the narrative marks a sobering shift. Aoyama’s idealistic view of her stay in Taiwan collapses under the weight of disillusionment.

She grows depressed, struggles to write, and becomes increasingly aware of her own complicity in the colonial system. Her argument with Mishima crystallizes this realization.

He accuses her of moral inconsistency, of being self-righteous without true understanding. The critique wounds Aoyama and catalyzes her introspection.

She begins to see that her admiration of Taiwan’s people and culture had, at times, been laced with unconscious superiority.

Determined to make amends, she embarks on a walk—both literal and symbolic—from her residence in the elite Kawabata district to Chōkyōshitō, where Chi-chan lives. The reunion is awkward but honest.

They share a candid exchange outside a general store, in which Aoyama offers a heartfelt apology—not just for her personal missteps, but for her entire outlook. Chi-chan, though composed, confesses that she never truly viewed Aoyama as a friend, even though she cherished their time together.

The painful truth hangs between them, but so does a newfound clarity. They might never be equals in the eyes of society, but they shared something genuine—however flawed, however fleeting.

In their final moments together, they share a simple bowl of fruit and jelly ice. The dessert, cool and sweet, becomes a symbol of their fragile reconciliation.

It melts quickly, much like the window of their closeness, yet its taste lingers. The story concludes on this note of emotional ambivalence—full of loss, insight, affection, and a fragile hope that even within systems of hierarchy and injustice, people can still meet, understand, and care for one another, if only for a moment.

Taiwan Travelogue is ultimately a story of awakening—not just to another culture, but to one’s own limitations, prejudices, and capacity for growth. It is a memoir of encounters that are both deeply personal and quietly political, told with tenderness, self-awareness, and hard-won grace.

Characters

Aoyama Chizuko

Aoyama Chizuko emerges as a deeply introspective and passionate figure at the heart of Taiwan Travelogue, whose character arc reflects a dynamic interplay between cultural immersion, personal awakening, and the weight of colonial complicity. As a Japanese writer arriving in Taiwan under the Empire’s shadow in 1938, she begins her journey burdened with both privilege and curiosity.

Her initial lens is one of nostalgia and exoticism, shaped by youthful memories of spectacle and enchantment. However, she is neither blindly complicit nor ideologically aligned with the Empire’s goals—when offered funding by a magazine for propagandist purposes, she refuses, signaling her preference for artistic independence over political co-option.

This act of resistance becomes foundational to her identity throughout the travelogue, portraying her as someone striving for authentic engagement even while wrestling with the unearned advantages of her position.

Aoyama’s most compelling evolution unfolds through her sensory and emotional encounters with Taiwan. She seeks not just to observe but to taste, feel, and understand the place on its own terms, frustrated by the curated colonial experiences arranged by hosts like Mishima.

Her longing for unmediated Islander food is more than culinary—it is symbolic of her craving for cultural sincerity. Her emotional spectrum deepens with the entrance of Chi-chan into her life, whose grace, resilience, and intellect both challenge and inspire Aoyama.

Through this relationship, Aoyama begins to shed the detached role of outsider-observer and allows herself to become vulnerable, questioning not only her views of the colonized other but also her assumptions about friendship, intimacy, and power. Her affection for Chi-chan, often tinged with unspoken romantic desire, reveals an aching need for connection and a struggle with emotional boundaries, especially as Chi-chan quietly resists full reciprocity.

As the story unfolds, Aoyama confronts her own elitism and self-centeredness, particularly during moments of tension and miscommunication. Her emotional descent into melancholy and purposelessness while residing in Taiwan reflects an existential crisis that culminates in self-awareness.

The climactic confrontation with both Mishima and Chi-chan forces Aoyama to reckon with her identity not just as an artist, but as a colonizer navigating moral ambiguity. Her eventual apology to Chi-chan is an act of humility and transformation—one that does not erase past missteps, but rather opens the door for a fragile, hard-earned reconciliation.

Aoyama ends her journey not triumphant, but altered—less certain, more compassionate, and deeply aware of the emotional and historical terrain she has traversed.

Chizuru “Chi-chan” (Ông Tshian-hóh)

Chi-chan is a quietly formidable character whose grace, resilience, and cultural fluency anchor the emotional and thematic core of Taiwan Travelogue. Introduced as Aoyama’s interpreter, Chi-chan transcends the constraints of that title through her complex inner world and the emotional impact she has on the protagonist.

Born into the Ō family as the daughter of a concubine, her status is socially compromised despite her education and poise. This duality—of being both privileged and marginalized—colors her entire existence and shapes her interactions.

She possesses a nuanced understanding of both Taiwanese and Japanese cultures, navigating the fraught space between colonizer and colonized with diplomatic detachment, quiet strength, and occasional bursts of dry wit.

Chi-chan is marked by her emotional restraint and a deep-seated sense of duty. Initially insistent on maintaining professional decorum—refusing to eat at the same table as Aoyama or to abandon formal address—she gradually allows herself to soften.

Yet even as she permits glimpses of vulnerability, she never fully relinquishes control over her inner life. Her hesitance to reciprocate Aoyama’s overtures, whether personal or romantic, is not coldness but a shield of self-preservation.

Chi-chan is acutely aware of power imbalances and the cost of emotional transparency in a colonial context. Her reflections on being like wild ginseng—misunderstood, undervalued, and misidentified—reveal a deep poetic awareness of her own worth and invisibility.

Her role as a culinary guide and cultural bridge is crucial, not only for Aoyama’s journey but for the narrative’s sensory and emotional texture. Chi-chan’s cooking—especially labor-intensive dishes like jute-leaf soup—serves as a medium for connection, resistance, and expression.

Even as she outwardly deflects Aoyama’s probing, she reveals herself in coded ways: through stories, recipes, and quiet acts of care. Her decision to give Aoyama a kimono, and her continued use of polite distance, underscore the bittersweet nature of their bond.

While she may not embrace Aoyama as a friend in the conventional sense, she acknowledges the emotional labor and meaning of their time together. In the end, Chi-chan emerges not as a passive interpreter but as a fully realized individual, quietly reclaiming dignity and asserting boundaries within a world that seeks to define her otherwise.

Mishima

Mishima, the bureaucratic civil servant assigned to accompany Aoyama, serves as a foil to both her and Chi-chan, representing the impersonal machinery of Empire. His demeanor is consistently polite, professional, and emotionally distant, maintaining the boundaries expected of a colonial official.

To Aoyama, his rigid adherence to protocol and his inability—or unwillingness—to facilitate authentic local experiences becomes a source of quiet frustration. While never overtly antagonistic, Mishima symbolizes the subtle yet pervasive mechanisms of cultural control, shaping how Japan’s colonized territories are experienced by visiting elites.

His tendency to guide Aoyama through sanitized versions of Taiwanese culture mirrors the broader imperial practice of erasing native authenticity in favor of palatable spectacle.

Yet Mishima is not without insight. In a pivotal exchange, he confronts Aoyama with a brutally honest critique of her intellectual inconsistency—accusing her of selective morality, of praising or criticizing the colonial order based on personal sentiment rather than ethical clarity.

This moment stings precisely because it is true, marking a turning point in Aoyama’s internal reckoning. Mishima thus functions not just as a passive agent of the state, but as an ideological mirror, exposing Aoyama’s blind spots and forcing her to confront the limits of her self-perceived righteousness.

His character remains emotionally opaque, but his impact on the narrative is profound—reminding readers that complicity often wears the mask of civility and that even thoughtful dissent must contend with its own contradictions.

The Ō Family

Though they do not appear directly, the Ō family looms large in the background of Chi-chan’s narrative. They embody the complex social stratifications within Taiwanese elite society under Japanese rule.

As a prestigious household, their treatment of Chi-chan reflects entrenched hierarchies not only shaped by colonial power, but also by gender and lineage. Chi-chan’s status as the daughter of a concubine relegates her to a subordinate role despite her education and accomplishments.

Her path to employment as an interpreter is made possible only through the intercession of her half-sister—an act that underscores both the family’s influence and their condescension. The Ō family serves as a shadowy symbol of societal expectations, familial obligation, and the pervasive stigmas that Chi-chan must navigate daily.

Their presence reinforces one of the narrative’s most poignant themes: the quiet resilience required to maintain dignity in a world structured to deny it.

Themes

Cultural Translation Through Sensory Experience

Aoyama Chizuko’s journey in Taiwan Travelogue is framed through the acute awareness of her senses, and this becomes the primary mode through which cultural understanding is explored. Taiwan, at first, is a series of smells, tastes, sounds, and visual surprises that overwhelm and excite her.

Her repeated references to unfamiliar vegetables, sweet desserts, and pungent herbs are not merely observational; they reflect her deep desire to comprehend Taiwan beyond language or policy. Chizuko’s hunger—both literal and symbolic—propels her narrative.

The craving for “real” Islander food and her dissatisfaction with Japanese-style substitutions embody her resistance to imperial filtering. Food here becomes a tactile symbol of authenticity, something she longs for in an environment shaped by colonial agendas.

Each meal that carries local flavor brings her closer to understanding Taiwan as it truly exists beneath imperial surfaces. Her relationship with Chi-chan and the way they share and prepare meals together represents a mutual decoding of each other’s worlds.

Through curry, ginseng, jute-leaf soup, and fermented seafood, a new lexicon is established—one where dishes tell stories that history books cannot. This culinary dialogue humanizes the colonized experience and bypasses institutional intermediaries, showing how something as mundane as food can become a bridge across vast cultural and political divides.

Colonial Power and Soft Resistance

The memoir subtly but sharply critiques the pervasive structures of Japanese colonialism in 1930s Taiwan, highlighting both overt systems of control and the more insidious, everyday forms of domination. Chizuko’s initial invitation by a magazine aligned with Japan’s expansionist agenda sets the political context.

Her refusal to write propaganda indicates an early assertion of autonomy, but she soon realizes that colonialism shapes even the most mundane aspects of daily life: the meals she’s served, the conversations she’s allowed to have, and the itinerary she’s given. The polite distance maintained by figures like Mishima and the “well-meaning” suffocation of her hosts are not merely social quirks—they are mechanisms of soft control.

Chi-chan’s situation exemplifies how deeply colonial hierarchies penetrate: despite being educated and articulate, she is treated as a cultural intermediary at best, a second-class citizen at worst. Her refusal to eat at the same table as Aoyama underscores how internalized this order has become.

Yet resistance exists in the everyday. Chi-chan’s quiet refusal to be pitied, her subtle redirections of conversations, and her dignified navigation of her constrained position embody a kind of soft resistance.

Aoyama’s growing awareness of these injustices, and her eventual decision to walk across the city to seek reconciliation, marks a slow but meaningful shift away from her previous passive complicity.

Gender, Class, and Structural Marginalization

The emotional and political arc of the narrative hinges on the sharp contrasts between Aoyama and Chi-chan, two women shaped by different ends of colonial and social hierarchies. Aoyama, a respected Mainlander writer, moves through Taiwan with relative freedom, supported by her fame and Japanese citizenship.

Chi-chan, by contrast, is a daughter of a concubine in a prominent Taiwanese family, caught in the liminal space between privilege and marginalization. Her social mobility is constrained by birth, gender, and colonial definitions of worth.

Despite her intelligence and education, her interpreter role is conditional, granted only through familial strategy, and her impending marriage serves as a transactional arrangement rather than a personal aspiration. The text scrutinizes how gendered power operates differently under colonialism: Aoyama’s resistance to marriage and embrace of literary life are celebrated, while Chi-chan must suppress her intellectual dreams and emotional desires.

Their friendship is a crucible where these differences are tested, questioned, and sometimes reaffirmed. Aoyama pushes for equality, insisting on shared meals and rejecting hierarchical titles, but Chi-chan responds with caution, shaped by a lifetime of knowing her place.

The act of preparing and sharing food becomes a battleground for these tensions: who serves, who eats, who chooses the menu. Their emotional exchanges—especially the painful realization that their friendship was not entirely mutual—are embedded in these structures, exposing how patriarchy and classism fracture even the most intimate human bonds.

Emotional Distance and the Mask of Politeness

One of the most poignant emotional dynamics in Taiwan Travelogue is the persistent asymmetry in emotional vulnerability between Aoyama and Chi-chan. Aoyama is expressive, impulsive, and often emotionally needy.

She reaches out, confesses affection, probes for emotional truths, and longs for open declarations of closeness. Chi-chan, by contrast, remains measured, polite, and intentionally opaque.

Her refusal to respond directly to Aoyama’s emotional offerings is not an absence of feeling but a form of self-protection. She wears what Aoyama calls a “Noh mask”—a metaphor for the cultural expectation of stoicism and indirect communication.

This emotional reserve is not just personal but emblematic of a broader pattern of colonial interaction, where Islanders were taught to remain composed, deferential, and inscrutable. Chi-chan’s frequent deflections, polite smiles, and references to duty rather than desire speak volumes about how emotional expression is policed by social role and cultural expectations.

Even moments of intimacy—like shared curry or giving a kimono—are framed through ritual rather than spontaneity. The eventual reconciliation scene underscores this theme: Chi-chan acknowledges Aoyama’s apology but maintains her boundaries.

Her refusal to say “I considered you a friend” is not cruel but clarifying. It reveals that emotional truth, under colonial constraint, can be both sincere and strategic, compassionate yet firm.

Their parting, over a bowl of jelly ice, is emblematic of this contradiction: sweet, melting, beautiful, and impermanent.

Food as Memory, Language, and Political Commentary

Throughout the narrative, food serves not merely as a cultural artifact but as a complex narrative device loaded with emotional, political, and historical meaning. Aoyama’s fixation on dishes like bí-thai-b k, muâ-ínn-thng, kiâm-n g-ko, and curry reflects her search for unfiltered experiences in a colonized space.

Food becomes the clearest vocabulary for understanding Taiwan, a medium through which people reveal themselves when words fail or discretion is necessary. Each dish is wrapped in layers of personal and political memory: the jute-leaf soup represents the bitterness and patience of Chi-chan’s upbringing; wild ginseng mirrors the hidden value of Taiwan’s people and culture, often dismissed or mistaken by the imperial center; curry becomes a platform for emotional confession masked as culinary discussion.

These meals are also performative—they allow characters to speak indirectly, to bond without confrontation, to assert identity without rebellion. Aoyama’s emotional state often fluctuates with her culinary encounters: alienation when served Japanese meals by colonial hosts, warmth and intimacy when cooking with Chi-chan, existential clarity when chewing a gravel-like sponge cake.

In each case, the food consumed is a symbol of power—who cooks, who eats, what ingredients are used, and what memories are invoked. The simple act of eating together becomes a radical act of recognition and equality, revealing how food can resist, remember, and reimagine social boundaries.