The Art Thief Summary and Analysis

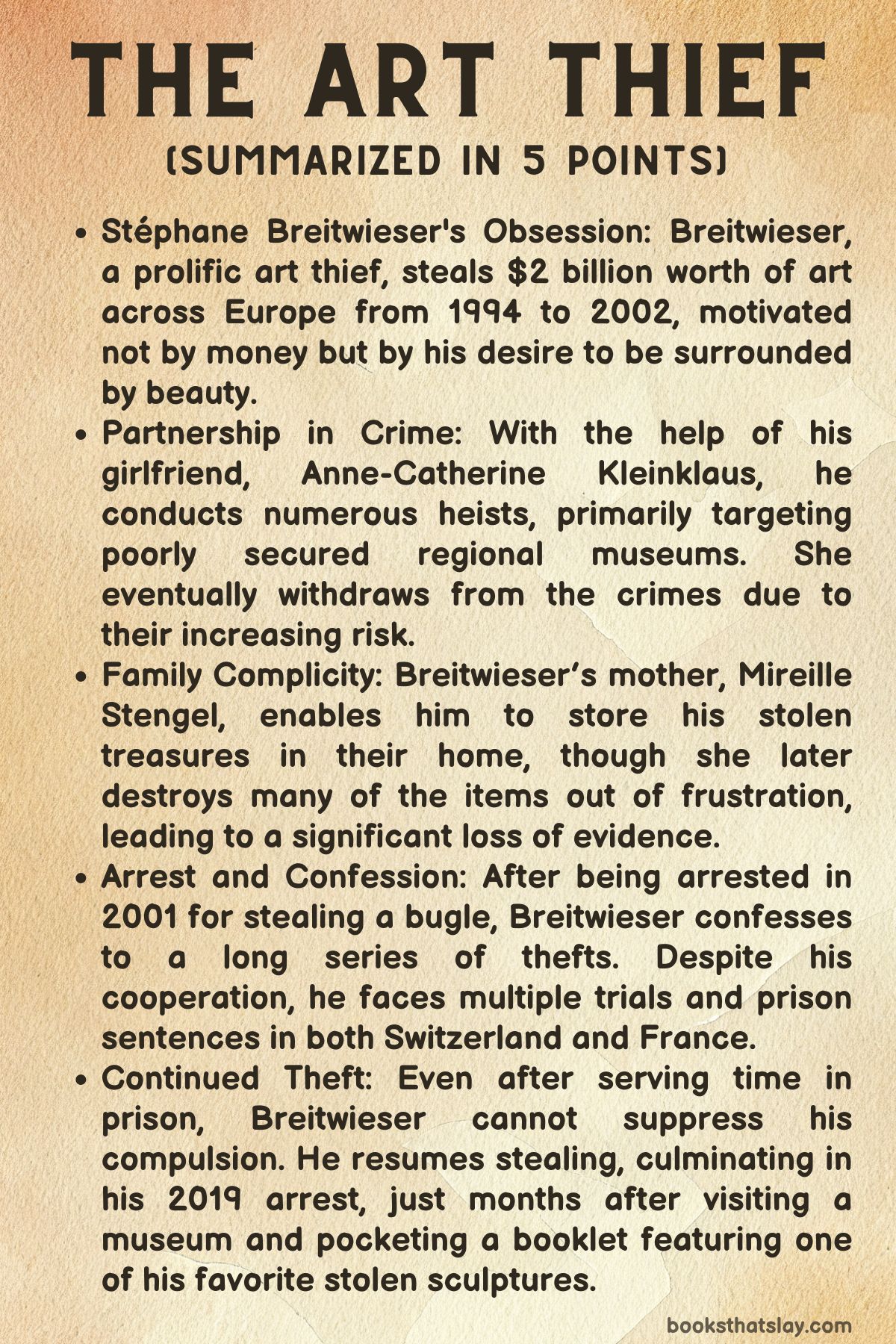

The Art Thief by Michael Finkel offers a riveting dive into the life of Stéphane Breitwieser, one of the most notorious art thieves in history. Between 1994 and 2002, Breitwieser committed a staggering series of heists across Europe, stealing nearly $2 billion worth of priceless artwork—not for money, but to surround himself with beauty.

Finkel’s narrative blends true crime with a psychological study of a man driven by obsession. The book not only explores the intricacies of Breitwieser’s audacious thefts but also reveals the impact on those closest to him, especially his mother and girlfriend, who were caught in his web of crime.

Summary

Stéphane Breitwieser’s early years shape his passion for art and antiquities. Growing up in a home filled with relics, he finds solace in digging for artifacts with his grandfather, retreating from his authoritarian father.

When his parents divorce, he moves into a modest apartment with his doting mother, Mireille Stengel. They live off welfare, with his mother enabling his growing obsession with collecting treasures.

His first theft occurs during a brief museum job, where he impulsively pockets an ancient belt buckle, igniting a compulsion that will define his life.

In 1991, Breitwieser meets Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus, who becomes his partner in both life and crime.

They move into the attic of his mother’s house, and soon begin stealing valuable objects from museums and galleries. Their first joint theft happens in 1994 when they take an 18th-century pistol.

Emboldened, they expand their operations, targeting lesser-known museums with poor security. Anne-Catherine plays a key role in their heists, often deciding when to call off risky jobs. They maintain a facade of affluence by dressing in designer clothes, managing to avoid suspicion.

Meanwhile, Breitwieser fills the attic with stolen art, including his prized ivory sculpture, Adam and Eve, which he keeps by his bedside.

As their heists increase, Anne-Catherine grows cautious. When Breitwieser ignores her warnings and steals from a Swiss gallery in 1997, they are arrested, given suspended sentences, and banned from Switzerland.

The strain of the arrest, along with Anne-Catherine’s secret abortion, leads to a temporary separation. After reconciling, Anne-Catherine refuses to assist in any more thefts, though Breitwieser continues, secretly targeting Swiss museums.

In November 2001, after Breitwieser foolishly steals a bugle without gloves, Anne-Catherine insists on returning to the scene to erase his fingerprints. They are caught, and Breitwieser is arrested.

Under interrogation, he confesses to numerous thefts, believing his cooperation will reduce his sentence. However, when the police search his home, the attic is empty. His mother, furious at the trouble he’s caused, had destroyed or discarded the stolen art.

Breitwieser faces multiple trials. In Switzerland, he receives a four-year sentence, and in France, he is sentenced to two more years.

His relationships unravel as Anne-Catherine moves on with her life, and his mother is jailed for her role in concealing the crimes. After his release, Breitwieser continues his thieving ways, even as he briefly tries to rehabilitate himself by publishing a memoir, which flops.

Despite several more arrests, his obsession persists. In a bizarre twist, just before a 2019 arrest, he visits a Belgian museum with Michael Finkel, where he steals a booklet featuring his favorite stolen sculpture, Adam and Eve.

The art thief, it seems, can never quite resist his urge to steal.

Characters

Stéphane Breitwieser

Stéphane Breitwieser is the central figure of The Art Thief and one of the most unusual art thieves in history. His motivations are not financial but aesthetic, driven by an intense desire to surround himself with beauty.

He grows up as a loner, immersed in a world of antiquities through his grandfather and mother, who nurtures his interest in historical artifacts. His upbringing is marked by emotional isolation, and while his father is authoritarian, his mother is indulgent, setting the stage for his complex relationship with authority and rebellion.

Breitwieser’s life of crime begins with a small theft while working as a museum guard, and his compulsion grows from there. His love affair with Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus becomes the catalyst for his prolific career as a thief.

Their partnership is highly functional but toxic, relying on her careful judgment and his obsessive drive to steal. Breitwieser’s acts of theft are more about control and possession than financial gain.

The breakdown of his relationship with Anne-Catherine signals his increasing destructiveness. His attachment to a small ivory sculpture of Adam and Eve reflects his obsessive need to possess art.

Despite brushes with the law, he is unable to stop stealing, believing that honesty will earn him leniency. His thefts continue even after serving time, indicating his compulsive behavior and detachment from reality.

Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus

Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus is Breitwieser’s girlfriend and accomplice in the early years of his thefts. Initially, she plays a key role, helping them blend into wealthy surroundings and often moderating the risks.

However, her tolerance for Breitwieser’s recklessness wanes as he becomes more dangerous. After their arrest in Switzerland, she refuses to participate in further thefts, marking a turning point in her moral boundaries.

The abortion she has without his consent shows her need to reclaim control over her life. Breitwieser’s violent response, combined with his increasing recklessness, leads to the eventual breakdown of their relationship.

By the end of the narrative, Anne-Catherine distances herself entirely from Breitwieser. She moves on, starting a new life with another man and a child, and eventually testifies against him in court.

Mireille Stengel

Mireille Stengel, Breitwieser’s mother, plays a crucial role in shaping his life. She indulges his eccentricities and provides financial support long after he should be independent.

Though she does not encourage theft directly, her passive acceptance of his stolen art reflects a willful ignorance. Their close bond is evident, with Stengel providing a safe haven for Breitwieser’s stolen goods.

After his arrest, her emotional volatility is revealed when she destroys his collection of stolen artwork. This act mirrors Breitwieser’s own erratic behavior and represents her attempt to sever ties with his criminal life.

Despite her efforts to protect her son, Stengel is held accountable for her involvement and serves a brief prison sentence. Her story reflects the conflict between loyalty to her son and self-preservation.

Stéphanie Mangin

Stéphanie Mangin enters Breitwieser’s life after Anne-Catherine, offering a brief period of stability. However, when she discovers a stolen painting in their home, Mangin takes immediate action.

Unlike Anne-Catherine, she refuses to tolerate Breitwieser’s behavior. She reports him to the police, showing her strong moral stance and desire to distance herself from his criminal activities.

Mangin represents a sharp contrast to the enabling relationships Breitwieser had previously. Her quick decision to turn him in underscores her unwillingness to be complicit in his crimes.

Vincent Noce

Vincent Noce, a journalist, plays an external role in Breitwieser’s story by publishing The Selfish Collection, a critical book about him. Noce’s perspective challenges Breitwieser’s romanticized image of himself.

While Breitwieser sees himself as a misunderstood aesthete, Noce presents him as narcissistic and selfish. This contrast between self-perception and societal judgment is central to the narrative.

Noce’s work serves as a direct response to Breitwieser’s memoir, Confessions of an Art Thief, which had received poor reviews. By publishing his book, Noce ensures that Breitwieser is seen as a deeply flawed figure.

Stéphane Breitwieser’s Father

Though a minor figure, Breitwieser’s father influences his development. Described as authoritarian and emotionally distant, his strictness contrasts with his mother’s indulgence.

This dynamic likely contributes to Breitwieser’s rebellion and isolation. The absence of a positive paternal figure may have driven him toward escapism through art and theft.

His father’s influence, while indirect, plays a role in shaping Breitwieser’s need for control and difficulty with authority. This distant relationship is key to understanding his complex personality.

Analysis and Themes

The Paradox of Aesthetic Devotion and Criminality: The Thief’s Dual Pursuit of Beauty and Destruction

In Michael Finkel’s The Art Thief, Stéphane Breitwieser’s thefts are driven not by financial motives but by a deep, obsessive desire to possess and surround himself with objects of beauty. This sets up a profound paradox: Breitwieser, a man so enamored with art’s aesthetic value, commits acts that desecrate the very institutions meant to protect and display these works.

His criminal acts undermine the cultural preservation of the very art he claims to revere. The dichotomy of his actions—stealing masterpieces while professing admiration for them—reveals an unstable relationship between art appreciation and selfish possession.

Breitwieser’s compulsion exposes the tension between public stewardship of cultural treasures and private desire. His crimes obliterate the communal experience of art, transforming it into a solitary and secretive pursuit, thereby violating the shared cultural significance that art represents.

This paradox is ultimately a destructive form of devotion, one that dismantles the broader societal value of art while amplifying the thief’s narcissistic obsession with beauty.

The Disintegration of Moral Boundaries Through Emotional Manipulation and Codependency

A central theme in The Art Thief is the manipulation and emotional entanglement that characterizes the relationship between Breitwieser and Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus. Their partnership is emblematic of codependency that exacerbates moral dissolution.

Anne-Catherine initially participates in the thefts but later becomes the voice of caution, insisting on moderation and pulling back from the crimes when the stakes grow too high.

Yet, Breitwieser’s psychological hold on her, demonstrated through emotional manipulation and acts of violence—such as slapping her after learning of her abortion—deepens the moral quagmire in which they both become mired.

Their relationship is an intricate study in how personal dynamics and emotional dependencies can blur ethical lines, turning love and loyalty into tools for criminal complicity.

Anne-Catherine’s eventual break from Breitwieser highlights how such manipulation can have long-lasting repercussions, trapping individuals in cycles of self-destruction even as they attempt to extricate themselves.

Maternal Enablement and Destruction: The Collapse of Familial Duty into Complicity and Betrayal

Mireille Stengel, Breitwieser’s mother, plays a contradictory role in his life—both as an enabler of his behavior and a figure of ultimate betrayal.

The relationship between mother and son reveals a complex dynamic of indulgence and destruction.

Stengel indulges her son’s increasingly pathological behavior, allowing him and his girlfriend to live rent-free in her attic and offering little challenge to the growing collection of stolen goods in her home.

Her blind indulgence can be seen as a perverse form of maternal loyalty, one that allows her son’s criminality to flourish unchecked.

However, her later destruction of Breitwieser’s stolen art—disposing of his treasures in a fit of anger—marks a sharp turn from enablement to active betrayal. This act is deeply symbolic: the person who once protected him from consequences now becomes the catalyst for the collapse of his empire of stolen art.

The relationship between Breitwieser and his mother thus illuminates the fragility of familial bonds when subjected to the pressures of criminal behavior and personal disillusionment.

The Fragility of Identity in the Pursuit of Cultural Ownership: Art as a Reflection of Personal and Societal Insecurities

The thefts in The Art Thief are not simply acts of criminality but are also symbolic of Breitwieser’s quest to construct and affirm his identity through art.

His repeated claims that the stolen pieces are not for financial gain but to fulfill an emotional and aesthetic void underscore his fragile sense of self.

Breitwieser’s identity becomes entwined with the works he steals, as though the acquisition of these masterpieces gives him a sense of worth and purpose that he cannot find through conventional means.

This obsession is compounded by his lack of financial stability, his dependence on his mother and government welfare, and his inability to sustain meaningful personal relationships.

His inability to appreciate art for its broader cultural and historical value reflects a deeper societal insecurity—one that seeks validation not through community and shared experience but through the hoarding of beauty.

This theme speaks to a larger critique of cultural ownership and the ways in which individuals, in their desperation for identity and meaning, can appropriate and privatize what is meant to be collectively cherished.

The Displacement of Moral Accountability Through Legal and Psychological Deflection

Breitwieser’s trial and subsequent confessions reveal a consistent pattern of deflecting responsibility, both legally and psychologically.

His repeated claims that Anne-Catherine opposed his thefts and that his mother was unaware of them serve as attempts to mitigate his culpability, portraying himself as someone misunderstood and unfairly judged.

This tactic of deflection exposes the complexities of moral accountability within the framework of criminal justice.

Breitwieser’s confession strategy—where he believed honesty would reduce his sentence—reflects a distorted perception of justice, one in which he seeks to manipulate the system for personal advantage rather than fully confronting the weight of his actions.

His later attempts to re-enter society, including his poorly received memoir and brief periods of reformed behavior, further illustrate his inability to fully internalize responsibility for his crimes.

This deflection is not just a personal failing but reflects a broader societal question about how justice, guilt, and rehabilitation are negotiated in cases of non-monetary crime, where psychological motives are as central as legal transgressions.

The Erosion of Trust in Personal and Public Institutions: Museums, Relationships, and the Aftermath of Cultural Violation

Breitwieser’s actions undermine not only the sanctity of art museums but also the very idea of trust in public institutions. Museums, churches, and galleries—places designed to protect and display cultural heritage—are turned into vulnerable targets, revealing the fragility of these institutions in the face of personal greed and obsession.

On a more intimate level, his relationships—whether with Anne-Catherine or his mother—are based on a tenuous balance of trust and betrayal. These violations of trust, both public and personal, create ripple effects that go beyond the immediate consequences of the thefts.

The story of Breitwieser’s actions thus becomes a meditation on the broader societal implications of broken trust, where institutions designed to safeguard culture and relationships meant to offer emotional support become entangled in a web of deceit, complicity, and destruction.

The damage is not limited to the stolen artworks but extends to the fabric of the relationships and institutions Breitwieser interacts with, leaving a legacy of mistrust and erosion.