The Art of Vanishing Summary, Characters and Themes

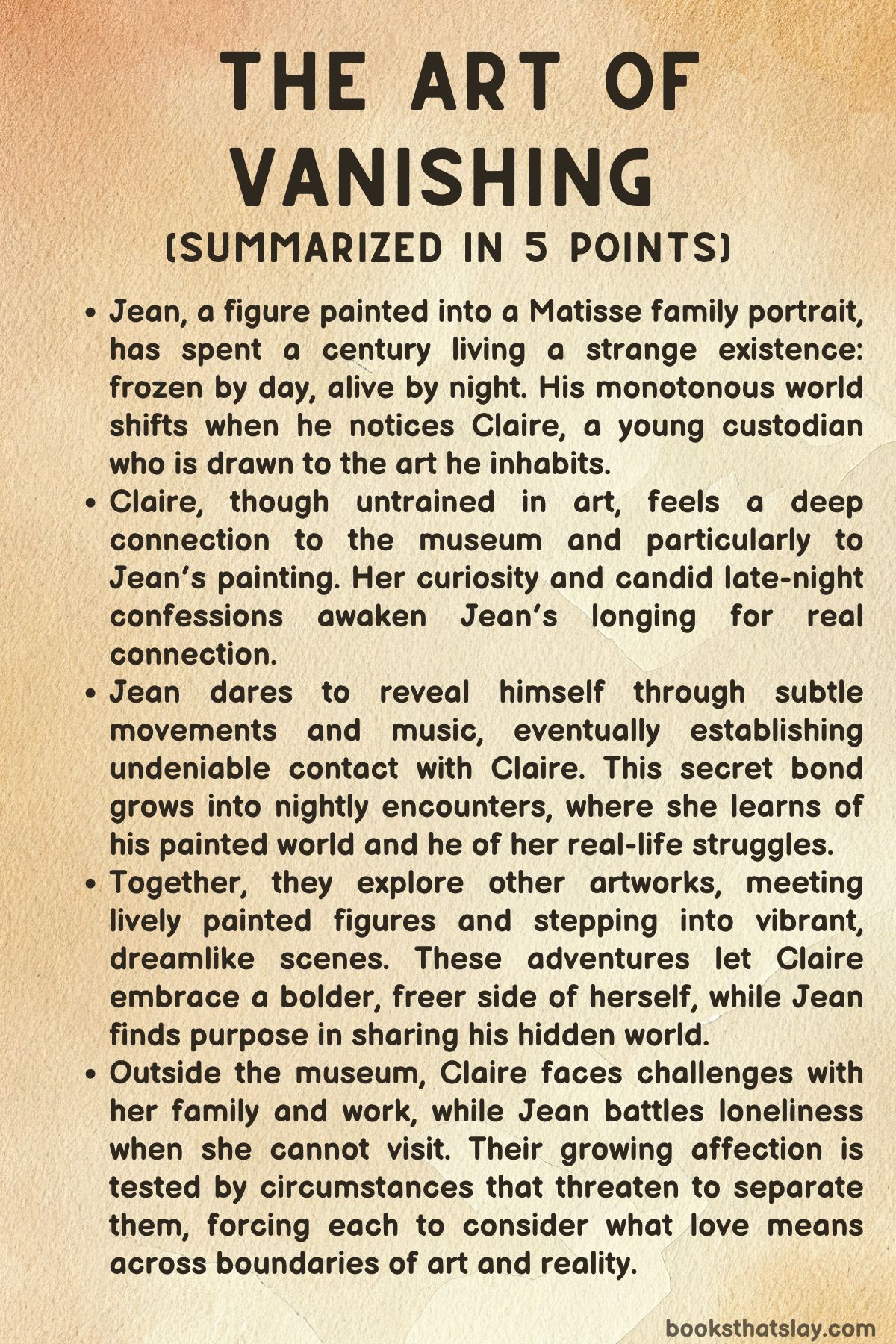

The Art of Vanishing by Morgan Pager is a work of magical realism that explores the fragile boundary between art and life. It follows Jean, a man trapped inside a Matisse painting, and Claire, a museum custodian who unknowingly awakens his century-long stillness.

As their bond grows, the novel examines themes of longing, identity, memory, and the power of imagination to reshape reality. Through a narrative that shifts between the vibrant, hidden lives of painted figures and the everyday struggles of a modern woman, the story asks how love, art, and human connection can transcend time and physical barriers.

Summary

Jean, a painted figure within Henri Matisse’s 1917 family portrait, has spent a century frozen by day and alive only at night within the painted confines of his world. He is joined by his siblings, Marguerite and Pierre, and their mother.

Though he once accepted the monotony of his existence, his life changes when Claire, a new custodian at the museum, arrives. Unlike others, she radiates curiosity and wonder.

She lingers before artworks with fascination, often whispering her thoughts into the empty galleries. Jean notices that her gaze repeatedly rests on him, stirring a longing he has not felt in decades.

While Claire adapts to the laborious work under Linda, her trainer, she also reveals her insecurities and dreams to the silent museum walls. She shares her exhaustion, her modest life, and even affectionately calls Jean “handsome.

” Encouraged by her openness, Jean dares to break his silence by playing a violin left in his painted world. Though she cannot hear the sound, Claire senses something alive within his painting and responds, deepening their connection.

As their secret companionship grows, Jean finally finds a way to touch her through the canvas. Claire, though frightened, reaches back, and together they breach the invisible boundary.

Soon, she discovers she can step fully into his painted realm. Inside, she meets his family and other figures who roam between artworks at night.

Jean guides her through painted gardens, sculptures, and entire scenes bursting with life. Claire, though wary, is exhilarated by the freedom these painted worlds provide.

At a vivid revelry within another Matisse masterpiece, she dances, drinks, and experiences joy she has long suppressed in her real life.

The relationship between Claire and Jean quickly deepens. They walk hand in hand through landscapes, sharing their pasts.

Claire confides about her childhood fascination with art, her struggles as a single mother, and her symbolic ring that hints at a complicated history. Jean recounts being painted before his father left for war, and his subsequent century of longing for a life beyond the frame.

Their intimacy grows until they finally kiss, confirming a love neither expected. Claire embraces her bolder self inside the paintings, removing her ring to signal a new chapter in her life.

Together they continue exploring, visiting racetracks and beaches within painted canvases, where Claire feels liberated from the weight of her everyday struggles. At a seaside cottage, their relationship turns tender and passionate.

Though uncertain of the consequences, they choose to embrace the love blossoming between them.

But Claire’s real life intrudes. She loses her job at the museum when government shutdowns force temporary closures.

Suddenly cut off from Jean, she must return her full attention to her daughter Luna and grandmother Gracie. Jean, meanwhile, suffers within the silent galleries, desperate for her return.

In her absence, he reconnects with Odette, a figure from another painting and once a companion. Their conversations underscore the loneliness of those trapped in art and the different ways they cope with isolation.

Claire’s life grows more complicated when Jeremy, Luna’s estranged father, reappears, wanting involvement in his daughter’s life. Distrustful but willing to listen for Luna’s sake, Claire balances these pressures while yearning for Jean.

At the same time, the museum prepares for reopening, with staff returning under new protocols. Hope stirs in Jean that Claire may return.

Then, a mysterious journal is introduced into the gallery as a new exhibit, displayed on a pedestal and turned page by page. When it is suddenly stolen, the museum becomes the center of media frenzy.

FBI agents investigate, and suspicion falls on staff. Unbeknownst to them, Claire has taken the journal, hiding it at home after feeling an inexplicable pull toward it.

Reading it, she discovers a profound link to Odette, who once had the same ability to cross between worlds.

Claire eventually reveals her secret daughter to Jean, deepening their bond but also highlighting the impossibility of abandoning her real life. The pressure mounts as the FBI agent grows suspicious, and Jamie, the museum president, secretly witnesses Claire’s ability to step into paintings.

Instead of exposing her, Jamie grants her the space to say goodbye.

Claire and Jean share a final, painful farewell. She knows her responsibilities to Luna outweigh the impossible love she has found, but she entrusts the stolen journal to Odette, who promises to safeguard it.

Odette reveals her own history of crossing between worlds and assures Claire that Jean’s love is singular.

Years pass. Jean channels his grief into writing, recording his experiences and sharing them among painted peers, creating a chronicle of their hidden existence.

His sister Marguerite admires his work, encouraging him to continue. Eventually, Claire returns—not as a custodian, but as a visitor with her daughter.

Their reunion is tender and brief, filled with unspoken recognition. Jean sees the strength she has gained, while Luna gazes with awe at the painting that once held her mother’s secret.

The novel closes with Jean, comforted by memory and the permanence of art, Odette reunited with her journal, and the acknowledgment that while their worlds remain apart, the love and connection forged between Claire and Jean will endure through writing, memory, and the timelessness of art itself.

Characters

Jean

Jean is the central figure of The Art of Vanishing, a young man painted into Henri Matisse’s family portrait of 1917, and the novel’s emotional anchor. Though frozen in youth for over a century, Jean embodies a mix of nostalgia, yearning, and resilience.

Initially, his existence is defined by monotony—confined to the painting, trapped in endless observation of museum visitors, and numbed by repetition. Claire’s arrival radically disrupts this inertia, awakening within him a dormant passion for life and human connection.

Jean is deeply sensitive, an observer who turns longing into poetry, but he also displays courage as he risks breaking the barrier between art and reality. His arc evolves from a passive dreamer to an active seeker of love and experience, determined to grasp meaning even within his fragile, painted reality.

His relationships with Claire, Odette, and his siblings reveal a man both vulnerable and deeply loyal, one who finds redemption in love yet understands the weight of impermanence.

Claire

Claire stands at the heart of the human world in The Art of Vanishing, her story intertwining with Jean’s in ways both magical and poignant. At first, she appears modest and unassuming, a young woman taking on a night job at the museum while balancing the demands of caring for her daughter Luna and her grandmother Gracie.

Yet beneath her quiet demeanor lies an intense sense of wonder, curiosity, and emotional depth. Her instinctive attraction to the art, especially Jean’s painting, hints at her openness to imagination despite the weight of her practical struggles.

As she confides in Jean’s silent portrait, her vulnerability becomes a strength—allowing her to forge a bond that transcends reality. Claire is torn between her responsibilities in the real world and the freedom she discovers in the painted one, but she ultimately demonstrates maturity, choosing family and duty even at the cost of heartbreak.

Her journey reveals her as a character of resilience, caught between longing and responsibility, yet enriched by the love she dares to embrace.

Marguerite

Marguerite, Jean’s sister within the painting, serves as both confidante and cautious guardian in the narrative. Where Jean is impulsive and romantic, Marguerite is pragmatic, carrying the weight of their shared confinement with quiet strength.

She warns Jean against revealing himself to Claire, embodying the voice of reason that tempers his reckless pursuit of connection. At the same time, her compassion is evident in the way she consoles Jean during his moments of despair, particularly when Claire is absent.

Marguerite embodies endurance—her presence a reminder of the family bond that anchors Jean even as he reaches for something beyond their painted reality. Though her role is more restrained than Jean’s, she represents the wisdom of acceptance and the quiet heroism of survival in stasis.

Pierre

Pierre, the youngest sibling in the portrait, plays a more peripheral but symbolic role in the story. His presence underscores the family dynamic within the painted world, though he is less emotionally developed than Jean or Marguerite.

Pierre serves as part of the larger tapestry of Matisse’s creation, representing the innocence and timelessness captured in paint. While Jean’s longing defines the central narrative, Pierre reminds readers of the other lives tethered within the frame, bound to the same strange existence yet responding to it in quieter ways.

His character reflects continuity and the way even those less vocal contribute to the shared burden of immortality within art.

Odette

Odette is one of the most compelling figures in The Art of Vanishing, a woman from another painting who once shared an intimate bond with Jean. She is worldly, wise, and tinged with sorrow, embodying the complexity of living for centuries within frames.

Unlike Jean, who clings to yearning, Odette has experienced cycles of passion and loss, giving her a more pragmatic view of existence. Her reappearance during Claire’s absence underscores the themes of memory, companionship, and survival.

Odette offers Jean both comfort and challenge—she is living proof that love can be both transformative and fleeting in their peculiar existence. Her safeguarding of the journal and her revelation of once having shared Claire’s gift position her as a bridge between past and present, human and painted, memory and permanence.

Odette is a mirror to Jean’s romanticism, her presence deepening the story’s exploration of love, resilience, and the impermanence of even immortal beings.

Linda

Linda, the seasoned cleaning staff member who mentors Claire, provides a grounding presence in the narrative. Through her, the book captures the ordinary struggles of working-class life, contrasting sharply with the fantastical elements of the painted world.

Linda’s resilience, shaped by hardship, reflects a life of labor and endurance, yet she maintains a kind of wisdom that Claire relies on in her early days at the museum. Her role emphasizes the theme of invisible caretakers—those who sustain the spaces that others merely pass through.

Linda’s presence reminds us that even in a story filled with magical crossings between art and reality, the weight of everyday struggle remains central to human experience.

Jamie Leigh

Jamie Leigh, the museum president, occupies a peripheral but symbolically significant role. As an administrator, she represents the institutional lens through which art is managed, displayed, and controlled.

Yet her unexpected choice to protect Claire upon discovering her secret marks her as more complex than a mere bureaucrat. Jamie embodies the negotiation between authority and empathy, practicality and wonder.

By granting Claire the space to say goodbye to Jean, she becomes an unlikely ally, highlighting how even figures of authority can recognize and honor the ineffable connections that art inspires.

Luna

Luna, Claire’s young daughter, remains largely on the margins of the magical events but is essential in defining Claire’s choices. As a child, she embodies innocence, curiosity, and the future that Claire must prioritize over her own desires.

Luna’s presence gives weight to Claire’s sacrifices and grounds her in the realities of love, duty, and family. In her final appearance with Claire at the museum years later, Luna’s awe at Jean’s painting reflects a generational continuation of wonder.

Through her, the novel reinforces the tension between fleeting personal passion and enduring familial bonds.

Gracie

Gracie, Claire’s grandmother, stands as another anchor in her real-world life. Her presence offers stability and continuity, particularly during the lockdown when Claire’s world begins to unravel.

Gracie is practical and nurturing, her quiet resilience echoing the generational strength that sustains Claire. Though she does not directly interact with Jean’s world, her role as caregiver underscores the importance of family legacy and the sacrifices made across generations.

She represents a counterbalance to Claire’s escapist desires, embodying the roots that tether her to reality.

Themes

Art as a Living World

In The Art of Vanishing, art is not a static object to be admired from a distance but a dynamic, breathing world that holds the essence of those it depicts. The story grants agency to painted figures, allowing them to move, feel, and converse after hours, turning the museum into a liminal space between reality and imagination.

Through Jean’s existence within Matisse’s painting, art becomes a metaphor for immortality as well as confinement. While Jean gains eternal life within the brushstrokes, he is also trapped within their boundaries, able only to watch generations of visitors come and go.

Claire’s ability to cross into this world complicates the divide between viewer and subject, raising questions about the permeability of art and life. For Claire, art becomes a refuge from exhaustion, work, and uncertainty, while for Jean, it becomes both his cage and the only medium through which he experiences connection.

The museum is no longer simply an archive of the past; it transforms into a living ecosystem of voices, memories, and suppressed longings. This theme highlights how art can transcend its material state, holding not only the vision of its creator but also the potential for new meaning when engaged by those who truly see it.

The novel suggests that to encounter art deeply is to risk seeing it as more than representation—something that might reshape how we understand existence itself.

Loneliness and Connection

Jean’s century-long isolation inside the frame reflects the weight of solitude, a stillness punctuated only by fleeting gazes of museum visitors. His initial resignation to endless monotony underscores how loneliness corrodes identity, leaving him clinging to fragments of meaning such as rereading the same book page for decades.

When Claire enters his orbit, her very presence revives his yearning for connection, proving that human contact, even across impossible boundaries, has the power to restore vitality. Claire, too, embodies loneliness—her quiet struggles as a single mother, her physical fatigue from the cleaning job, and her unspoken discontent about her limited horizons mirror Jean’s sense of confinement.

The bond they form transcends physical and temporal barriers, suggesting that genuine connection arises not from convenience but from recognition of shared vulnerability. The theme underscores the hunger for intimacy that exists beneath appearances, and how people, regardless of their worlds, long to be seen and heard.

Their relationship is charged with risk, secrecy, and the impossibility of permanence, yet it affirms that even fragile connections can alter one’s sense of self. In many ways, the story proposes that loneliness is not merely the absence of company, but the absence of being understood—and in Jean and Claire’s recognition of one another, both find a brief but transformative reprieve.

Boundaries Between Reality and Imagination

The novel consistently destabilizes the line separating tangible life from imagined possibility. Jean’s painted existence challenges the conventional understanding of what constitutes reality, while Claire’s ability to cross into his world positions imagination as a gateway to deeper truths.

The theme insists that the boundary between art and life is porous, that what is thought to be unreal can shape real emotions, choices, and even futures. Claire’s double existence—balancing the demands of her daughter and grandmother while nurturing an impossible romance with a man of pigment and canvas—illustrates how the human mind navigates between practical necessity and inner yearning.

Her crossing into painted landscapes is not simply escapism; it represents a reclamation of wonder in a life otherwise reduced to survival. The theft of the mysterious journal later in the story heightens this theme, as objects and texts themselves possess hidden worlds that influence reality.

The line blurs further when even Jamie, the museum president, perceives Claire’s crossing into art, acknowledging that imagination has material consequences. Ultimately, the narrative argues that imagination is not secondary to reality but an essential part of it, reshaping how people define their existence and relationships.

The world of paintings may be unreal in the conventional sense, but its impact on Jean and Claire is undeniable, proving that lived experience is not bound by conventional definitions of what is real.

Time, Memory, and Permanence

Time in The Art of Vanishing operates differently for Jean than for Claire. For Jean, life is endless repetition—frozen during the day, released only at night, untouched by aging but weighed down by monotony.

For Claire, time moves swiftly, marked by exhaustion, financial worry, and her responsibilities to Luna and Gracie. Their relationship highlights the painful asymmetry of time—Jean will remain young and unchanging, while Claire moves through the stages of life.

This contrast illuminates the fragility of human memory and the desperate urge to preserve fleeting connections. When Jean begins writing his story after Claire’s departure, it becomes a way of asserting permanence against the erosion of time.

His words are not only for himself but for his painted peers, offering a collective memory to withstand isolation. Claire, meanwhile, navigates the pressing immediacy of real-world crises—unemployment, single parenthood, and an absent partner—yet still returns to Jean, proving that memory itself can be a form of endurance.

Their final reunion years later with Luna demonstrates that though worlds may diverge, memory preserves the emotional truth of their bond. The theme asserts that permanence does not lie in possession or continuity, but in the way memory carries love across time and across boundaries that cannot be crossed again.

Love and Sacrifice

At the heart of the novel lies a love story defined as much by separation as by intimacy. Jean and Claire’s romance blossoms under impossible circumstances, yet its intensity grows precisely because of the fragility of their meetings.

Their passion is never just about desire—it is steeped in longing, secrecy, and the constant awareness that their worlds cannot fully merge. Sacrifice underscores their relationship from the beginning: Jean risks revealing himself to Claire despite Marguerite’s warnings, while Claire sacrifices her safety and stability by keeping the secret of the paintings.

When she must ultimately leave him to prioritize Luna, the decision demonstrates how love often requires relinquishment. True affection, the narrative suggests, is measured not by permanence but by the willingness to act in the other’s best interest, even when it brings personal loss.

Claire’s farewell embodies this—choosing her child over her impossible romance—while Jean’s decision to preserve her in memory and writing reveals love’s persistence beyond physical presence. Their final reunion years later confirms that love need not be constant to be real; it exists in the recognition that even transient moments of intimacy can define a lifetime.

In this way, the story elevates sacrifice as not the end of love, but its truest expression.