The Bombshell by Darrow Farr Summary, Characters and Themes

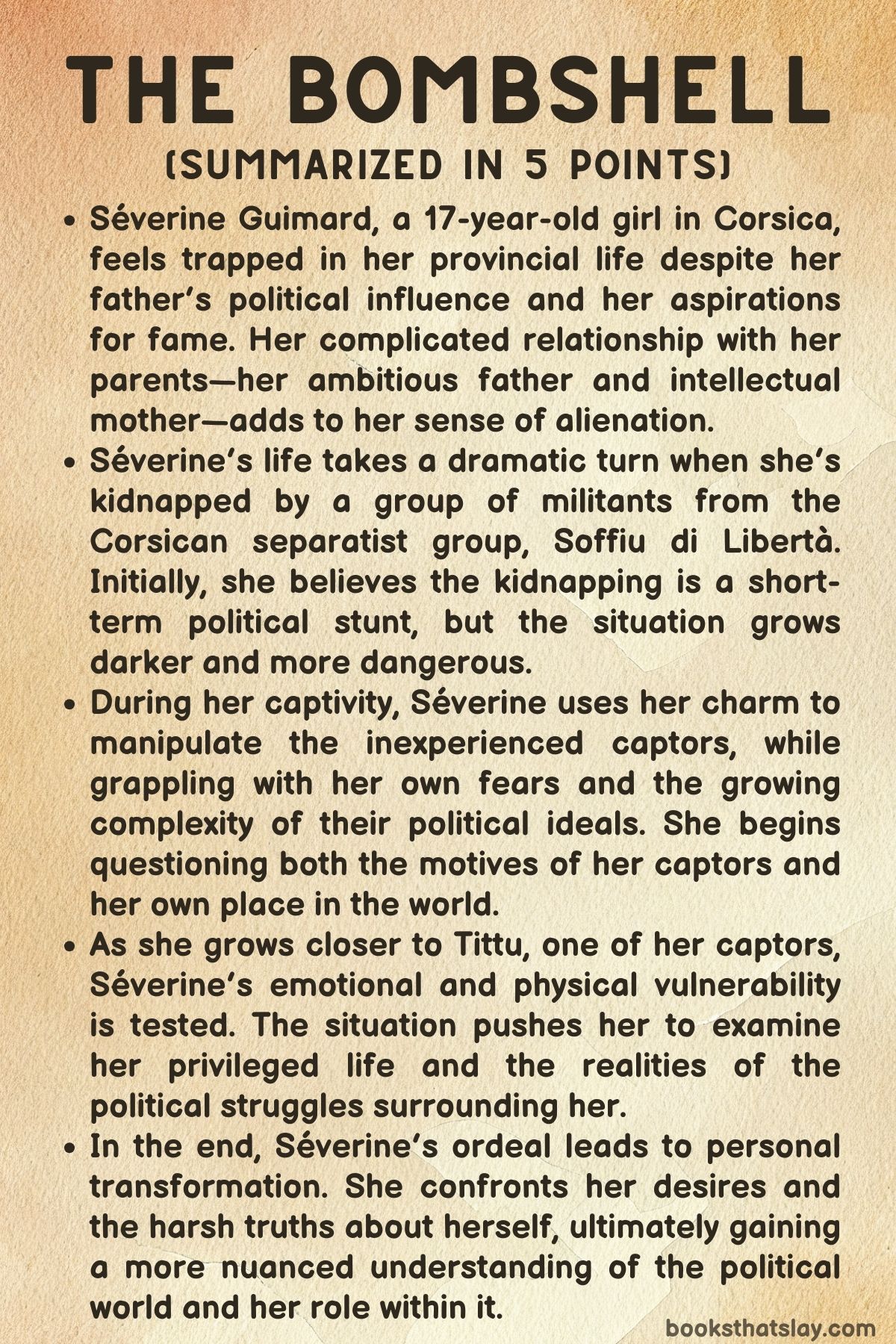

The Bombshell by Darrow Farr is a complex narrative exploring the intersection of identity, power, and political conflict, set against the backdrop of Corsica’s struggles for independence. The novel revolves around Séverine Guimard, a seventeen-year-old girl born into a family marked by political prominence.

While she yearns to escape her provincial life for the glitz of Paris or Hollywood, her world is upended when she becomes a pawn in a Corsican separatist kidnapping plot. As Séverine grapples with her captivity and ideological clashes with her captors, she embarks on a journey of self-discovery and survival, ultimately questioning her ambitions and identity in a politically charged environment.

Summary

The story of The Bombshell follows Séverine Guimard, a seventeen-year-old girl living on the island of Corsica, where her father, Paul Guimard, serves as the prefect. Although she enjoys the privileges of her father’s political stature, Séverine feels disconnected from her life on Corsica.

Her sharp features, including a large nose, make her stand out, but she does not feel a sense of belonging. Séverine’s heart yearns for the glamour of Paris or Hollywood, and her ambition is to leave behind the pressures of the provincial life and the expectation to pass her baccalauréat exams.

Despite her mother’s intellectual influence, Séverine is fixated on fame, using her allure to manipulate boys like Antoine Carsenti, a classmate infatuated with her.

However, her world is turned upside down when she is kidnapped by a group of militants from Soffiu di Libertà, a Corsican independence group. Initially, Séverine believes her kidnapping is a short-term political maneuver designed to pressure her father, but she soon learns that it is far more dangerous.

The militants are inexperienced, and as the situation becomes increasingly chaotic, Séverine is subjected to days of confinement, isolation, and fear. The group demands a ransom, but the kidnapping evolves into a more intense ordeal as the captors’ actions grow more unpredictable.

Despite the grim situation, Séverine is able to reflect on her life, her family, and her place in the world.

Among the captors is Bruno, the leader, who vacillates between acting as a hard-line revolutionary and revealing signs of internal conflict. Séverine attempts to manipulate her captors, using her charm to her advantage despite the vulnerabilities she faces.

While she initially questions the motivations of her captors, particularly their ideological stance, her survival instincts drive her to understand the inner workings of their struggle. The captors are a mixture of experienced revolutionaries and amateurs, and their group’s internal conflicts only add to the volatility of Séverine’s situation.

As she learns more about their beliefs and backgrounds, Séverine becomes both a participant and a bystander in the ideological struggle around her.

As the days pass, Séverine begins to question her own sense of entitlement and power. Her life, once defined by her status and the control she exerted over boys like Antoine, now seems fragile and uncertain.

Despite the humiliation she endures, Séverine refuses to break. She starts to bond with Tittu, another one of her captors, whose vulnerability stands in stark contrast to the hardened image of the other militants.

Their developing connection brings to light the complex nature of Séverine’s captivity and forces her to confront her own desires and longings for freedom.

The turning point in Séverine’s ordeal comes when she begins to manipulate the division within the group. With their lack of experience and internal conflicts, Séverine seizes the opportunity to sow discord among the captors.

Through clever tactics, she weakens their resolve and creates an opening for her escape. As her captors’ grip on her weakens, Séverine grows more confident in her ability to reclaim control over her fate.

The power dynamics shift, and she uses her intellect and charm to her advantage. Her strategic manipulation of her captors marks a critical moment in her journey towards freedom.

In a tense moment, Séverine faces a difficult confrontation with Bruno, the leader of her captors. His hesitations about their actions force him to reevaluate their mission, leading to a crisis that tests Séverine’s resolve.

Despite the chaotic environment and the personal toll of her captivity, Séverine maintains her dignity and a clear sense of self. Throughout her ordeal, she remains determined to escape and reclaim her life, even as she is forced to confront the complexities of her situation, her family, and her own identity.

Eventually, Séverine’s prolonged captivity forces her to come to terms with the realities of her privileged life, her desires for fame, and the harshness of the political struggle surrounding her. The independence movement that led to her kidnapping is filled with contradictions and moral gray areas.

Despite her growing understanding of the cause, Séverine realizes that true freedom may come at a much greater personal cost than she originally imagined. The experiences she endures force her to reassess not just her political beliefs but also her place in the world and the nature of her own identity.

As the story reaches its conclusion, Séverine emerges as a changed person, having survived the ordeal and gained a deeper understanding of the forces that shaped her world. While she escapes the physical confinement of her captors, she cannot fully escape the psychological and emotional scars of her experience.

Her time in captivity has transformed her, challenging her ambitions and forcing her to navigate the intersection of political ideologies, personal desires, and family dynamics. The Bombshell explores themes of power, resistance, identity, and the personal cost of political conflict, all through the lens of Séverine’s journey of self-discovery and survival.

Characters

Séverine Guimard

Séverine Guimard is a complex and multifaceted character whose journey from a disillusioned teenager to a revolutionary figure lies at the heart of The Bombshell. At the story’s outset, she is portrayed as a sophisticated yet somewhat detached seventeen-year-old, caught in the tension between her ambitions and the expectations placed on her by her influential father.

Raised in Corsica, she feels out of place in the provincial island life and yearns for a more glamorous existence, often fantasizing about the lights of Paris or Hollywood. Despite her sharp features and her father’s political stature, Séverine struggles with feelings of inadequacy and isolation, especially in relation to her mother, an American poet whose intellectualism she admires but feels distant from.

As the narrative progresses, Séverine’s character evolves from a privileged, manipulative young woman into someone forced to confront her own powerlessness during her kidnapping by a group of Corsican separatists. The experience brings a deep transformation in her, forcing her to grapple with her own identity, her desires, and the stark realities of political struggle.

Her captivity leads to moments of profound self-reflection as she realizes the complexities of her position within both her family and society. Through her manipulation of her captors, particularly Bruno, Séverine learns to navigate the chaotic world around her while simultaneously becoming more aware of the contradictions and moral ambiguities inherent in her captors’ cause.

By the story’s end, Séverine’s evolution is marked by a more nuanced understanding of power, survival, and personal agency, as she moves beyond her previous self-centered ambitions to become a more introspective and politically conscious individual.

Bruno

Bruno, one of Séverine’s captors, stands as a conflicted character who serves as both a source of tension and intellectual stimulation for Séverine. As a passionate advocate for Corsican independence, he embodies the ideals of revolution, yet his internal struggle creates a sense of unpredictability.

Initially, Bruno presents himself as a hardened militant, fully dedicated to the cause of Corsican freedom. However, his relationship with Séverine forces him to confront his own doubts about the violence and radical actions the movement endorses.

He is not merely a one-dimensional revolutionary; instead, he reveals moments of hesitation, self-reflection, and an underlying vulnerability, especially in his interactions with Séverine.

Their relationship is complicated, marked by intellectual debates about colonialism, revolution, and the moral implications of violence. As Séverine becomes more involved in the movement, her ideological and emotional connection with Bruno deepens, yet it is also fraught with complications.

Bruno’s uncertainty about the movement’s methods and his fluctuating feelings toward Séverine create a volatile dynamic, especially as they both struggle to reconcile their personal desires with their political commitments. By the end of the story, Bruno’s character remains in a state of internal conflict, torn between his revolutionary zeal and the personal connections that complicate his mission.

His role as a captor evolves into a more complex portrayal of the human cost of revolutionary ideals.

Tittu

Tittu, another member of the separatist group, is one of Séverine’s captors with whom she forms an unexpected bond. Unlike Bruno, Tittu is less politically committed and more emotionally vulnerable, which makes him more relatable to Séverine.

Over the course of her captivity, Séverine begins to see beyond his role as a militant and starts to understand his personal struggles. Their relationship grows from mutual suspicion to a form of understanding, culminating in a brief romantic encounter.

Despite his involvement in the political violence of the separatist group, Tittu’s character is portrayed as being more conflicted and less certain about the righteousness of the cause than others in the group. This inner turmoil makes him a more humanized character, one whose vulnerabilities contrast with the ideological rigidity of some of the other militants.

Tittu’s involvement in the political struggle becomes increasingly difficult to navigate for both him and Séverine, especially as their emotional and personal boundaries become entangled with the larger political movements around them.

Petru

Petru, another member of the separatist group, is more distant and hostile compared to the others. He represents a more traditional, perhaps hardened, figure within the group—someone who views Séverine’s presence as a distraction from the cause.

Petru’s skepticism about Séverine’s motivations and her true commitment to the independence movement underscores a larger theme of ideological purity versus personal desires. He remains suspicious of her, especially as her increasing emotional attachment to the group challenges his belief in the purity of their cause.

Petru’s character is marked by a strong sense of duty to the Corsican independence movement, but this sense of duty often leaves little room for empathy or understanding of Séverine’s transformation. His complex, sometimes antagonistic relationship with her highlights the tensions between personal sacrifice and the broader ideological struggle.

Despite his resistance to Séverine’s involvement, Petru’s character offers an essential contrast to the more malleable or emotionally complex figures like Bruno and Tittu.

Ramona

Ramona, a key character in the later part of the narrative, is the mother of Petra and a woman with a secret past that ties her to the radical days of the Corsican nationalist movement. In her quiet, hidden life, Ramona seeks to reconcile the woman she was with the person she has become.

Her past, embodied in the figure of Séverine Guimard, is something she wishes to keep buried, especially as her daughter, Petra, grows curious about the truth. Ramona’s character is defined by her struggle to maintain the facade of normalcy, while secretly carrying the weight of her violent, revolutionary past.

When forced to confront her history, Ramona’s inner conflict becomes palpable, as she navigates the guilt, regret, and unresolved emotions tied to her involvement in the political violence of her youth. Her reunion with Bruno, and the subsequent revelations to her daughter Petra, reveal a deeply human character torn between past loyalties and the responsibilities of motherhood.

Ramona’s journey is ultimately one of self-reflection, guilt, and the challenge of reconciling past actions with present desires.

Petra

Petra, Ramona’s daughter, plays a pivotal role in unearthing the secrets of her mother’s past. Initially innocent and unaware, Petra’s curiosity leads her to uncover the truth about her mother’s former life as Séverine Guimard.

As she pieces together the fragments of Ramona’s past, Petra evolves from a passive observer to an active participant in the unraveling of her family’s history. Her growing awareness of the Corsican nationalist movement, and the realization that her own father was involved in the political violence, forces Petra to confront complex questions about identity, heritage, and morality.

Petra’s role is crucial in linking the past with the present, offering a fresh perspective on the political struggles that shaped her mother’s life. Her ability to empathize with Ramona, even after learning the truth, illustrates the depth of her emotional maturity and understanding, despite the weight of her mother’s confessions.

Themes

Political Ideology and Revolution

In The Bombshell, the theme of political ideology and revolution plays a central role in shaping the characters’ actions and personal journeys. Séverine, initially an indifferent teenager, becomes deeply entangled in the ideological struggles surrounding Corsican independence.

Her involvement begins with an intellectual curiosity, fueled by her encounters with radical literature and the persuasive arguments of Bruno, one of her captors. Over time, Séverine’s transformation into a revolutionary figure reflects her growing understanding of the deeper social and political forces at play in Corsica.

Her ideological evolution is not just about adopting a cause but involves an internal conflict between her desire for personal recognition and her emerging commitment to the political movement. Séverine’s journey through captivity exposes her to the harsh realities of the Corsican separatist cause, where the ideals of self-determination and resistance to oppression are juxtaposed with the violence and moral contradictions inherent in the group’s actions.

Her shifting perspective underscores the complex nature of political movements—while she initially questions the use of violence, she later finds herself complicit in acts that challenge her own moral compass. This theme also highlights the tension between idealism and practicality, as Séverine is forced to confront the consequences of her actions, not just for herself, but for those around her.

The story suggests that revolutions, while often born from noble intentions, carry a heavy cost, one that affects both the individual and the collective.

Identity and Self-Discovery

The journey of self-discovery is a pervasive theme in The Bombshell, particularly through Séverine’s personal evolution. Initially portrayed as a disillusioned teenager, Séverine is deeply dissatisfied with her life in Corsica and yearns for something greater, a desire for fame and recognition that drives her to pursue a career in acting.

However, her kidnapping and subsequent captivity force her to confront aspects of her identity she has long ignored or taken for granted. Throughout the ordeal, Séverine is stripped of her physical and social trappings, leaving her to grapple with her innermost fears, desires, and vulnerabilities.

In this environment, she is forced to reevaluate her position in both her family and society, especially as she begins to understand her role as a political pawn. The confinement and manipulation she experiences compel her to examine her past and her relationships with her parents, particularly her father, whose political ambitions she resents, and her mother, who represents an intellectualism that feels disconnected from her own ambitions.

As Séverine bonds with her captors, particularly Bruno, the intellectual debates they have and her growing empathy for their cause further complicate her sense of self. By the end of the story, Séverine’s evolution is marked by a more profound understanding of who she is—no longer just a victim, but someone who can shape her own narrative, even in the face of overwhelming adversity.

Her journey is a poignant exploration of how identity is shaped by personal experiences, choices, and the societal forces that one cannot easily escape.

Power Dynamics and Manipulation

The theme of power dynamics and manipulation is intricately woven throughout The Bombshell, particularly in the context of Séverine’s captivity and her relationship with her captors. Initially, Séverine sees herself as a powerless victim, held by a group of amateurs with seemingly no clear plan or leadership.

However, as the days pass, she begins to understand that power is not solely determined by physical control but also by the ability to influence others emotionally and psychologically. Her physical allure, which she had always used to manipulate boys like Antoine, becomes a tool she uses to exert control over the men who hold her captive.

Séverine manipulates Bruno and the others, using her charm and intelligence to sow discord and challenge their authority. In doing so, she demonstrates an evolving understanding of power—she realizes that, even in a position of vulnerability, she can assert control by playing on the weaknesses and doubts of those around her.

This dynamic also plays out in her relationship with the separatist cause itself. Initially, she is an outsider, observing the group from a distance, but as her captivity drags on, she becomes an active participant in the ideological struggle, even as she wrestles with the contradictions and moral complexities of their actions.

The manipulative power Séverine holds over her captors and her ability to turn the situation in her favor are symbolic of the broader theme of how power shifts and operates in relationships, both personal and political.

Family and Relationships

Family and the complexity of relationships are key themes in The Bombshell, explored through Séverine’s interactions with her parents and her evolving connections with her captors. Her strained relationship with her father, Paul Guimard, is central to her internal conflict throughout the story.

Though she resents him for taking the family to Corsica, she also recognizes his political power, which she both admires and wishes to escape. This ambivalence toward her father mirrors her emotional disconnection from her mother, whose intellectualism feels disconnected from Séverine’s own desires.

The tension between these familial bonds plays a significant role in shaping Séverine’s identity, particularly her longing for approval and her desire to distance herself from the conventional life her parents represent. As Séverine is held captive, she also begins to develop complex relationships with her captors, particularly Bruno and Tittu.

These relationships evolve from initial distrust and animosity to a more nuanced understanding of the individuals involved. The emotional connections she forms with them are marked by tension and contradiction—while she recognizes their ideological commitment, she also sees their vulnerabilities and internal conflicts.

This complexity deepens as Séverine navigates her desire for freedom, her feelings for Bruno, and her growing understanding of the political and personal forces at play. Ultimately, the story emphasizes that family and relationships are not simply defined by blood or societal expectations but are shaped by emotional intimacy, ideological alignment, and the personal choices that each individual makes.

Guilt and Consequences

A prominent theme in The Bombshell is the exploration of guilt and the consequences of one’s actions. Séverine’s involvement in the political struggle for Corsican independence brings with it a series of unintended outcomes that weigh heavily on her conscience.

As she becomes more deeply entrenched in the separatist cause, she begins to confront the personal costs of her revolutionary actions. Her decision to join the militants and engage in violent acts causes a rift with her family, and she is left to grapple with the repercussions of her choices.

The guilt she feels is compounded by the loss of innocence she experiences during her captivity. She realizes that the ideals she once admired in the revolutionaries are not always as pure or idealistic as she had imagined.

The actions of her captors, including their internal divisions and the violence they condone, force Séverine to confront the consequences of her own participation in a cause that is fraught with moral ambiguities. This theme is further developed as Séverine becomes aware of the wider implications of her political involvement, such as the effect her actions have on her father’s career and the broader political situation in Corsica.

Her internal conflict grows as she weighs the desire for personal freedom against the cost of her ideological commitment, ultimately questioning whether the sacrifice of her own morality and personal relationships is worth the larger goal of independence. The story suggests that while the pursuit of political ideals can be noble, it often comes with a heavy price—one that leaves characters like Séverine to reckon with their guilt and the lasting consequences of their decisions.