The Answer Is No Summary, Characters and Themes

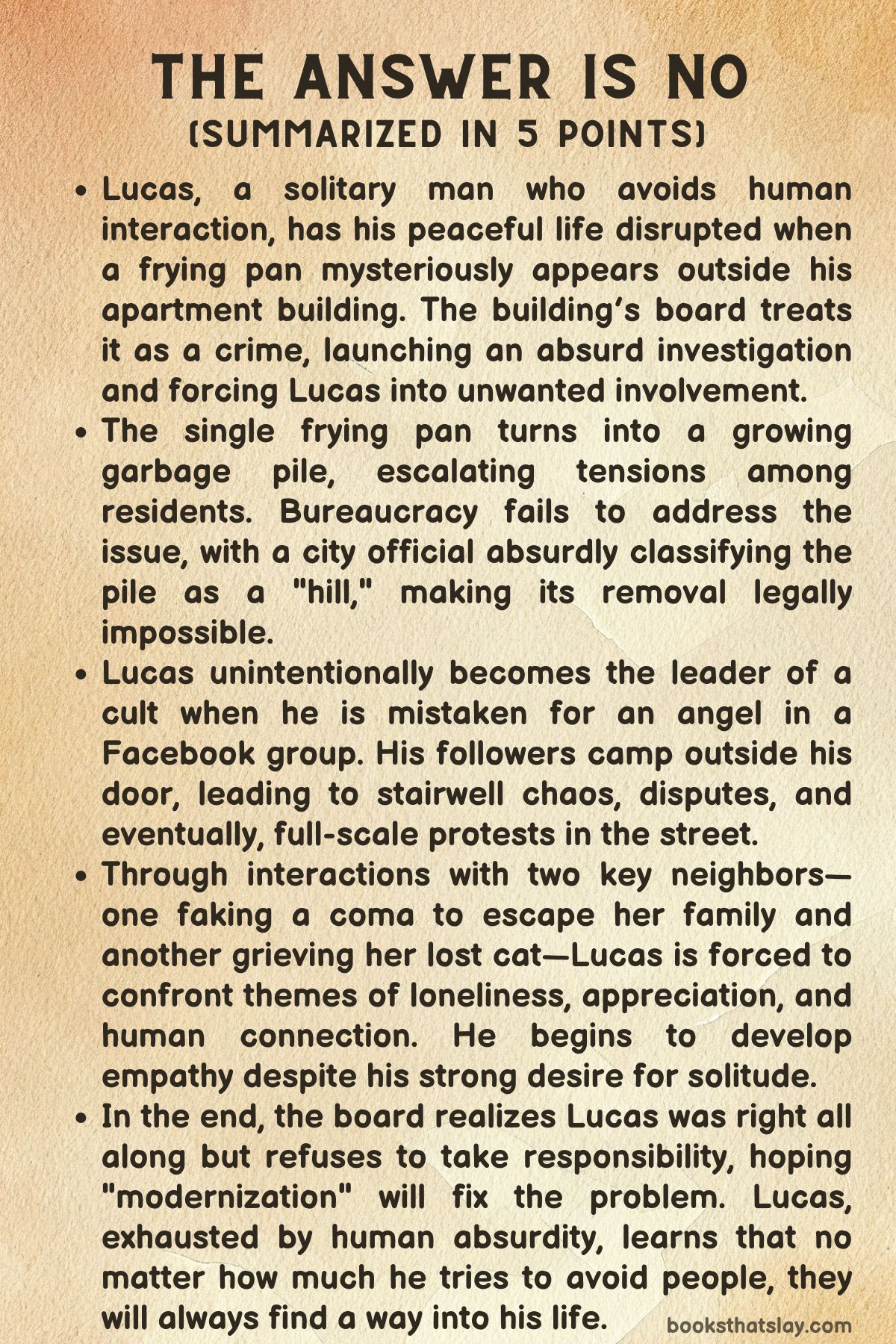

The Answer Is No by Fredrik Backman is a short story that explores the chaotic intersection between isolation, community, and the absurdity of modern civic life. Known for his ability to inject humor into the ordinary and infuse emotion into everyday encounters, Backman presents Lucas, a man who thrives in solitude until he is inadvertently thrust into a communal drama sparked by a discarded frying pan.

This story uses wit and satirical observations to examine how minor disruptions can unravel rigidly controlled lives and how connection can sometimes come in the most disorderly and unexpected ways. The result is a narrative that both critiques and celebrates the messy nature of being human.

Summary

Lucas lives alone and prefers it that way. His days are designed around complete isolation, filled with personal routines that no one interferes with.

His apartment is spotless, his work as a tech professional is remote and efficient, and he avoids human interaction at every possible turn. For Lucas, happiness is control—order without interruption, peace without conversation, days without emotional labor.

This delicate balance is broken by something seemingly trivial: a frying pan left outside the recycling room in his apartment building. While such a detail may be irrelevant to most, to Lucas, it is a violation of the unspoken agreement he has with the world to be left alone.

Unfortunately for him, this frying pan draws the attention of the building’s board—a bizarre trio acting like a multi-headed bureaucratic machine—who descend upon his quiet sanctuary not to fix the problem but to assign responsibility. Through a twisted logic only bureaucracy could defend, Lucas is appointed president of the “Pile Committee,” a role created solely to deal with the frying pan situation.

As Lucas attempts to avoid further involvement, the problem escalates. Neighbors begin to discard more items near the pan—an old television, rugs, candlesticks.

The area outside the building turns into a cluttered eyesore. Lucas tries to clean it up, but his efforts are hindered by rules, stubborn residents, and the city’s absurd classifications.

Instead of acknowledging the growing mound as garbage, local officials deem it a “hill,” which places it outside standard waste management procedures. Lucas is stuck.

The more he tries to assert control or reason, the more convoluted the situation becomes.

The pile outside becomes more than trash—it becomes a catalyst for social disarray and bizarre community theater. The local Facebook group seizes on the issue, spinning the growing heap into viral drama.

One faction frames the pile as an environmental statement, another as an artistic protest. Things take a surreal turn when a cult-like group mistakes Lucas for a prophetic figure based on a manipulated photo and a misunderstood post.

They descend upon the pile, treating it as a sacred monument and Lucas as a celestial messenger.

Amid this growing madness, Lucas is reluctantly pulled into deeper human connections. Two women become recurring figures in his life: one in a purple dress and one in a green shirt.

The woman in the purple dress is eccentric, talkative, and invasive. She steals his Wi-Fi and refuses to let his silence end their conversations.

The woman in the green shirt is more enigmatic—she’s pretending to be in a coma, staying away from her family to escape the exhaustion of daily life. Through each of these women, Lucas is confronted with what he has shut out: grief, frustration, longing, the need to be seen.

These interactions begin to soften Lucas. Though he remains resistant to change on the surface, something inside him starts to shift.

He notices the emotional weight others carry, the cracks in their performances, the loneliness behind their outbursts. And as the pile continues to grow, so does Lucas’s awareness that disconnection doesn’t equate to peace—it just delays the inevitability of emotional messiness.

Lucas decides to manipulate the madness. Using satire and the very social media networks that propelled the chaos, he begins posting messages in conflicting online groups.

In one, he claims the pile is sacred; in another, he calls it a disgrace. The posts inspire both worship and fury, and people begin removing the trash—not out of civic duty, but to either protect or destroy what they believe the pile represents.

In an ironic twist, his reverse psychology succeeds where logical appeals failed. The junk vanishes, piece by piece.

But the story’s heart lies not in the cleanup, but in the emotional transformation that occurs around it. The woman in the green shirt decides to return to her family, moved by the strange clarity her escapade has given her.

The woman in the purple dress, still mourning a lost cat, finds a new kitten beneath the last remaining item in the pile. Each discarded object seems to carry a metaphorical weight, and as the community removes the mess, they also unburden themselves from their inner clutter.

Lucas, too, changes. While he doesn’t become a fully engaged member of society, he stops actively resisting connection.

He shares moments of empathy and kindness, recognizing that isolation, though comfortable, can be sterile. In an ironic conclusion, Lucas fakes a coma himself—a symbolic gesture of withdrawal not as escape but as quiet resistance against the absurd demands placed on him.

He is not running away, but rather creating space for himself on his own terms, now with a fuller understanding of the chaos and beauty of human interaction.

The Answer Is No ends not with triumphant transformation, but with the quiet compromise of someone who has learned that absolute solitude is not sustainable, and that even in absurdity, there is meaning. The pile was never just trash.

It was the physical manifestation of ignored burdens, quiet griefs, and communal confusion. And by facing it—even reluctantly—Lucas, and those around him, find a way to reconnect with themselves and each other.

Analysis of the Characters

Lucas

Lucas, the central figure in The Answer Is No, is a man deeply entrenched in solitude by choice. His world is meticulously crafted to ensure minimal interaction with others—a controlled, orderly life defined by predictability and privacy.

Lucas embodies the modern-day recluse, someone who has opted out of society not out of misanthropy, but out of a profound need for emotional self-preservation. His apartment is pristine, his routine unbroken, and his interactions with others almost nonexistent.

This isolation initially reads as self-sufficiency, but as the story unfolds, it becomes clear that Lucas’s detachment is also a defense mechanism against the chaos and vulnerability of human connection.

Lucas’s descent into reluctant civic engagement begins with something as innocuous as a frying pan, which becomes the symbolic intrusion that unravels his perfectly composed life. Despite his resistance, he is thrust into the bureaucratic absurdity of committee politics and neighborhood disputes, revealing his latent frustration with institutional inefficiency and social obligations.

What makes Lucas particularly compelling is how his transformation is triggered not by a dramatic event but by the slow, inevitable friction between his private world and the larger, messier human collective. He does not seek leadership or responsibility, yet the pile of junk outside the building—and the emotional baggage it represents—pulls him into an unintended role of mediator and reluctant savior.

Through his interactions with his neighbors, especially the women in the green shirt and the purple dress, Lucas begins to thaw. His empathy, once hidden beneath layers of sarcasm and detachment, emerges in subtle but meaningful ways.

These women confront him with their own brokenness—grief, exhaustion, loneliness—and in doing so, mirror his own buried needs. His final act of pretending to fall into a coma mirrors his initial strategy of withdrawal, but now it comes with nuance: not as a rejection of connection, but as a temporary respite to recover from its demands.

Lucas becomes a symbol of reluctant growth—a man who doesn’t seek transformation, yet is undeniably changed by the absurdities and intimacies of communal life.

The Woman in the Green Shirt

The woman in the green shirt represents the quiet desperation that often lies beneath the surface of seemingly ordinary lives. She is a character who has reached a point of emotional and psychological exhaustion, choosing to feign a coma just to escape the pressures of family life and societal expectations.

Her extreme act is not played purely for humor—it’s a powerful commentary on burnout and the invisible labor so many people, particularly women, carry. Her character arc offers a sharp yet tender critique of how society normalizes the erasure of personal needs in favor of fulfilling roles as caregivers, partners, or parents.

Her interaction with Lucas becomes a turning point for both of them. Unlike the more intrusive woman in the purple dress, the woman in the green shirt engages Lucas on a level that is deeply vulnerable and sincere.

She does not demand his attention or invade his space, but rather offers a moment of honesty that breaks through his guarded shell. Her presence forces Lucas to recognize not only the burdens others carry but also his capacity for compassion.

By choosing to return to her family after her staged retreat, she illustrates the power of brief detachment as a form of healing. She is not portrayed as a martyr but as someone who dares to reclaim her agency, however unorthodox her method.

Her decision to reconnect with her family is less a resignation and more a re-entry into life on her own terms, suggesting that healing is possible when one is finally seen and heard.

The Woman in the Purple Dress

The woman in the purple dress is the comic foil to Lucas’s guarded stoicism. Bold, eccentric, and unapologetically present, she invades Lucas’s controlled universe with cheerful chaos.

Her character is the embodiment of social energy—unfiltered, excessive, and yet necessary. She steals his Wi-Fi, inserts herself into conversations, and refuses to be ignored.

Initially, she seems like a mere irritant, someone whose purpose is to challenge Lucas’s boundaries for comedic effect. But as the story unfolds, it becomes evident that her intrusive behavior masks her own emotional vulnerability.

Her grief over the loss of her cat introduces a layer of poignancy that reframes her actions. What first seemed like overbearing nosiness is now understood as a desperate attempt to connect, to matter, to be seen.

Her reaction to finding a new kitten beneath the last piece of trash is a moment of quiet redemption—a discovery of hope amidst detritus. It marks a gentle turning point for her character, reaffirming her belief in life’s small, magical recoveries.

Through her, the story illustrates that the loudest people are often the loneliest, and that human connection can be found in the most absurd places. Her relationship with Lucas evolves into a cautious camaraderie, with both parties learning to navigate the messy terrain of emotional exposure.

She teaches Lucas, in her own chaotic way, that disruption can also be an invitation to feel.

The Apartment Board (The Three-Headed Bureaucratic Hydra)

The apartment board in The Answer Is No is not a character in the traditional sense, but rather a satirical embodiment of institutional bureaucracy. Described as a three-headed hydra, it represents the maddening inefficiency and faceless authority that govern communal life.

This collective entity is more concerned with following rules, filling out forms, and adhering to absurd municipal categorizations than with actually solving problems. Their inability to see the pile of junk as a “pile” because it must legally be classified as a “hill” captures the Kafkaesque absurdity that pervades the story.

They are a perfect foil to Lucas, whose instinct is to clean and fix rather than delegate and defer.

The board’s role is crucial in escalating the central conflict. Their rigidity and detachment from common sense propel Lucas into an unwanted leadership role, exposing the emptiness at the heart of civic procedure.

They illustrate how bureaucracy, while intended to bring order, often results in the opposite: confusion, frustration, and inertia. The hydra’s many heads can be read as a metaphor for how authority becomes fragmented and absurd when too many people are involved without shared vision or empathy.

In this sense, the apartment board functions both as a comedic element and a critique of how modern societies manage collective spaces—by valuing compliance over connection, and regulation over responsibility.

The Cult Members and Protesters

The cult members and protesters who appear in the story are extreme yet accurate reflections of how digital culture magnifies absurdity. Triggered by a viral Facebook post, these individuals descend upon the junk pile, misinterpreting Lucas as a divine figure or a symbol of their ideological cause.

These characters, while not deeply developed, are integral to the story’s satire. They highlight how misinformation and longing for belonging can lead to surreal outcomes—people rallying around literal garbage in search of meaning.

Their presence emphasizes the central theme that collective nonsense can sometimes achieve what reasoned debate cannot.

Ironically, it is through their chaotic engagement that the pile is finally dismantled. Whether acting out of worship or opposition, these strangers unknowingly collaborate to resolve the very conflict they helped escalate.

They function as both the problem and the solution, a paradox that reflects the unpredictable power of collective behavior in the digital age. In them, The Answer Is No finds a strange optimism: that human beings, even when misguided, are capable of inadvertently healing one another through shared participation, however irrational the impulse.

Themes

Isolation and the Comfort of Control

Lucas’s life is defined by solitude, built on a foundation of routines and predictability. His meticulous avoidance of human contact, his home-based job, and his obsession with order reflect a profound fear of unpredictability that other people inevitably introduce.

He is not lonely in the traditional sense—he is at peace in his isolation, having constructed a reality where everything from his meals to his entertainment is under his precise control. Yet this control is a fragile illusion, and the moment the frying pan appears, it begins to unravel.

The frying pan’s presence is not just physical clutter; it is symbolic of intrusion. It challenges his self-contained world and forces him into interaction, thereby triggering a slow dismantling of his rigid boundaries.

The narrative illustrates that isolation can masquerade as comfort but is often a form of self-protection rooted in fear, trauma, or exhaustion. While Lucas initially resists engagement, the chaos that follows paradoxically nudges him toward re-evaluating the limits of his solitude.

His journey exposes the unsustainable nature of extreme isolation in a world that thrives on connection, however messy or absurd. In the end, his final gesture of pretending to be in a coma isn’t a return to his old life but rather a nuanced compromise—a retreat that acknowledges the need for boundaries after exposure, rather than total detachment.

Bureaucracy and Absurdity

The book takes a sharply comic stance on bureaucracy, illustrating its inefficiency and surreal logic through the escalation of the trash pile. The apartment board, represented as a “three-headed hydra,” is a personification of bureaucratic absurdity—simultaneously oppressive, ineffective, and blind to human nuance.

The refusal to remove the pile because it has been reclassified as a “hill” exposes the farcical nature of administrative rule-following, where logic and utility are sacrificed for procedural correctness. Lucas’s reluctant role as the head of the “Pile Committee” underscores how systems often thrust responsibility onto those least willing to participate, while those invested in rules often lack the courage or flexibility to act meaningfully.

The narrative critiques how bureaucracy distances people from common sense and empathy, trapping them in cycles of blame, paperwork, and inaction. The transformation of the pile into a quasi-political battlefield—complete with cults, protests, and viral online movements—extends the absurdity from institutions to society at large.

This reflects how systems designed to maintain order often magnify disorder when they prioritize symbolism over substance. The satirical tone isn’t merely for laughs; it’s a reflection on the frustration of dealing with systems that are too rigid to accommodate human imperfection or emotion.

Ultimately, the bureaucratic paralysis in the story serves as a backdrop to Lucas’s personal awakening and highlights how absurdity often stems not from individuals, but from the systems meant to serve them.

Community, Chaos, and Connection

Lucas’s gradual, reluctant integration into his community is marked by a collision between order and chaos. The neighbors, initially seen as nuisances, become agents of transformation.

The woman in the purple dress disrupts his peace with her boldness and unapologetic presence, while the woman in the green shirt embodies quiet desperation beneath a façade of domestic normalcy. Both women, through their vulnerability and persistence, draw Lucas into moments of genuine emotional engagement.

The chaos that ensues—the trash pile, social media cults, protests—is the result of collective action gone awry, but it also provides a strange sort of bonding. The story suggests that community doesn’t form out of perfection or alignment; it emerges from shared absurdities, frustrations, and accidental alliances.

People rally around the pile not because they care about sanitation, but because it becomes a canvas for their anxieties, beliefs, and needs to be seen. Lucas’s manipulative use of satire to unite opposing groups, though cynical in design, results in a moment of collective catharsis and cleanup.

In this bizarre triumph, the book shows that even flawed, disorganized, and irrational human activity has the potential to create meaning and connection. The messy, unpredictable human web that Lucas once avoided becomes a source of revelation and, ultimately, emotional healing.

His shift from observer to participant is not heroic but deeply human—a recognition that connection, however strange its path, is a fundamental part of life.

Emotional Baggage and the Need for Release

The trash pile becomes more than an external nuisance; it acts as a metaphorical dumping ground for the characters’ internal clutter. Each discarded object embodies a piece of emotional residue—things people cannot confront directly but must symbolically expel.

The pile’s physical expansion mirrors the swelling weight of unaddressed grief, burnout, guilt, and dissatisfaction. For the woman in the green shirt, pretending to be in a coma is her own version of the pile—a desperate method to step outside of life’s relentless demands.

For the woman in the purple dress, mourning her lost cat, the junk pile becomes a hiding place for both pain and hope, culminating in the discovery of a kitten beneath the last piece of trash. Lucas, too, has his own baggage—his refusal to engage, his obsessive order, and his fear of emotional mess.

As the community carries off the pile, piece by piece, there is a subtle yet powerful sense of shared cleansing. The cleanup becomes therapeutic, not because it restores physical order, but because it signifies the release of something internal.

The story illustrates that healing is not always logical or direct; it often requires rituals of absurdity and shared nonsense. The emotional baggage people carry cannot always be articulated or rationally addressed, but it can sometimes be lifted through strange, communal acts that allow them to confront what they’ve buried.

In this way, the trash pile is not a problem to be solved but a symptom of deeper, collective exhaustion—and its removal, a quiet but powerful form of letting go.

Resistance, Rebellion, and Personal Agency

Lucas’s evolution from passive recluse to reluctant leader and, eventually, to trickster figure embodies a journey of resistance and reclaiming agency. His initial refusal to participate in community life is an act of passive rebellion against a world that demands emotional labor and conformity.

However, the frying pan incident forces him into the very structures he seeks to avoid. His appointment to the Pile Committee and subsequent entanglement in online communities reflect how systems often co-opt individuals without consent.

Yet Lucas finds subtle ways to subvert these structures. His use of reverse psychology—manipulating Facebook cults into cleaning the pile out of either reverence or anger—is a clever rebellion against both social media frenzy and civic apathy.

It marks a shift from avoidance to strategic engagement, where he chooses his methods and exerts influence without sacrificing his core desire for autonomy. His final act of pretending to fall into a coma mirrors the earlier action of the woman in the green shirt, but unlike hers, his is not an escape born of burnout but a conscious act of boundary-setting.

It’s his way of saying no—no to forced responsibility, no to the chaos of collective nonsense, and yes to choosing his own terms of interaction. The story thus becomes a nuanced exploration of how people can resist without retreating completely, how rebellion doesn’t always mean loud defiance, and how even satire and subversion can be acts of personal truth.

Through Lucas, the book suggests that reclaiming agency isn’t about rejecting the world, but about finding one’s place in it on one’s own terms.