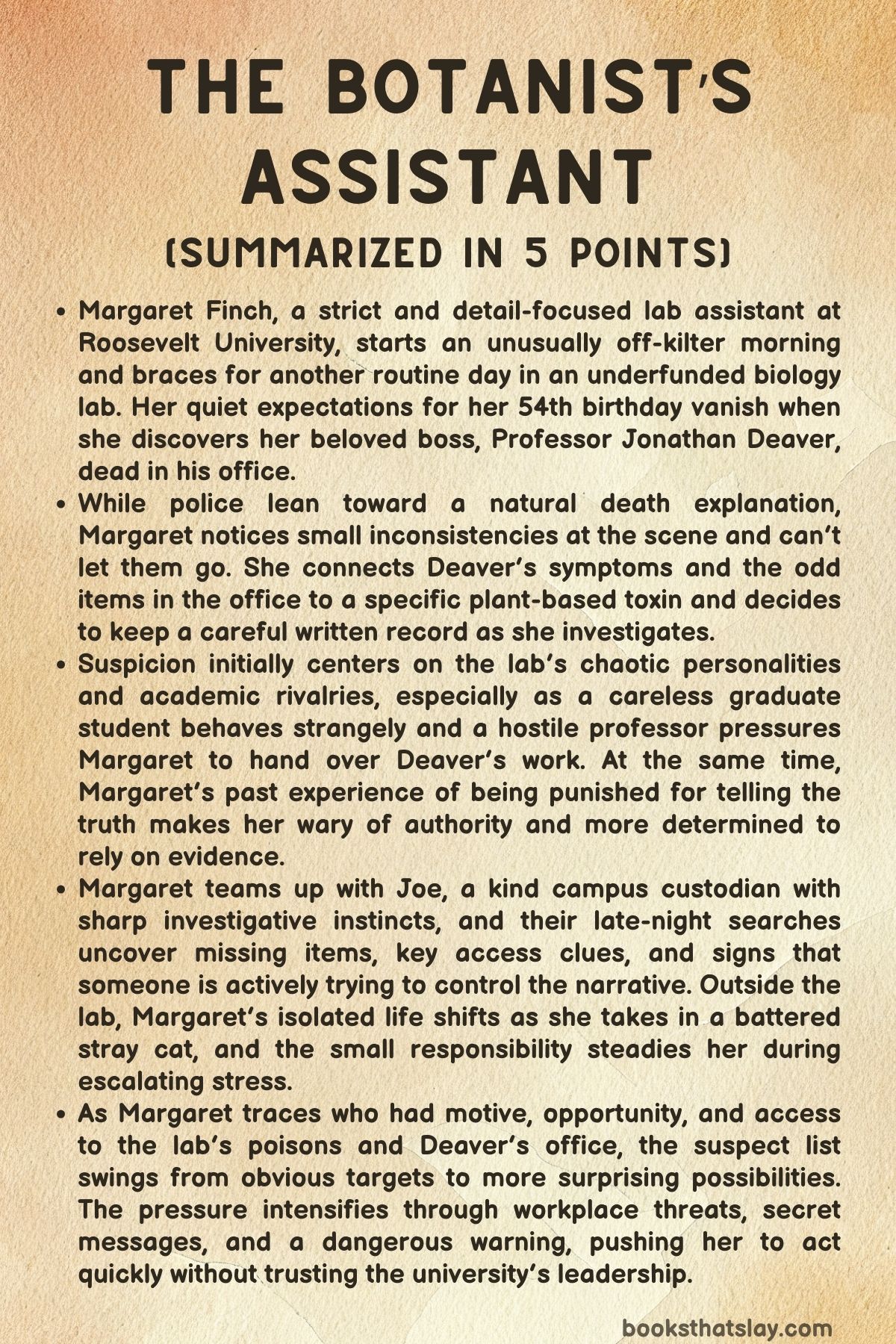

The Botanist’s Assistant Summary, Characters and Themes

The Botanist’s Assistant by Peggy Townsend is a campus mystery set inside a biology lab where ambition, ego, and quiet devotion collide. Margaret Finch is a veteran lab assistant who runs experiments the way she runs her life: measured, tidy, and controlled.

She prefers facts to feelings, routines to surprises, and plants to people. Then her brilliant boss dies in his office on the eve of her birthday, and the official explanation doesn’t match what Margaret saw. With the lab’s future up for grabs and powerful colleagues circling, she starts using the one thing she trusts—careful observation—to find out what really happened.

Summary

Margaret Finch arrives at Roosevelt University’s biology lab five minutes late, and the tiny slip unsettles her more than she wants to admit. Her days are built on precision: the same commute, the same order of tasks, the same silent pride in keeping a neglected lab functioning.

She is turning fifty-four tomorrow, and she expects it to pass without notice, especially after a blunt comment that has kept her colleagues at arm’s length.

In the lab, Margaret works around outdated equipment and a sluggish computer while managing the human chaos around her. Calvin Hollowell, a postdoc, shows up coughing and anxious, overflowing with complaints and fears.

Travis Zhang, a graduate student known for accidents and carelessness, arrives late and clumsy as usual. A humanities intern, Emily Frost, trails behind him, observing scientists for a writing project.

Their supervisor, Professor Jonathan Deaver, bursts in with relentless energy and optimism. Margaret admires Deaver fiercely.

He gave her a second chance in science when no one else would, and she pours herself into his research: a rainforest plant that causes intense pain but may also suppress tumor growth.

The next day—Margaret’s birthday—turns into something she never imagined. After a tense commute and another Zhang mishap that scatters chemicals, she goes to Deaver’s office to ask about a misdelivered shipment.

Inside, she finds him dead on the floor beside his desk, bloodied and unnaturally still. Shock locks her body for a moment before she checks for a pulse.

Others rush in. Calvin calls 911; Beth Purdy, the dean’s assistant, screams.

A police officer, Bianchi, arrives and quickly leans toward a natural-death narrative, especially when Calvin blurts out that Deaver had a genetic heart condition and avoided doctors.

Margaret’s grief comes out as inventory. She notices details that don’t sit right: a photo knocked down, windows open, a Diet Coke bottle Deaver never drank, a missing glass, and an empty scotch bottle.

She also remembers Deaver’s pupils looking oddly wide. When the body is removed and the lab is left hollow, she stays late washing neglected glassware until she nearly collapses.

A night custodian named Joe finds her, offers tea and cookies, and listens without pushing. His steady presence gives her enough balance to go home.

By morning, Margaret’s observations have turned into a theory. Deaver’s symptoms and the strange drink setup suggest poisoning—specifically atropine, associated with deadly nightshade.

She calls Officer Bianchi, laying out the science, but he brushes her off and repeats the heart-condition explanation. Margaret has been punished before for telling inconvenient truths, and the dismissal triggers an old warning in her head: if she wants answers, she may have to get them herself.

She begins documenting everything in a notebook, the way she has since a long-ago family tragedy trained her to rely on written facts. At a memorial meeting, the dean praises Deaver as a “warrior of science,” then announces his death formally.

Zhang suddenly laughs and bolts from the room, an alarming reaction that pushes Margaret to look into him first. She checks his social media and finds a post that reads like a threat.

Still, suspicion alone isn’t proof, and she needs evidence.

One night she sneaks into the science building to test for traces of carbon-14, hoping to identify who handled materials around the time of death. The lab is contaminated with traces in many places, including Zhang’s cup, and Margaret feels a surge of triumph—then panic.

She knows she should preserve the scene, but her reflex for cleanliness takes over. She cleans most of the residue, leaving only a couple of key spots untouched, and tells herself she has protected both science and justice, even as she fears she may have sabotaged her own case.

The pressure increases when Dr. Levi Blackstone, a vain and aggressive professor, appears and claims Deaver stole his idea about the medically valuable poisonous plant. Blackstone threatens Margaret’s job and hints he will take over the lab with the dean’s support.

Margaret’s fear isn’t just professional. Years earlier, she reported falsified research results by a supervisor and was punished for it—pushed out of academia and branded unreliable.

Deaver was the one who later recognized her competence and brought her back. Losing the lab now would feel like losing him all over again.

Margaret tries to figure out who had access to Deaver’s office and the locked poison cabinet. She tricks Beth Purdy into sharing useful information, then recruits Joe to help her break into the office after hours.

Inside, she finds the Diet Coke bottle and the scotch glass have vanished, as if someone cleaned up deliberately. Joe finds a navy-blue button and an envelope addressed to Margaret: a birthday card from Deaver.

The small kindness breaks through her composure and strengthens her resolve. Margaret takes samples, searches for Deaver’s notebooks to establish the origin of the research, and confirms Zhang touched the doorknob—evidence he entered, but not proof he killed.

As Margaret follows leads, her suspect list grows. She spies on Blackstone’s wealthy neighborhood and learns of recent money troubles and a sudden payoff of HOA fees, then sees him as a playful father and briefly doubts her conclusions.

She visits Veronica Ann Deaver, the widow, and discovers a garden packed with poisonous plants and a home wired with surveillance cameras. Veronica Ann is openly hostile, admits she resented Jon’s refusal to credit her ideas, and says she is glad he is dead.

Margaret also meets Dr. Rachel Sterling, a young biochemist who tearfully reveals she had been Deaver’s lover and believed he planned to leave his wife. Sterling shares another crucial detail: Deaver received a threatening text shortly before he died.

Meanwhile, Margaret’s personal life shifts in quieter ways. A battered tomcat appears on her porch as if delivered by the same darkness that has started stalking her home.

She tries to keep her distance, then lets him inside during a cold rain and names him Tom. The cat’s stubborn survival mirrors Margaret’s own determination to stay standing.

Back at the university, Beth Purdy grows nervous and begins helping Margaret in secret, slipping notes about who holds master keys. Calvin, pressured by the dean and Blackstone, nearly signs a statement blaming Margaret for safety violations.

Margaret blocks Calvin from illegal schemes to obtain rare plant material and tries to keep the research alive while her job teeters. Then Purdy leaves Margaret a cupcake “for her birthday.” Something about it feels wrong, and Margaret doesn’t eat it.

The investigation snaps into focus when Margaret and Joe enter Deaver’s office again and find Purdy already there—with the missing notebook and access to the poison cabinet. Cornered, Purdy confesses she had an affair with Deaver and poisoned him with atropine after he ended it.

She boasts that she watched him die and assumes no one can prove it. Joe reveals he recorded her confession.

In a final, chilling admission, Purdy says the cupcake was poisoned too—meant for Margaret.

Margaret realizes Calvin ate the cupcake. She races to find him, and he survives after emergency treatment.

Tests show the cupcake contained wolfsbane. Purdy is arrested and charged, and the case becomes impossible for the university to bury.

Joe, a former investigative journalist, writes an exposé that exposes the institution’s attempted cover-up and the scramble for Deaver’s work.

Months later, Margaret’s world is steadier, though permanently changed. Calvin recovers.

Tom remains part of her life. The lab continues under new leadership, funding arrives, and Margaret is reinstated.

In her garden, over a shared meal with Joe and Calvin, she finally has something she rarely allowed herself before: not just order, but company—earned through truth, persistence, and the refusal to look away.

Characters

Margaret Finch

Margaret Finch stands as the intellectual and emotional core of The Botanist’s Assistant. She is a woman defined by discipline, precision, and an almost monastic devotion to order—both in her work as a laboratory assistant and in her personal life.

Her world revolves around structure: every minute accounted for, every beaker and petri dish in its place. Beneath this rigor lies a woman scarred by past betrayal and professional exile, whose faith in science serves as both shield and identity.

Margaret’s obsession with detail, initially perceived as a quirk, becomes her weapon when her mentor, Dr. Deaver, dies under mysterious circumstances. Her transformation—from a loyal assistant bound by institutional obedience to a tenacious investigator defying authority—reveals her quiet heroism.

The narrative charts her evolution from rigid precision to moral courage, as she reclaims agency through intellect and persistence. Yet, Townsend never romanticizes her: Margaret remains deeply human, prone to loneliness, doubt, and emotional repression.

Her bond with Joe, the custodian, and even her compassion for the scarred tomcat reflect her latent yearning for connection amid isolation. By the novel’s end, she emerges not merely as a detective of scientific truth but as a woman rediscovering empathy and resilience in a world that once silenced her.

Dr. Jonathan Deaver

Dr. Jonathan Deaver is the charismatic and flawed professor whose death catalyzes the events of The Botanist’s Assistant. To Margaret, he is more than a mentor—he is a redeemer who resurrected her scientific career after years of disgrace.

Deaver’s brilliance and enthusiasm make him a magnetic leader, but his charm conceals personal chaos. He thrives on admiration, particularly from his subordinates, and his energy masks emotional volatility.

His research into a rainforest plant’s pain-inducing compound represents both ambition and moral ambiguity—a metaphor for scientific pursuit tinged with danger. Deaver’s relationships, particularly with women such as Margaret, Beth Purdy, and Rachel Sterling, expose his emotional recklessness and the web of jealousy surrounding him.

His sudden death transforms him into a paradox: part martyr of science, part flawed human undone by his appetites. Through Margaret’s investigation, Deaver is reframed not just as a victim of poisoning but as the embodiment of the fragile boundary between genius and self-destruction.

Calvin Hollowell

Calvin Hollowell, the anxious postdoctoral researcher, mirrors the disillusionment and vulnerability of modern academia. Neurotic, chain-smoking, and perpetually self-doubting, Calvin functions as Margaret’s foil.

Where she is disciplined, he is chaotic; where she represses emotion, he bleeds anxiety. His dependence on external validation and his sense of professional failure make him both pitiable and endearing.

Yet beneath his nervous chatter lies loyalty and moral integrity—traits that ultimately surface when he stands by Margaret after Dr. Deaver’s death. His survival after eating the poisoned cupcake completes a symbolic arc: he begins the novel as an embodiment of decay and ends it as a fragile survivor of the toxic environment—both literal and institutional—that the university represents.

Travis Zhang

Travis Zhang, the clumsy graduate student, serves as both comic relief and a red herring in The Botanist’s Assistant. His repeated lab accidents, social ineptitude, and misplaced confidence make him the initial suspect in Deaver’s death.

However, Townsend uses Zhang to critique the academic hierarchy’s tendency to scapegoat the inexperienced. Beneath his bumbling exterior is a young man suffocated by parental expectations and institutional condescension.

When he leaves to start a cannabis-chocolate business, his exit represents liberation from academia’s hypocrisy—a small act of rebellion that contrasts Margaret’s entrapment. Zhang’s innocence ultimately highlights the destructive competitiveness of the scientific world rather than malice within him.

Dr. Levi Blackstone

Dr. Levi Blackstone embodies vanity and intellectual theft—a rival academic whose arrogance and moral bankruptcy contrast sharply with Margaret’s integrity. His arrival, marked by disrespect for order and hierarchy, signals the institutional rot beneath the university’s polished exterior.

Blackstone’s history of lawsuits and ethical misconduct reveals a man driven not by discovery but by ego. His pursuit of Deaver’s research and his manipulation of authority figures such as the dean expose how power, not truth, often governs scientific institutions.

Through Blackstone, Townsend dissects the toxic masculinity and corruption that plague competitive research environments. He is not the murderer but remains complicit in the moral decay that allows such crimes to fester.

Beth Purdy

Beth Purdy, the dean’s assistant, initially appears as a peripheral, somewhat timid figure—helpful, gossip-prone, and eager to please. However, her transformation into the story’s true antagonist reveals Townsend’s mastery of psychological deceit.

Purdy’s affair with Dr. Deaver and her subsequent act of poisoning him stem from humiliation and rage—the emotions of a woman overlooked and dismissed in a patriarchal system. Her manipulation of institutional bureaucracy to conceal her crime underscores her cunning.

Yet, her downfall—poisoning Calvin by mistake—reveals the tragic futility of her vengeance. Through Purdy, the novel examines how invisibility and resentment can ferment into madness when combined with systemic sexism and emotional neglect.

Veronica Ann Deaver

Veronica Ann Deaver, the professor’s estranged wife, is a complex figure of pride, bitterness, and intellect. Her “poison garden” literalizes her personality: beautiful yet deadly, cultivated yet vengeful.

She is neither innocent widow nor outright villain; rather, she represents the long-silenced spouse who feels erased by her husband’s fame. Her claims of intellectual contribution to Deaver’s work blur the boundary between inspiration and ownership.

Her manipulation of Margaret reveals a sharp intelligence masked by domestic elegance. Veronica is a study in resentment transformed into agency—a woman who weaponizes charm and ambiguity to survive in a world that rewards male ambition while dismissing female intellect.

Dr. Rachel Sterling

Rachel Sterling is introduced as a poised biochemistry professor and, later, as Dr. Deaver’s lover. Her initial composure masks deep emotional fragility, intensified by betrayal and loss.

Through Sterling, Townsend explores the intersection of gender, science, and vulnerability. Her relationship with Deaver blurs the professional and personal, exposing the risks faced by women navigating male-dominated institutions.

Unlike Purdy, Sterling channels grief into confession and truth, providing Margaret with crucial insight rather than deception. Her father’s position as the head of Phoenix Pharmaceuticals adds moral complexity—tying personal ambition to corporate power.

Sterling’s honesty and pain contrast sharply with Purdy’s venom, positioning her as a mirror to what Margaret might have become under different circumstances.

Joe Torres

Joe Torres, the scarred janitor and former investigative journalist, is the novel’s moral compass and emotional anchor. His quiet empathy, patience, and integrity counterbalance the chaos of Margaret’s world.

A survivor of violence and disillusionment, Joe symbolizes redemption through kindness. His relationship with Margaret—built on mutual respect and intellectual curiosity—offers her the human connection she has long denied herself.

Joe’s guidance and eventual exposure of institutional corruption restore both justice and dignity to Deaver’s death. He represents the idea that truth is not the sole province of scientists but of all who seek it with courage and compassion.

Tom the Cat

Though non-human, Tom serves as one of the most poignant symbols in The Botanist’s Assistant. A battered, one-eyed stray, he mirrors Margaret’s own wounded resilience.

His arrival at her doorstep marks a turning point: the intrusion of life and unpredictability into her sterile, ordered world. Tom’s gradual acceptance into her home parallels her reawakening capacity for affection and trust.

He is a living reminder that healing often comes not through control but through vulnerability. By the novel’s conclusion, Tom’s presence underscores the theme of survival—both his and Margaret’s—in a world defined by cruelty, decay, and unexpected grace.

Themes

Order, Control, and the Fear of Disorder

Margaret Finch’s life is built on precision, not because she likes neatness as a preference, but because order functions as her main defense against uncertainty. A five-minute delay in her morning routine unsettles her as if time itself has betrayed her, and that small fracture becomes a signal that something larger is slipping beyond her ability to manage.

Throughout The Botanist’s Assistant, her attention repeatedly returns to misplaced objects, messy benches, badly parked cars, and contaminated workspaces, but those details carry emotional weight: disorder reads to her as danger, exposure, and loss of authority. This theme becomes sharper after Deaver’s death, when her grief expresses itself through procedures—checking observations, listing anomalies, and organizing evidence—because naming and measuring are the only forms of control she trusts.

Even her decision to investigate poisoning is driven by a desire to restore logic to a scene that others are quickly reducing to a convenient explanation. The most revealing moment is when she finds radioactive residue and feels pulled in opposite directions: preserve the evidence or clean it.

She chooses cleanliness even while telling herself she is serving justice, showing how deep her compulsion runs. Control helps her function and survive, yet it also threatens to distort her judgment, making her mistake “tidying” for solving.

The theme does not present order as purely admirable or purely harmful; it shows how a controlling routine can be both a stabilizing framework and a trap that prevents a person from sitting with ambiguity. As the story progresses, Margaret’s growth is measured by her ability to tolerate mess—physical, emotional, and moral—without trying to erase it immediately.

Grief Without Comfort and the Search for Truth

Grief in The Botanist’s Assistant is not presented as soft, communal mourning but as something lonely, practical, and resistant to performance. Margaret does not receive the kind of social support that makes loss feel shared; her bluntness has already left her isolated, and Deaver’s death removes the one relationship that anchored her professional identity and daily rhythm.

Instead of tears and speeches, her grief appears as fatigue, insomnia, and an urge to keep working because stopping would force her to feel the void. She scrubs glassware late at night in a bloodstained coat, not because the lab needs it urgently, but because cleaning becomes a way to translate shock into action.

Her memories of an earlier personal tragedy—hinted through her long habit of keeping notebooks—explain why she treats catastrophe as a problem to document rather than an experience to surrender to. This is why she notices details that others dismiss: the dilated pupils, the unfamiliar Diet Coke, the missing glass, the open window.

The investigation is not only about justice for Deaver; it is Margaret’s attempt to make the loss “make sense” so her world can stop feeling random and unsafe. The theme also highlights how institutions manage grief by simplifying it.

The memorial meeting frames Deaver as a heroic figure and turns his death into a story of sacrifice, while Margaret sees the unanswered questions and the possible manipulation behind quick conclusions. Her refusal to accept the heart-condition narrative is partly scientific reasoning, but it is also grief refusing to be packaged.

The emotional payoff arrives when she finds the birthday card: in a single object, Deaver becomes real again—human, playful, attentive—and Margaret’s grief breaks through her controlled exterior. The theme suggests that truth-seeking can be a form of mourning when traditional comfort is unavailable: she cannot bring him back, but she can refuse to let his ending be falsified or ignored.

Power, Reputation, and Institutional Self-Protection

The university setting in The Botanist’s Assistant exposes how power often works through image management rather than direct confrontation. After Deaver’s death, the system’s first instinct is not curiosity but closure.

Officer Bianchi leans toward the easiest explanation, the dean treats Margaret’s poisoning theory as an embarrassment, and decisions about the lab’s future are made with career optics in mind. The story repeatedly shows that authority prefers narratives that reduce risk: a natural death is simpler than a murder, a “hysterical” assistant is easier to silence than a whistle-blower with inconvenient evidence, and a transfer of leadership to a confident professor is more acceptable than letting a meticulous lab assistant challenge the hierarchy.

Blackstone embodies a particular kind of academic power: status, entitlement, and the belief that credit matters more than integrity. He threatens Margaret’s job not by proving she is wrong, but by implying she is replaceable, demonstrating how vulnerable technical workers can be when titles and networks decide who is heard.

The theme becomes even darker through Beth Purdy’s role, because it reveals that institutional control is not only top-down. A secretary, positioned near access and information, can manipulate gates, keys, and messages while appearing harmless.

The university’s attempt to hand over Deaver’s work and attach new names to grants shows how easily research can be treated as property to be reassigned, especially when the person who generated the work is no longer alive to defend it. Margaret’s earlier career trauma—being punished for reporting falsified results—reinforces that the institution’s priority is often protecting itself, not protecting truth.

When the story culminates in exposure and public attention, the shift is not portrayed as the institution suddenly becoming ethical; it is portrayed as the institution being forced into accountability. The theme argues that professional environments can reward silence and punish inconvenient honesty, and that the fight for truth is also a fight against systems designed to minimize scandal.

Loyalty, Recognition, and the Fragile Bond Between Mentors and Workers

Margaret’s devotion to Deaver is central to how she navigates both her job and her identity. She works tirelessly for him, admires his energy, and believes in the research mission, yet her loyalty is not matched by security or recognition.

This imbalance is important: she is not simply grieving a boss; she is grieving the one person who restored her place in science after her reputation was ruined. The flashback to her earlier whistle-blowing experience explains why loyalty becomes so intense in her relationship with Deaver.

He gave her dignity when an earlier supervisor took it away, and that generosity turns into a kind of debt she feels she must repay through endless competence. In that way, loyalty is not only affection; it is survival.

After his death, her loyalty transforms into guardianship of his legacy—protecting the lab, defending his integrity against Blackstone’s accusations, and fighting against administrative takeover. Yet the theme also shows how loyalty can be exploited.

Blackstone demands allegiance as a condition of employment, implying that ethics should follow power rather than truth. The dean expects compliance, not questions.

Even Calvin is pressured to sign statements that shift blame onto Margaret. In contrast, Deaver’s birthday card and the evidence of his intention to bring Margaret along to a new opportunity show a more mutual form of loyalty: he did not only benefit from her labor; he valued her.

That mutuality is what makes her grief sharper and her resolve stronger. The theme also explores recognition as something withheld from the people doing foundational work.

Margaret is essential to the lab’s functioning, yet her position is precarious, her ideas are dismissed, and her warnings are treated as emotional instability. By the end, the story does not pretend recognition fixes everything, but it does show that respect and support change what a person can endure.

Loyalty becomes healthiest when it is met with responsibility and fairness, rather than demanded as obedience.

Women, Credibility, and the Politics of Being Believed

Margaret’s experiences highlight how quickly a woman’s certainty can be framed as irrational, especially when she challenges powerful men or institutional convenience. When she reports poisoning suspicion, the response is not a serious scientific review of the evidence but a dismissal that labels her “hysterical,” turning a technical claim into an emotional stereotype.

This theme is reinforced by her professional history: when she previously reported falsified results, she was punished and pushed out, showing a pattern where speaking up costs more than staying quiet. The story also contrasts different models of femininity and credibility.

Rachel Sterling is young, polished, and professionally respected, yet even she is emotionally reduced to “the lover” once her relationship is revealed, as if intimacy undermines her authority. Veronica Ann is treated as a widow, but her competence and influence emerge through her knowledge, her connections, and her strategic bargaining.

Beth Purdy uses the expectation that she is merely an assistant to move unseen, weaponizing invisibility as power. Margaret, meanwhile, is blunt, older, and socially awkward—traits that make people less inclined to view her as a reliable narrator, even when her observations are accurate.

Her struggle is not only to solve a crime; it is to be treated as someone whose analysis deserves attention. The theme shows how professional credibility is shaped by social performance: who sounds calm, who seems “reasonable,” who fits the image of a scientist versus the image of a difficult employee.

Margaret’s meticulous notebooking becomes both a personal anchor and a strategy against disbelief, because documentation is the only language she trusts others might accept. By emphasizing the repeated refusals she encounters, the story exposes a social reality: truth can be present in plain sight, but belief is filtered through bias, hierarchy, and comfort.

Margaret’s eventual vindication is not portrayed as a triumph of persuasion; it is a triumph of evidence finally becoming impossible to ignore.

Ethics in Science and the Thin Line Between Discovery and Harm

The scientific work in The Botanist’s Assistant is not a neutral backdrop; it is a source of both hope and threat. The lab studies a rainforest plant compound that causes pain and might suppress tumors, which means the same object can represent healing or suffering depending on use and intent.

That duality becomes literal when poisoning enters the plot: atropine, wolfsbane, belladonna—plants and chemicals that can be studied, stored, and handled in professional settings become tools for murder when ethics collapse. The theme asks what it means to work every day with substances that can kill, and how easily “safety protocols” can become either protection or weapon.

Margaret’s careful procedures show a respect for the dangers of research, while Zhang’s accidents and contamination highlight how incompetence or carelessness can create real risk. The ethical tension intensifies when Calvin suggests acquiring seeds through illegal channels, showing how desperation and ambition can push researchers toward wrongdoing even when they believe the goal is worthwhile.

The conflict around stolen ideas and grant credit adds another ethical layer: scientific discovery is treated as currency, and the pressure to publish and profit creates incentives to lie, steal, and sabotage. Deaver’s potential move to Phoenix Pharmaceuticals introduces the corporate dimension—research as a pathway to wealth and status—which increases the stakes around ownership.

The theme does not argue that science is corrupt by nature; it argues that science becomes vulnerable when human incentives overpower safety and integrity. Margaret represents a form of ethics grounded in method: careful handling, accurate records, and refusal to cut corners.

Beth Purdy represents the opposite: access to scientific tools without scientific restraint, using lab knowledge as a means of control and revenge. By the end, the story suggests that scientific environments require more than intelligence; they require structures that prevent access from becoming abuse and ambition from becoming harm.

Isolation, Chosen Family, and Unexpected Care

Margaret’s home life is defined by solitude, routine, and the belief that she is best off relying only on herself. Her garden is her sanctuary because it follows rules she can maintain: plants respond to care, seasons repeat, and growth is predictable enough to feel safe.

Yet the story steadily challenges her isolation by introducing care that arrives from unexpected places. Joe, the janitor, offers her tea and cookies when she is in shock, and he listens without trying to control her narrative.

His kindness is practical and steady, the opposite of institutional responses that minimize her concerns. As their relationship deepens and his background as an investigative journalist is revealed, he becomes both emotional support and a partner in truth-seeking.

The presence of Tom the cat works similarly. Margaret insists she will not keep him, yet she feeds him, towels him dry, and worries when he disappears.

Tom functions as a living interruption to her controlled life: caring for an animal means accepting unpredictability, noise, and need. This theme shows that connection does not arrive through speeches or grand gestures; it arrives through small acts—coffee waiting at a café, a shared curry lunch, a cat rubbing against her ankles in the dark.

These moments matter because they teach Margaret that independence does not have to mean emotional starvation. The theme also suggests that “family” can be built through mutual trust rather than social roles.

Calvin, initially a jittery colleague, becomes someone she protects and later shares a meal with. Joe becomes someone who believes her when others refuse.

Even the garden dinner at the end signals a shift: she is no longer eating alone in her cottage, using work as a substitute for companionship. Care becomes a form of resilience, not sentimentality.

The story’s emotional resolution rests on this theme: truth is important, but so is the discovery that Margaret does not have to carry danger and grief by herself.

Identity, Reinvention, and the Cost of Speaking Up

Margaret’s sense of self is shaped by a past professional exile that still controls how she expects the world to treat her. Being punished for reporting falsified research results taught her that truth-telling has consequences, and that institutions can rewrite a person’s identity with rumors and paperwork.

This history explains why she is both rigid and courageous: rigid because she clings to procedures as protection, courageous because she has already survived being cast out once. The Botanist’s Assistant portrays reinvention as something that happens in fragments rather than a clean transformation.

Margaret finds work at a garden center, then Deaver recognizes her intelligence and offers a second chance, but the fear of losing that chance never fully leaves. That fear is why Blackstone’s threats land so powerfully; he is not only threatening her job, he is threatening her restored identity as someone who belongs in science.

Her investigation is therefore personal: if she fails, she risks becoming the “difficult woman” again, the scapegoat, the employee the institution can discard. The theme also explores how documentation becomes a tool for identity preservation.

Her notebooks are not just records; they are proof that she sees clearly, that her mind is reliable even when others try to dismiss her. When she is ordered to hand over data and stop speaking, it echoes her earlier silencing, forcing her to decide whether she will protect herself by complying or protect truth by resisting.

The story shows that reinvention requires allies: Deaver gave her the first opening, but Joe’s support and the eventual exposure make it possible for her to keep standing. Identity in this book is not about self-esteem slogans; it is about whether a person’s integrity can survive pressure from systems that benefit when people stay quiet.

Margaret’s final position—still in science, still precise, but less alone—suggests that speaking up does not stop being risky, but it can become survivable when truth is paired with community and evidence.