The Dark Hours Summary, Characters and Themes

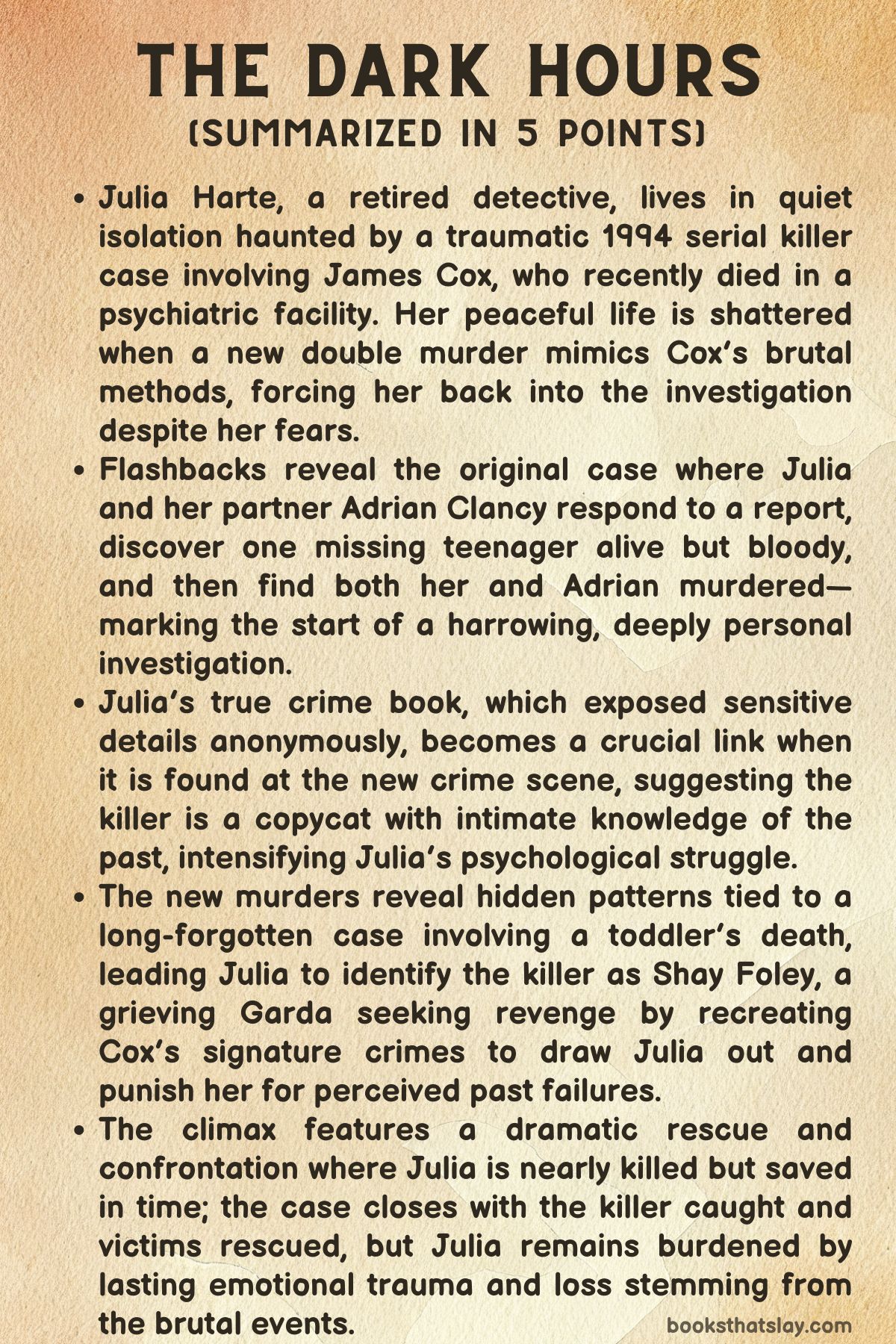

The Dark Hours by Amy Jordan is a psychological crime thriller that traces the life of former detective Julia Harte as she is pulled back into a decades-old nightmare. After years of retreating into anonymity in a remote Irish village, Julia’s quiet life is disrupted when a series of brutal murders mimic those committed by a long-dead serial killer she once helped apprehend.

What begins as a reluctant return to her past transforms into a harrowing journey of personal reckoning, trauma recovery, and justice. This intricately layered narrative unfolds across dual timelines—1994 and 2024—exploring how memory, grief, and buried secrets continue to shape the present.

Summary

Julia Harte lives in reclusion in Cuan Beag, a coastal village in Ireland, having left her life as a detective behind. Her quiet existence revolves around routine, her dog Mutt, and managing chronic anxiety linked to a traumatic case from her early years in the Garda.

Three decades ago, she was instrumental in apprehending James Cox, a serial killer whose crimes haunted her ever since. When news breaks that Cox has died in a psychiatric hospital, Julia is unsettled—not relieved.

His death doesn’t close the door on the past but threatens to reopen wounds that never fully healed.

The story returns to 1994 when Julia was a junior Garda working with her partner, Adrian Clancy. During a late-night call, they encounter a bloodied teenage girl, Louise Hynes, whose friend Jeanette Coyle is still missing.

Julia acts on instinct and enters a suspicious house nearby, only to discover a disturbing soundscape of recorded cries and strange silence. It’s a setup.

Power is cut and Julia narrowly escapes the trap, only to find Adrian and Louise murdered in their squad car. The trauma from that night forever shifts her career and psyche, anchoring the pain that will follow her into the future.

In 2024, Cox’s death ignites a new series of murders that replicate his former patterns. Julia’s attempt at living under the radar falters when her presence is outed at a local gathering, raising questions about her past.

A call from Des Riordan, her former boss, confirms her fears: two new victims have been found—college students killed in the same manner as Cox’s original targets. Julia’s own criminal procedure textbook is discovered at the scene, tying her uncomfortably close to the crimes.

Riordan suspects a copycat and asks her to return to Cork to consult. Reluctantly, she agrees, knowing she can no longer ignore the signs.

The book alternates timelines between Julia’s early career and the current investigation. In the present, Julia researches social media and finds posts showing Elena and Hannah, the recent victims, had injuries that mirror Cox’s signature method.

A night club video captures the moment Hannah was attacked, though the footage lacks clarity. The investigation uncovers a lead—a backpack left in a cloakroom with a logo tied to a defunct graphic design company.

Ian Daunt, a former employee of that company and editor at Julia’s old publishing house, becomes a person of interest. He admits to requesting old coroner’s files for a book on Cox, but his alibi is flimsy, and his connections to the crimes grow increasingly suspicious.

The narrative also reexamines Julia’s strained personal life in 1994. After Adrian’s murder, Julia confronts a dismissive police hierarchy, battles grief, and sees her marriage to Philip begin to unravel.

Philip wants safety and a family, while Julia remains committed to justice and her profession. Their emotional disconnection deepens after Adrian’s funeral, where Philip’s discomfort with her professional drive becomes evident.

Julia’s dogged determination to stay in the investigation causes further alienation.

As more clues surface, the team realizes the killer might be drawing Julia into a twisted game by recreating elements from her past. A young woman, Grace York, is the next victim to go missing.

Her apartment is found to resemble a crime scene from 1994, even down to details like scattered pebbles and a power outage. Julia and Riordan navigate professional tensions—particularly with the skeptical DS Armstrong—but persist in following these disturbing leads.

Julia’s past and present continue to collide when she visits her ex-husband Philip in the hospital after he’s brutally attacked in a similar style to the other victims. Though he survives, he ends their marriage for good.

Julia is devastated but finds purpose in her work again. She pushes deeper into the case and eventually uncovers a vital clue: traces of antifouling paint under a victim’s fingernails.

This points to a boatyard near Knockchapel, the town she once lived in.

She and Armstrong discover Grace York on a boat named The Léa-Camille—a chilling tribute to Cox’s deceased partner and child. Grace is alive but soon disappears from the hospital.

The investigation reaches a shocking climax when Grace returns, revealing herself as the killer. Years earlier, Julia had rescued her from a pedophile’s basement.

Now, emotionally shattered and feeling abandoned, Grace seeks revenge. She blames Julia for saving her but not protecting her afterward.

Ian Daunt, her accomplice, helped her plan the murders as a way to rewrite a narrative they felt left them behind.

Grace attacks Julia at her temporary residence and holds Riordan’s granddaughter hostage. Julia, though wounded, manages to incapacitate Grace with pepper spray.

Authorities arrive in time to take both Grace and Daunt into custody. The confrontation leaves Julia physically and emotionally scarred, and her belief in the systems she once upheld is further tested.

Riordan dies shortly after, another casualty of a life tethered to violence and justice.

In the aftermath, Julia reflects on the cumulative weight of her career, her broken relationships, and the people she couldn’t save. At Riordan’s funeral, she finds a glimmer of connection when she sees Philip again—older, slower, but still present.

Their moment of recognition signals that while the past cannot be undone, some fragments of love and memory remain intact.

The Dark Hours ends not with resolution but with acknowledgement: of what was lost, what was survived, and what must still be carried. Through Julia Harte, the novel portrays the relentless imprint of violence on a life, and how the pursuit of truth can offer both purpose and pain.

Characters

Julia Harte

Julia Harte, the emotional and psychological anchor of The Dark Hours, is a deeply complex character whose life is marked by trauma, moral integrity, and professional obsession. A retired detective inspector, Julia has retreated to the quiet village of Cuan Beag in hopes of escaping the ghosts of her past—specifically, the horrific case of serial killer James Cox, which nearly destroyed her.

Her life in exile is controlled, filled with ritual and isolation, accompanied only by her elderly dog, Mutt. Yet, even in this supposed safety, Julia remains a prisoner of fear, grief, and unresolved guilt.

The announcement of Cox’s death does not bring closure, but rather reopens psychological wounds that never healed. Her character oscillates between strength and vulnerability: she is tenacious and fiercely intelligent, yet consumed by self-doubt and remorse.

In her younger years as a junior Garda in 1994, Julia exhibits a boldness that both endangers and defines her. Her decision to enter a crime scene alone is emblematic of her instinct-driven nature, but it also sets the stage for a lifetime of consequences when her partner Adrian Clancy is murdered.

This moment, pivotal in her emotional development, creates a fracture that reverberates through her marriage, her career, and her sense of self. In 2024, despite her reluctance, she answers the call to rejoin an investigation eerily reminiscent of the Cox murders, showcasing a moral compass that outweighs her fear.

Her evolution from idealistic officer to wounded yet unwavering investigator illustrates her resilience and commitment to justice, even as she grapples with the haunting question of whether her pursuit of justice has ever been enough.

Des Riordan

Des Riordan serves as Julia’s long-time mentor and former superior, a steady presence throughout her tumultuous career. In both 1994 and 2024, Des represents institutional authority tempered by personal loyalty.

Unlike many of their male colleagues who dismissed Julia’s insights early in her career, Des eventually recognizes her potential and advocates for her inclusion, especially when the stakes rise. His trust in Julia becomes most evident when he calls her back into the fold in 2024, urging her to lend her expertise to the emerging copycat murders.

His willingness to see beyond hierarchy and protocol and focus on competence and justice make him one of the few stable figures in Julia’s life.

Des is not immune to the consequences of the past. His involvement in the Cox case and the new spate of murders leave him emotionally and physically vulnerable.

When he is attacked in a manner echoing Cox’s old methods, it cements the idea that the past still lives in the present, and that even the steadiest hands can falter under its weight. His death near the end of the novel brings not only sorrow but serves as a symbolic close to an era of Julia’s life—one filled with guidance, paternal concern, and painful truths.

Des’s legacy is embedded in Julia’s sense of duty and in her final decisions, making him a moral touchstone who, even in death, continues to influence the story’s arc.

Philip Harte

Philip Harte, Julia’s husband, is a tragic figure whose trajectory mirrors the emotional fallout of a marriage strained by trauma, ambition, and divergent life goals. In 1994, Philip is introduced as a man deeply in love but increasingly overwhelmed by his wife’s dangerous career and her relentless pursuit of justice.

He represents domestic stability and the desire for a traditional life—children, security, emotional availability. Yet his needs come into sharp conflict with Julia’s trauma and professional dedication, particularly after the murder of her partner and the ensuing investigation that consumes her.

Over time, their relationship becomes more strained, their connection reduced to routines filled with unspoken tensions and diverging values.

The emotional crescendo of Philip’s arc comes with his stabbing and subsequent hospitalization. Though he physically survives, the incident creates an irreparable fracture in their relationship.

His decision to separate from Julia, despite her constant bedside presence, is laden with a mixture of pain, betrayal, and emotional resignation. Philip does not simply represent a failed marriage; he symbolizes the cost of Julia’s life choices and the impossibility of balancing love with a profession steeped in darkness.

Their final encounter at Des Riordan’s funeral, where he appears older, smiling, and leaning on a cane, serves as a bittersweet coda—offering a glimpse of unresolved tenderness and the enduring, if distant, nature of love once shared.

Ian Daunt

Ian Daunt is a fascinating study in ambiguity and obsession. Initially introduced as a peripheral character—an employee at Julia’s former publishing house with a curiosity about old coroner’s reports—he gradually emerges as a deeply entangled figure in the unfolding mystery.

His professional veneer, tied to writing and graphic design, masks a more sinister obsession with James Cox and the history of violence connected to Julia. His knowledge of the past murders is too intimate, and his interview with police—casual at first, but increasingly defensive—raises alarm bells.

Ian’s calm exterior hides layers of fascination and possible emulation, which come to light when the logo of his defunct company is linked to a backpack left at a crime scene.

His partnership with Grace York is the final unraveling of his character. Whether motivated by loyalty, manipulation, or shared psychosis, Ian’s complicity in the murders is undeniable.

Yet, he is also a tragic figure in his own way—perhaps a man who lost himself in the romanticized darkness of crime lore, craving recognition and purpose through horrifying means. He becomes a conduit for resurrecting Cox’s legacy, and his fall into criminality serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of fetishizing violence and losing oneself in the mythos of evil.

Grace York

Grace York is the most tragic and terrifying character in The Dark Hours, embodying the lingering psychological damage of childhood trauma and the dark complexity of survival. Introduced initially as a potential victim, Grace’s arc transforms into one of the novel’s most shocking revelations.

Once a child rescued by Julia from a pedophile’s basement, Grace grows up in the shadow of violence, abandonment, and identity erasure. Her pain is not just physical or emotional—it is existential.

Having never received the ongoing care or recognition she needed, she constructs a new identity rooted in revenge, seeking to make herself unforgettable by mimicking the horrors that once consumed her life.

Her motives are deeply personal and terrifyingly logical within the twisted framework of her trauma. Feeling erased from Julia’s legacy, forgotten and unacknowledged, Grace engineers a chilling reenactment of Cox’s crimes to force a reckoning.

She is intelligent, manipulative, and heartbreakingly aware of the impact of trauma. Her orchestration of the murders, her symbolic gestures, and her final confrontation with Julia—where she holds Rosie, Des’s granddaughter, at knifepoint—are acts of desperation, vengeance, and a cry for recognition.

Grace is not just a villain; she is a reflection of systemic failure, untreated trauma, and the fragile line between victim and perpetrator.

Adrian Clancy

Adrian Clancy’s presence haunts the novel like a ghost—his death in 1994 not only alters the trajectory of Julia’s life but becomes the emotional fulcrum for much of her internal conflict. As Julia’s partner, Adrian is portrayed as steady, compassionate, and perhaps the only person who truly understands her drive.

Their bond is deep, grounded in shared purpose and mutual respect. His murder—shocking and senseless—is one of the defining moments of the story, and its psychological aftermath reverberates through Julia’s every decision in the decades that follow.

Adrian’s death marks the beginning of Julia’s guilt, her insomnia, and her fixation with justice. Her repeated visits to his widow, her memories of their time together, and the knowledge that she left him alone in the squad car that fateful night, become emotional burdens she cannot put down.

In many ways, Adrian represents the life Julia might have had—one where trust and partnership could flourish—but his absence leaves a void filled only by self-recrimination and determination. Though he appears only briefly in the flashbacks, Adrian’s spirit looms large, a reminder of both what was lost and what drives Julia to continue seeking justice, no matter the cost.

Themes

Trauma and Psychological Residue

The core of The Dark Hours is animated by the persistent aftermath of psychological trauma and its long-term effects on memory, identity, and functioning. Julia Harte, the protagonist, is not just haunted by what happened in 1994—she is entirely reconstructed by it.

Her retreat into a solitary life in Cuan Beag, adherence to rigid safety rituals, and avoidance of public interaction all reveal a mind battling with unprocessed shock and guilt. The murder of her partner Adrian Clancy becomes a psychic wound that never closes, its presence echoed in her insomnia, anxiety, and extreme vigilance.

Even decades later, the announcement of James Cox’s death acts as a psychological trigger, collapsing the barrier she built between her past and present. The story does not suggest that trauma can be overcome by sheer willpower or rationality; instead, it portrays it as a corrosive, lingering presence that shapes choices, relationships, and even professional ambition.

The revelation that Grace York, the killer in the present day, was also a childhood survivor of trauma, complicates this further. Her psychosis emerges not from pure malice but from abandonment and untreated emotional wounds, implying that trauma, left unacknowledged, can metastasize into unpredictable violence.

Julia’s eventual confrontation with Grace does not symbolize closure so much as it reasserts the impossibility of full psychological resolution. The past remains a live wire, with every step forward shadowed by the unresolved weight of memory and pain.

The novel presents trauma as not only a personal burden but also a public hazard—when survivors are unsupported, the consequences ripple outwards, sometimes lethally.

Female Professionalism and Gendered Power Structures

Throughout The Dark Hours, Julia’s professional identity is repeatedly contested by patriarchal structures that seek to confine, dismiss, or undermine her competence. In the 1994 timeline, her intuition and experience during the investigation into James Cox are consistently brushed aside by male superiors who view her as a subordinate rather than a peer.

Her exclusion from key briefings and strategic decisions, even after the murder of her partner, highlights the deep-rooted institutional sexism within law enforcement. Julia’s persistent efforts to reinsert herself into the investigation are not framed as overreach but as necessary resistance to a system that diminishes female expertise.

Her promotion in the years that follow is not portrayed as triumph, but as a delayed recognition of what should have been evident earlier. Even in the present, Julia’s role is questioned when she re-enters the investigation.

DS Armstrong’s initial dismissiveness signals that despite her track record and experience, her authority is still subject to scrutiny in ways her male counterparts are not. This thematic thread is compounded by her personal life, especially her deteriorating marriage with Philip, who ultimately resents her professional priorities.

The story illustrates how women in high-stakes professions often have to choose between personal fulfillment and professional dedication, a false dichotomy that exacts a painful toll. Julia’s resilience is notable not because she overcomes these challenges easily, but because she persists despite them—carving out a space for herself in a field that was never designed with her in mind.

Obsession with Legacy and Identity

In The Dark Hours, the desire to shape or reclaim one’s legacy is a powerful motivating force that blurs the boundaries between heroism, hubris, and destruction. Julia’s writing of a criminal procedure book initially appears as an effort to educate, perhaps to offer clarity after years of painful ambiguity.

But its unexpected popularity, and the way it is sensationalized and misinterpreted, shifts its meaning from educational tool to a public artifact—one that draws unwanted attention and, eventually, implicates her in a series of violent crimes. Her involvement in the present-day investigation is driven not only by professional obligation but by a deeper, almost existential need to ensure her story—her legacy—is not defined solely by failure and loss.

This desire to reclaim agency is mirrored, in a darker way, by Grace York. Grace, who as a child was rescued by Julia and subsequently forgotten by the system and by Julia herself, feels erased from the narrative of survival.

Her transformation into a killer is not just about vengeance; it is an attempt to reassert her place in a history that neglected her, to force the world to remember her suffering. Ian Daunt’s obsession with Cox’s legacy through his book project serves as a third perspective on the same theme—fascination with the past as a means to shape the present.

The novel suggests that stories, especially those involving violence and survival, are never just private; they become public property, fought over by those who lived them and those who seek to exploit them.

Moral Responsibility and the Cost of Inaction

Julia’s struggle with her past is not confined to survivor’s guilt—it also involves deep moral reckoning over choices made and opportunities missed. In 1994, her decision to enter the house alone during the first discovery of Cox’s crimes reflects her determination, but also initiates a chain of consequences that lead to Adrian’s death.

The sense that she could have done more, or done differently, gnaws at her even thirty years later. Her initial refusal to join the new investigation in 2024—her retreat to Cuan Beag and her desire for anonymity—are portrayed not as cowardice but as fatigue and fear, yet they are equally framed as forms of moral avoidance.

Des Riordan’s insistence that she return is not a request for expertise but a call to moral duty, challenging her to stop hiding behind past wounds. Similarly, the deaths of Elena, Hannah, and the targeting of Grace York point to systemic failures—by police, by institutions, and by individuals—to protect those in danger.

The novel does not excuse Grace’s actions but highlights that her path to violence was paved by inaction and abandonment. Julia’s eventual confrontation with Grace, and her refusal to kill her despite being provoked, becomes a complicated moment of ethical clarity.

She reclaims her moral authority not by exacting revenge or delivering final justice, but by choosing compassion over destruction, even when it nearly costs her life. The novel insists that justice is not simply about punishment—it is about bearing responsibility, even when doing so requires great personal cost.

Isolation and the Search for Connection

Loneliness and isolation dominate Julia’s life in both the past and present, but the novel consistently portrays this solitude as a condition imposed rather than chosen. After Adrian’s death and the subsequent unraveling of her marriage, Julia becomes increasingly cut off—from colleagues, from community, and from her own emotional world.

Her routines in Cuan Beag are not mere quirks; they are protective mechanisms designed to prevent vulnerability. The companionship of her dog Mutt is telling—he is the only being she trusts completely, a symbol of the simple, non-verbal bond she can still tolerate.

In Cork, her relationship with Des Riordan becomes a lifeline, albeit one complicated by duty and trauma. Their connection is grounded in mutual understanding and shared grief, providing moments of authentic emotional exchange in a story otherwise dominated by suspicion and violence.

When Des is murdered, the loss is not just tactical but emotional, threatening to collapse the last meaningful bond Julia possesses. The temporary unity with Armstrong and others during the investigation is significant not because it resolves her isolation, but because it momentarily alleviates it—proving that connection, however fragile, is possible even in the midst of horror.

The final encounter with Philip at Des’s funeral serves as a quiet, poignant reminder that not all connections are obliterated by trauma. Though they no longer share a life, they share a history.

Julia’s journey, then, is not one of romantic or social reintegration, but of emotional awakening—she may remain alone, but she is no longer entirely disconnected.