The Dead of Winter Summary, Characters and Themes | Sarah Clegg

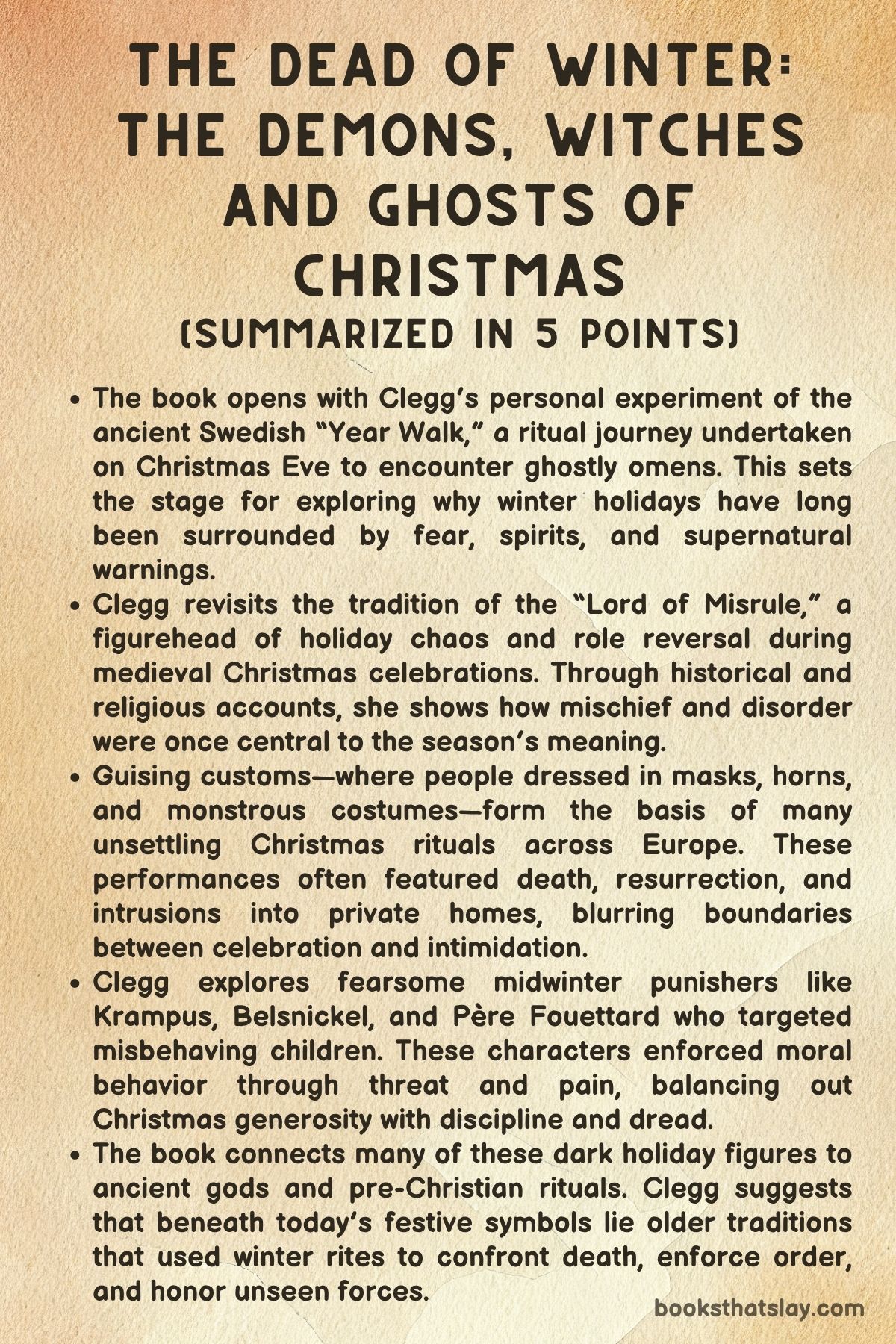

The Dead of Winter by Sarah Clegg is a compelling, historically grounded investigation into the dark and unruly traditions that have long haunted the European midwinter season. Rather than framing winter as a time of quiet reflection and domestic comfort, Clegg explores its wild side—when festivals encouraged chaos, costumes erased identities, and the coldest nights invited monstrous figures, pagan rituals, and the joyous unease of misrule.

Through a deeply researched blend of folklore, anthropology, and cultural history, the book repositions Christmas, Carnival, and the solstice not as static or sanitized traditions, but as dynamic expressions of communal fantasy, fear, and festivity.

Summary

The Dead of Winter opens with a striking account of modern-day Carnival in Venice, placing the reader amid an extravagant masquerade ball. The city is drenched in rain, the ballroom lit with golden grandeur, and the guests don elaborate 18th-century-inspired costumes and ornate masks.

Through this vivid imagery, Sarah Clegg introduces the central theme of the book: the inversion of norms during winter festivities. The mask becomes a symbol of liberation and danger, capable of erasing social boundaries while also granting a disturbing kind of anonymity.

The revelers’ transformation is exhilarating, but it also reveals a more ominous truth—hidden behind masks, people may act out desires and cruelties that society otherwise curtails.

From this modern spectacle, the book traces the origins of misrule to ancient Rome’s Saturnalia festival. Held in December, Saturnalia was a state-sanctioned period of chaos.

Social roles were temporarily inverted—slaves dined like masters, gambling was allowed, and “kings” were chosen by lot only to be mocked. Yet these inversions were not true rebellions; they were tightly managed simulations.

Clegg emphasizes that even during these temporary freedoms, the fundamental power structures remained untouched. The festival was less about genuine liberation and more about reinforcing the status quo by allowing a brief, controlled venting of disorder.

Punishments loomed for those who confused ritual chaos with actual rebellion.

Moving forward in time, Clegg explores how Christian institutions inherited and reshaped these traditions. One striking example is the Feast of Fools, a medieval celebration that brought anarchy into the heart of the Church.

Choirboys could become “Boy Bishops,” and priests dressed in outlandish costumes, sometimes even performing satirical versions of sacred rituals. The Church repeatedly tried to suppress these events due to their irreverent and sometimes dangerous nature.

Despite this, they persisted for centuries, revealing a deeper need in society to play with the sacred and the profane during the darkest time of the year. These rituals made space for both reverence and ridicule, reflecting a spiritual and emotional tension that was never fully resolved.

By the early modern period, winter misrule had entrenched itself in Christmas celebrations, particularly in Britain and parts of Europe. A central figure during this time was the Lord of Misrule, chosen through rituals such as finding a bean in a cake.

Much like the Saturnalian king, he was a symbol of inversion, leading household revelries, parodies, and pranks. However, the rise of Protestantism and the Victorian moral order began to recast Christmas into a holiday of domestic serenity.

Figures like Charles Dickens helped shift its emphasis toward family, charity, and morality. The wilder aspects of the season—drunkenness, mockery, and misrule—were gradually suppressed.

The festive chaos, once central to the winter holidays, was displaced, eventually reemerging in Carnival’s pre-Lenten revelry.

Carnival thus became the last mainstream stronghold of sanctioned chaos. In Venice, its traditions expanded and absorbed the spirit of winter misrule.

Masquerades allowed for fluid identities, cross-dressing, and temporary equalization. Yet beneath the masks, social hierarchies remained intact.

Clegg notes the persistence of troubling imagery—such as blackface—under the guise of festivity, exposing how masking can sometimes shield not only playfulness but prejudice. Carnival’s magic lies in its contradictions: it is enchanting and grotesque, liberating and controlling, festive and threatening.

It exemplifies the tension at the heart of winter celebration—a time when people crave both fantasy and boundaries.

The second essay, “Horse Skulls and Hoodenings,” takes readers deeper into Britain’s folkloric traditions. Clegg brings us to Chepstow, Wales, for a midwinter celebration that fuses the wassailing of apple orchards with the eerie Mari Lwyd procession.

The Mari Lwyd is a skeletal horse-head figure carried under a white sheet by a hidden performer, brought to life with snapping jaws and strange eyes. These ghostly guisers interact playfully and frighteningly with the crowd, continuing an old tradition of door-to-door verse duels where participants had to outwit the Mari party in poetic exchanges to keep them from entering their homes.

The tradition blends horror and humor, showing how midwinter rituals allowed space for both laughter and unease.

Clegg contextualizes this Welsh tradition within a broader European phenomenon. Across the continent, similar costumed figures appear during midwinter festivals, from England’s Hoodening horses to Austria’s Habergeiß and Poland’s Turon.

These beastly guisers typically demand food or perform mischievous acts, striking fear and amusement in equal measure. While their exact origins are obscure, they share common elements: shrouded forms, hinged jaws, and their midwinter timing.

Clegg argues that these traditions reflect not just survival from ancient rituals, but creative reinvention—communities borrowing, adapting, and fusing older elements into new forms, maintaining a living link to a shared cultural past.

The essay also addresses the fusion of two separate practices—apple-tree blessings and door-to-door guising—into hybrid celebrations like the Chepstow Wassail. This blend reflects a broader folkloric trend where customs evolve, overlap, and absorb each other over time.

The essay makes a compelling case for seeing folk tradition not as a static remnant of pagan pasts, but as a vibrant and mutable expression of community identity. This is further supported by comparisons to darker continental figures like Krampus, who punishes naughty children, or witch-like women such as Perchta and Befana, who straddle the line between household protectors and violent enforcers of morality.

In the final essay, Clegg examines the symbolic resonance of winter darkness through a contemporary solstice pilgrimage to Stonehenge. Thousands gather at the ancient site before dawn on 22 December, hoping to witness the sunrise.

While popular belief holds that Stonehenge aligns with the solstice sunrise, archaeological evidence suggests it was more likely oriented to the sunset. The “slaughter stone,” long thought to be tied to human sacrifice, turns out to be colored by algae.

Here, Clegg warns of how modern myth-making often distorts the past. Figures like Jacob Grimm and James Frazer influenced modern views of winter folklore by presenting it as ancient and unchanging, rooted in lost fertility cults and forgotten gods.

Yet their ideas, though largely discredited, continue to enchant because they tell captivating stories.

Clegg critiques this romanticized view of folklore, arguing instead that it is dynamic and invented by ordinary people as much as inherited from ancient tradition. The monsters and rituals of Christmas were more often playful than sacred, their grotesque features designed to thrill, not terrify.

Folklore lives through reinvention, not preservation.

The book concludes with a quiet moment on Christmas night, where the author reflects on how modern audiences are drawn to the darker elements of the season. From Krampus parades to amateur mummers plays, people still seek a touch of misrule amid the holiday’s gentility.

These customs, whether ancient or modern, fulfill a timeless desire: to step briefly into a world turned upside-down, to face darkness with laughter, and to believe, if only for a night, in the magic of chaos.

Characters

The Narrator

At the center of The Dead of Winter is the unnamed narrator, whose voice serves as a reflective, inquisitive guide through layers of folklore, history, and cultural ritual. This character is not merely an observer, but a seeker—someone who physically journeys to ancient and modern sites of winter festivity in a desire to understand the human compulsion toward chaos, inversion, and myth during the darkest days of the year.

In Venice, she wears a mask to experience anonymity and the freedom of Carnival; in Wales, she walks among ghostly Mari Lwyds with equal fascination and unease. She does not claim omniscient authority—her voice is curious, speculative, and often conflicted.

This character embraces the ambiguity of the rituals she describes, acknowledging both the enchantment they offer and the unsettling truths they conceal. At Stonehenge, she joins modern-day pilgrims in celebrating the solstice, all while deconstructing the invented myths that surround it.

Her presence underscores a larger theme of duality: belief versus skepticism, performance versus sincerity, celebration versus suppression. The narrator’s character is ultimately a mirror for the reader, embodying the tension between rational critique and romantic yearning for meaning in tradition.

The Masked Revelers of Venice

The guests at the Venice Carnival, though unnamed, function collectively as symbolic characters within The Dead of Winter. They are embodiments of festive license, their identities obscured by elaborately adorned masks and costumes that evoke the past.

These figures symbolize the spirit of misrule—where the boundaries between class, gender, and identity are deliberately blurred. They perform with abandon, indulging in sensuality, spectacle, and even cruelty, creating an atmosphere that is both alluring and disquieting.

Their anonymity liberates them from social constraints but also strips them of moral accountability. These characters serve as modern echoes of Saturnalian reversal, participating in a tradition that both subverts and reinforces social hierarchies.

They are not individuals but archetypes of human behavior under the veil of disguise—simultaneously liberated and lost.

The Lord of Misrule

The Lord of Misrule is not a single historical person but a recurring figure throughout the cultural history outlined in The Dead of Winter, functioning as an emblem of temporary chaos within structured societies. He emerges as a peasant king during Saturnalia, as a prankster leader during medieval Christmas, and as a mischievous spirit presiding over household celebrations.

This character is symbolic of sanctioned disorder—a person chosen to reign in jest over a time of inversion, leading a world turned upside down. Yet, this figure is always ultimately disposable; his authority is fleeting, and his position often humiliating.

The Lord of Misrule underscores how deeply societies yearn to rebel against norms—if only in structured, time-bound ways. In this sense, he is both a liberator and a pawn, a figurehead of joy and a reminder of constraint.

The Mari Lwyd

The Mari Lwyd is a spectral horse that stalks the wintry streets and orchards of Wales, a folkloric figure brought to life by concealed handlers under white shrouds. In The Dead of Winter, this ghostly beast becomes a character in its own right—part puppet, part spirit, and entirely uncanny.

Its snapping jaws and glittering eyes create an atmosphere that is both festive and frightening, blending humor with horror. The Mari Lwyd tests boundaries between the living and the dead, hospitality and exclusion, tradition and improvisation.

Though it speaks no words, it engages in poetic duels and challenges householders to verbal combat, asserting a kind of power that is at once theatrical and confrontational. The creature’s revived popularity in recent years speaks to a renewed cultural appetite for eerie, embodied folklore.

It is both a relic of the past and a reinvented participant in modern seasonal rites, embodying continuity and transformation.

Krampus, Perchta, and Other Mythic Beasts

These monstrous figures appear as a dark chorus in The Dead of Winter, embodiments of fear, discipline, and supernatural retribution. Krampus, the horned punisher of children in Austria and Bavaria, looms large as a grotesque alternative to the benevolent St.

Nicholas. Perchta, with her dual nature as a household goddess and a brutal disemboweler of lazy children, straddles the line between protector and terror.

These characters are not just boogeymen—they are reflections of societal values, warning figures used to enforce norms through myth and spectacle. Though often presented as ancient, The Dead of Winter challenges their supposed antiquity, suggesting instead that they are creative inventions, shaped and reshaped across generations.

They serve as moral counterweights to festive excess, figures of awe that remind revelers of consequence and control even amid chaos. These characters are deeply theatrical, symbolic of the ways humans use narrative and costume to mediate the darkness of winter—both literal and psychological.

The Druid and Solstice Crowd

At Stonehenge, the narrator encounters a diverse group of spiritual seekers, costumed revelers, and self-proclaimed druids who gather to greet the solstice sun. These individuals function as modern participants in ancient-seeming rites, blending authenticity with performance.

They are not mocked by the text but rather viewed with nuanced affection and curiosity. Their actions—singing, cheering, drumming—form a kind of secular liturgy, celebrating nature, continuity, and community.

At the same time, their role illustrates how folklore is continually being rewritten. The druid figure, in particular, becomes a projection of imagined tradition—born of Victorian revivalism and popular fantasy, rather than archaeological fact.

These characters, then, symbolize the desire to belong to something older and larger than oneself, even if that belonging must be constructed through modern myth-making.

Jacob Grimm and James Frazer

Though not fictional characters, Grimm and Frazer appear in The Dead of Winter as intellectual presences who shaped how generations interpreted seasonal customs. Grimm, with his belief in forgotten goddesses hidden within peasant traditions, and Frazer, with his theories of sacrificial kings, become mythmakers in their own right.

Their characters serve to question the authority of folklore scholarship, highlighting how compelling theories can blur into fantasy when not critically examined. They are depicted as visionaries and fabulists, whose legacies are both rich and problematic.

Through them, the essay examines how academic and literary figures have molded public understanding of tradition—not always in ways supported by fact, but often through the sheer allure of narrative. They represent the power and peril of storytelling itself, and their presence raises questions about who gets to define cultural meaning.

Themes

Misrule and the Illusion of Liberation

The tradition of winter misrule, exemplified through Saturnalia, the Feast of Fools, and Carnival, presents a paradoxical interplay between liberation and constraint. On the surface, these festivities appear to upend social hierarchies, granting slaves power, mocking religious authority, and allowing commoners to masquerade as kings.

Yet beneath this playful inversion lies a rigid boundary demarcating true power. The temporary freedoms granted during misrule do not dismantle established hierarchies; they reinforce them by making their restoration seem natural and necessary.

In The Dead of Winter, the depiction of masked balls in Venice and mock kings of Saturnalia illustrates how these rituals offered performative license without actual transformation. The permission to play at subversion was always contingent upon returning to normalcy.

The consequences of forgetting this boundary could be severe, particularly for the lower classes. This theme underscores how systems of control co-opt even rebellion, shaping how people express and contain their desire for freedom.

Masking, role reversal, and mock rituals create the illusion of autonomy, yet they depend on and reaffirm the structures they momentarily ridicule. In this sense, misrule becomes less an escape and more a valve—venting discontent without threatening the machinery of power.

Ritual, Performance, and Cultural Continuity

Festive rites across Europe, particularly those involving guising and animal symbolism, reveal the deeply performative nature of winter traditions. These performances are not merely entertainment; they are vessels of cultural transmission that sustain memory, identity, and communal bonds.

The Mari Lwyd, with its snapping horse skull and rhyming duels, encapsulates how ritual performance fuses the uncanny with the communal. In The Dead of Winter, these traditions are shown not as static relics of the past but as living practices that adapt and persist.

The hybridization of door-to-door wassailing with orchard-centered blessings in Chepstow exemplifies this dynamism, demonstrating how rituals morph to suit new social realities while preserving their mythic cores. Performance allows ancient symbols—whether in the form of ghostly horses, grotesque masks, or chanting verses—to re-emerge in new settings, binding communities through shared acts.

Even in their contemporary forms, these spectacles retain a resonance that transcends their origins, linking present-day revelers to ancestors who also sang into the darkness and laughed at their fears. This continuity does not mean stasis but rather a constantly negotiated connection between past and present, where tradition is as much invention as inheritance.

The Ethics and Ambiguities of Anonymity

Masquerade plays a central role in winter festivities, offering both freedom and danger. In Venice’s Carnival, the mask becomes a double-edged tool—liberating individuals from the gaze of society while also severing them from accountability.

As described in The Dead of Winter, masked revelers engage in acts that blur the line between celebration and transgression, protected by anonymity. This protective shroud can foster creativity and joy but can also mask cruelty, prejudice, or moral indifference.

The presence of offensive symbolism, such as blackface, beneath the guise of play demonstrates how cultural amnesia or indifference can be enabled by disguise. The mask does not erase identity; it conceals it just enough to allow hidden impulses to surface without consequence.

This dynamic introduces a moral ambiguity that challenges the celebratory tone of misrule. The festive license to be someone else can easily become the license to do harm, all under the pretense of revelry.

In this context, anonymity is not merely a neutral absence of identity but a condition that magnifies the ethical stakes of participation. The mask allows for both delight and disavowal, forcing a reckoning with the costs of liberation without responsibility.

Folklore, Fantasy, and the Invention of the Past

One of the most compelling themes in The Dead of Winter is the seductive power of imagined history. The essay’s exploration of Stonehenge, Grimm, and Frazer illustrates how the human desire for enchantment often overrides historical fact.

The modern pilgrimage to Stonehenge on the winter solstice, while emotionally powerful, misinterprets archaeological evidence—privileging sunrise over sunset, ritual sacrifice over architectural complexity. Similarly, Grimm and Frazer projected their own fantasies onto folk traditions, casting them as fragments of forgotten religious systems or fertility cults.

These imaginative reconstructions persist because they offer coherence, drama, and meaning in a chaotic world. Yet the essay warns that such projections can be distorting.

They deny the agency of the people who created and adapted these customs, portraying them as passive vessels rather than inventive participants. The romanticization of folklore transforms dynamic practices into static echoes, ignoring the creativity and adaptability that define living traditions.

By highlighting these distortions, the text invites a more nuanced appreciation of folklore—not as ancient truth, but as a collective, evolving narrative that reflects both past and present desires. The fantasy of an unbroken link to ancient rituals may be false, but the longing that creates such fantasies is real, rooted in a deep cultural need for continuity and myth.

Darkness, Fear, and the Pleasures of the Grotesque

The enduring appeal of winter customs often lies in their embrace of the grotesque and the terrifying. Whether through Krampus’s monstrous punishment, the eerie antics of Mari Lwyd, or the chaotic imagery of Carnival, The Dead of Winter demonstrates that fear is an integral part of festive pleasure.

These customs allow communities to stage and contain their darkest impulses—violence, disorder, taboo—within the safe boundaries of ritual. The grotesque becomes a source of laughter, bonding, and even moral instruction.

Children are frightened to behave; adults are reminded of mortality and transience. The grotesque does not simply shock—it instructs and delights.

Modern resurgences of these customs, from Krampus runs to revived mummers plays, show a hunger for emotional intensity in a culture that often prizes sanitized, commercialized holidays. The blend of horror and humor, shadow and light, offers a fuller range of emotional experience than the serene nativity scene or glittering Christmas tree.

In embracing the monstrous, these traditions affirm the complexity of the human psyche and the value of catharsis. They remind us that darkness has its place in celebration, not as a threat, but as a necessary counterbalance to joy.

The grotesque is not an aberration but a mirror—a way of confronting our fears and laughing back.