The Age of Magical Overthinking Summary, Analysis and Themes

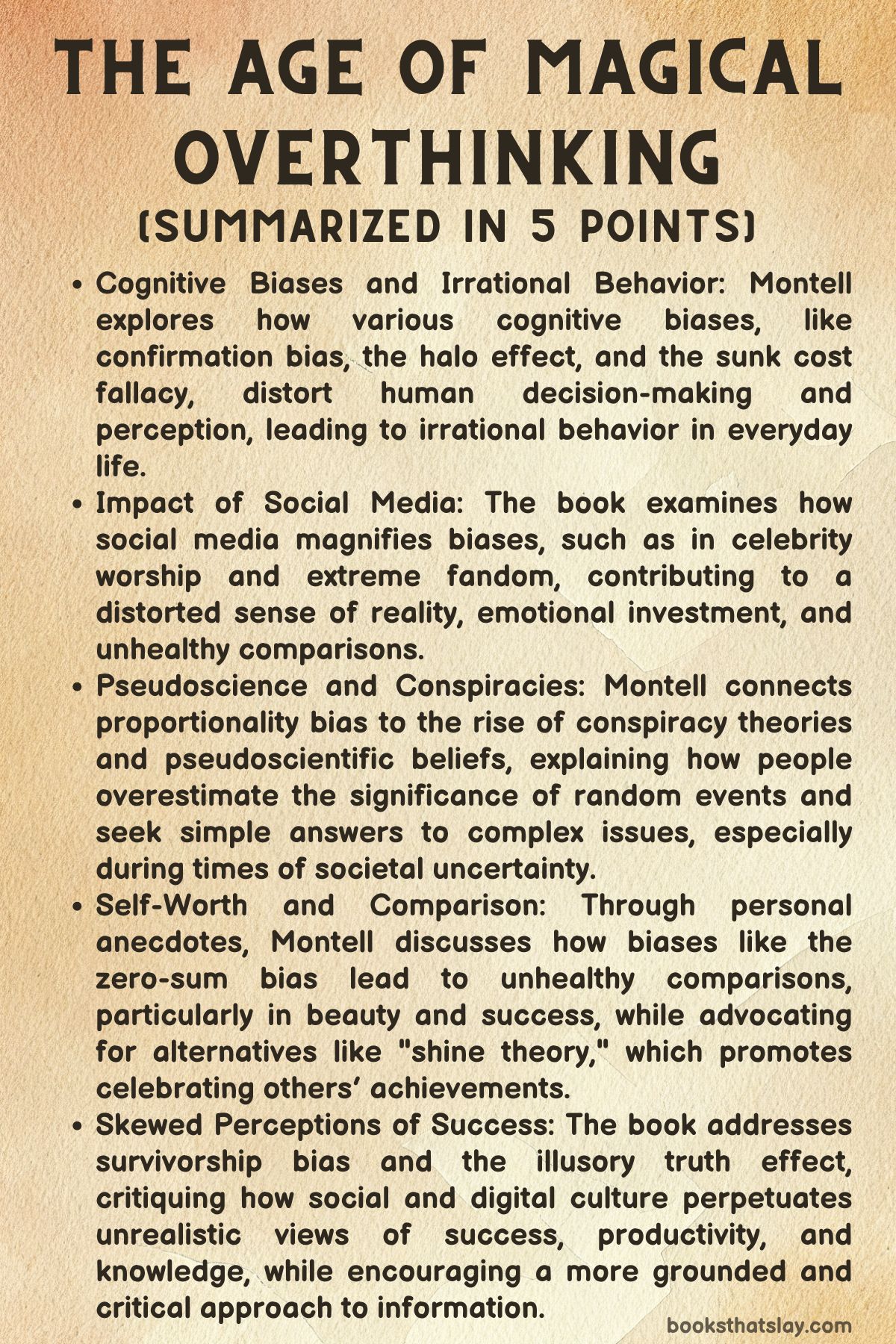

The Age of Magical Overthinking by Amanda Montell, published in 2023, delves into how cognitive biases distort modern human thinking. Known for her previous work Cultish, Montell brings her expertise in sociolinguistics to this book, blending personal stories with scientific insights to explore why people often make irrational decisions.

Through relatable anecdotes and deep dives into biases like confirmation bias and the sunk cost fallacy, Montell uncovers how we overestimate patterns, cling to flawed beliefs, and are often guided by emotions rather than logic in a world saturated with information.

Summary

In The Age of Magical Overthinking, Amanda Montell investigates the powerful role cognitive biases play in shaping irrational behavior today.

The book opens with Montell’s reflection on her own emotional struggles, including staying in a dysfunctional relationship, influenced by cognitive traps like the halo effect and proportionality bias. These biases, she argues, distort our understanding of reality, causing us to overestimate connections between events and misinterpret the world around us.

In the first chapter, Montell turns her attention to celebrity culture and extreme fan behavior, diving into the psychology behind the phenomenon of “stanning.” She ties this intense admiration to the halo effect, where fans glorify public figures and project qualities onto them that might not exist.

Social media, Montell contends, amplifies this effect, fostering environments where fans become irrationally protective and emotionally attached to their idols.

Next, Montell examines the proportionality bias, which explains why people often inflate the significance of random events and fall into conspiracy thinking. Drawing on examples like influencers promoting pseudoscientific beliefs, Montell explains how social media plays a role in magnifying these irrational narratives.

She connects this trend to a broader societal mistrust in authority and the tendency to seek simple explanations for complex issues, particularly in a post-pandemic world.

Montell also tackles the sunk cost fallacy in a more personal chapter, recounting her seven-year relationship with a man she calls “Mr. Backpack.” Despite realizing the relationship wasn’t healthy, Montell remained committed, rationalizing that the more effort she invested, the more likely it would improve.

This fallacy, she argues, traps people in unproductive cycles in relationships, work, and even financial investments, driven by cultural pressures to persevere at all costs.

A subsequent chapter dissects how digital culture exacerbates self-perception problems through the zero-sum bias—the belief that another’s success means your failure. Montell discusses her own experiences in the beauty industry, where constant comparison to curated images of perfection drove unhealthy competition.

Social media, Montell notes, fuels this mindset, contributing to self-esteem issues.

She advocates for “shine theory,” which encourages celebrating others’ achievements instead of seeing them as personal losses.

Survivorship bias is another cognitive trap Montell unpacks, explaining how it distorts our understanding of success. By focusing on success stories—like a friend who overcame cancer—we tend to overlook those who don’t make it, creating unrealistic expectations.

Montell critiques how social media reinforces these skewed narratives, leading to an overly optimistic view of success while ignoring the struggles of the less fortunate.

Further, she explores the recency illusion, the tendency to view current events as novel or unique simply because they’re fresh in our minds.

Montell criticizes how news cycles and social media contribute to this distortion, overwhelming our capacity for rational thought.

Later, she discusses overconfidence bias, using the infamous story of a failed bank robber to illustrate how people often overestimate their abilities despite limited knowledge.

She then delves into the illusory truth effect, describing how repetition reinforces misinformation, which becomes more believable over time. Finally, Montell critiques the nostalgia for a seemingly simpler past, coining a new term, “tempusur,” as an antidote—an appreciation for the fleeting present.

The book concludes with a discussion of the IKEA effect, highlighting how the effort we invest in something increases its perceived value, leaving readers with an optimistic reminder of human adaptability in a rapidly changing world.

Analysis and Themes

The Influence of Cognitive Biases on Emotional and Behavioral Irrationality

In The Age of Magical Overthinking, Amanda Montell introduces the complex and pervasive role cognitive biases play in shaping modern human irrationality. By dissecting biases such as the halo effect, proportionality bias, and the sunk cost fallacy, Montell illustrates how these cognitive distortions can lead to irrational emotional and behavioral patterns.

For example, the halo effect, which leads people to overestimate positive attributes in others, is used to explain the extreme emotional investment that fans place in celebrities. Montell further highlights how these distorted perceptions are exacerbated by the digital landscape, where constant exposure to curated images and ideas strengthens irrational attachments.

Montell’s exploration of proportionality bias underscores how humans tend to inflate the significance of certain events, particularly in the context of conspiracy theories. She delves into the psychological need to make sense of the world through simplified, exaggerated interpretations, especially when faced with uncertainty or fear.

This tendency, she argues, is deeply entrenched in modern culture, where misinformation thrives, and pseudoscience, like The Manifestation Doctor’s ideologies, takes root among populations increasingly mistrustful of traditional institutions. Montell also critiques how these biases intertwine with societal pressures, emphasizing how confirmation bias reinforces skewed worldviews by filtering out disconfirming evidence.

This interplay between biases and societal influences results in people clinging to beliefs that rational analysis would otherwise dismantle.

The Digital Amplification of Irrational Self-Perception

Montell’s discussion of the zero-sum bias illuminates the toxic impact that digital culture has on self-perception, particularly in spaces where success and self-worth are perceived as finite resources. Social media, with its endless parade of curated success stories and images of beauty, becomes a battleground for self-worth, where individuals continually compare themselves to others in an unhealthy competition.

Montell reflects on her personal experience within the beauty industry, drawing attention to the emotional toll that perfectionism and comparison take in this context. This exploration of self-perception is further complicated by Montell’s introduction of survivorship bias, where attention is disproportionately focused on individuals who succeed, ignoring those who fail.

The result is a skewed narrative about success, leading to unrealistic expectations and the erroneous belief that hard work guarantees a positive outcome. Montell’s critique here ties into a broader discussion of how social media perpetuates distorted success stories, creating a false sense of what it means to achieve and thus deepening individuals’ dissatisfaction with their own lives.

Overconfidence and the Dangers of Misinformation

Montell’s examination of overconfidence bias and its ties to the Dunning-Kruger effect presents a detailed critique of the ways in which ignorance is often paired with inflated self-perception. The infamous case of McArthur Wheeler, who attempted to rob a bank believing lemon juice would render him invisible, serves as a compelling anecdote of how misinformation and overconfidence can lead to disastrous outcomes.

Montell traces this cognitive fallacy to a larger cultural phenomenon, where American society tends to celebrate overconfidence—through mantras like “fake it ’til you make it”—without recognizing the potential dangers of such inflated beliefs in one’s own abilities. This problem is compounded by the illusory truth effect, another cognitive bias Montell examines in detail.

This effect refers to the human tendency to believe in false information simply because it has been repeated often enough. Montell shares an example from her own life, where she believed a historical myth about wedding bouquets until she was corrected by an expert.

Her discussion critiques how repetition reinforces misinformation, whether in personal beliefs or more widespread societal narratives, such as false medical claims or harmful stereotypes. In today’s media landscape, where repetition is the backbone of misinformation campaigns, Montell’s analysis is particularly salient, showing how even seemingly harmless myths can perpetuate larger issues of irrationality and cognitive distortion.

The Psychological Pull of Nostalgia and the Weaponization of Declinism

Montell’s discussion of anemoia—a term that describes nostalgia for a time one has never experienced—provides a profound commentary on the ways cognitive biases warp our perception of both the past and the present. She links this bias to declinism, the belief that society is in a state of decline, despite evidence of progress in areas like poverty reduction and literacy improvement.

Montell argues that the longing for an idealized past, often exacerbated by present bias and the fading affect bias, is not only irrational but also dangerous, as it can lead to regressive thinking and even apocalyptic fears. Montell critiques how political figures and marketers often exploit this nostalgia for personal gain, stoking fear and dissatisfaction in modern society.

Her exploration goes deeper into how these biases, particularly present bias, obscure the genuine improvements in the quality of life that many people experience, leading them to focus only on short-term crises. By pointing out how media and political forces weaponize this sense of societal decline, Montell argues that declinism becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, discouraging critical thinking and leading to increased irrationality.

Montell calls for a more nuanced understanding of historical progress, encouraging readers to engage with the present moment with a sense of appreciation, which she terms “tempusur.” This concept promotes the idea of mindfulness in the face of modern chaos, suggesting that grounding oneself in the present can counteract the despair often fueled by cognitive biases like declinism and anemoia.

The Intersection of Productivity, Capitalism, and Cognitive Bias

In her final chapter, Montell’s analysis of the IKEA effect—the tendency to overvalue something that one has created—serves as an insightful commentary on the relationship between personal productivity, societal pressures, and cognitive biases. The IKEA effect taps into the human desire for agency and accomplishment, particularly in a world where capitalist ideals push individuals to constantly strive for more.

Montell draws on her own experiences flipping furniture with her friend during the pandemic, highlighting how working with her hands provided a sense of fulfillment that other modern, technology-driven activities could not. However, Montell critiques how this bias also plays into the capitalist narrative, where effort and productivity are often conflated with self-worth.

She notes the dangerous overlap between the IKEA effect and the sunk cost fallacy, where individuals become trapped in harmful situations simply because they have invested so much time or energy into them. While Montell acknowledges the emotional satisfaction that productivity can provide, she warns against overvaluing it in ways that distort one’s sense of purpose.

Her analysis concludes by reflecting on the role of adaptability in the face of rapid technological change, arguing that while machines may become more advanced, human resilience remains a crucial constant. Montell’s ultimate message is one of cautious optimism, urging readers to embrace their own adaptability while remaining aware of the cognitive biases that shape their perceptions and decisions.