The Briar Club Summary, Characters and Themes

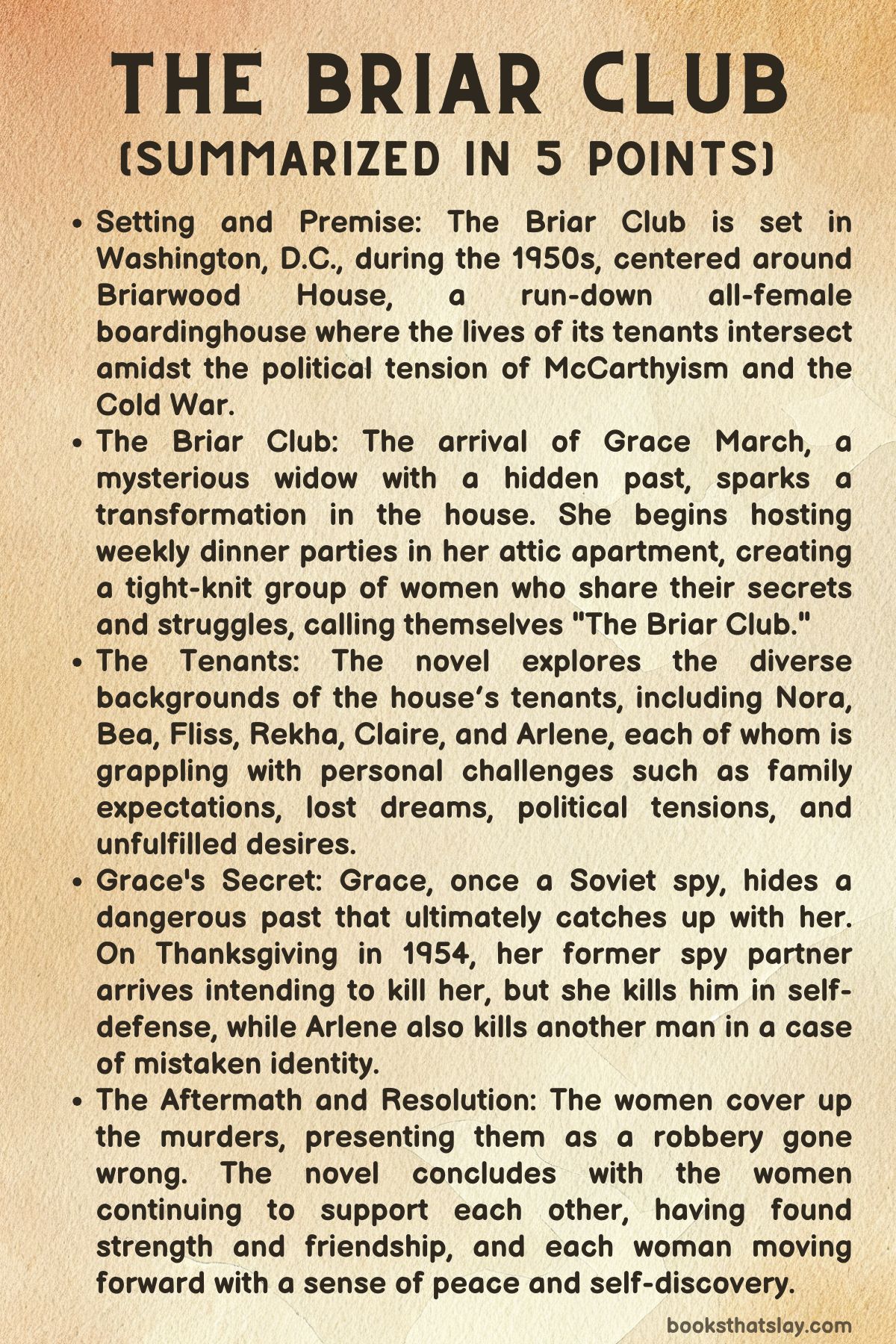

The Briar Club by Kate Quinn is a layered historical novel set in postwar Washington, D.C., focusing on the residents of Briarwood House, a crumbling boarding house where secrets simmer behind thin walls.

The novel blends humor, heartbreak, and moments of suspense as it explores the lives of women and men trying to carve out dignity, freedom, and identity in a world brimming with McCarthyism, domestic constraints, racial prejudice, and the aftermath of war. Through Thursday night suppers, a murder investigation, and personal awakenings, the tenants find unlikely kinship while wrestling with who they are, who they love, and what they are willing to risk for freedom and belonging.

Summary

The novel opens on Thanksgiving 1954, with detectives investigating a murder in Briarwood House, an old Washington, D.C. boarding house that has witnessed the struggles and small joys of its diverse residents.

The house itself offers a perspective on the scene, amused at human frailties and violence sparked by family tensions and buried resentments.

The story then rewinds to June 1950, introducing Pete, a 12-year-old boy who lives with his strict mother, Mrs. Nilsson, and his sister Lina, who dreams of baking despite her mother’s coldness.

The arrival of Grace March, a lively woman with a knack for ignoring house rules, changes the air in Briarwood. Grace starts hosting Thursday night suppers, drawing in the other tenants and forming what Pete comes to call the Briar Club.

Among them are Fliss, a young British mother, Nora, who seeks independence from her chaotic family, Bea, a former women’s baseball player sidelined by injury, Reka, a bitter Hungarian refugee hiding her artistic past, and Claire, a determined secretary with dreams of owning a home.

Nora, working in the National Archives and waitressing on weekends, meets Xavier Byrne, who operates a poker game and is tied to the Warring crime family.

Drawn to him yet wary, she begins a relationship, learning to claim her independence even as she grapples with Xavier’s violence and the risks of his lifestyle.

Their connection ends after Xavier is arrested, and Nora chooses her autonomy over love, despite their deep bond.

Reka, who once smuggled Klimt sketches out of Germany, is fired after Arlene, a fervent HUAC supporter, reports her as a communist sympathizer.

Desperate and angry, Reka confronts the Sutherland family, whose patriarch stole her sketches years before, and finds an unlikely ally in Sydney Sutherland, who quietly helps her reclaim the art.

This act reignites Reka’s artistic spirit, and she returns to painting, determined to reclaim her dignity and purpose.

Fliss, overwhelmed by single motherhood while her husband serves in Korea, battles exhaustion and guilt.

She befriends Sydney, who is trapped in an abusive marriage, and helps her access experimental birth control. Fliss, bolstered by the support of the Briar Club, plans to resume her nursing career, finding a renewed sense of agency in shaping her future while supporting other women.

Bea, once a star in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, mourns the loss of her career but finds solace in working as a gym teacher.

She starts a relationship with Harland, an FBI agent disillusioned with McCarthy-era paranoia, while rediscovering her love for baseball during community games.

With Grace’s encouragement, Bea secures a role as a scout for the Senators, reclaiming her connection to the sport she loves.

Claire, working at the Senate and taking side jobs, hoards her savings in hopes of buying a home.

Her tough exterior shields a history of poverty and survival after losing her parents during the Depression. She falls in love with Sydney Sutherland, longing to rescue her and her son from Barrett’s violence.

Claire’s plans to help Sydney escape are crushed when Sydney is unable to flee, leaving Claire heartbroken but determined.

Meanwhile, Grace’s true identity is revealed. She was once Galina Stepanova, a Soviet spy sent to America but disillusioned by her mission and the lies she was taught.

She defected, taking documents meant for the Soviet Union, and rebuilt her life at Briarwood, finding purpose in nurturing others.

She helps Lina compete in a baking contest in New York and fosters hope in the children, even reuniting them with their estranged father.

The Thanksgiving feast in 1954 becomes a turning point. Kirill, Grace’s former handler, arrives to kill her, injuring Fliss before Grace and Bea manage to stop him, leading to his death.

As the tenants debate Grace’s fate, Arlene secretly calls the police, but before they arrive, Barrett Sutherland storms in, seeking Sydney, and in the chaos, Arlene kills him with Bea’s baseball bat.

The residents fabricate a story to protect themselves, presenting the events as a robbery gone wrong, with Harland using his FBI credibility to support the account.

Grace’s files are destroyed, protecting her and the others while dismantling evidence that could fuel further McCarthy-era witch hunts.

Grace decides to leave Briarwood for the safety of the tenants but takes Arlene with her, sensing that she, too, needs saving.

The epilogue, narrated by Pete in 1956, shows the residents moving forward. Pete and Lina’s father returns, preventing the house’s sale.

Nora reconciles with Xavier. Fliss moves to Massachusetts to work as a nurse. Bea and Harland continue their relationship.

Reka passes away after resuming her art, and Sydney and Claire move to Bermuda for a fresh start.

Grace writes from New York, preparing for Arlene’s wedding, noting that despite everything, the Briar Club’s spirit endures, with each member carving out a future shaped by the community they built together at Briarwood.

Characters

Pete Nilsson

Pete, at twelve years old when the story begins, serves as a window into Briarwood House’s dynamics with his protective love for his sister Lina and his complicated relationship with his demanding, cold mother, Mrs. Nilsson. His longing for his absent father, to whom he writes unanswered letters, reflects his deep desire for stability and affection in a household that offers neither warmth nor encouragement.

Despite his mother’s rigid rules, Pete shows quiet resilience, finding moments of small rebellions guided by Grace’s advice to learn to get around rules rather than be crushed by them. As he grows, Pete emerges as the moral compass of the Briar Club, becoming its “man of the house” by the end.

When he makes the decisive call to protect Grace and the tenants, it showcases the evolution of a child forced to mature too quickly into a young man shaped by the house’s tangled found-family dynamics.

Lina Nilsson

Lina’s character is built on both vulnerability and hope. Her “lazy eye” and her clumsy baking initially mark her as an object of ridicule, and her mother’s stinginess prevents her from receiving medical care or emotional support.

However, her passion for baking, encouraged by Pete and nurtured by Grace, becomes a symbol of defiance and growth. Lina transforms from a timid girl mocked for her failures to a confident young baker, willing to enter competitions and capable of winning prizes.

Her progression is a quiet but profound assertion of self-worth in a world that constantly underestimates her. She embodies how small victories can bring light to constrained lives.

Grace March

Grace is the heart of The Briar Club, a woman of layered secrets and unwavering presence. Arriving at Briarwood House as a mysterious, charismatic tenant, she quickly becomes the center of its unofficial family with her Thursday suppers, nurturing presence, and sharp advice.

Grace’s identity as a former Soviet spy who has rejected her homeland’s ideology adds complexity to her role. It frames her as a woman who has chosen to adopt a new nation despite its flaws, seeking redemption and a place of belonging.

Her nurturing is practical and bracing rather than sentimental, urging characters like Pete, Lina, and even Arlene toward growth and survival. Grace’s final confrontation with Kirill and her choice to protect her chosen family over her past allegiance underscore her transformation into a fierce guardian.

She becomes someone who saves others while carrying the heavy price of her own past.

Nora Walsh

Nora embodies the struggle for autonomy in a society designed to limit women’s choices, balancing her desire for love with the need to protect herself from exploitation and control. Her romance with Xavier Byrne, a man connected to crime yet capable of tenderness, highlights her internal conflict between safety and passion.

She grapples with her fear of male violence rooted in her past abusive relationship and her family’s manipulative demands. Nora’s resolve to maintain her independence, even when her heart is torn by love, positions her as a resilient figure who claims her right to her own life.

She fights to maintain her autonomy despite societal expectations that push her toward dependency.

Reka Mueller

Reka’s character is that of an embittered survivor, carrying the weight of displacement, loss, and the erosion of her identity as an artist. Once a vibrant figure in the Berlin art world, Reka is reduced to shelving books in a library, her talents unnoticed in her adopted country.

Her scathing cynicism and sharp tongue mask her pain, yet her passion for art and her integrity emerge when she reclaims the stolen Klimt sketches, asserting her right to her past and future. Her gradual decision to begin painting again represents a flicker of hope.

It shows that even those who have endured profound losses can reclaim fragments of joy and purpose.

Fliss Orton

Fliss’s story is a raw, honest portrayal of post-partum depression, exhaustion, and fear of motherhood in a world fraught with political tension and personal uncertainty. Alone with her infant daughter while her husband is stationed in Korea, Fliss struggles with feelings of inadequacy and terror over the future.

She illustrates the crushing expectations placed upon women to find fulfillment in motherhood regardless of their circumstances. Her eventual courage to help Sydney seek birth control, her rekindling of purpose through her nursing skills, and her connection to the Briar Club’s support network allow Fliss to transform her fear into action.

She reclaims her agency over her body and future.

Bea Verretti

Bea’s character is defined by her fierce independence and the grief of losing her baseball career, which was her deepest passion and identity. Her transition from a professional athlete to a teacher who is asked to teach home economics is a cruel irony that she meets with humor and determination.

Bea’s refusal to conform to traditional expectations of marriage, even when pursued by Harland, and her decision to pursue a new career as a talent scout show her refusal to be contained by societal norms. She embodies the spirit of a woman who values her freedom and purpose above all else.

Claire Hallett

Claire is a pragmatic survivor, hardened by poverty, parental loss, and societal prejudice. Her ambition to buy her own home is born from the insecurity of a childhood marked by instability and discrimination, driving her to engage in morally ambiguous acts, including theft and sex work, to secure her future.

Her relationship with Sydney is one of quiet, desperate love, highlighting Claire’s longing for intimacy and partnership. She wrestles with her past and her survival instincts while attempting to secure a stable future.

Her heartbreak when Sydney fails to flee with her reveals the vulnerability beneath her brash exterior. It underscores the complex interplay between her need for love and her drive for security.

Arlene Hupp

Arlene represents blind allegiance to authority and societal prejudice, aligning herself with McCarthy’s witch hunts in a desperate attempt to gain status and security. Her self-righteousness and lack of self-awareness make her an outsider within the Briar Club.

Her character’s transformation during the crisis—when she kills Barrett in self-defense and submits to Grace’s guidance—reveals a potential for growth beneath her rigid exterior. Arlene’s final trajectory, where she moves toward marriage with a compliant partner under Grace’s guidance, suggests that even the most hardened characters can find a new path when guided by the right influences.

The limits of her transformation, however, remain open to interpretation.

Sydney Sutherland

Sydney is a tragic figure trapped in an abusive marriage, her life dictated by her controlling husband, Barrett, and her social position. Her initial connection with Fliss over shared English accents and her desperate attempts to control her reproductive choices highlight the quiet battles many women face behind closed doors.

Sydney’s eventual role in helping Reka reclaim her stolen past and her attempt to escape with Claire demonstrate her courage. Her failure to leave her husband in time underscores the tragic realities many women face when trying to break free from abusive systems.

Xavier Byrne

Xavier is a complex figure straddling the line between lawlessness and a personal code of honor. His attraction to Nora and his desire for a legitimate life contrast sharply with his readiness to resort to violence to protect his interests, including the murder of George Harding.

His willingness to give Nora space, even while loving her, shows his respect for her autonomy. Xavier’s narrative serves to challenge easy moral binaries.

It shows that goodness can sometimes wear rough edges in a world that demands survival above all.

Themes

Found Family and Communal Bonds

In The Briar Club, the presence of found family is quietly but firmly rooted in every corridor of Briarwood House. The residents, despite differences in class, origin, and ideology, begin to form a chosen family that both shields and heals them.

Grace’s Thursday suppers are more than communal meals; they become a quiet rebellion against loneliness and societal atomization in post-war Washington. They turn strangers into allies and, in many cases, lifelines for survival.

Grace’s mentorship of Pete and Lina as she coaxes Lina’s hidden baking talent, Bea’s baseball games providing Pete with moments of childhood otherwise denied to him, and the way Nora finds the strength to face her abusive family by being around Xavier and the Briar Club all reflect how these informal bonds transform individual resilience into collective fortitude. The house itself, personified as a narrator, stands as a vessel for this chosen kinship, its old walls embracing secrets and providing shelter from the storms of poverty, trauma, and social exclusion.

This theme also manifests in moments of shared vulnerability. Fliss’s postpartum depression softened by Grace’s humor and honesty, and the eventual unified decision to cover up the murders to protect one of their own, become pivotal moments.

Each resident’s growth is intimately tied to the small but significant support they receive from the others. It underscores that survival and flourishing in a harsh, suspicious world often demand a family you build, not one you are born into.

Gender, Power, and Bodily Autonomy

Through characters like Fliss, Sydney, and Nora, The Briar Club critiques the limits placed upon women’s bodies and choices in 1950s America while illuminating their quiet yet profound acts of defiance. Fliss’s fear of further pregnancies despite societal and marital expectations of motherhood, Sydney’s entrapment in an abusive marriage compounded by the denial of reproductive autonomy, and Nora’s refusal to let her family or Xavier’s underworld ties dictate her path illustrate the constant negotiations women undertake to reclaim power in environments determined to strip it away.

The tension between prescribed domesticity and personal ambition becomes a relentless undercurrent, with Bea’s struggle to remain connected to baseball and Grace’s transformation from a Soviet spy to an American protector of her boarding house illustrating the refusal to conform to narrow definitions of womanhood. The text also shows how female solidarity, as seen in Fliss aiding Sydney to access birth control trials or Grace protecting Claire from the consequences of betrayal, is an essential, often underrecognized form of resistance.

Women in The Briar Club do not merely survive patriarchal constraints; they find slivers of freedom through collective courage, personal boundaries, and the gradual redefinition of their worth beyond the domestic sphere. Each act of reclaiming autonomy, however small, becomes a victory in a world that denies women power over their own bodies.

Political Paranoia and Moral Complexity

Against the backdrop of McCarthyism and Cold War hysteria, The Briar Club explores the corrosive effect of political paranoia on individuals and communities while emphasizing the moral ambiguity inherent in survival. The constant surveillance, loyalty tests, and fear of communist infiltration shape many characters’ lives.

Arlene’s blind devotion to HUAC’s cause, Harland’s growing disillusionment with the FBI, and Grace’s hidden identity as a defector from the USSR all reveal the damage wrought by a climate of suspicion. Yet, the novel refuses to paint ideology in simple binaries.

Grace, once a Soviet spy, becomes a nurturing figure who resists authoritarianism more authentically than many Americans chasing communists in their midst. The characters are repeatedly confronted with difficult moral choices.

Nora must decide whether love is worth complicity, Harland wrestles with the ethics of destroying Grace’s file, and the entire Briar Club collaborates to protect one of their own despite the risk of being seen as traitors themselves. The narrative suggests that in a world obsessed with ideological purity, true patriotism and humanity often lie in protecting the vulnerable, even if it requires moral compromise.

The Red Scare becomes not only a historical backdrop but a mirror reflecting how fear can distort justice, turning neighbors into informants while inadvertently creating bonds of radical empathy among those targeted.

Identity, Reinvention, and Belonging

The Briar Club is filled with characters seeking to reinvent themselves, driven by a deep yearning for belonging in a society that would otherwise reject them. Grace reinvents herself from a loyal Soviet operative into a nurturing protector, severing ties with her past to embrace the imperfect freedoms of America.

Bea, forced to leave her baseball career due to injury, reimagines her life by becoming a talent scout, maintaining her connection to the sport she loves. Claire, shaped by the trauma of poverty and her parents’ deaths, reinvents herself from a girl who would steal to survive into a woman capable of planning a rescue for the woman she loves, even if her methods remain morally questionable.

Nora’s journey from an obedient daughter in an Irish family to an independent woman who can say no to familial and societal pressures is another testament to reinvention. The boarding house itself becomes a haven for these reinventions, providing a space where identities can be negotiated and redefined away from the gaze of a judgmental society.

The residents of Briarwood learn that true belonging often requires the courage to reshape one’s identity, discarding the parts dictated by others and embracing those formed through struggle, self-awareness, and the gentle acceptance of those who have chosen to love and support them.

Violence, Trauma, and Healing

Violence and its aftermath are omnipresent in The Briar Club, whether it is the physical brutality of domestic abuse, the psychological scars left by war and displacement, or the violence inherent in a society fueled by paranoia and bigotry. Fliss’s postpartum depression, Sydney’s bruises inflicted by her husband, Reka’s trauma from fleeing Nazi Germany, and Grace’s memories of Leningrad’s starvation and loss are quietly layered into the narrative.

They illustrate how trauma can shape, break, and also build resilience within individuals. The novel does not shy away from showing how violence begets further violence, as seen in Xavier’s underworld justice, Grace’s final confrontation with Kirill, and Arlene’s killing of Barrett.

Yet, healing is depicted not as a return to normal but as the creation of new paths forward, often facilitated by the Briar Club’s communal warmth, humor, and practical support. The Thursday suppers, the laughter shared over Arlene’s absurd salad, and the collective action to protect each other after the murders become moments of healing.

These moments allow characters to reclaim small joys and moments of connection despite the violence surrounding them. The Briar Club suggests that while trauma cannot be erased, it can be soothed by community, love, and the daily acts of care that transform survival into living.