Tender is the Flesh Summary, Characters and Themes

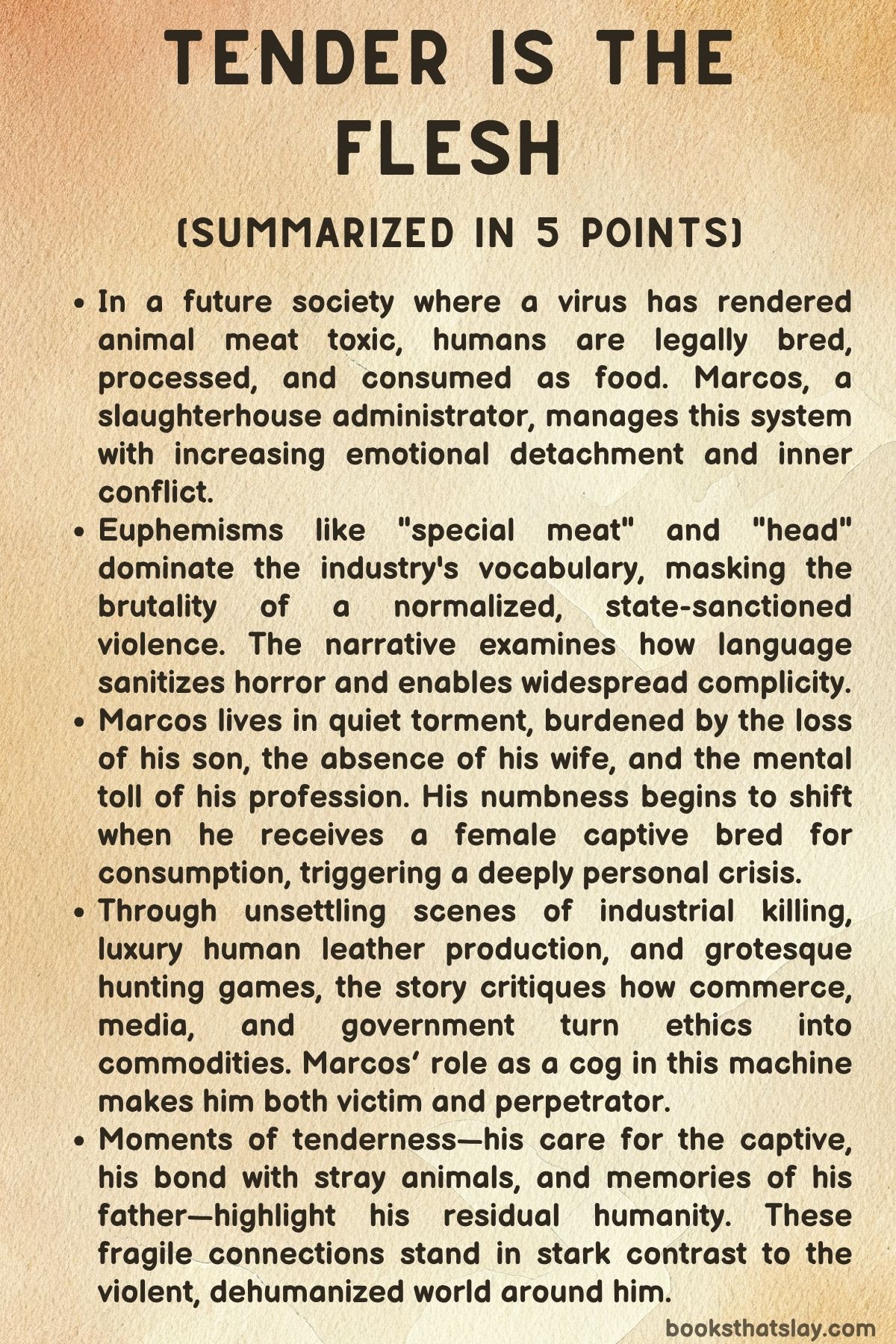

Tender is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica is a dystopian novel set in a future society where a virus has supposedly made all animal meat toxic, prompting governments to legalize the breeding, processing, and consumption of human beings. The narrative follows Marcos Tejo, a high-ranking employee in a meat processing plant, as he navigates this dehumanized world with a hollowed conscience and deep personal grief.

Through clinical language, institutional euphemisms, and intimate moments of contradiction, the novel explores themes of complicity, systemic violence, loss, and the erosion of empathy in the face of survival. It is a chilling examination of what happens when language, power, and ideology strip away humanity.

Summary

In the world of Tender is the Flesh, the slaughter of animals has been outlawed due to a virus that supposedly made all animal meat lethal to humans. In response, society has sanctioned the consumption of human flesh.

People labeled as “heads” are bred, fattened, and butchered in government-certified facilities. The transition has been made palatable through a carefully engineered lexicon of euphemisms and clinical detachment.

Marcos Tejo, the protagonist, works as the chief operations manager at one of the most elite processing plants, overseeing every part of the industry—from breeding farms and slaughterhouses to skin processing and quality control. Though outwardly professional and controlled, Marcos is deeply tormented by the ethical horror around him and the profound grief of having lost his infant son, Leo.

His wife, Cecilia, has emotionally withdrawn and moved away, unable to bear the loss. Marcos continues to exist in a state of emotional paralysis, torn between detachment and a suppressed yearning for connection.

At the plant, Marcos trains new employees and screens them for signs of either desensitization or moral resistance. One such recruit vomits at the sight of the carnage, while another eagerly absorbs the grotesque details.

These small observations allow Marcos to see the growing chasm between those who have adapted to this new order and those still haunted by vestiges of old morality. The factory floor is a mechanized space of horror, where human bodies are processed with the same cold efficiency as animals once were.

Nothing is wasted—skin becomes leather, organs are delicacies, and bones are rendered into decorative materials. Even the terminology has been adjusted to dehumanize: subjects are called “product” or “special meat,” and are measured by yield rather than personhood.

Marcos is gifted a live female “First Generation Pure” (FGP) by a grotesque supplier known as El Gringo. This FGP, bred entirely in captivity and certified for consumption, is bound and silent, and initially kept in Marcos’s barn.

Though he tells himself he will eventually “process” her, her presence stirs something unresolved in him. The unnamed woman becomes a mirror for his fractured conscience.

Her helplessness forces him to confront the void within himself, shaped by grief, alienation, and the moral rot of his profession. One evening, Marcos unties her.

She stays by his side, and instead of slaughtering her, he begins to care for her in small ways—washing her, feeding her, teaching her human behaviors. Eventually, he names her Jasmine.

Parallel to this relationship, Marcos must maintain his public face in the gruesome social order. He visits people like Urlet, a game preserve owner who organizes human hunting parties for elite clientele.

There are also religious institutions, like the Church of the Immolation, which views self-sacrifice and consumption of the human body as spiritual acts. These institutions further sanitize and commercialize horror, using ideological justifications to sustain the system.

As Marcos travels through this world—meeting with executives, witnessing brutal experiments in the Valka Laboratory, and seeing the slow mental collapse of other employees—he recognizes the total moral collapse around him.

Despite his resistance, Marcos cannot escape complicity. He regularly oversees mass killings, approves shipments, and even calculates which groups of “heads” are safe to eat based on origin and treatment.

His life is steeped in contradiction: he rescues puppies from the street while helping coordinate the industrialized slaughter of humans. His private life begins to change as he becomes emotionally attached to Jasmine.

Eventually, he impregnates her, despite this act being both taboo and illegal. For Marcos, her pregnancy is not just a crime but a source of fragile hope—a suggestion that he might reclaim his humanity through fatherhood again.

This hope is tested further when his father dies. Marcos and his father had a quiet but profound bond, centered on music and birds.

His death becomes a turning point, symbolizing the erosion of the few things Marcos still cared about. The funeral, organized by Marcos’s sister, is a grotesque display of wealth and performative grief.

Guests dine on live-cut human flesh, and Marcos, appalled, replaces his father’s ashes with sand from a ruined zoo—a symbolic rejection of the inhumanity surrounding him.

Marcos continues to spiral emotionally, torn between his role in the machinery of death and his growing desire for something different. He avoids engaging with Jasmine’s pregnancy too directly, both afraid of its implications and quietly hopeful.

When she eventually goes into labor, Marcos contacts Cecilia, who briefly returns to help deliver the baby. It is a rare moment of tenderness and cooperation.

However, everything collapses when Cecilia sees Jasmine holding the child. In a state of panic or contempt, Marcos kills Jasmine, snapping her neck.

His action is immediate and brutal, yet calculated—he justifies it as necessary for the child’s survival, a reassertion of control in a chaotic world.

In this final act, Marcos completes his transformation. Though he had begun to imagine escape or redemption through love or resistance, he ultimately chooses to preserve the system.

He removes Jasmine from the equation, reduces her back to flesh, and embraces the child as his own new beginning. The implication is chilling: even those who question the system may ultimately uphold it when faced with loss, fear, or the illusion of salvation.

Tender is the Flesh offers no redemption. It reveals the quiet, devastating cost of surviving in a world that demands moral compromise.

Marcos is not a hero, nor is he a revolutionary. He is a man who allowed himself to be reshaped by a society that devalues life, and in his final choice, he reaffirms that the system has fully consumed him.

His story is not one of hope, but of submission, and the human cost of participating in normalized brutality.

Characters

Marcos Tejo

Marcos Tejo is the tormented protagonist at the heart of Tender is the Flesh, a man simultaneously numbed and undone by the dehumanized world he serves. Once emotionally tethered to a more humane reality, Marcos is now entrenched in the horrific industrial system that processes humans as meat.

His job at the Krieg Processing Plant is brutal in its mundanity—he trains workers, inspects slaughterhouses, and ensures the hygienic, efficient conversion of humans into commodities. But beneath his cold professionalism lies a man fractured by grief: the death of his infant son Leo haunts his every step, and his wife Cecilia’s emotional withdrawal has left him emotionally desolate.

Marcos’s existence is shaped by loss, guilt, and an increasingly tenuous thread of empathy that flickers despite the darkness of his surroundings.

His perspective offers a devastating lens into a world that thrives on euphemism and denial. Though he rarely acts in open defiance of the system, Marcos is clearly repulsed by it.

The language of dehumanization—the “product,” the “head,” the “special meat”—is repellent to him, even as he uses it. His discomfort intensifies when he is gifted a First Generation Pure woman, Jasmine, bred for consumption.

Her presence ignites a slow and tragic reawakening of feeling in him. He tends to her, protects her, even impregnates her, a forbidden act that briefly symbolizes rebellion and hope.

But Marcos’s final betrayal—murdering Jasmine after she gives birth—reveals the horror of his internal collapse. His actions do not free him from the system; they confirm that he has absorbed its logic so completely that love becomes indistinguishable from cruelty.

Marcos ultimately embodies the horrifying question at the heart of the novel: can anyone maintain humanity in a world built on its systematic erasure?

Jasmine

Jasmine, the First Generation Pure woman gifted to Marcos, is a central figure not for what she says—she never speaks—but for what she evokes. Raised in captivity, branded, and bred for slaughter, she is a symbol of both the system’s brutality and the last ember of Marcos’s fading humanity.

Though genetically engineered and denied any legal status as a person, Jasmine’s gradual humanization in Marcos’s eyes challenges the core premise of the society around them. Her initial portrayal is that of an object: bound, trembling, barely sentient.

Yet as Marcos begins to care for her—feeding her, bathing her, eventually letting her live free within his home—she becomes a reflection of intimacy, vulnerability, and possibility.

Her silent endurance and maternal instinct, revealed in the act of giving birth and cradling her child, pierce the numbed layers of Marcos’s psyche. But this transformation does not result in liberation.

Jasmine’s ultimate fate—being killed by Marcos just after delivering their child—is one of the most shocking betrayals in the novel. Her death serves as a devastating reminder that love, care, and even pregnancy are not enough to shield anyone from institutionalized violence when that violence has become normalized.

Jasmine is both a mirror to Marcos’s conscience and a sacrificial figure, one who embodies the tragedy of a world in which personhood is contingent on power, and tenderness is a temporary illusion.

Cecilia

Cecilia, Marcos’s estranged wife, is largely an absent figure throughout Tender is the Flesh, but her absence is deeply felt. She embodies the psychological shattering that grief can inflict.

Following the death of their son, Leo, Cecilia retreats from their shared life, unable—or unwilling—to return to the home that once held their hope for a family. Marcos often thinks of her with a mix of longing and sorrow, acknowledging how the emotional chasm between them was carved not just by loss, but by their failed attempts at parenthood.

Fertility treatments, miscarriages, and emotional isolation have drained them both, but Cecilia’s retreat signals a refusal to function within a world that has broken her.

Her reappearance during Jasmine’s labor is a poignant and ironic twist. It is she, the grieving mother, who helps deliver the child conceived in moral ambiguity.

Though the scene holds potential for redemption, it collapses under the weight of Marcos’s subsequent betrayal. Cecilia’s role in this moment underscores the emotional contradictions at play: she is a caretaker in a world that has nothing left to nurture.

Her exit after the birth parallels the fragility of human connection in the face of insurmountable trauma and suggests that she, like Marcos, is irreparably damaged, though her refusal to participate in the system may be a quieter, more principled resistance.

Señor Urami

Señor Urami is a chilling embodiment of capitalist amorality, a man who runs a tannery converting human skin into high-end leather products. He views the human “product” entirely through a commercial lens, obsessed with quality, efficiency, and market expansion.

In his eyes, people are no longer people—they are raw materials to be harvested and processed. Urami’s enthusiasm for innovation—better tanning techniques, higher-grade skins—exemplifies how enterprise adapts and thrives even in the face of moral collapse.

His role in the novel is to showcase how deeply and enthusiastically industry has embraced cannibalism not just as necessity, but as opportunity.

His conversations with Marcos are laced with unintentional horror, precisely because of their mundane nature. Business talk about skin elasticity or preservation techniques takes on a grotesque undertone in the context of human leather.

Urami does not present as a sadist or overt villain; his demeanor is genial, even cultured. This contrast heightens the dystopian tragedy of the novel: evil here is not monstrous—it is normalized, efficient, and polite.

Urami’s character is a reflection of the banality of evil, where ethical considerations are displaced by supply chains and consumer demand.

Urlet

Urlet, the owner of a human hunting reserve, represents the ultimate convergence of spectacle, brutality, and elite indulgence. His business model is one of recreational horror: offering clients the thrill of hunting humans for sport.

The “prey” often includes social outcasts or celebrities seeking redemption from scandal, who volunteer in exchange for financial compensation to their families or to clear debts. Urlet’s operation reflects a society not just comfortable with violence but entertained by it.

He is both impresario and predator, orchestrating death as performance.

In Marcos’s interactions with Urlet, a grimly voyeuristic tone prevails. The reserve’s trophies—mounted human heads—serve as grotesque souvenirs of societal depravity.

Urlet’s business is a natural extension of the world’s logic, where humans are property and consumption extends beyond flesh to experience. His character reinforces the idea that once ethical lines are crossed for survival, they will continue to erode until pleasure itself is derived from cruelty.

Urlet is a purveyor of elite barbarism, exploiting the collapse of ethics for amusement and profit.

Guerrero Iraola

Guerrero Iraola is perhaps one of the most grotesque figures in the novel, a supplier of “special meat” who embodies both wealth and depravity. He relishes in recounting the rape and consumption of a young girl, presenting his crimes not as horrors but as luxuries.

Iraola is fully aware of the power his position affords him and uses it without restraint. At his dinner party, he serves up parts of a popular musician and celebrity victims, delighting in the shocked reactions and thinly veiled envy of his guests.

He symbolizes a society where depravity has become a status symbol. His character exposes the toxic intersection of wealth, power, and legalized violence.

More than just complicit, Iraola is celebratory in his abuse of the system. He is the manifestation of privilege weaponized, where human suffering is a delicacy and cruelty a form of entertainment.

Marcos’s revulsion in Iraola’s presence highlights the faint boundary between those who internalize the system with shame and those who exploit it without remorse. Iraola, in all his grotesqueness, stands as a warning of what power looks like when morality is stripped away completely.

Themes

Dehumanization and Bureaucratic Violence

Language and routine strip away identity, transforming people into “product” and “special meat. ” This is not just a matter of semantic convenience—it is a foundational pillar of the dystopian economy.

In Tender is the Flesh, dehumanization is enacted with clinical precision, built into every level of the system. By systematically reducing humans to commodities, the industry fosters a cognitive dissonance that enables violence without remorse.

Employees like Marcos participate in atrocities while rationalizing their work as merely fulfilling a logistical necessity. Workers in slaughterhouses refer to people in terms typically reserved for livestock—“heads,” “balanced feed,” “vaccinated udders”—demonstrating how language becomes a tool of psychological distance.

This distance allows workers to slaughter, dissect, and consume humans without confronting the ethical implications. The bureaucracy functions as a moral vacuum, insulating its participants from the consequences of their actions.

In the tannery, people are described as leather-producing assets; at game reserves, they become prey; in breeding centers, they are reduced to reproductive machinery. Everything is logged, measured, and processed with detached efficiency.

Even grief and memorial are commodified, as seen in Marcos’s sister’s grotesque display of power during their father’s wake. The system thrives not just because of violence but because that violence is filtered through institutions that normalize, legalize, and aestheticize it.

Dehumanization becomes not an aberration, but a bureaucratic function of the state.

Complicity and Moral Erosion

What makes Tender is the Flesh particularly haunting is its portrayal of passive complicity. Marcos does not actively endorse the system—he loathes much of what he sees—but he remains deeply enmeshed in it.

His grief over his son’s death and his estrangement from his wife do not radicalize him; rather, they leave him emotionally blunted and unable to rebel. The psychological toll of his work seeps into every corner of his existence, yet he continues performing his role as plant administrator with unflinching competence.

He blacklists applicants, trains workers to kill efficiently, and oversees the conversion of human beings into processed goods. His few acts of resistance—naming Jasmine, showing her kindness, rescuing puppies—are ultimately insufficient.

When he kills Jasmine after she gives birth, the moral line he pretended to preserve collapses. Marcos embodies the gradual erosion of ethics under sustained institutional pressure.

He recognizes the horror of the world but lacks the will or power to reject it meaningfully. In doing so, he illustrates how ordinary individuals, given the right conditioning and incentives, can become instruments of unimaginable cruelty.

The story does not offer Marcos redemption or even transformation—it offers a portrait of someone broken down incrementally, until he becomes indistinguishable from the system he despises.

Grief, Loss, and Psychological Disintegration

Marcos’s psychological unraveling is inseparable from his grief. The death of his infant son Leo is not just a personal tragedy—it becomes the silent lens through which all horror is refracted.

His interactions with the world are drained of vitality, as though mourning has sapped his capacity for moral judgment. His wife’s departure leaves a hollow in his domestic life, and his father’s slow decline into dementia erases any remnants of familial continuity.

This cumulative loss underpins Marcos’s passivity. The few moments of tenderness he expresses—burning the cot, bathing Jasmine, petting the rescued puppies—are not acts of rebellion, but brief flickers of a humanity that can no longer fully resurface.

Even his bond with Jasmine is filtered through his trauma; she becomes a surrogate for everything he has lost. Her pregnancy offers a glimmer of future, yet that future is fatally compromised the moment he murders her.

Marcos’s grief is not cathartic—it is corrosive. It warps his perception, isolates him emotionally, and slowly renders him incapable of discerning right from wrong.

Rather than healing, grief calcifies within him, driving him deeper into a psychological landscape where survival eclipses compassion and morality becomes expendable.

Power, Class, and Systemic Oppression

Cannibalism in Tender is the Flesh is not merely a response to ecological catastrophe—it is a mechanism of authoritarian control. The virus that made animal meat inedible becomes a convenient pretext for a global reordering of power.

The poor, immigrants, and the socially vulnerable are systematically reduced to food stock, while the wealthy exploit this new order to indulge in grotesque displays of dominance. Men like Urlet hunt humans for sport; disgraced celebrities offer themselves as prey to pay off debts; the Church of the Immolation turns sacrifice into spiritual spectacle.

These are not anomalies—they are features of a stratified society that commodifies bodies according to class. Marcos, though occupying a high-status role, is not immune from the social violence that undergirds the system.

His own suffering is partly the result of this structure: a failing healthcare system, economic collapse, and unrelenting societal pressure. Yet, rather than challenge the hierarchy, Marcos upholds it.

His personal authority within the plant and his proximity to powerful figures give him the illusion of autonomy, but he remains a cog in a much larger machine. The novel emphasizes how systemic oppression persists not just through force but through complicity, legal precedent, and institutional inertia.

Power becomes self-sustaining, justified through the logic of efficiency, necessity, and economic stability.

Language as a Tool of Ideological Control

Words are weaponized in Tender is the Flesh to sever meaning from morality. The linguistic shift from “human” to “product” is not simply a euphemism—it is a calculated redefinition of reality.

By renaming people as consumables, the system eliminates the ethical friction that would otherwise arise. Language shapes perception, and perception governs action.

Workers speak in industry jargon that makes slaughter feel like hygiene. Media narratives, government mandates, and religious dogma reinforce this rebranding, turning cannibalism into patriotism, sacrifice, or progress.

Even acts of atrocity are couched in sterile, professional terms—“stunning,” “processing,” “harvesting. ” These words anesthetize violence, allowing people to participate in or observe horrors without reacting.

Marcos, too, relies on this linguistic filter to navigate his daily life. His mental stability depends on not calling things what they are.

When he begins to see Jasmine as a person, the structure begins to falter—yet the language holds. Even in the final moments, when he murders her, he does not call it killing.

The perversion of language ensures the persistence of ideology. Truth becomes elastic, molded to serve the interests of power, and dissent becomes almost impossible when words themselves have been redefined to exclude it.

The Illusion of Redemption

Marcos’s relationship with Jasmine appears, for a moment, to offer the possibility of transformation. He names her, shelters her, and eventually fathers a child with her—acts that suggest a movement toward reclamation of lost humanity.

But this redemption is superficial. It is not grounded in ethical reckoning but in emotional substitution.

Jasmine is not freed because Marcos sees her as equal; she is spared because she represents something he cannot otherwise access: companionship, fatherhood, emotional continuity. The moment she fulfills her role as mother, however, her value in his eyes shifts.

Her agency, even in something as basic as maternal love, becomes threatening. By killing her, Marcos enforces the logic of the system he pretends to resent.

Redemption, then, becomes another illusion in a society where even kindness is contaminated by power dynamics. The story’s final image—Marcos holding the infant—suggests a man clinging to the appearance of rebirth while covered in the residue of his own violence.

There is no catharsis, only continuation. The cycle resets, the system endures, and redemption is reduced to a gesture—hollow, performative, and ultimately tragic.