The Busy Body Summary, Characters and Themes

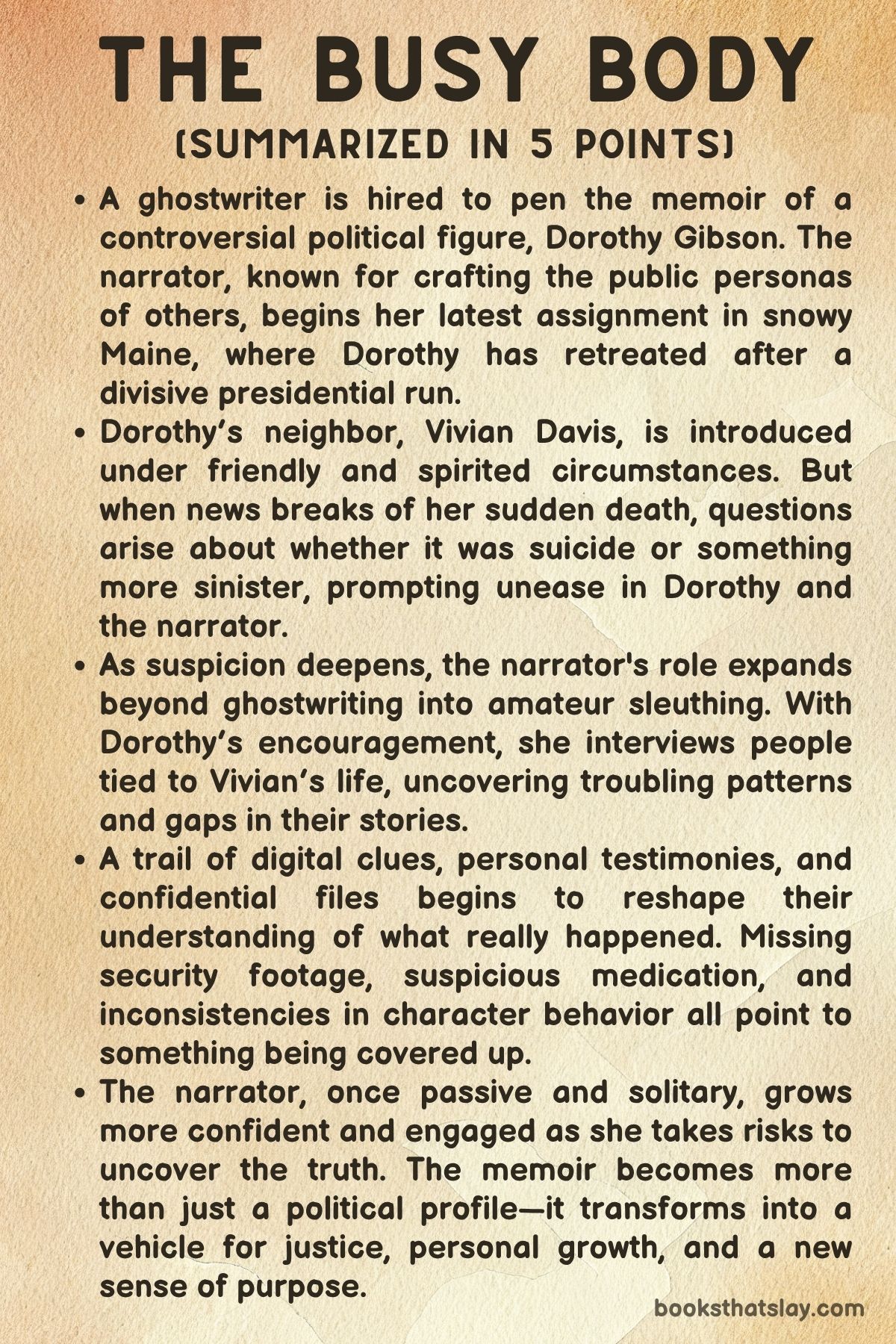

The Busy Body by Kemper Donovan is an inventive and sharply observant blend of political intrigue, personal memoir, and murder mystery, all told through the unique lens of a ghostwriter. The story follows a cynical and reclusive writer who is hired to help former presidential candidate Dorothy Gibson pen her memoir.

What begins as a straightforward job soon entangles her in a labyrinth of secrets, lies, and an unexpected death. With an undercurrent of feminist wit and commentary on fame, power, and privacy, the novel subverts the conventions of both detective fiction and political drama, creating a layered and genre-blending narrative about truth, identity, and reinvention.

Summary

A seasoned ghostwriter, known for her detachment and skill at crafting others’ stories, receives an urgent call from her agent Rhonda. She learns that Dorothy Gibson, a controversial former Independent presidential candidate, wants her to ghostwrite a memoir.

For the narrator, this represents a major opportunity—Dorothy’s public and political life is rich with scandal, reinvention, and potential for a sensational book. Despite misgivings, especially about flying to a remote estate in Maine, the narrator agrees.

Upon arrival, she’s met by Leila Mansour, Dorothy’s policy advisor. Leila informs her this will be a highly personal memoir and that she’ll need to live on-site.

The ghostwriter, though hesitant, agrees. At Dorothy’s heavily guarded estate, she meets Denny, the unexpectedly relaxed young bodyguard, and Dorothy herself—much smaller and warmer than expected.

During their initial dinner, the ghostwriter signs a non-disclosure agreement, officially beginning the project. She senses the seriousness and intimacy of the role, a far cry from her previous gigs.

Soon after, she meets Dorothy’s son, Peter, a cheeky and possibly ambitious figure. He shares odd local news items, including a homeless man’s death and a missing swim instructor named Paula Fitzgerald—details that seem minor at first but plant early seeds of mystery.

Dorothy remains emotionally guarded, but over time, she and the ghostwriter develop a working rapport. When Peter returns to New York, the estate becomes quieter, allowing for deeper interviews and moments of emotional honesty, especially around Dorothy’s late mother.

A trip to a local liquor store introduces Vivian Davis, an eccentric and wealthy neighbor who lavishes praise on Dorothy. Shortly after this encounter, news breaks that Vivian has died by suicide.

Dorothy and the ghostwriter attend the memorial at Vivian’s extravagant home, the Crystal Palace, where the narrator meets Vivian’s husband Walter Vogel, his assistant Eve Turner, and Vivian’s sister Laura. Eve, distressed and suspicious, confides that she found the suicide unlikely and is frustrated with delays in toxicology reports.

Laura, meanwhile, seems unstable and inconsistent, casting doubt on the official narrative.

The narrator’s suspicions grow after overhearing Eve argue with the medical examiner and talking with Laura, who suggests an altercation involving a man named Paul—a staffer with unclear duties—on the night of Vivian’s death. Laura is later caught trying on Vivian’s jewelry, which makes her seem manipulative.

Walter’s controlling behavior, especially toward Laura, adds to the web of suspicion. Further cracks appear when a teenager named Alex Shah accuses Vivian of inappropriate behavior.

His parents, Anne and Samir Shah, corroborate his claim but admit they hesitated to report it. Anne remembers hearing strange noises from Vivian’s room after the supposed time of death.

The investigation leads to Walter’s ex-wife Minna and their son Bobby Hawley, who both express bitterness and appear emotionally disturbed. They claim to have been watching Dateline during the murder, a timeline Dorothy finds suspect.

Their hatred of Walter raises the possibility of a calculated frame-up. Dorothy resolves to check surveillance footage for clues about who truly had access to the estate.

The tension escalates when Dorothy is questioned by police and media attention explodes. Despite warnings, she and the narrator press on.

After a fraught dinner, the narrator finds herself emotionally and physically drawn to Denny, leading to a night of intimacy. The encounter reveals her complicated relationship with vulnerability and control.

Meanwhile, Leila is furious with Dorothy for continuing the investigation, worried about political fallout. But Dorothy is undeterred.

Accompanied by Officer Choi, Dorothy and the narrator visit the morgue, where they meet a young, energetic medical examiner named Sheila Hasan. What they discover there shocks the narrator: the body under the sheet isn’t Vivian’s, despite official identification.

Dorothy remains eerily calm, suggesting a deeper plan in play. She drops cryptic clues—references to water damage, surveillance footage, and Anne Shah—but leaves the narrator in suspense.

The climax unfolds at the Crystal Palace. Dorothy gathers all parties for a dramatic revelation.

She explains that the body in Vivian’s room belonged to Paula Fitzgerald, the missing swim instructor. Vivian and Walter had discovered Paula’s body in a stream and staged a fake suicide.

With Vivian’s phone and the conveniently broken security camera, they created the illusion that Vivian had died. Vivian then attended her own memorial disguised as her sister Laura, complete with prosthetics and padded clothing, to watch the fallout and manipulate public sentiment.

The motive: to boost a fraudulent Kickstarter campaign for a political satire project.

However, the scheme unraveled when Walter decided to leave Vivian for Eve. Enraged, Vivian killed Walter, marking the point where her plot turned from fraud to murder.

Her confession, delivered with dramatic flair, exposes a tangle of grief, rage, and betrayal. She had been consumed by the very illusions she tried to construct, unable to bear the lies of others even as she spun her own.

In the aftermath, Dorothy confronts her son Peter, discovering he betrayed her by revealing her location to Walter and Vivian. This shatters the last remnants of her trust in him.

The narrator, meanwhile, reflects on her choices. Though drawn to Denny and emotionally affected by recent events, she chooses solitude and writing over connection.

Standing alone in the Crystal Palace, she considers the cost of emotional self-protection and the enduring need for creative purpose.

The Busy Body ends as it began—with the ghostwriter alone, quietly chronicling the lives of others while guarding her own. But now, her understanding of identity, truth, and storytelling is forever altered by the secrets she uncovered and the people she dared to see more clearly.

Characters

The Ghostwriter (Narrator)

The unnamed ghostwriter at the heart of The Busy Body is a figure shaped by solitude, cynicism, and professional dexterity. She operates from the shadows of other people’s narratives, orchestrating stories with precision while keeping herself emotionally distanced.

Her self-declared aversion to private jets and her discomfort with personal vulnerability speak volumes about her cautious, tightly guarded personality. Yet, as she becomes immersed in Dorothy Gibson’s world, her boundaries start to erode.

Living under the same roof as Dorothy, encountering unsettling mysteries, and finding herself emotionally—and later physically—entangled with the bodyguard, she experiences a slow unraveling of her isolation. Her obsessive relationship with true crime fuels her investigative instincts, which in turn draw her deeper into the mystery of Vivian Davis’s death.

The ghostwriter is complex: intellectually curious, emotionally self-sabotaging, and profoundly driven by the pursuit of meaning through storytelling. Her decision in the end to choose solitude and authorship over companionship underscores a defining trait—her persistent belief that creativity, however lonely, is her ultimate truth.

Dorothy Gibson

Dorothy Gibson, once a towering figure in the political world, is depicted with layered contradictions that make her a mesmerizing presence. Publicly formidable and privately composed, Dorothy transcends the archetype of a fallen political titan.

Her disciplined work ethic, commanding intellect, and unyielding composure under pressure suggest a woman forged in the crucible of power. However, her domestic side—relaxed, literate, and emotionally self-contained—adds unexpected depth.

She is not given to outbursts or sentimentality, but instead reveals vulnerability in carefully rationed moments, especially when recalling her mother or handling betrayal. Dorothy’s leadership instincts persist even in retirement, as she orchestrates investigations, commands attention, and ultimately delivers the narrative’s emotional and intellectual climax.

Her ability to navigate political scandal, family betrayal, and murder with equal poise is not just a testament to her resilience but also to her constant reinvention. By the novel’s end, Dorothy emerges as both myth and woman—guarded but transparent, disillusioned but fiercely alive.

Leila Mansour

Leila Mansour serves as Dorothy’s policy aide and emotional ballast, moving between political savvy and personal loyalty with remarkable ease. Initially presented as charming and intelligent, she reveals herself to be a deeply pragmatic figure, concerned not only with Dorothy’s safety and reputation but also with the operational chaos surrounding them.

Leila’s warmth is genuine, but it never dulls her edge—she is protective, strategic, and often the voice of reason when emotions run high. Her tension with Dorothy over the murder investigation points to deeper anxieties about the limits of loyalty and the cost of public perception.

Yet even amid clashes, Leila never abandons Dorothy, suggesting a bond that transcends professional obligations. She is, in many ways, the narrative’s conscience—a reminder of the real-world implications of decisions made in pursuit of truth or justice.

Denny (The Bodyguard)

Denny, the deceptively casual bodyguard, at first presents himself as a friendly, almost flirtatious distraction. His laid-back demeanor masks a reflective nature, and his philosophical banter with the ghostwriter reveals a mind that contemplates duality and human complexity.

He becomes a mirror for the narrator’s own internal contradictions—attracted to danger but wary of attachment, seeking connection but fearing its cost. Their sexual encounter, charged with emotional intensity, is less about romance and more about vulnerability colliding with desire.

Denny’s presence underscores the narrator’s struggle with intimacy: he offers the possibility of companionship, yet she ultimately chooses the path of isolation. While he remains somewhat elusive, Denny’s function in the narrative is critical—he disrupts the narrator’s control, challenges her comfort, and amplifies her loneliness by representing the road not taken.

Peter Gibson

Peter, Dorothy’s son, is a figure wrapped in charisma and ambiguity. His breezy charm and irreverent wit hint at someone who has lived in the shadows of greater power, yet is savvy enough to carve out his own path.

There is a performative edge to Peter, an ability to manipulate mood and attention, which makes him at once endearing and suspect. His potential political ambitions mirror his mother’s past, but his decisions—particularly selling Dorothy’s location to Vivian and Walter—reveal a self-serving core that ultimately fractures his relationship with her.

Peter is not simply a disappointment; he is a cautionary tale of legacy gone astray, a reminder that proximity to greatness doesn’t ensure moral fortitude. His arc ends with estrangement, revealing the chasm between public charm and private betrayal.

Vivian Davis

Vivian Davis is a magnetic and enigmatic presence whose posthumous resurrection propels the novel’s central mystery. At first a seemingly manic but benign neighbor, her shocking suicide and subsequent unraveling as a criminal mastermind reshape the story’s tone entirely.

Vivian faked her own death, assumed the identity of her sister “Laura,” and orchestrated an elaborate scheme of financial and emotional manipulation. Her motivations are complex: a mix of grief, betrayal, a hunger for attention, and rage over Walter’s betrayal.

Vivian is a performance artist in the cruelest sense—living and dying through masks and illusions. Her presence looms over every character, shaping their reactions, confessions, and suspicions.

She is the novel’s chaotic force, capable of both tragic vulnerability and monstrous control.

Walter Vogel

Walter Vogel, Vivian’s husband and a skin regeneration entrepreneur, is defined by control and detachment. He is the kind of man who projects power quietly—more interested in managing outcomes than in forming genuine connections.

His treatment of Laura, his ambiguous relationship with Eve, and his willingness to use Vivian’s death for personal gain all paint a picture of a manipulator who believes he can outwit the world. Walter’s actions are not as flamboyant as Vivian’s, but they are equally insidious.

His death at Vivian’s hands is not just a narrative twist—it is poetic justice, a reckoning for a man who underestimated the emotional fury of the woman he tried to discard.

Eve Turner

Eve Turner begins as a peripheral figure—Walter’s assistant, overwhelmed and observant—but evolves into a subtle disruptor. Her suspicions about Vivian’s death, her conflict with Laura, and her strained role in the Vogel household make her a quiet vessel of tension.

She operates on the edge of scandal and loyalty, simultaneously victim and enabler. Eve’s emotional fatigue and moral uncertainty highlight the toxicity of the environment she navigates, and her eventual revelations push the investigation forward.

Though not central to the action, Eve’s perspective deepens the novel’s themes of complicity, manipulation, and the invisible toll of proximity to power.

Laura Duval (Vivian’s Alter Ego)

Laura Duval is a fictional identity adopted by Vivian Davis as part of her faked death narrative, but the character of “Laura” grows into a gothic echo of Southern melodrama and familial dysfunction. The portrayal is exaggerated—drunken, theatrical, flirtatious—but it serves a purpose: to sow confusion, elicit pity, and obscure truth.

When the real Vivian is revealed beneath this identity, the grotesque performance of “Laura” becomes a chilling metaphor for how women are taught to perform vulnerability and madness for survival or spectacle. “Laura” is the ultimate mask—a protective fiction that allows Vivian to monitor the aftermath of her own disappearance and execute her final act of vengeance.

Anne, Samir, and Alex Shah

The Shah family introduces a deeply unsettling subplot that touches on power, belief, and trauma. Alex’s accusation that Vivian assaulted him, and his parents’ subsequent handling of the situation, reveal a web of moral grayness.

Anne and Samir’s decision not to report the incident immediately—out of fear, shame, or disbelief—exposes the failings of parental judgment and the complexities of adolescent vulnerability. Alex’s outburst during the memorial is a pivotal moment, forcing a crack in the carefully curated social veneer.

The Shahs, while not directly responsible for Vivian’s fate, embody the ripple effects of silence, guilt, and the moral failures that make such crimes possible.

Minna and Bobby Hawley

Minna and Bobby Hawley represent grotesque familial decay—Walter’s ex-wife and estranged son, both driven by resentment and consumed by bitterness. Minna is obsessive, venomous, and performative in her hatred for Walter, while Bobby is a stunted figure, trapped in emotional infantilism.

Their shared dysfunction is both comedic and tragic, exaggerating the theme of fractured family legacies. Their lies and theatricality make them suspicious in the murder investigation, but their true role is thematic—they are a distorted mirror of the damage left in Walter’s wake.

Through them, the novel examines how some people inherit pain and pass it on without ever breaking the cycle.

Themes

The Construction and Manipulation of Identity

In The Busy Body, the notion of identity is not a fixed truth but a narrative construct, constantly being shaped by how others perceive it and how individuals choose to represent themselves. At the heart of the novel lies the ghostwriter’s task—crafting a memoir for Dorothy Gibson—which becomes more than simply recounting a life; it turns into an exercise in curating a legacy.

Dorothy’s insistence on a deeply personal memoir, contrasted with her instinct to remain emotionally guarded, underscores the tension between authenticity and control. She wants to reveal herself but only on her own terms, shaping her story to reclaim power over the narrative that has been imposed on her by the public and media.

This theme is taken to an extreme in the case of Vivian Davis, who fakes her own death and then reinvents herself as “Laura Duval,” using elaborate costuming and theatricality to live as both victim and observer. Vivian’s manipulation of her own death as a spectacle not only mirrors Dorothy’s attempt to reframe her life through a memoir but critiques the performative nature of public identity itself—how easily facts can be rearranged and consumed as truth.

The ghostwriter, whose own failed novel haunts her, is also negotiating her sense of self, wavering between anonymity and the desire to leave a creative legacy. Her role is to efface her voice in favor of others, yet she becomes an accidental detective and emotional participant, shifting from observer to actor in the drama.

Through characters who rewrite their lives for different audiences—political, familial, romantic—The Busy Body suggests that identity is a collaborative fiction, one shaped by need, pain, and the fantasy of reinvention. In a world where truth is not always fixed, the boundary between personhood and performance blurs.

Power, Corruption, and Gender

Power in The Busy Body is often portrayed as a currency negotiated through gendered spaces and unequal dynamics. Dorothy Gibson’s status as a former presidential candidate and political figure foregrounds the difficulty of attaining and maintaining authority as a woman in public life.

Despite her formidable intelligence and resolve, she exists within a society quick to discredit female ambition or reduce complex women to symbols. The memoir becomes a mechanism not only to control her public story but to resist the historical diminishment of women who wield power.

Yet her battle is not only against external systems—it’s also internal, fighting disillusionment and betrayal from within her closest circles.

This theme expands through the stories of other women—Eve Turner, the underestimated assistant; Anne Shah, who navigates her son’s trauma and social expectations; and most potently, Vivian Davis, whose theatricality masks a profound rage at the erosion of her agency. Vivian’s fake death and eventual murder of Walter are acts of desperation and vengeance.

Her transformation into “Laura Duval” and her manipulation of public mourning are radical assertions of power through deception. While morally compromised, her actions expose how traditional power structures—especially those linked to wealth, marriage, and public image—can push women to extreme acts to reclaim control.

Men in the novel, from the oily Walter to the manipulative Peter, often occupy positions of unearned authority or opportunism. Peter’s betrayal of his mother is especially significant, undermining familial loyalty in pursuit of self-interest and illustrating how even personal relationships are contaminated by power plays.

The theme interrogates the intersection of gender and power not just in overt institutions like politics but also in intimate relationships, exposing how control is exerted subtly through secrecy, manipulation, and narrative dominance.

Truth, Storytelling, and the Ethics of Narrative

As a ghostwriter, the narrator functions as the novel’s moral compass and narrative lens, drawing attention to the ethical dilemmas embedded in storytelling. She is tasked with excavating Dorothy Gibson’s truth for a memoir, but quickly finds herself caught in a web of lies surrounding Vivian Davis’s supposed death.

This shift from memoir to mystery highlights the central tension: how can truth be determined in a world saturated with performance and competing versions of reality? The narrator’s own professional identity—built on shaping others’ stories—becomes unstable as she grapples with the responsibility of revealing facts versus respecting privacy.

Her instincts as a writer often conflict with her growing emotional entanglements, particularly as she unearths secrets that many would prefer remain buried.

Throughout the novel, storytelling is shown not only as a tool for personal catharsis or political control but as a weapon. Vivian’s use of a false narrative to manipulate grief and extract money from the public through a Kickstarter campaign is a grotesque parody of truth-telling.

Her eventual confession is stylized like a final act in a drama, suggesting that even genuine remorse is filtered through theatrical convention. Dorothy, too, must decide what parts of her life to expose and what to withhold, balancing transparency with self-preservation.

The ghostwriter is left to navigate these grey areas, questioning whether her role is to document, judge, or protect.

In exposing multiple layers of deception and intention, The Busy Body reveals storytelling as an act fraught with ethical compromise. The line between journalist and voyeur, artist and opportunist, victim and manipulator, becomes dangerously thin.

The book suggests that truth is not a fixed destination but a negotiation, and those who tell stories—whether for money, legacy, or justice—must reckon with the consequences of shaping reality.

Solitude, Connection, and the Cost of Vulnerability

Loneliness permeates The Busy Body, touching nearly every character in subtle and overt ways. The narrator’s professional detachment has calcified into emotional distance; she defines herself by invisibility, by being the vessel for other people’s voices.

Her single novel—her only attempt at creative self-expression—was a commercial and emotional failure, making her retreat even further into ghostwriting. This chronic solitude becomes her armor, protecting her from rejection but also isolating her from meaningful intimacy.

Her tentative relationship with Denny, the Bodyguard, is marked by moments of warmth and mutual curiosity, yet she ultimately chooses solitude over connection, unable or unwilling to let someone fully into her life.

Dorothy, too, is surrounded by people but emotionally compartmentalized. Her authority and fame create barriers rather than bridges, and her trust is eroded by betrayal—most painfully by her own son.

Despite her public life, she has no true confidants, which perhaps explains her rare openness with the ghostwriter. The connection between the two women—intense, fraught, but mutually respectful—emerges as one of the novel’s most poignant dynamics.

It reveals how intellectual intimacy can offer a temporary balm to emotional isolation, yet it is also fleeting and contingent on circumstance.

The tragedy of Vivian Davis adds another layer. Her performative existence, the need to fake her death to feel seen, and the extreme loneliness that led her to kill, all speak to the terrifying emptiness that can exist beneath a polished surface.

Even her transformation into “Laura Duval” suggests a yearning to be part of something—grief, community, control—rather than remain erased by others’ decisions. In portraying these varied forms of loneliness and emotional hunger, the novel suggests that connection is not only a human need but also a dangerous vulnerability.

To be seen is to risk betrayal, and for many, it’s safer to remain hidden. The final image of the narrator choosing solitude in the Great Hall crystallizes this theme: the refusal of comfort, the rejection of intimacy, and the complicated relief of standing alone.

Feminist Resistance and Moral Ambiguity

The women in The Busy Body are not sainted figures or passive recipients of injustice—they are active agents navigating systems stacked against them. Whether it’s Dorothy running for president as an Independent, Eve Turner trying to be more than a background assistant, or Vivian staging her own death as a political and financial maneuver, each woman resists the roles society expects her to play.

Their methods are not always morally clean. Vivian commits murder.

Dorothy manipulates media narratives. The ghostwriter withholds evidence to protect Dorothy’s reputation.

But the novel does not condemn them outright. Instead, it presents their choices as responses to a world where traditional ethics often protect abusers and penalize survivors.

Vivian’s act of faking her death is not only revenge against Walter but a radical attempt to control her own story and legacy. Her confession, while theatrical, is also a reclamation—a refusal to be remembered as merely a tragic victim.

Dorothy, for all her restraint, is willing to bend rules, twist arms, and strong-arm the police to achieve justice. The ghostwriter, usually silent and complicit, begins to assert herself by choosing what to write and what to leave out.

In showing women exercising agency in morally grey terrain, the novel suggests that resistance often comes at the cost of purity. Feminism here is not about moral high ground but about survival and strategic navigation of power.

This moral ambiguity—whether protecting a client, supporting a friend, or avenging a betrayal—becomes a form of rebellion. It resists the expectation that women must be likable, ethical, or emotionally accessible in order to be heard.

By foregrounding this complexity, The Busy Body argues for a feminism that acknowledges contradiction, celebrates resilience, and embraces the messy, often uncomfortable choices women make to retain power in an unequal world.