The Conjurer’s Wife Summary, Characters and Themes

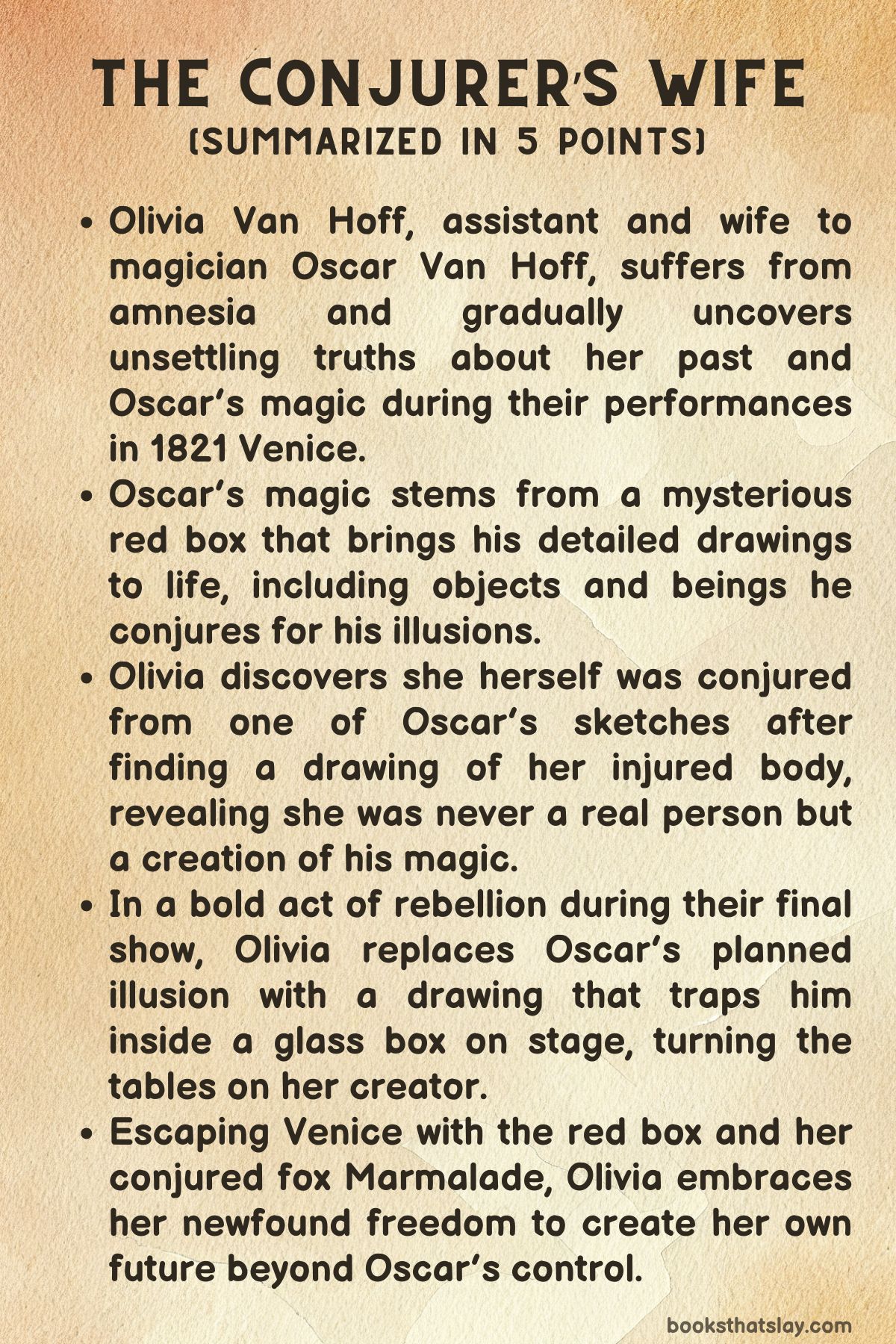

The Conjurer’s Wife by Sarah Penner is a richly imagined historical fantasy set against the atmospheric backdrop of 1821 Venice. It tells the story of Olivia Van Hoff, a magician’s assistant who begins to question the truth of her existence, her past, and her marriage.

As whispers of sea witches and mysterious shipwrecks begin to surface, Olivia is drawn into a journey of self-discovery that transforms her from a beautiful illusion onstage into a woman who takes control of her own magic. Blending themes of power, memory, and identity, the novel explores the boundaries between illusion and reality through a magical and emotionally charged lens.

Summary

In December 1821, inside the opulent Teatro La Fenice in Venice, Olivia Van Hoff stands before a sold-out crowd in a performance filled with spectacle. Dressed in a glittering amethyst gown with bells in her hair, she appears every inch the confident magician’s assistant.

The audience is enthralled, waiting for the star magician—her husband, Oscar Van Hoff—to begin the night’s illusions. But even as Olivia plays her part, a quiet defiance simmers within her.

She stands slightly off-mark on stage, a small but intentional rebellion against Oscar’s tightly controlled script.

Olivia’s role in Oscar’s show is more than just decorative. She is beloved by audiences for her poise and elegance, and yet beneath the surface, her life is haunted by an unsettling void.

Ever since her wedding night, she has suffered from amnesia caused by a mysterious fall. That same night marked the beginning of Oscar’s rise to fame.

Olivia has since lived in a state of dependence on her husband, plagued by fragmented memories and a sense that something crucial has been taken from her.

During the evening’s performance, Oscar conjures a baby fox in a spectacular moment meant to awe the crowd. But it’s Olivia’s gentle interaction with the creature, whom she names Marmalade, that endears her to the audience.

Behind the curtain, Oscar chastises her for deviating from the performance, while the theater’s proprietor praises her charisma and presence.

As preparations begin for Oscar’s grandest illusion yet—The Fatalist’s Fête, in which he plans to conjure a white stallion inside a glass box—tensions rise. Olivia senses something unsettling behind Oscar’s increasingly powerful conjurations.

At an elegant after-party that evening, she overhears whispered rumors about shipwrecks near Positano. Locals blame sea witches for the tragedies, but the story seems oddly familiar to Olivia.

In a secluded gallery, she finds a watercolor of three red-haired women labeled as “The witches of Positano. ” The image hits her with an inexplicable wave of recognition and longing.

For the first time, she begins to believe her past may not be what she has been told.

Back at their home, Olivia investigates Oscar’s hidden storage cupboard. There she finds a red box containing pastel sketches of the objects Oscar conjured during the night’s show—evidence that his magic originates from these illustrations.

Alongside these are crumpled drawings of failed experiments, including one of a redheaded woman annotated with obsessive questions about her powers and wealth. But the most jarring discovery is a rendering of Olivia herself—bloodied and broken, exactly as she imagines she looked after the fall that caused her memory loss.

This image confirms her worst fears: she was not injured that night—she was created.

The implications are staggering. Olivia realizes that Oscar conjured her, not just illusions or animals.

She is not a wife who lost her memories. She is a woman conjured from a sketch, constructed to play the perfect assistant and partner in his show.

Everything she thought she knew about her identity is a fabrication born of Oscar’s ambition.

The night of The Fatalist’s Fête arrives, and Olivia sees her chance to reclaim her agency. Feigning illness, she sneaks away backstage and replaces Oscar’s carefully prepared drawing of the stallion with one of her own making.

When Oscar performs the illusion, he ends up conjuring himself into a glass box—trapped by the very magic he once used to dominate others. The crowd roars with applause, believing it to be part of the performance.

With Oscar contained, Olivia takes the red box, the baby fox Marmalade, and her newfound sense of control. She flees the theater and rides away in a carriage, drawing raspberries into existence from her sketchbook and feeding them to Marmalade.

No longer bound by the past or by Oscar’s version of reality, she begins a new chapter of self-authorship.

Her destination is the south—toward the witches of Positano, toward the fragments of memory that feel like truth, and toward a future she will create herself. Armed with the knowledge that she is not merely a conjurer’s wife but a conjurer in her own right, Olivia sets out to build a life where she is the artist, the magician, and the woman behind her own story.

Characters

Olivia Van Hoff

Olivia Van Hoff is the emotional and narrative center of The Conjurer’s Wife, a woman who initially appears as the graceful and controlled magician’s assistant but soon reveals herself to be much more than a supporting act. Her public persona is one of calm elegance and subdued devotion to her husband Oscar, but beneath this façade lies a woman brimming with quiet resistance and growing suspicion.

Suffering from amnesia caused by a mysterious fall on her wedding night, Olivia begins the story as someone shaped by uncertainty, reliant on the carefully constructed world around her. Yet even in this dependent state, there are cracks in the illusion—her subtle deviation from the stage mark and her small acts of rebellion signal an inner strength and a desire for autonomy.

As she starts to unravel the truth about her origins, Olivia undergoes a radical transformation. Her discovery of Oscar’s conjuring drawings—including one of herself bloodied and broken—forces a reckoning with her identity.

The realization that she was not only injured but conjured into existence propels Olivia into a state of self-liberation. Her final act of swapping Oscar’s drawing during the grand finale demonstrates her reclaiming agency, not just over her body or career but over her very being.

Olivia’s journey from passive illusion to powerful creator encapsulates the book’s themes of autonomy, artifice, and liberation. By the end, she is no longer defined by the roles imposed on her—wife, assistant, muse—but has become a conjurer of her own reality, journeying toward selfhood with the fox Marmalade and a sketchbook full of possibility.

Oscar Van Hoff

Oscar Van Hoff is the celebrated magician whose charisma and spectacle mask a deeply manipulative and morally corrupt core. To the public, he is a genius performer and loving husband, but behind the curtain, Oscar is controlling, exploitative, and dangerously ambitious.

His initial portrayal as a demanding partner who chastises Olivia for minor missteps soon gives way to something more sinister as his secrets unfold. Oscar’s power lies not merely in his sleight of hand or showmanship, but in his dark mastery of conjuration—he brings to life objects and beings from sketches, a skill he uses to shape his world with an almost godlike arrogance.

His marriage to Olivia is revealed to be an illusion of the highest order, with Olivia herself being one of his conjured creations. This revelation repositions him as a kind of mad artist or mythic figure who would create life only to control it, to mold it to his will.

The red box of sketches Olivia discovers paints Oscar as both desperate and cruel, particularly in his repeated failures to conjure money or harness the powers of the witches of Positano. Ultimately, his fate—trapped within the glass box by his own conjuring—serves as a poetic punishment.

His magic turns on him, exposing the hollow core of his illusion. Oscar becomes a cautionary figure, a man who sought omnipotence through art and manipulation but was undone by the very subject he thought he owned.

Marmalade

Though small in stature, Marmalade, the baby fox conjured during Oscar’s stage performance, holds a unique symbolic weight in The Conjurer’s Wife. Marmalade represents Olivia’s first true connection, an act of spontaneous affection that stirs both the audience’s love and Olivia’s sense of self.

More than just a cute animal, Marmalade embodies the untamed and instinctive parts of Olivia that were previously suppressed. By naming and caring for the fox, Olivia begins to trust her impulses and emotions—an essential step in her awakening.

Marmalade becomes a silent companion in her journey toward autonomy, a reminder that even within artifice, something real and loyal can emerge. The fox’s presence at Olivia’s final escape scene emphasizes the theme of rebirth; as Olivia conjures raspberries for Marmalade from her own pastel sketches, she moves into a phase of creation that is driven by joy and freedom, rather than control or spectacle.

The Witches of Positano

The witches of Positano occupy a liminal space in the narrative—half myth, half memory—but their role in shaping Olivia’s sense of self and history is vital. First introduced through whispered gossip and a watercolor painting, these red-haired women evoke a powerful sense of familiarity and belonging in Olivia.

They are initially framed as villains responsible for shipwrecks, but Olivia’s emotional response to the image suggests otherwise. Rather than evil, the witches represent a matriarchal legacy of power, perhaps even the original source of the conjuring magic that Oscar sought to appropriate.

Olivia’s recognition of them marks a turning point in her internal transformation—a sign that her fragmented memory is reconnecting to a deeper truth. The witches are thus symbolic ancestors or spiritual guides, whose memory fuels Olivia’s break from Oscar’s narrative and her own awakening as a conjurer in her own right.

Themes

Power, Autonomy, and Control

The dynamic between Olivia and Oscar Van Hoff in The Conjurer’s Wife illustrates how power can be concealed behind charisma and spectacle. Oscar, a successful and celebrated magician, exercises near-total control over Olivia—onstage and off.

His dominion is not overtly violent but is deeply psychological and rooted in manipulation. Olivia, once thought to be merely his assistant, is revealed to be a literal product of his magic, conjured into existence and molded to fit his narrative.

This revelation reframes their entire relationship as one of creator and creation rather than equal partners, casting Oscar’s control in a deeply sinister light. His control extends to the choreography of their stage performances, the regulation of her memory through carefully curated omissions, and even the crafting of her very body and personality.

Olivia’s growing resistance—symbolized early on by the slight repositioning of her mark on stage—signals a burgeoning autonomy. These small acts culminate in her final, bold move: replacing Oscar’s conjuring sketch during the finale and thereby reversing the power imbalance.

The act is not just about sabotage but reclamation. It marks her refusal to be manipulated any further and affirms her capacity to shape her own destiny.

Power in the novel is therefore not just a matter of dominance, but also of creation—those who can imagine, draw, and conjure wield it. Olivia’s final grasp of that power, along with her escape, transforms her from a passive assistant into an autonomous agent of her own future, underlining how control can be resisted and eventually overthrown when self-awareness and courage align.

Identity and Memory

Memory in The Conjurer’s Wife functions as a site of both loss and discovery, shaping Olivia’s understanding of who she is and who she was meant to be. When the novel opens, Olivia is suffering from amnesia supposedly caused by a fall on her wedding night.

This conveniently timed incident not only robs her of her history but ensures Oscar’s dominance over her perception of reality. The absence of memory leaves her in a liminal space where she must rely on others—especially her husband—for cues about her past, making her malleable and easier to control.

She is praised and admired for her poise and performance, but inwardly she questions her origins, particularly as subtle hints begin to stir old emotions and challenge the official story.

Her gradual recovery of memory is catalyzed by visual stimuli—art, newspaper clippings, sketches—each one drawing her closer to an emotional truth that cannot be articulated by logic alone. The image of the red-haired women, labeled witches, triggers not fear but warmth and longing, suggesting an intuitive recognition of belonging.

These moments of clarity suggest that identity is not merely rooted in facts or chronology but in emotional and spiritual resonance. When Olivia discovers the sketch of herself, broken and bloodied, the final piece falls into place: she wasn’t merely injured, she was created.

That realization is traumatic, but it also offers liberation. She understands now that memory can be stolen, manipulated, even rewritten—but it can also be reclaimed.

The regaining of memory allows her to claim a new identity not as Oscar’s wife or assistant, but as a conjurer in her own right, capable of creating herself anew.

Illusion Versus Reality

The entire framework of The Conjurer’s Wife rests on the tension between illusion and reality, not just in the context of stage magic but in every corner of Olivia’s life. Her marriage, her identity, her memories, even her body, all turn out to be crafted illusions, designed by Oscar to entertain, to control, and to maintain his public image.

The audience at Teatro La Fenice, like Olivia herself, is enraptured by spectacle without questioning what lies beneath. The theme critiques society’s complicity in embracing illusions when they are beautiful, pleasurable, or comforting.

For the audience, Olivia is a glamorous assistant; for Oscar, she is a carefully designed object. That duality illustrates how easily reality can be overwritten by performance.

As Olivia becomes more conscious of the layers of deception around her, she begins to see how reality has always been within her grasp—it was simply hidden beneath layers of spectacle and lies. The conjured objects—each drawn in pastels and animated through magic—become metaphors for how reality is manipulated.

They are beautiful, fleeting, and fragile, much like the story Oscar has constructed around their lives. The real act of magic, however, comes when Olivia takes control of that illusion-making power.

By creating raspberries for Marmalade or orchestrating Oscar’s downfall during his own finale, she exposes illusion for what it is: a tool, not a truth. This inversion—the performer becoming the orchestrator—demonstrates that the line between what is real and what is fabricated is not fixed, but subject to who holds the means of creation.

Feminine Reclamation and Witchcraft

Though witches are initially introduced through hearsay and superstition, their presence in The Conjurer’s Wife becomes a symbol of powerful, intuitive femininity. The red-haired women of Positano, labeled “sea witches” by fearful villagers, represent a maternal, protective, and creative force that is deeply misunderstood and maligned by patriarchal structures.

The depiction of these women challenges traditional ideas of witchcraft as malevolent or chaotic. Instead, they come to symbolize what Olivia has lost—a lineage of women who possess not only power but moral clarity and emotional depth.

The watercolor triggers a sense of longing and instinctive recognition, suggesting that Olivia may share a bond with them that predates even her conjured existence.

Oscar’s fascination with the witches, as revealed in his annotated sketches, is not reverent but extractive. He seeks to harness their power and wealth, to use their essence as fuel for his own conjuring.

This exploitative gaze mirrors historical dynamics where women’s spiritual and emotional labor was taken without acknowledgment or respect. Olivia’s alignment with the witches reclaims that narrative.

She begins as a tool of male magic but ends as an inheritor of a female tradition of creation. Her final acts are not just of escape but of spiritual reconnection—with the fox as a familiar, with the conjured fruit as a symbol of abundance, and with the road ahead leading to Positano.

This movement from object to subject, from conjured to conjurer, signifies a powerful act of feminine reclamation. Witchcraft in the novel is not about spells or hexes—it is about knowing, creating, remembering, and restoring.

Olivia does not become a witch in the traditional sense; rather, she embraces a lineage of empowered womanhood that allows her to redefine magic on her own terms.