The Devil’s Pawn Summary, Characters and Themes

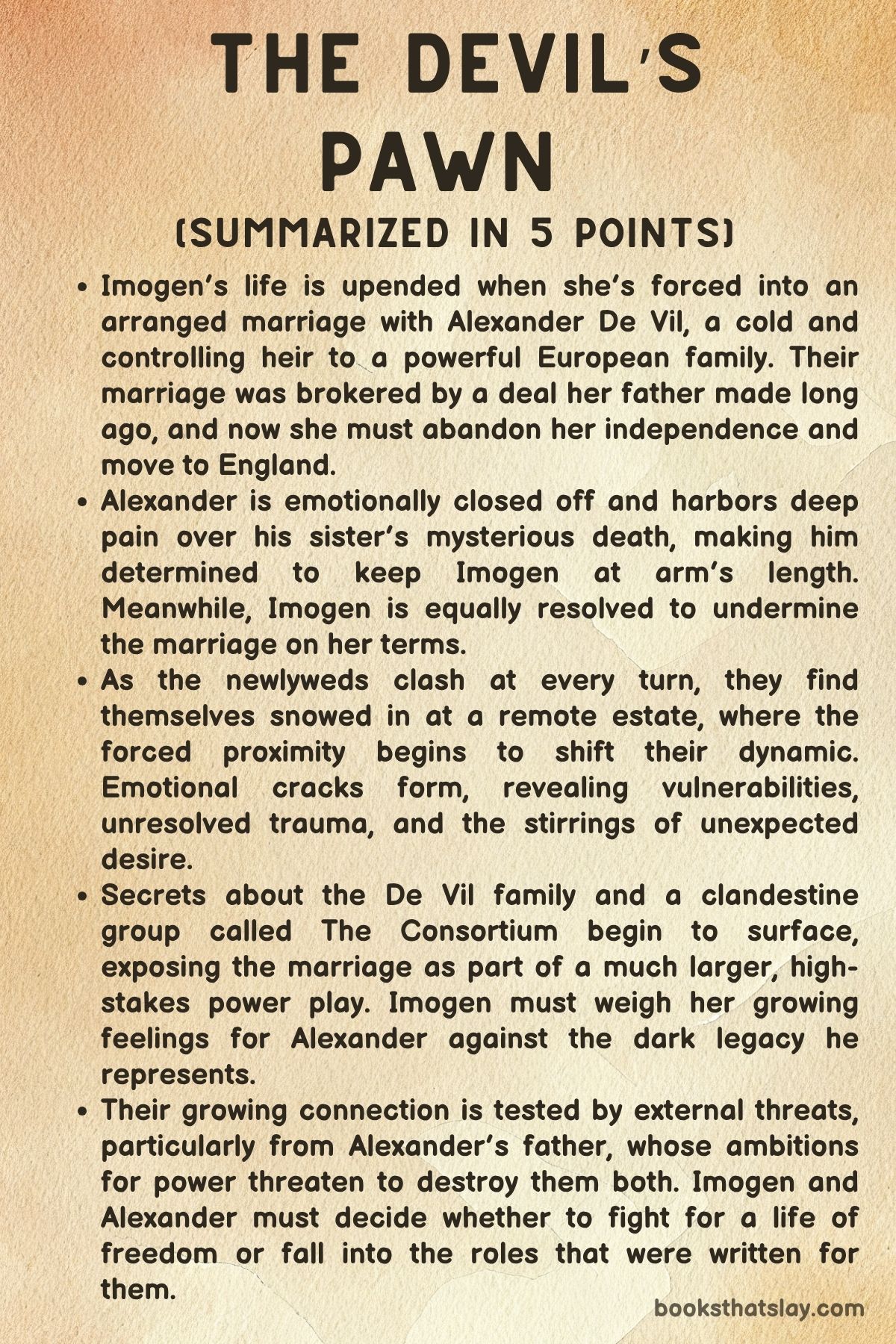

The Devil’s Pawn by Tracie Delaney is a dark romance novel that unpacks the tension and emotional upheaval of an arranged marriage between two people trapped by family obligations. At its center is Imogen Salinger, a recent graduate forced into marrying Alexander De Vil, the cold and emotionally barricaded heir of a powerful dynasty.

Bound by contracts made before her birth, Imogen must navigate a world of wealth, power, and psychological warfare while trying to preserve her independence. The book focuses on themes of autonomy, trauma, and transformation, charting a turbulent path from resentment to love between two people who never chose each other—but might just choose to stay.

Summary

Imogen Salinger’s arrival at Oakleigh Hall marks the beginning of a forced chapter in her life. Although the mansion is grand, it feels more like a prison.

Her father signed a contract years ago that now forces her into marriage with Alexander De Vil. Despite a promising job offer and dreams of becoming an architect, Imogen is required to sacrifice her future for a business alliance.

Her first encounters with Alexander are cold and antagonistic. He’s as reluctant as she is, but for different reasons.

Alexander views the arrangement as a political move to protect his family’s standing in The Consortium, a shadowy global alliance. He’s determined to manipulate Imogen into asking for a divorce, hoping to maintain the appearance of obedience while avoiding genuine commitment.

Their interactions bristle with hostility, yet under the surface is an emotional charge neither is willing to admit. Imogen finds solace in Alexander’s sister, Saskia, who becomes a rare source of kindness.

Despite the cruelty of the situation, Saskia encourages Imogen to embrace hobbies and hold on to her sense of self. On their wedding day, Imogen is a reluctant bride in a lavish ceremony.

Alexander surprises her with a passionate kiss, only to dismiss it as meaningless. This cruelty sets the tone for their early married life, with Alexander determined to emotionally isolate her while avoiding intimacy.

Imogen’s journey into this new world continues without a honeymoon, reinforcing her emotional distance from Alexander. Her dreams of going to Scotland are shattered when he refuses to take her.

However, her father-in-law Charles provides a moment of warmth, hinting that Alexander’s decisions may be more emotionally complex than they appear. The wedding night becomes a psychological battlefield, with Alexander gifting her a new phone to control her communication and refusing to consummate the marriage.

Their confrontation in the library is intense and confusing for Imogen, awakening feelings she neither trusts nor wants.

Their brief honeymoon at Thistlewood introduces a subtle shift. Through a metaphorical game of chess, Alexander begins to see Imogen not as a pawn but as a capable equal.

These interactions allow flickers of curiosity and mutual respect to emerge. However, back at Oakleigh, tensions rise again.

When Imogen misses a family dinner, Alexander retaliates by humiliating her in front of everyone. In response, she maxes out his credit card on charitable donations.

Their war escalates, blending anger, emotional volatility, and reluctant fascination. They begin to see the cracks in each other’s armor but continue resisting any form of surrender.

Imogen’s growing emotional vulnerability is heightened when Alexander forces the dismissal of a stable worker she confided in. With no one to trust, her isolation deepens.

Her best friend Emma cannot visit, and Imogen is further drawn into the emotional web spun by Alexander’s cold cruelty and rare moments of care. One night, after finding him asleep, she waxes off one of his eyebrows as payback.

His revenge is severe—he traps her in the estate’s panic room for hours, a calculated move meant to frighten and punish her. Yet, when he comforts her afterward, the line between control and care becomes more blurred.

Imogen tries to escape to California but is stopped by Alexander, who controls her passport and freedom. Their power struggle seems unending until Emma unexpectedly arrives.

Her presence lightens Imogen’s world, but Alexander’s final revenge is brutal: he deports Emma back to the U. S.

without warning. This act devastates Imogen and forces Alexander to confront the emotional wreckage his manipulation has caused.

His internal conflict grows, caught between wanting to push Imogen away and his increasing obsession with her.

Later in the book, Imogen is kidnapped, and her survival forces an emotional breakthrough. She wakes in Alexander’s arms, only to be devastated again when he confesses to injecting her with birth control and implanting a tracker.

Though motivated by fear for her safety, his violations of trust shatter their fragile bond. Imogen demands the tracker’s removal and returns to California with Saskia’s help.

Alexander follows, ready to make amends not through apologies but through actions that show he’s changed.

In California, the couple wrestles with opposing desires—Imogen wants children; Alexander doesn’t. When he implants a tracker in himself as a gesture of equality, Imogen is moved.

She agrees to return to England, not because she’s submitting, but because she loves him and hopes he’ll eventually open up to the idea of a family. Their reunion marks the beginning of a more mature, transparent relationship.

Back at Oakleigh, things seem to settle. Imogen gets a horse for her birthday and starts her dream job at Zenith.

However, a snow globe with a hidden key hints at unresolved secrets surrounding Alexander’s mother and sister’s deaths. Meanwhile, their physical relationship matures, marked by scenes of mutual trust and intimacy rather than earlier power games.

A surprise pregnancy changes everything. Despite supposed birth control, Imogen learns she’s expecting.

Alexander spirals into panic, and they discover the contraceptive was a placebo—his father’s manipulation to ensure an heir. Alexander, who once violated Imogen’s autonomy under the guise of protection, now feels that same betrayal from his own father.

At the family graves, he confronts his trauma, acknowledges his love for Imogen, and fully commits to their future, including fatherhood.

The final chapter shifts perspective to Nicholas, Alexander’s cousin, whose quiet fiancée Elizabeth is suddenly killed in a car explosion. The shock sets the stage for another mystery and hints that the De Vil family’s secrets are far from over.

The novel closes not with a fairy tale ending but with the promise of transformation—two people who began as enemies are now partners, bound not by duty but by choice, having fought their way to love through fire, manipulation, vulnerability, and eventually, truth.

Characters

Imogen Salinger

Imogen Salinger stands as the emotional heart of The Devil’s Pawn, a young woman thrust into a life she did not choose and determined to reclaim her agency against a backdrop of wealth, control, and manipulation. At twenty-one, she arrives at Oakleigh Hall not as a bride-to-be but as a prisoner of circumstance, forced into marriage with Alexander De Vil as part of a business transaction forged by her father before her birth.

Her initial characterization is steeped in resistance; Imogen is sharp-tongued, defiant, and unwilling to succumb quietly to the life laid out for her. This fiery resolve anchors her throughout the novel as she navigates a deeply complex and often toxic relationship with Alexander.

Despite being emotionally wounded by his cruelty and manipulation, she never abandons her sense of self. Instead, she wages a quiet rebellion—teasing, provoking, and asserting control wherever she can, even if only in small acts of defiance.

As the narrative unfolds, Imogen’s character evolves from reactive to strategic. Her goal shifts from escape to understanding, and eventually, to transformation—not just of herself, but of the man she’s forced to live with.

She becomes a mirror for Alexander, both exposing his flaws and igniting his humanity. Her compassion, shown even in moments of profound betrayal, such as when she tends to Alexander’s injured hand, illustrates a depth of empathy that ultimately reshapes their relationship.

Yet, Imogen is no doormat. She consistently demands respect and autonomy, especially in critical moments—whether confronting Alexander for locking her in a panic room or walking away from him after discovering he violated her consent by injecting her with birth control.

Her strength lies not in physical power but in emotional endurance, intellectual agility, and moral clarity. By the end of the novel, Imogen emerges as a woman no longer defined by others’ expectations, but by her capacity to love without losing herself.

Alexander De Vil

Alexander De Vil is both antagonist and love interest, a character defined by internal conflict and a legacy of trauma. At first glance, he is cold, calculating, and emotionally unreachable—a man who has accepted duty over desire and uses control as his coping mechanism.

His initial plan to manipulate Imogen into leaving him positions him as a villain cloaked in charm and privilege. However, beneath this exterior lies a man profoundly damaged by the past: the abduction and death of his sister Annabel, the grief of losing his mother, and the suffocating expectations of The Consortium.

These buried traumas manifest in his aversion to emotional vulnerability, particularly his refusal to have children and his obsessive need to maintain control, even at the expense of Imogen’s autonomy.

Throughout The Devil’s Pawn, Alexander undergoes a slow, painful metamorphosis. His cruelty is not without conscience, and moments of regret frequently pierce through his armor.

His complex feelings for Imogen evolve from irritation to fascination, to something resembling love—though he does not initially understand it as such. The turning point in his character comes when he is forced to confront the consequences of his actions, particularly when Imogen leaves him after discovering his manipulations.

Alexander’s decision to inject himself with a tracker as a gesture of equality marks a significant emotional shift, signifying his willingness to meet Imogen on her terms. By the end, his apology at the family gravesite and acceptance of impending fatherhood represent not just reconciliation, but rebirth.

Alexander is a man slowly unlearning the notion that love is weakness and discovering instead that vulnerability, when shared, is transformative.

Saskia De Vil

Saskia serves as the bridge between two emotionally armored characters, offering warmth and empathy in a house otherwise steeped in power games and emotional repression. As Alexander’s sister, she provides a sharp contrast to her brother’s aloofness.

She befriends Imogen early on, becoming her confidante and emotional anchor. Saskia’s easy charm, her encouragement for Imogen to take up hobbies, and her gentle insights offer moments of respite from the otherwise high-stakes psychological warfare taking place between Imogen and Alexander.

Yet Saskia is not merely a narrative device; she too has suffered under the rigid structure of their world, and her quiet rebellion is expressed through compassion rather than confrontation.

Her greatest contribution to the narrative comes in the form of support and subtle wisdom. She facilitates Imogen’s temporary escape to California, recognizing the importance of agency in healing fractured trust.

Saskia understands both her brother and his wife better than they understand themselves, and though she doesn’t force change, she quietly creates space for it. In a world of deception and dominance, Saskia’s presence is an act of emotional honesty—small, steady, and profoundly necessary.

Charles De Vil

Charles is initially introduced as the patriarch of the De Vil family and seems, at first, to be a man cast in the same mold as his son—strategic, dominant, and consumed with maintaining control through alliances like The Consortium. Yet as the story progresses, he reveals a surprising degree of nuance.

His conversation with Imogen at the wedding—where he assures her Alexander chose this path—sows early seeds of doubt about his true nature. Charles functions as both the architect of much of Alexander’s trauma and a man capable of measured kindness.

His decision to order the placebo birth control, thereby circumventing his son’s autonomy in order to secure a grandchild, exemplifies his overarching strategy: legacy above all.

Still, Charles is not portrayed as a one-dimensional villain. He possesses the charisma and wisdom of someone who has survived and thrived within an unyielding power structure.

In many ways, he serves as a cautionary figure for Alexander—a glimpse into a possible future devoid of emotional connection, governed only by duty and legacy. Charles’s influence looms large throughout the novel, acting as both a threat and a twisted form of mentor.

His actions have lasting repercussions, but his motivations are never entirely malicious; rather, they are the byproduct of a world where control and inheritance are currency.

Emma

Emma, Imogen’s best friend from California, plays a relatively small but emotionally vital role in the narrative. She embodies the world Imogen left behind and serves as a tether to her former identity.

Emma is witty, grounded, and fiercely loyal—offering comic relief, emotional validation, and a sharp outside perspective on the world Imogen has been forced into. Her brief presence injects warmth and freedom into Imogen’s otherwise claustrophobic existence at Oakleigh.

When she’s forcibly removed by Alexander, the event marks a moral nadir in his character arc and crystallizes for Imogen the depth of his manipulations.

Emma also serves as a symbolic barometer of Imogen’s autonomy. Her initial absence deepens Imogen’s isolation, while her reappearance rejuvenates her spirit.

That Alexander chooses to exile her underscores how threatening emotional connections are to the controlled environment he has built. Ultimately, Emma’s role, though limited in duration, is deeply impactful—highlighting themes of loyalty, friendship, and personal freedom amidst systemic control.

Nicholas

Nicholas is a shadowy yet increasingly important presence in The Devil’s Pawn, acting as both a foil to Alexander and a setup for the next book’s emotional stakes. He appears early on as a mysterious family figure, but his significance grows as he reveals more about Alexander’s insomnia and past.

Nicholas is observant, emotionally aware, and capable of profound empathy. His dynamic with Elizabeth, and the tragic twist at the novel’s end—her abduction and the explosion—introduce a parallel emotional arc to that of Alexander and Imogen’s.

The implication is clear: Nicholas’s journey is just beginning, one marked by vengeance, grief, and the unraveling of more De Vil family secrets.

He represents the next evolution in the De Vil family’s generational trauma. Where Alexander is learning to heal, Nicholas is poised on the edge of violence and retribution.

His arc promises to explore how grief transforms not just individuals, but entire legacies. His emotional intelligence, previously used for support and insight, may well become a weapon in the sequel.

Elizabeth

Elizabeth remains a peripheral yet poignant figure, present mostly in the shadow of Nicholas’s storyline. Quiet, unassuming, and not fully fleshed out in this installment, she nonetheless represents a fragile hope in a world dominated by political marriages and emotional manipulation.

Her sudden disappearance and presumed death in the car explosion are shocking and tragic, upending not only Nicholas’s world but also shaking the foundation of what little normalcy remains in the De Vil dynasty. Though little is known about her, Elizabeth’s role becomes symbolically potent—serving as the latest casualty in a legacy built on power, secrecy, and control.

Her death marks a violent end to the book, setting the tone for a darker, more explosive sequel.

Themes

Bodily Autonomy and Control

Throughout The Devil’s Pawn, the theme of bodily autonomy is persistently challenged, questioned, and reclaimed, particularly through the experiences of Imogen. Her body is not her own from the very start—her future, her marriage, and even her movements are dictated by a contract signed before she was born.

This erasure of her agency is not only legal and familial but becomes intensely physical, especially as Alexander enforces control over her reproductive rights and physical safety without consent. The clandestine injection of birth control and the implantation of a tracker epitomize the invasive power imbalance at play.

These actions, rooted in Alexander’s past trauma and his misguided need to protect, shatter the delicate trust Imogen was beginning to build with him. For Imogen, the realization that even the most intimate decisions about her body were made by others is a devastating betrayal.

Yet the trajectory of her character bends toward reclamation. Her fury, her demands for removal of the tracker, and her insistence on space signal her active resistance.

She no longer accepts passivity or the role of a pawn. Even her eventual return to Alexander is not a concession but a conscious choice—made on her own terms.

Her pregnancy becomes both a symbol and a test of this regained agency. Though it was the result of yet another violation—this time from Alexander’s father—her decision to keep the child marks a defining moment where autonomy is no longer just fought for, but finally exercised.

The novel paints bodily autonomy not merely as a theme, but as a battleground, a site of resistance, and ultimately, a core component of personhood and dignity.

Power, Rebellion, and Psychological Warfare

The power dynamics between Imogen and Alexander are an ever-shifting storm. Both are caught in a high-stakes arrangement that neither desires, and rather than accept their fate with submission, they weaponize rebellion and manipulation in calculated games of psychological warfare.

Imogen resists her confinement through subversive actions—mocking Alexander, maxing out his credit card for charitable donations, waxing off his eyebrow in retaliation—all while cultivating a deceptive civility to gain his trust. Her rebellion is layered, functioning not just as resistance but as a strategic attempt to secure freedom.

Alexander, meanwhile, orchestrates his own counteroffensives. Locking her in a panic room, monitoring her communications, and manipulating situations to isolate her from allies like Emma all reflect a disturbing mastery of control, rooted in his belief that emotional detachment equates to strength.

Yet this war is not without collateral. Both characters are emotionally destabilized by their own actions.

Their confrontations alternate between cruelty and vulnerability, sarcasm and yearning, punishment and tenderness. What begins as antagonism increasingly exposes deep-seated emotional wounds—Alexander’s rooted in childhood trauma, Imogen’s in the violation of choice.

The chess games they play are emblematic of their reality: strategic, risky, and designed to test boundaries. But unlike the game, their war doesn’t end with a clear victor.

Instead, it evolves into a realization that control, when used to dominate rather than protect, leads only to mutual destruction. In recognizing this, their psychological warfare begins to subside, replaced by a more honest reckoning with the past and a tentative move toward partnership.

Trauma and the Inheritance of Pain

Alexander’s character is profoundly shaped by past trauma, and the novel traces how unprocessed pain can calcify into fear, cruelty, and dysfunction. The murder of his mother and the abduction of his sister have carved deep psychological wounds, leaving him emotionally paralyzed and resistant to vulnerability.

His avoidance of parenthood, obsession with control, and deep distrust of emotional intimacy stem from these unresolved experiences. This inheritance of pain manifests not only in his behavior but in the environment around him—Oakleigh Hall is less a home than a fortress, a mausoleum haunted by grief.

His father, Charles, represents another generation of trauma transmission. Though more affable on the surface, Charles manipulates both Alexander and Imogen with chilling calmness, evidenced most powerfully in the revelation that he substituted Alexander’s injection with a placebo, orchestrating the conception of a child.

Pain, in this world, is not private—it is passed down, institutionalized, and disguised as duty or protection. Imogen becomes both witness and participant in this inherited suffering.

Her growing understanding of Alexander’s past allows her to connect with him not as a victimizer, but as someone struggling under a burden he doesn’t know how to relinquish. The turning point occurs at the family gravesite, where Alexander finally names his grief, confronts his guilt, and allows himself to want a future unshackled from the past.

This moment of reckoning does not erase trauma, but it marks the beginning of healing. The novel insists that while pain may be inherited, it doesn’t have to define one’s future.

Acknowledgment, vulnerability, and connection can break the cycle.

Marriage as a Battleground of Identity

In The Devil’s Pawn, marriage is not portrayed as a union of love and mutual respect, but as a crucible in which individual identity is tested, fragmented, and ultimately redefined. For Imogen, marriage threatens the erasure of her aspirations, autonomy, and voice.

It becomes the symbol of every societal expectation she was raised to internalize yet intuitively rejects. Trained to be an architect, she’s instead cast into a role that demands obedience and sacrifice.

Her initial resistance is instinctual—refusing to embrace traditions, defying Alexander’s rules, and insisting on the right to her own body and choices. But over time, her identity shifts not through surrender, but through reassertion.

She learns to redefine what it means to be a wife—not as a subordinate but as an equal with her own terms. Alexander’s transformation mirrors hers, though with different stakes.

Marriage for him is a strategy, a political necessity orchestrated by the Consortium. He approaches it as a problem to solve, a mechanism to protect legacy and status.

Yet his interactions with Imogen force a reckoning: emotional connection and vulnerability cannot be ruled or coerced. The journey from adversarial spouses to willing partners is one of identity reconstruction.

Each must decide whether marriage will consume them or become a space where individual agency can coexist with shared purpose. The result is a nuanced portrait of modern marriage—one where love is earned, not given; where identity is preserved, not dissolved; and where partnership is reimagined as a choice rather than a constraint.

The Illusion of Protection

Throughout the novel, Alexander repeatedly insists that his controlling actions are acts of protection. From the birth control injection to the surveillance to the isolation from external allies, every boundary he crosses is justified by a fear of losing Imogen to a dangerous world.

But this supposed protection is a smokescreen, masking his inability to trust or relinquish control. The panic room episode exemplifies this illusion: what he labels as a lesson in safety becomes an act of emotional cruelty.

Similarly, the tracking device, while born from trauma, reinforces a dynamic of surveillance and domination. For Imogen, this protection feels indistinguishable from imprisonment.

Her frustration lies not only in the actions themselves but in their paternalistic logic—decisions made for her own good, without her voice or consent. Yet the novel complicates this binary.

Alexander is not a cartoonish villain but a man unraveling under the weight of his fear. His need to protect is genuine, if misguided, and rooted in unresolved trauma.

Only when he begins to understand that real protection means trust—not control—does their relationship begin to shift. This is most clearly seen in his symbolic act of implanting a tracker in himself, an attempt to level the imbalance and take responsibility.

Still, it’s not the gesture alone that signals growth, but the recognition that safety cannot come at the cost of autonomy. The illusion of protection is dismantled only when both characters accept that love requires risk, vulnerability, and the mutual respect of boundaries.

Protection, the novel argues, must never come at the price of freedom.