Tartufo Summary, Characters and Themes | Kira Jane Buxton

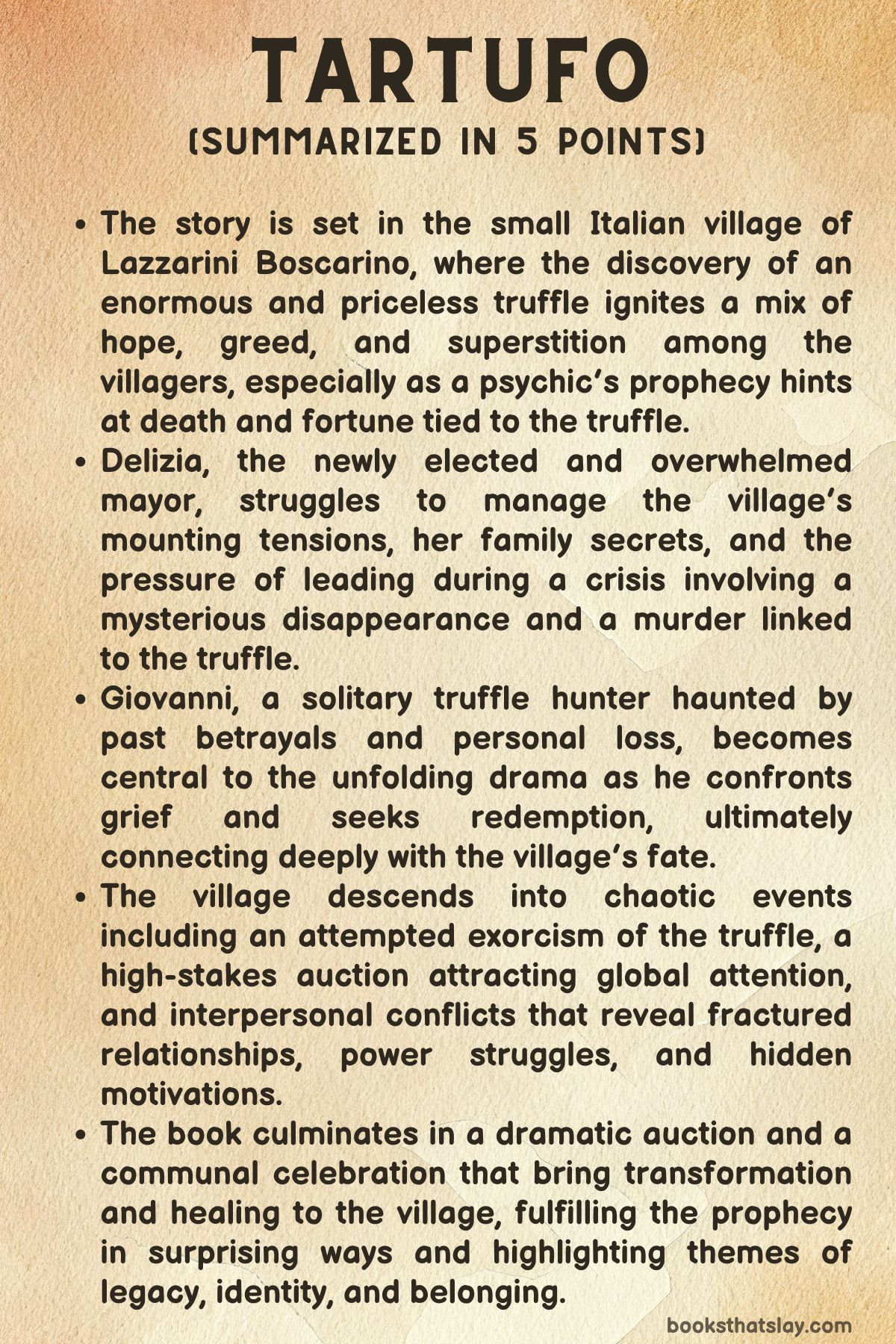

Tartufo by Kira Jane Buxton is a vivid, character-rich novel set in the slowly crumbling yet enchantingly stubborn village of Lazzarini Boscarino, nestled in the Italian countryside. It blends sharp humor, emotional complexity, and an intimate sense of place to explore themes of legacy, love, grief, community, and nature’s quiet omnipresence.

Told through multiple perspectives—ranging from eccentric villagers to truffle-hunting dogs and even a wandering bee—the book offers a panoramic yet deeply personal look at a community on the edge of extinction. Yet rather than wallow in despair, the narrative champions resilience, interconnectedness, and the surprising beauty that can emerge from decay.

Summary

In the fading village of Lazzarini Boscarino, where boarded-up storefronts outnumber residents and nostalgia clings to every cobblestone, Bar Celebrità stubbornly persists. Its owner, Giuseppina, is as flamboyant and loud as the espresso she serves—her boldness a shield against the pain of being abandoned by her daughter and overlooked by the world.

Giuseppina, armed with her unapologetic sensuality and hopeful interpretations of a psychic’s prophecy, becomes a symbol of resistance against irrelevance. She believes that a visitor, a death, and a fortune will revive her hometown.

When a confused Swedish couple enters her bar and then flees in panic, her hope flickers, but a boar carcass and twenty euros hint that the prophecy may yet hold weight.

The prophecy’s second act begins with Delizia, the newly instated and deeply anxious mayor, who carries the burden of a hidden truth. Her deceased father, the former mayor, embezzled the funds that could have saved the village.

Delizia, once an escapee from village life, now returns with the impossible task of salvation, all while hiding the painful discovery of her father’s corruption. Her first town meeting dissolves into confusion and nostalgia, punctuated by jokes and chaos.

Still, she clings to the dream of tourism and renewal, refusing to shatter her villagers’ belief in a better future.

Far from the bustle of the comune, Giovanni, a solitary truffle hunter, sets out with his dogs, Aria and Fagiolo. Haunted by betrayal from fellow hunters and long-simmering grief over the loss of his partner Paolo, Giovanni’s true solace lies in the forest and in the scent-based communication with Aria.

Through her perspective, the reader glimpses the woodland’s magic—where memory, decay, and time commingle in earthy perfumes. A remarkable discovery—a colossal white truffle unearthed by Aria—catapults Giovanni into a state of shock.

This is no ordinary fungus; it’s a symbol of both redemption and exposure. The truffle has the power to alter his future, and the village’s, irrevocably.

Meanwhile, the village’s intergenerational connections unfold through Vittoria, a young girl tied deeply to her grandmother, Nonna Amara. Together they find meaning in food, memory, and the tactile world of taste and ritual.

Vittoria, torn between the simplicity of her grandmother’s love and the emotional distance of her mother, is driven by guilt over a series of accidents she believes she caused—a lost brooch, a missed warning before a deadly landslide. These anxieties become emotional lodestones, shaping her perceptions of safety and loss.

Nature serves both as backdrop and character: a recent landslide scars the mountainside, reminding all of the environment’s destructive force. Yet nature also births the miraculous truffle and nurtures unlikely joys, such as Nonna Amara’s thriving post-catastrophe garden.

The narrative balances the duality of nature—its power to wound and to heal.

A parallel tension brews inside the village castle, transformed into the epicenter of an international media storm. The truffle will be auctioned, and with it, the hopes of Lazzarini Boscarino.

Journalists, culinary elites, and opportunists converge. Among them, a honeybee flits through banquet halls and kitchens, observing human absurdity with dispassion, drawn only by instinct and sugar.

Her presence becomes an elegant metaphor for nature’s indifference and wisdom amidst human frenzy.

Giovanni, still distrustful and deeply private, is devastated when his dog Fagiolo and Jeep are stolen. The betrayal fractures him.

After a chaotic and desperate pursuit in a tiny Piaggio Ape, Fagiolo is recovered, but Giovanni’s faith in the village and its people is broken. He withdraws again, the truffle’s promise now tainted by human interference and greed.

Delizia, grappling with both the political pressures of the auction and her own emotional landscape, recalls the painful memories of her wedding—once a joyful village event marred by her father’s rejection. As she tries to hold the community together, Sofia, a beloved resident, vanishes.

Hopes that she fled willingly are dashed when Giovanni stumbles upon her lifeless body in the woods. Her death cuts deeply, exposing how thin the line between eccentricity and tragedy can be in such a close-knit place.

The truffle, hidden for safekeeping in the church crypt, is stolen. The betrayal deepens.

Yet the show must go on. The Sotheby’s-led auction launches into theatrical excess, featuring inflated egos and surreal villagers-turned-spectacle.

As bidders compete with millions of euros, the narrative’s center trembles under the weight of absurdity and desperation. Ricco, a wealthy daredevil, wins the auction, but triumph is short-lived.

Vittoria, hoping to right her own perceived wrongs, crashes the event on a stolen Vespa, inadvertently triggering chaos. Rico Valentino, a smarmy rival truffle mogul, is revealed as the real thief—and in the fracas, the truffle is destroyed.

The physical truffle is gone, but in its ruin, truths emerge. Giovanni comforts the distraught Vittoria, reminding her that she is loved not for what she fixes or saves, but for who she is.

Nonna Amara affirms this with quiet warmth. Their message echoes through the wreckage: the truffle was never the treasure.

Love, memory, community—these are the true riches.

In a final gesture of compassion, Delizia, aided by her community, saves the village donkey, Maurizio, from impaction colic. As they gather to celebrate his recovery and birthday, a rare wolf appears, a ghostly emblem of survival, strength, and belonging.

Delizia shares a quiet, hopeful moment with Leon, while in the background, a filmmaker begins to capture their village’s eccentric charm.

Though the truffle is gone, something deeper has been recovered. Bonds are repaired.

Secrets are brought to light. And with a whisper of a plan for UNESCO recognition, Delizia steps forward with new resolve.

Tartufo ends not with fame or riches, but with something more enduring: a recommitment to place, people, and shared resilience.

Characters

Giuseppina

Giuseppina stands as the emotional and comedic heart of Tartufo. She is a vivacious, theatrical woman whose flamboyant nature conceals a deep ache of abandonment and loss.

Her body is described as voluptuous and unruly, much like her spirit, which refuses to submit to the creeping decay of the village of Lazzarini Boscarino. Despite being surrounded by crumbling infrastructure and dwindling life, Giuseppina clings fiercely to hope, beauty, and sensuality.

Her bar, Bar Celebrità, is less a business and more an altar to the possibility of revival—of the village and of her own relevance in a world that increasingly seems to have passed her by. Her passionate longing to resurrect vitality in the village is both comic and tragic.

She becomes a prophet, a seductress, and a mother figure all at once, embodying the contradictions of a place suspended between death and dream. Her belief in the psychic prophecy reflects her desperate clinging to magic in a world governed by indifference.

Even her outlandish gestures, such as flashing tourists, are rooted in an almost religious zeal for renewal. Giuseppina is more than a character; she is a force of will.

Delizia

Delizia is a woman pulled taut between personal guilt and public responsibility. As the newly appointed mayor of Lazzarini Boscarino, she embodies the modern tragedy of inherited failure.

Smart and neurotic, she is burdened by the discovery that her father, the late mayor, embezzled funds meant to save the village. Delizia’s return to the town is not triumphant but tentative, steeped in shame and uncertainty.

She is haunted by her father’s betrayal and unable to fully reveal the truth to the villagers who raised her with love and eccentricity. Her internal conflict manifests in moments of comic disorder, such as the botched comune meeting, but these are undercut by a genuine tenderness for the people and place she serves.

Delizia’s arc is one of atonement, both for her father’s sins and her own absence. She is the narrative’s quiet moral compass, driven not by ego but by a sincere desire to salvage something sacred from the wreckage.

As the story unfolds, her actions—whether saving a donkey or confronting grief—reveal a deeply layered humanity grappling with how to lead amidst ruin.

Giovanni

Giovanni is a character steeped in memory, solitude, and reverence for the natural world. An aging truffle hunter with a weathered heart, he carries the scars of betrayal, homophobia, and love lost.

His connection to his dogs, especially Aria, is more spiritual than practical—she is his anchor, confidante, and lifeline. Giovanni is a man estranged from society but deeply attuned to the earth’s rhythms.

His mistrust of others, particularly in the competitive world of truffle hunting, stems from real wounds: poisoned dogs, stolen finds, and accusations from rivals. Through the eyes of Aria, his life becomes poetry—scent, soil, and silence narrate his existence.

His discovery of the massive white truffle represents a culmination of years of suffering and patience. The truffle is not just a prize; it is a resurrection of Paolo’s love, a symbol of enduring devotion unearthed from the dark.

When he later finds Sofia’s body and retreats from the village, Giovanni embodies the sorrow of a man who has given all to a place that keeps taking. And yet, he returns, not for applause but for connection, proving that even the most wounded hearts can re-enter the world.

Aria

Aria is more than a dog; she is a sentient force and an embodiment of memory and intuition in Tartufo. As Giovanni’s seasoned truffle-hunting companion, Aria’s bond with him transcends the animal-human dynamic—she understands his moods, his grief, and his needs with a wisdom that is nearly mythic.

The narrative’s decision to shift into her perspective renders her a character of immense depth, capable of interpreting the world through scent in ways that reveal emotional and historical truths. She is calm, precise, and nurturing, standing in stark contrast to her younger counterpart, Fagiolo.

Aria becomes the quiet guardian of Giovanni’s past and the key to his future when she uncovers the legendary truffle. Her death, implied later in the narrative, marks not just the passing of a pet but the loss of a sacred bond.

She is the novel’s most eloquent emblem of loyalty, love, and the spiritual intelligence of nature.

Fagiolo

Fagiolo is the embodiment of joyful chaos. As Giovanni’s young and impulsive dog, he is all energy and unpredictability.

His exuberance disrupts hunts, swallows precious truffles, and injects comic relief into the narrative’s darker currents. Yet Fagiolo is not merely comic fodder—he symbolizes the unruly vitality of life that persists even amidst grief.

He provides Giovanni with a reason to stay tethered to the world, a reminder that not all bonds are built on memory and sorrow. Fagiolo’s innocence and affection offer healing, and his eventual recovery after being stolen restores faith in the possibility of joy after devastation.

His presence complicates Giovanni’s mourning for Aria, forcing him to acknowledge that love—however chaotic—continues.

Vittoria

Vittoria is a poignant portrait of childhood shaped by absence, longing, and fierce love. Caught between a distant mother and an idealized father she has never known, she clings to her grandmother Nonna Amara as her emotional anchor.

Through Vittoria, the novel captures the innocence of magical thinking: her belief that attention and vigilance can prevent disaster is a deeply childlike response to trauma. Her guilt over lost objects and natural disasters reflects a heart that feels too responsible for the chaos of the world.

Yet she is also brave, stealing a Vespa and disrupting the truffle auction in a desperate bid to do good. Her tears at the broken truffle are not just for the ruined fungus but for a world that seems to crumble no matter how tightly she tries to hold it together.

In Vittoria, we see the heartbreak of growing up and the first steps toward understanding that love is not about control, but presence.

Nonna Amara

Nonna Amara is a figure of profound grounding and grace. She offers Vittoria the love and stability that the girl’s mother fails to provide.

Amara’s rituals—cooking, gardening, singing—are acts of resilience, infusing life into the ruins of her home and community. She is the keeper of memory, the nurturer of tradition, and the quiet philosopher of the narrative.

Her joy in small, imperfect things—sage overtaking the garden, deer-nibbled apples—speaks to her ability to find hope in destruction. Even after losing her house to a landslide, she tends her broken garden with tenderness.

Nonna Amara’s love is unconditional, a quiet force that shapes Vittoria’s understanding of herself and the world. Her presence elevates the domestic into the sacred, anchoring the novel’s broader themes of memory, grief, and rebirth in the soil of lived experience.

Sofia

Sofia is an absent presence whose disappearance haunts the village like a whispered secret. Though she appears mainly through others’ memories, she is a figure of love, loss, and unresolved pain.

To Delizia, Sofia is a friend, a witness to formative moments, and perhaps a representation of an alternate life unlived. Her death in the woods marks a turning point in the novel, the shattering of any remaining illusions that this story might stay within the bounds of comedy and charm.

Sofia’s body becomes a grim symbol of how secrets—both personal and communal—fester in silence. Her absence is felt most in the aching spaces of grief and in the quiet ways the village tries to carry on.

Delizia’s Father (Mayor Benigno)

Mayor Benigno is a ghost haunting his daughter’s every decision. Though dead, his legacy lives on in the corruption he left behind—embezzled aid, broken trust, and a village on the brink.

To Delizia, he is a complex figure: a man she loved, a leader she once believed in, and the architect of her greatest shame. Her inability to confess his crimes reveals the depth of her emotional entanglement with him.

He represents the weight of inherited sins, the burden of family failure, and the painful knowledge that even those we idolize can falter. His absence, like Sofia’s, reshapes the village, not through death alone but through the damage he left behind.

Rico Valentino

Rico Valentino is the embodiment of greed and artifice in Tartufo. As a rival from Borghese Tartufi, he slithers into the village under a guise of professionalism but ultimately reveals himself to be the truffle thief who shatters the prize at the auction.

His betrayal punctures the village’s fragile bubble of hope, reducing their symbol of salvation to broken pieces. He is a necessary villain, representing how commodification and ambition corrupt even the most sacred pursuits.

His presence in the narrative is brief but catastrophic, proving that not every outsider comes with good intentions.

The Honeybee

The honeybee is a quiet, omniscient observer threading together the chaos of the human world. As she buzzes through banquet halls, kitchens, and auctions, she becomes a symbolic counterpoint to the narrative’s heavier themes.

She is both literal and allegorical—seeking sweetness in a crumbling world, doing her part for the hive, and bearing witness to both absurdity and grace. Her flight patterns mirror the story’s own meandering structure, revealing how the smallest, most overlooked creature can hold the most panoramic perspective.

Her journey home, with sugar in tow, is a quiet triumph—a testament to the persistence of beauty and purpose amidst human folly.

Themes

Decay and Resilience of Place

Lazzarini Boscarino is a village defined by decay, abandonment, and inertia. The physical signs of disintegration—shuttered restaurants, overgrown gardens, crumbling crypts—reflect a community on the brink of extinction.

Yet, despite the collapse, there remains a defiant, sometimes absurd sense of resilience. This is embodied most vividly in Giuseppina, who refuses to surrender to the slow death of her beloved home.

Her flamboyance, vulgarity, and theatrical antics aren’t simply for show—they are acts of protest against the creeping silence of a vanishing place. Similarly, Delizia’s return to the village, despite her shame and knowledge of her father’s corruption, signals an attempt at restoration.

Her plan to reinvigorate the economy through tourism is a last-ditch effort to save something that might already be unsalvageable. In these attempts, there is both comedy and tragedy.

The absurdity of flashing tourists or holding town meetings in closed restaurants underlines how far the village has fallen, but also how stubbornly its people cling to what’s left. Giovanni’s relationship with the forest and truffle hunting offers another form of endurance—one grounded in ritual, memory, and communion with the land.

Even Nonna Amara’s ruined garden becomes a symbol of quiet resistance, her joy in apple-gnawed fruit and wild sage revealing that beauty can still emerge in chaos. The village’s identity becomes inseparable from its struggle to endure.

And through every failed revival or fleeting hope, Tartufo reveals that decay may be inevitable, but the will to resist it—however messy or misguided—is what makes life meaningful.

Generational Trauma and Unspoken Legacies

The story is haunted by the secrets, shame, and unfinished business passed down from one generation to the next. Delizia’s discovery of her father’s embezzlement casts a long shadow over her attempts to lead with integrity.

She cannot publicly atone for what he did, yet she bears the emotional weight of his betrayal. Her silence is both a survival mechanism and a source of internal torment.

Giovanni’s memories of Paolo and his father’s rejection are another form of inherited pain. The scars left by cruelty and homophobia are not just emotional—they shape the entire architecture of Giovanni’s adult life, from his solitude to his reverence for the forest.

For Vittoria, childhood guilt takes on mythic proportions. She believes herself responsible for her grandmother’s losses, attributing enormous power to her vigilance and attention, as though love could prevent catastrophe.

These characters are all, in different ways, grappling with what they’ve been handed: financial ruin, emotional neglect, cultural silence, and buried truths. The past is never just the past—it invades the present, shaping choices, relationships, and self-perception.

Yet the story does not frame this as purely tragic. In the act of remembering, confessing, or choosing to return despite shame, there is an opportunity for new beginnings.

By placing these struggles alongside elements of humor and surrealism, Tartufo resists romanticizing suffering, but it honors the quiet acts of endurance that arise in its aftermath.

The Power and Peril of Obsession

Throughout the narrative, obsession emerges as both a driving force and a dangerous compulsion. Giovanni’s life is ruled by the hunt for truffles—not just for their monetary value but for their ability to connect him to lost love, purpose, and beauty.

His care for Aria is obsessive in its precision, born out of fear, love, and past trauma. When Fagiolo disappears, Giovanni unravels, chasing down the Jeep with wild, reckless energy.

The truffle itself becomes a dangerous totem. It is no longer merely a delicacy but a catalyst for economic salvation, personal redemption, and, ultimately, ruin.

Its theft and destruction provoke a communal reckoning, forcing the village to confront what they’ve sacrificed in their collective desire for fame and fortune. Vittoria’s desperate actions—stealing a Vespa, crashing the auction—stem from her intense wish to fix something for her nonna, to matter in a world where she feels like an afterthought.

Even the honeybee, endlessly circling the sugar-laden banquet, is a subtle metaphor for the obsessive cycles of human ambition and labor. The danger lies not in passion itself, but in the way it blinds characters to the consequences of their choices.

The village risks its fragile unity by placing too much faith in a single prize. The emotional cost of obsession is high, but it also illuminates the depth of the characters’ desires—for recognition, healing, belonging.

In Tartufo, obsession is not villainized; rather, it’s shown as a potent force that can either elevate or destroy, depending on what one is willing to abandon in pursuit of a dream.

The Fragility and Strength of Community

The village is a paradoxical entity—simultaneously ridiculous and resilient, fractured and devoted. Its members are loud, stubborn, often absurd in their behaviors, yet bound by invisible threads of affection and memory.

The comune meetings, filled with petty complaints and farcical arguments, are more than comic relief; they reveal a community that knows itself intimately, in all its flaws. The villagers’ involvement in the auction preparations, despite their lack of experience or coordination, signals a desire to matter, to be part of something bigger.

Delizia’s connection to them is rooted not in duty, but love—love complicated by shame and guilt, but love nonetheless. Giovanni’s withdrawal from the community after betrayal underscores how delicate trust can be, and yet, his return to protect and comfort Vittoria marks a return to something larger than himself.

Even in moments of chaos, like the donkey’s medical emergency, the villagers come together without hesitation. The story resists idealizing the community, showing how easily envy, secrecy, and greed can fester.

Still, it insists that these same people, when confronted with loss or crisis, will show up for each other. The community’s strength lies not in its efficiency or morality but in its collective memory and stubborn refusal to fully let go.

The final scenes—Maurizio’s birthday celebration, Delizia’s quiet plans for UNESCO status—point to a cautious optimism. The village may never fully repair itself, but as long as its people continue to gather, remember, and forgive, it retains a pulse.

Tartufo ultimately argues that community is not about perfection but persistence.

Memory, Grief, and the Reclamation of Identity

Memory saturates every corner of the narrative—tangible in truffle-scented soil, in broken gardens, in whispered songs between grandmother and granddaughter. It is both a balm and a burden.

For Giovanni, memory is a pathway to Paolo, a reminder of love unmarred by shame. But it is also a source of sorrow, especially when paired with the knowledge of how much was lost due to his father’s rejection.

The forest becomes a sacred archive for him, a place where the past can be safely felt and where grief is not a hindrance but a companion. For Vittoria, memory is tied to identity formation.

Her understanding of herself is shaped by Nonna Amara’s stories, rituals, and validation. Through these memories, she pieces together who she is and who she wants to become, despite the absence of her father and the emotional distance of her mother.

Delizia, too, is wrestling with the past—not only her father’s crimes but the warmth and betrayal embedded in her wedding memories. Each character’s relationship to memory is fraught but essential.

Grief, in this story, is not a closed wound but a living force. It sharpens clarity, alters decisions, and deepens connections.

Even the destroyed truffle, an object of immense value and symbolic power, is memorialized not with despair but with grace and perspective. The act of remembering—honestly, painfully, and collectively—becomes a way for characters to reclaim their truths.

In Tartufo, memory is the soil in which identity takes root. Grief is not something to overcome, but something to carry with strength.