The Divine Comedy Summary, Characters and Themes

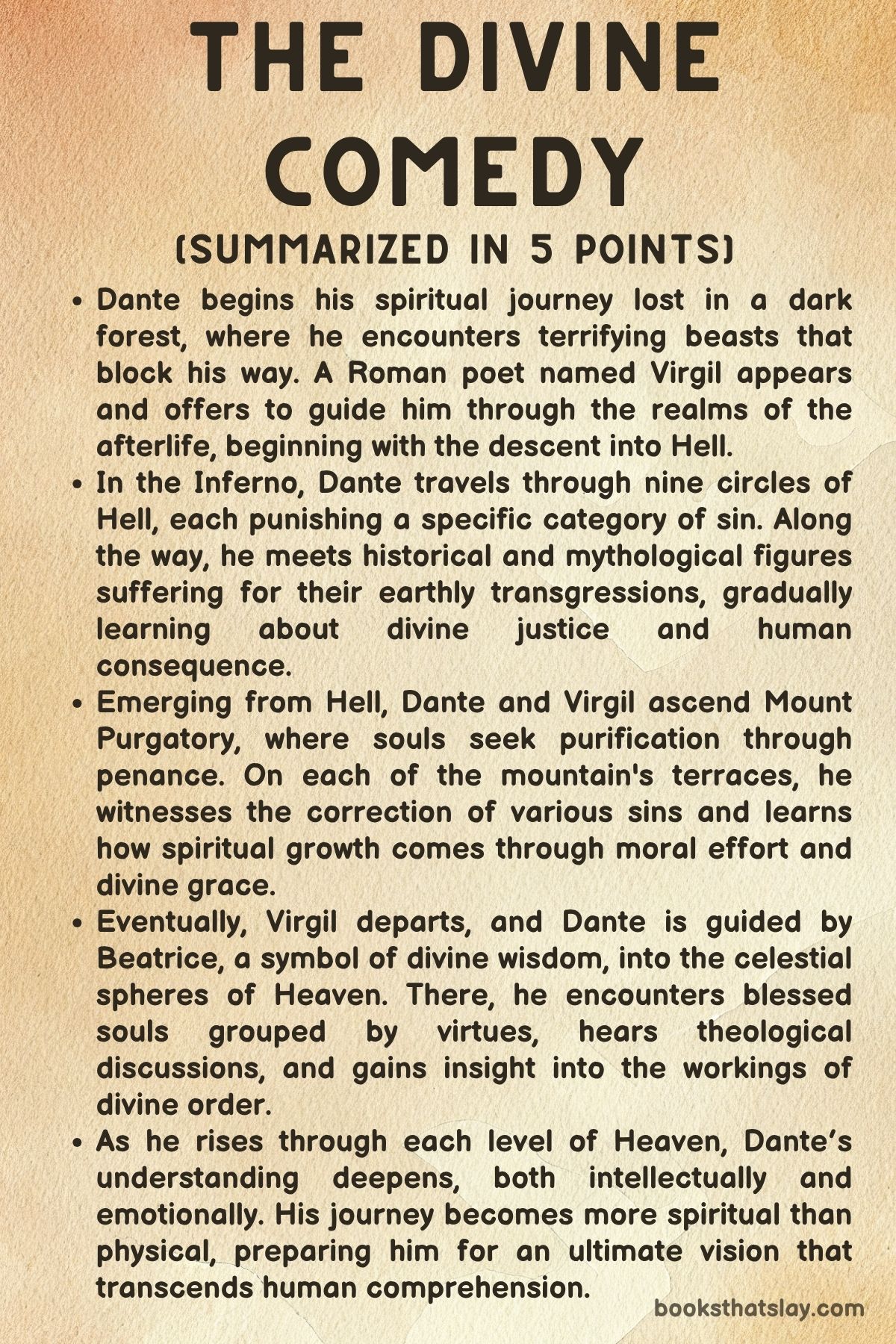

The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri is one of the most influential works in Western literature. Composed in the early 14th century, it charts the soul’s journey toward God, structured as a spiritual pilgrimage through the realms of the afterlife: Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise.

Written in terza rima and rich with allegory, theology, and political commentary, the poem reflects Dante’s personal exile, philosophical insights, and religious convictions. At its heart, it is both an intensely personal reflection on sin, justice, and redemption, and a grand cosmological vision of divine order. The work is guided by poetic figures like Virgil and Beatrice, each representing facets of reason and divine grace.

Summary

The Divine Comedy opens in a dark wood where Dante, representing the everyman soul, finds himself spiritually lost midway through his life. Attempting to climb a sunlit hill, he is repelled by three beasts—a leopard, a lion, and a she-wolf—representing different categories of sin.

At this point of despair, he is met by the Roman poet Virgil, who has been sent by Beatrice, Dante’s beloved and the symbol of divine love. Virgil explains that Dante must journey through Hell and Purgatory before he can reach Paradise.

Dante consents and begins his journey.

They arrive at the gates of Hell, marked with the infamous words: “Abandon all hope ye who enter here. ” Just beyond lies the vestibule, home to the Opportunists—those who in life committed to nothing and now chase a blank banner for eternity.

After crossing the river Acheron, they descend into the First Circle: Limbo. Here, unbaptized virtuous pagans reside in sorrowful peace, lacking hope of salvation.

Dante meets Homer, Ovid, and other great thinkers, who honor him with inclusion in their circle, but the absence of divine light highlights the limitations of human wisdom without grace.

In the Second Circle, they encounter Minos, who judges the damned. Here, the lustful are whipped in a ceaseless storm, symbolic of their lack of control in life.

Dante speaks with Francesca da Rimini, whose tragic love for her brother-in-law Paolo leads him to faint in pity. In the Third Circle, gluttons wallow in foul slush under relentless rain, tormented by Cerberus.

The Florentine soul Ciacco foretells future political chaos in their home city.

Circle Four holds the Hoarders and Wasters, endlessly crashing great weights against one another in a futile cycle. Their lack of moderation in life leaves them blind and unrecognizable.

In the Fifth Circle, they pass the Styx, where the wrathful fight above the surface and the sullen remain submerged in slime. Dante meets a political enemy, Filippo Argenti, and reacts with righteous indignation.

Virgil commends his reaction as appropriate spiritual maturity.

At the gates of Dis, the infernal city that separates Upper Hell from Lower Hell, fallen angels refuse entry to the poets. A divine messenger arrives, disperses the resistance, and opens the gate.

Within, heretics lie in fiery tombs for denying the soul’s immortality, emphasizing the consequences of spiritual arrogance. Beyond this, Dante witnesses the punishments of the violent, fraudulent, and treacherous—sins with more profound malice and separation from divine will.

In Purgatorio, Dante begins his climb up the mountain of moral renewal. After passing through the gates of Purgatory, he journeys through a series of terraces or cornices where souls purge the seven deadly sins.

On the Fourth Cornice, the Slothful race tirelessly to make amends for their former laziness. Here, Virgil discusses the nature of love—its origins, functions, and misdirections—and how it must be governed by reason and divine revelation.

Dante dreams of a Siren transformed into beauty before being unmasked by a heavenly lady, symbolizing worldly temptation and the need for spiritual clarity.

On the Fifth Cornice, the avaricious and prodigal lie face-down, repenting for excessive attachment to material wealth. Pope Adrian V emphasizes humility and prayer.

Dante also meets Hugh Capet, who condemns his dynasty’s greed and prophesies future corruption in France and the Church. As Hugh speaks, a quake rocks the mountain, announcing a soul’s completed purgation.

This is explained in the next canto when they meet Statius, a Roman poet secretly converted to Christianity through Virgil’s writings. His hidden faith condemned him to punishment for spiritual lukewarmness, but his joy at seeing Virgil is overwhelming.

In the Sixth Cornice, gluttons suffer hunger and thirst beneath a tree whose fruit they cannot reach. Examples of temperance—Mary, Daniel, John the Baptist—are extolled.

Among the emaciated souls is Forese Donati, Dante’s friend, who attributes his rapid purification to his wife’s prayers. Their conversation reflects the power of piety and contrasts the moral decadence of Florence’s current women with the virtue of Forese’s wife.

The journey reaches its culmination in Paradiso, where Dante ascends through successive spheres of Heaven, guided now by Beatrice. In the highest of the heavenly spheres, the Primum Mobile, he sees the celestial mechanics powered by God’s love.

From here, he glimpses the concentric angelic choirs moving with increasing intensity the closer they are to the divine center. Beatrice explains that the divine order governs both the physical cosmos and spiritual reality.

Dante learns of the hierarchy of angels—Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, and others—each with a distinct role in divine governance.

Entering the Empyrean, Dante encounters the Mystic Rose, a celestial garden where the blessed are arranged by love and grace. Souls glow in communion with God while angels move between the Rose and the divine light.

Beatrice, now beyond description, returns to her celestial place. St.

Bernard assumes the role of guide, showing Dante the seats of Mary, John the Baptist, and the children who died young. The precise order of souls confirms the perfection of divine justice.

Finally, Bernard prays to the Virgin Mary to grant Dante the vision of God. The prayer is answered.

Dante beholds a triune image: three circles of light, representing the Trinity. In one, he sees the image of Christ—humanity mirrored within divinity.

Though he cannot fully comprehend the mystery, his intellect and will are suddenly aligned in harmony with divine love. The poem concludes with Dante’s soul moved by the force that drives all existence—“the Love that moves the sun and the other stars.

The Divine Comedy is not just a narrative of the afterlife, but a symbolic journey of the soul, from confusion and sin through purification and enlightenment, ending in the union with divine truth. It affirms that while reason may guide, only divine love completes the journey.

Characters

Dante

Dante, the protagonist and pilgrim of The Divine Comedy, serves as both the central character and a representative of humanity’s spiritual journey. At the beginning of Inferno, Dante is in a state of moral and spiritual disarray, symbolized by his being lost in a dark wood.

This marks his estrangement from the righteous path. His journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise represents not just an individual quest for salvation but also a universal one, where the soul must recognize sin, undergo repentance, and ultimately reach divine grace.

Dante’s character evolves from a man overwhelmed by fear and pity to one gaining moral clarity and resolve. His encounters with the damned deepen his understanding of justice, personal responsibility, and divine law.

In Purgatorio, he becomes more introspective and philosophical, contemplating love, free will, and grace. His progress is marked by increasing spiritual maturity and detachment from earthly distractions.

By Paradiso, Dante becomes a vessel for divine truth, experiencing mystical union and receiving glimpses of celestial order and divine presence. His character culminates in a moment of sublime harmony, where his will is fully aligned with divine love, showing his complete transformation.

Virgil

Virgil, the Roman poet, is Dante’s guide through Hell and Purgatory and represents Human Reason. Calm, wise, and authoritative, Virgil is instrumental in initiating Dante’s journey, rescuing him from despair and guiding him past the initial beasts that block his path.

His role reflects the belief that reason can identify and analyze sin but cannot provide salvation. In Inferno, he interprets the horrors of Hell, explaining the logic behind divine justice and moral consequences.

His limitations are made clear when they reach the gates of Dis, which he cannot open without heavenly intervention, underscoring the insufficiency of reason alone in transcending evil. In Purgatorio, he deepens his philosophical role, especially in his discussions of love, will, and virtue.

Though he inspires awe and devotion in Dante, he remains emotionally restrained and bound to the confines of reason. His departure at the end of Purgatorio is poignant—an emblem of reason yielding to divine revelation, embodied in Beatrice.

Despite not entering Paradise himself, Virgil’s presence is foundational, illustrating that rationality is essential but not the ultimate path to salvation.

Beatrice

Beatrice, though largely absent until Paradiso, exerts a powerful influence throughout The Divine Comedy. She embodies Divine Love and Revelation, contrasting with Virgil’s representation of reason.

Beatrice’s compassion is the catalyst for Dante’s journey; she descends into Hell to enlist Virgil’s help, demonstrating her spiritual authority and heavenly concern. In Paradiso, she replaces Virgil and guides Dante through the celestial spheres.

Her presence overwhelms Dante with awe, as her beauty grows in radiance the closer they get to God—symbolizing increasing divine enlightenment. Beatrice serves not only as a guide but also as a spiritual teacher who challenges Dante to rise above earthly thinking.

She criticizes flawed theology and corrupt clergy, calling Dante to a purer understanding of divine justice. Her final act—returning to her throne in the Mystic Rose—demonstrates her role as a completed intermediary, having brought Dante to the threshold of direct divine vision.

Her character reveals the essential role of divine grace in spiritual elevation.

St. Bernard

St. Bernard of Clairvaux appears in the final cantos of Paradiso, serving as Dante’s final guide.

A mystic and a passionate devotee of the Virgin Mary, Bernard symbolizes contemplative devotion and mystical insight. Where Virgil embodied reason and Beatrice divine wisdom, Bernard channels spiritual love and intercessory prayer.

His function is to prepare Dante for the ultimate vision of God by turning his focus to the Virgin Mary, whose intercession is necessary for the beatific vision. Bernard’s prayer to Mary, poetic and exalted, reflects both his reverence and his mystical theology.

His presence bridges the human and divine, making him an ideal guide for Dante’s final ascent. Through Bernard, Dante experiences the culmination of his spiritual transformation, moving from intellectual inquiry to pure mystical union.

Bernard’s calm, meditative nature and theological depth make him the perfect final conduit through which Dante enters the presence of the divine.

Francesca da Rimini

Francesca da Rimini appears briefly in Inferno but leaves a lasting emotional imprint on both Dante and the reader. Condemned to the Second Circle of Hell for adultery, Francesca tells her story with a poignant mix of sorrow and romantic fatalism.

She fell in love with her husband’s brother, Paolo, after reading about Lancelot and Guinevere. Their shared reading becomes a symbol of the seductive power of literature and the dangers of unchecked desire.

Francesca speaks with grace and tragedy, and her account profoundly moves Dante, causing him to faint out of pity. However, her refusal to acknowledge her sin and her self-justifying tone subtly reinforce Dante’s moral framework: sympathy must not override justice.

Her character captures the complex interplay of passion, responsibility, and moral consequence, making her one of the most memorable figures in Hell.

Statius

Statius, a Roman poet and Christian convert, appears in Purgatorio as a companion to Dante and Virgil. Having completed his purgation, he symbolizes the harmony between classical virtue and Christian faith.

He credits Virgil’s poetry—especially the Eclogue IV—with awakening his spiritual awareness, though he admits he kept his faith secret out of fear, which condemned him to the Cornice of Sloth. Statius bridges the gap between Virgil’s pagan wisdom and Beatrice’s divine insight.

His presence affirms the transformative power of literature and foreshadows the transition from reason to revelation. His joy upon meeting Virgil is touching and sincere, but Virgil’s reminder that honor is meaningless among shades underscores the humility required for salvation.

Statius’ inclusion in the narrative demonstrates the permeability between secular greatness and divine truth.

Charon

Charon, the infernal ferryman of Greek mythology, is reimagined by Dante as the gatekeeper of Hell. His wrathful reluctance to ferry a living soul signals his awareness of divine authority yet his resistance to it.

His violent demeanor and the chaotic rush of the damned across Acheron dramatize the moment souls accept eternal punishment. Charon’s role is brief but vivid, reinforcing the idea that divine justice commands all, even infernal agents.

He represents the inevitability of judgment and the beginning of irreversible damnation. His presence at the threshold of Hell marks the transition from ignorance to awareness for Dante and the reader alike.

Themes

The Journey of Moral Awakening and the Recognition of Sin

From the opening lines of The Divine Comedy, the narrative is anchored in a deeply personal crisis—Dante’s lostness in a dark wood. This forest, filled with anxiety and terror, is more than a physical location; it embodies spiritual and moral disorientation.

Dante’s inability to ascend the hill of salvation due to the beasts represents his incapacity to confront sin directly without divine intervention. This marks the beginning of a painful process: confronting the nature of sin, acknowledging his own complicity, and recognizing the necessity of outside help—both reason and grace—for salvation.

As he journeys through the vestibule and into the initial circles of Hell, he encounters the Opportunists, the Carnal, the Gluttons, and the Wrathful. Each group is characterized by an unwillingness to take responsibility or act with virtue in life.

The punishments reflect their moral failures, not just externally but in the very way they relate to existence. Dante’s reactions—pity, sorrow, horror, and eventually anger—mirror his evolving understanding of sin.

These encounters are not abstract philosophical arguments; they are vivid, often grotesque dramatizations of the soul’s consequences for failing to live rightly. The progression from passive horror to active moral judgment suggests Dante’s growing spiritual maturity.

This journey of recognition is painful, but it is essential: one cannot begin to heal what one refuses to name. Through this theme, The Divine Comedy insists that genuine moral awakening begins with the clear-eyed acceptance of one’s own failings and the understanding that evil must be named and condemned before it can be overcome.

The Limits and Necessity of Human Reason

Virgil’s presence as Dante’s guide is emblematic of the high regard for reason, learning, and classical wisdom. In Limbo, Dante honors ancient poets and philosophers, recognizing the immense dignity of human intellect and virtue.

The Citadel in Limbo represents the height of what reason can achieve unaided—nobility, wisdom, and a pursuit of truth—but it is also defined by absence: these souls will never see God. The light of reason shines, but it cannot cross the threshold into divine truth without grace.

This limitation becomes stark when Virgil is unable to open the gates of Dis. The rebellion of the fallen angels—evil in its most hardened form—cannot be overpowered by intellect or argument.

The intervention of a divine messenger shows that human reason, while noble, is ultimately powerless against entrenched spiritual corruption without divine authority. Similarly, in Purgatorio, Virgil admits that he cannot explain why love can err without Beatrice’s revelation.

These moments do not diminish reason’s value but clarify its scope. Reason can guide, illuminate, and steady the will, but it cannot redeem.

Only when reason acknowledges its limits and is complemented by divine revelation and love can the soul progress. This theme is central to The Divine Comedy’s theological vision: faith and reason are not rivals but partners, and true understanding requires their harmony.

Dante’s journey affirms that while reason is necessary for moral and philosophical clarity, it must eventually yield to divine truth, which surpasses all earthly comprehension.

The Power and Responsibility of Free Will

Throughout The Divine Comedy, the soul’s freedom to choose is emphasized as both its highest gift and greatest burden. Virgil’s philosophical discourse on love in Purgatorio clarifies that every soul is naturally inclined to pursue what it believes is good.

This desire is not sinful in itself; the problem arises when it is misdirected. Love, like a river, must be channeled correctly.

When it flows toward the wrong objects or with the wrong intensity, it results in sloth, gluttony, avarice, or lust. Thus, moral failure is not due to love’s existence, but to the failure of the will to moderate and orient it.

Dante encounters souls who either acted without measure or failed to act at all, from the Opportunists who refused to take moral stands to the Slothful who lacked the zeal to pursue the good. In each case, their punishment is a distortion or exaggeration of the choice they made—or failed to make.

Even in Heaven, free will remains operative: souls rejoice not because they are forced, but because they align their will entirely with God’s. The punishments and rewards across Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise are never arbitrary; they are the logical outcomes of the soul’s exercise of will.

This makes salvation deeply personal. No one is passively damned or saved.

The soul is responsible for how it uses its freedom, and prayer, grace, and guidance exist to assist, not override, that agency. In this way, The Divine Comedy presents human freedom as a sacred responsibility that determines eternal destiny.

The Role of Divine Grace and Intercession

Dante’s journey would not begin, much less succeed, without the interventions of Beatrice, Saint Lucia, and the Virgin Mary. These figures act not through abstract decrees but through compassion, love, and a desire for Dante’s salvation.

Their intercession shows that divine grace often manifests through relationships, care, and mercy. Virgil, too, is enlisted through Beatrice’s appeal, showing that even human reason can become a channel of grace when inspired by divine love.

In Purgatorio, this grace becomes even more visible. Pope Adrian V’s plea for his niece’s prayers and Forese Donati’s gratitude for his wife’s intercessions underscore the communion of saints—the idea that the prayers of the living can impact the dead.

Souls are not isolated; they exist in a spiritual community where love transcends death. Grace does not erase responsibility, but it empowers the soul to recognize sin, desire righteousness, and move toward God.

Without Beatrice, Dante would remain trapped in the dark wood. Without the angel at Dis, he would be turned away.

Without prayer, souls in Purgatory would ascend more slowly. Grace operates not as a magical rescue but as an invitation and a force that makes transformation possible.

The theme emphasizes that salvation is not earned purely by merit but is the fruit of divine generosity. The Divine Comedy thereby affirms a theological vision in which God is both just and merciful, and grace is both a gift and a calling that the soul must respond to freely and faithfully.

The Consequences of Misused Desire and Material Excess

Across all three realms, Dante returns again and again to how desire—particularly for material wealth or bodily pleasure—can become a trap. The Gluttons in Hell lie in filth, tormented by what they once overindulged in.

The Avaricious and the Wasters are punished by being weighed down or forced into meaningless motion, echoing their obsession with either hoarding or squandering. In Purgatory, those guilty of similar sins suffer not through grotesque torment but through deprivation and longing.

The Gluttons there are emaciated, tormented by the aroma of food they cannot reach. But this suffering is redemptive—it trains their desire to be directed not toward perishable satisfaction, but toward divine fulfillment.

Statius explains how his love of poetry, and eventually his conversion to Christianity, stemmed from turning away from empty materialism. Hugh Capet laments how his dynasty’s greed corrupted the state and the church, showing how personal sins can metastasize into political and ecclesial disaster.

In Paradise, by contrast, all desire is rightly ordered—souls desire God above all, and this alignment brings joy and peace. Throughout The Divine Comedy, Dante warns that disordered desire leads to bondage, blindness, and degradation.

But he also suggests that desire, when purified and reoriented, becomes the engine of salvation. What matters is not that one desires, but what one desires most.

The soul must learn to hunger for the eternal, not the ephemeral. Thus, the journey from Hell to Paradise is, in one sense, the transformation of desire itself—from carnal craving to spiritual longing.