The End of Drum-Time Summary, Characters and Themes

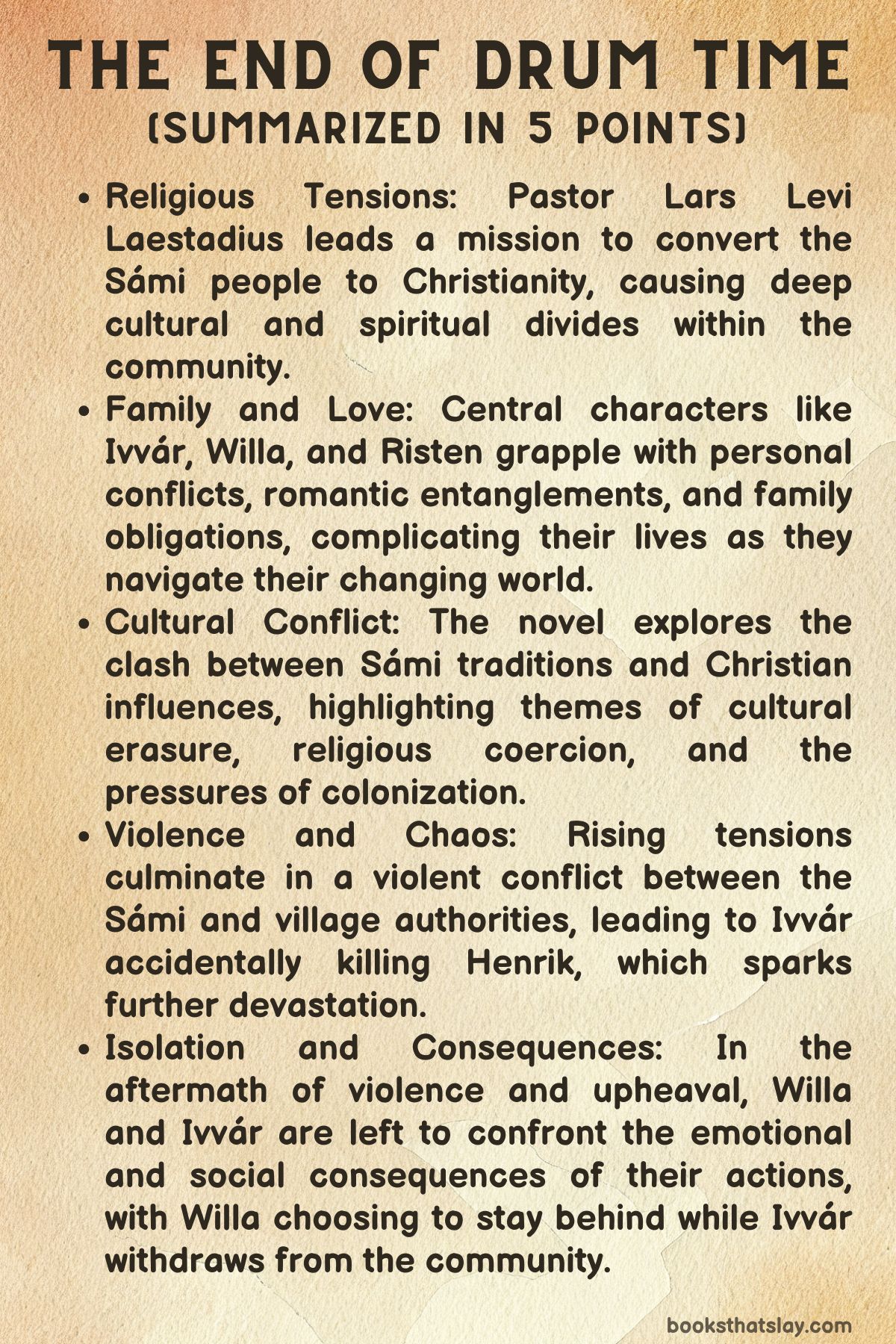

The End of Drum-Time by Hanna Pylväinen is a gripping historical novel set in 19th-century Sweden, focusing on the Sámi people and their struggle for identity amidst religious and cultural upheaval.

At its heart, the novel explores themes of faith, love, and survival as a small community is torn apart by Christian missionary efforts and societal changes. The characters’ personal journeys intertwine with the broader tensions of cultural erasure and religious coercion, making this novel a poignant examination of the consequences of colonization and the cost of forsaking one’s roots.

Summary

The novel begins in a remote northern village on the shortest day of the year. Pastor Lars Levi Laestadius, a spiritual leader and botanist, is troubled by an unclear vision. As the Sámi and Finnish villagers gather in the church, Henrik, the bell ringer, sneaks away to sell bootlegged alcohol.

Meanwhile, Biettar Rasti, a reindeer herder and one of the Sámi, collapses in the church, which Lars Levi interprets as a spiritual revelation.

A sudden earthquake interrupts the service, triggering a panic among the congregation, while Willa, the pastor’s daughter, believes this is a divine message meant for her.

Elsewhere, Ivvár, Biettar’s son, grapples with the difficult winter and his responsibilities managing the reindeer in his father’s absence. He grows increasingly frustrated, assuming his father has succumbed to drinking again.

Ivvár’s thoughts frequently return to Risten Tomma, a young Sámi woman with whom he has a romantic connection, despite her engagement to another man, Mikkol Piltto.

When Biettar returns home, he speaks passionately about his newfound Christian faith, much to Ivvár’s confusion and resentment. Biettar’s frequent visits to the pastor’s home, an unusual relationship between a Sámi man and a village pastor, stirs tensions in the community, as Willa finds herself drawn to Ivvár.

Old Sussu, an elder of the Sámi community, is troubled by Biettar’s conversion and shares her misgivings with Risten’s family, suspecting that Ivvár’s influence is disrupting Risten’s engagement.

Torn between her loyalty to her people and her love for Ivvár, Risten becomes increasingly conflicted. As the village faces the harsh realities of winter and reindeer attacks, the weight of tradition and survival deepens the community’s sense of unease.

During the Easter celebration, Willa’s desire for Ivvár intensifies, while he, overwhelmed, turns to alcohol.

When her brother Lorens falls seriously ill, Willa seeks Ivvár for comfort, but their connection is thwarted by their own insecurities and the watchful eyes of the community.

When Willa and Ivvár share a private moment in the sauna, they are discovered by Pastor Lars Levi, and Willa is punished and shamed by her family. Her isolation leads her to the Sámi camp, where she seeks solace.

Risten marries Mikkol, though her heart remains tied to Ivvár. Meanwhile, Henrik, the bell ringer, tries to redeem himself by proposing to Nora, Lars Levi’s daughter.

He renounces his alcohol business in a bid to prove his worth, but when Frans, the new pastor, takes control, tensions rise.

Frans encourages drinking while imposing harsh punishment on dissenters, even imprisoning Biettar after a public outburst.

As reindeer debt mounts and conflicts escalate, a violent confrontation occurs between the Sámi and the village authorities.

Henrik’s death at Ivvár’s hands leads to the destruction of his store and chaos among the reindeer.

In the aftermath, Willa decides to stay behind to support her family, while Ivvár, overwhelmed by guilt, disappears into the wilderness, leaving behind a fractured community grappling with the consequences of cultural and spiritual upheaval.

Characters

Lars Levi Laestadius

Lars Levi Laestadius, the pastor of the northern village, is central to the religious and cultural tensions that define the novel. He is deeply committed to his Christian faith and driven by a desire to convert the local Sámi people, who practice their traditional spirituality.

His authority in the community is both revered and resented, as he embodies a force of religious coercion that challenges the Sámi’s cultural identity. His spiritual unease, which manifests early in the novel through his troubling dream, hints at the deeper anxieties he harbors about the moral and spiritual state of the village.

His interactions with Biettar Rasti, the Sámi herder who converts to Christianity, reflect his belief that religious salvation must come at the cost of the Sámi’s traditional way of life. Despite his convictions, Lars Levi is not without personal conflicts, particularly concerning his daughter Willa, whose actions trouble him.

His failure to understand Willa’s needs, and his strict enforcement of religious rules within his own family, shows his inability to reconcile human emotions with the rigid moral framework he upholds.

Willa Laestadius

Willa is one of the most complex characters in the novel, caught between her father’s expectations and her personal desires. She is deeply religious, like her father, but her faith is tinged with a sense of personal calling that manifests in her interpretation of the earthquake as a divine message for her.

This growing spiritual fervor, combined with her budding feelings for Ivvár, places her at odds with the social and religious norms of her community. Her attraction to Ivvár, a Sámi man, signifies her emotional and spiritual rebellion against the cultural erasure her father represents.

As she grapples with her desires, Willa begins to see herself outside the rigid framework of her father’s world. The tension between her need for personal autonomy and the religious expectations imposed upon her ultimately leads to her social ostracism and emotional exile.

By the end of the novel, Willa’s transformation is profound. She becomes “Mad Willa,” a woman marked by the chaos and tragedy of the events around her, forced to confront the limits of faith, family, and societal expectations.

Ivvár Rasti

Ivvár is a young Sámi herder whose internal conflicts mirror the larger tensions between the Sámi way of life and the encroaching religious and cultural influence of the Swedish settlers. He struggles with his father Biettar’s absence, assuming it is due to alcoholism, which reflects his deep-rooted resentment and misunderstanding of his father’s spiritual conversion.

As Ivvár navigates the harsh winter, the responsibilities of herding, and his complicated romantic feelings for Risten Tomma, he finds himself increasingly confused and isolated. His relationship with Willa adds another layer of emotional complexity, as he feels drawn to her despite their cultural and social differences.

His frustrations eventually explode into violence when he kills Henrik during a struggle, a pivotal moment that shifts Ivvár from a conflicted young man into an individual whose actions have irrevocable consequences. This act of violence, along with his inability to fully reconcile his Sámi identity with the external pressures of religion and debt, leads him on a path of emotional and spiritual disintegration by the end of the novel.

Biettar Rasti

Biettar is a Sámi herder whose conversion to Christianity becomes a source of turmoil both within his family and the larger Sámi community. His transformation from a troubled herder to a devout Christian is seen as a betrayal by his people, particularly by Old Sussu, who represents the traditional Sámi worldview.

Biettar’s newfound faith brings him into close contact with Pastor Laestadius, and their theological discussions underscore the clash between Sámi spiritual beliefs and the Christian faith that Laestadius imposes. Despite his fervor, Biettar’s conversion isolates him from his son Ivvár, whose confusion and resentment only grow stronger as Biettar spends more time at the parsonage.

His arrest by Frans, the new pastor, for interrupting a church service highlights the growing power dynamics within the village, as the Sámi are increasingly marginalized. Biettar’s rescue by Ivvár during the violent confrontation at Henrik’s store reveals the strained, but ultimately unbreakable, bond between father and son.

However, Biettar’s fate remains tied to the cultural and religious turmoil that consumes the community.

Risten Tomma

Risten is a Sámi woman torn between her engagement to Mikkol Piltto and her unresolved feelings for Ivvár. Her internal struggle reflects the broader cultural tensions within the Sámi community as it faces pressures from both the natural environment and the encroaching influence of Swedish settlers.

Risten’s engagement to Mikkol represents her duty to family and community, but her attraction to Ivvár symbolizes a desire for personal freedom and emotional fulfillment. This conflict plays out against the backdrop of the community’s economic hardships, such as debt and wolverine attacks on the reindeer herd, which compound the personal challenges she faces.

Her marriage to Mikkol does not resolve her feelings for Ivvár, and she continues to reflect on the complexities of love, duty, and community throughout the novel. Risten’s journey with the Sámi to Gilbbesjávri after Willa’s ostracism represents her attempt to move forward, but the emotional scars of her relationship with Ivvár linger, leaving her in a state of unresolved tension.

Henrik

Henrik, the bell ringer who sells illegal alcohol, represents a more pragmatic and morally ambiguous figure in the novel. His decision to sell alcohol, despite the prohibitions of Pastor Laestadius, positions him in opposition to the strict religious values of the community.

However, his character is not purely antagonistic. His relationship with Nora, one of Laestadius’s daughters, shows that he is capable of love and redemption. When he destroys his liquor stock to gain the approval of Nora’s family and marry her, he demonstrates a willingness to change, even if it comes at great personal cost.

However, Henrik’s actions later in the novel, particularly his involvement in the conflict over reindeer debt collection, show that his attempts at redemption are ultimately undermined by the harsh realities of survival in the region. His death at the hands of Ivvár is both a tragic and symbolic moment, highlighting the violent clash between the competing economic, cultural, and spiritual forces in the village.

Frans

Frans, the new pastor who replaces Lars Levi Laestadius, serves as a foil to the more spiritually driven Laestadius. Whereas Laestadius is focused on conversion and moral discipline, Frans brings a much harsher and more hypocritical form of religious enforcement to the community.

His encouragement of alcohol consumption, combined with his violent treatment of parishioners, makes him an authoritarian figure whose presence exacerbates the existing tensions. Frans’s decision to imprison Biettar for interrupting a church service illustrates his lack of compassion and his prioritization of control over spiritual guidance.

His role in the conflict with the Sámi, particularly his involvement in the attempt to seize reindeer as debt repayment, positions him as a direct antagonist to the Sámi community. His rigid, authoritarian approach ultimately contributes to the breakdown of order in the village, as his actions fuel the violence and chaos that culminates in Henrik’s death and the burning of the store.

Themes

The Conflict of Cultural Erasure and the Struggle for Identity Amid Colonization and Religious Coercion

One of the most profound themes in The End of Drum-Time is the painful intersection of cultural erasure and religious coercion. Set against the backdrop of 19th-century Sweden, where the indigenous Sámi people are grappling with the encroaching influence of European settlers and the Christian church, the novel explores how colonization operates not just through overt domination but through more insidious means of religious conversion and economic dependence.

The character of Pastor Lars Levi Laestadius embodies the forces of religious and cultural domination, presenting Christianity as a way of salvation but also as a tool for erasing the Sámi’s traditional beliefs and practices. Biettar Rasti’s conversion serves as a particularly charged symbol of this erasure, as his adoption of Christian faith distances him from his son Ivvár and the larger Sámi community, causing confusion and disorientation.

This theme delves into the psychological and cultural conflicts that arise when indigenous identities are subjugated by foreign religious dogma. It exposes how colonization often disguises itself as spiritual salvation while erasing local traditions and social structures.

The novel doesn’t present this process in a simplistic binary of oppressor versus oppressed. Instead, it highlights the complexities of belief, conversion, and cultural survival in the face of coercion.

The Intersection of Religious Fervor, Personal Guilt, and Social Ostracism in a Calvinistic Framework

Closely related to the novel’s examination of cultural erasure is its exploration of personal guilt and social ostracism within the religiously charged environment of 19th-century Sweden. Willa, the pastor’s daughter, becomes a focal point for this theme as she grapples with her spirituality, her longing for Ivvár, and the overwhelming sense of guilt that accompanies her transgressions.

Her affair with Ivvár, particularly her punishment and subsequent social isolation, reflects the way Calvinistic doctrines of sin and guilt pervade not just personal lives but the entire community’s social fabric. Willa’s inner turmoil and eventual ostracism show how deeply religious fervor can be intertwined with mechanisms of social control, where individuals are judged not just for their actions but for their perceived alignment with strict moral codes.

The fear of moral failure drives many characters’ decisions, further illustrating the inescapable grip that religious ideology holds over their lives. The novel critiques the rigidity and punitive nature of these belief systems, emphasizing how spiritual zeal can turn into a means of suppression.

The Complexity of Interpersonal Relationships in the Context of Power, Debt, and Social Hierarchy

The novel also weaves a complex theme surrounding interpersonal relationships within the broader context of economic dependency and social hierarchy. Ivvár’s struggle to manage the reindeer herd under the weight of debt is emblematic of the precarious economic status of the Sámi people, who find themselves increasingly tied to external systems of power and control.

His complicated relationships with both Risten and Willa are not simply matters of love and desire but are fraught with the complications of economic pressure and social standing. Mikkol Piltto’s engagement to Risten and the tension with Ivvár reflect how personal matters like marriage are deeply intertwined with economic survival and social cohesion within a community.

Henrik’s role as a bell ringer and illegal liquor seller positions him as both a rebel and an exploiter. His death during the struggle over reindeer and debt underscores how power dynamics inevitably lead to violence as social pressures collapse under unsustainable systems of exploitation.

Thus, the novel portrays relationships not as isolated emotional bonds but as deeply embedded within broader structures of power and survival.

The Psychological Impact of Displacement and the Tensions Between Nomadic Tradition and Settler Colonialism

Another deeply layered theme in The End of Drum-Time is the psychological and emotional toll of displacement. The Sámi people face the encroaching forces of settler colonialism, and their nomadic lifestyle, based on the seasonal movement of reindeer herds, is increasingly threatened by new political borders and economic pressures.

The novel explores how displacement forces the Sámi to navigate new and hostile environments, both literally and metaphorically. For Ivvár and Willa, their respective searches for belonging are complicated by the dissolution of their traditional ways of life.

Willa’s desire to integrate into the Sámi community contrasts with Ivvár’s increasing alienation from his culture.

This mirrors the broader theme of how colonized peoples often find themselves caught between two worlds—neither able to return to their roots nor fully able to assimilate into new structures.

This psychological dislocation is central to the novel’s portrayal of the Sámi experience, capturing the profound sense of loss and identity crisis that accompanies colonization.

Violence as an Inevitable Product of Systemic Oppression and the Cycle of Resistance

The novel examines the inevitable rise of violence as a response to systemic oppression, framing it as both a personal and collective act of resistance. Ivvár’s decision to kill Henrik is not presented as an impulsive moment of brutality but as the culmination of pressures that have built up over time.

His actions reflect a desperate attempt to reclaim agency in a world where both the Sámi people and his family have been systematically disempowered.

The broader context of this act—the struggle over reindeer, debt, and the imprisonment of his father—shows how violence becomes a form of resistance when all other avenues are closed.

The fire that engulfs Henrik’s store serves as a metaphor for the uncontrollable nature of resistance, suggesting that violence, once unleashed, can spiral out of control. The novel portrays violence not as a simple act of rebellion but as the tragic consequence of sustained oppression and exploitation.