The Engagement Party by Finley Turner Summary, Characters and Themes

The Engagement Party by Finley Turner is a modern psychological suspense novel set against the backdrop of extreme wealth, buried trauma, and manipulative family dynamics.

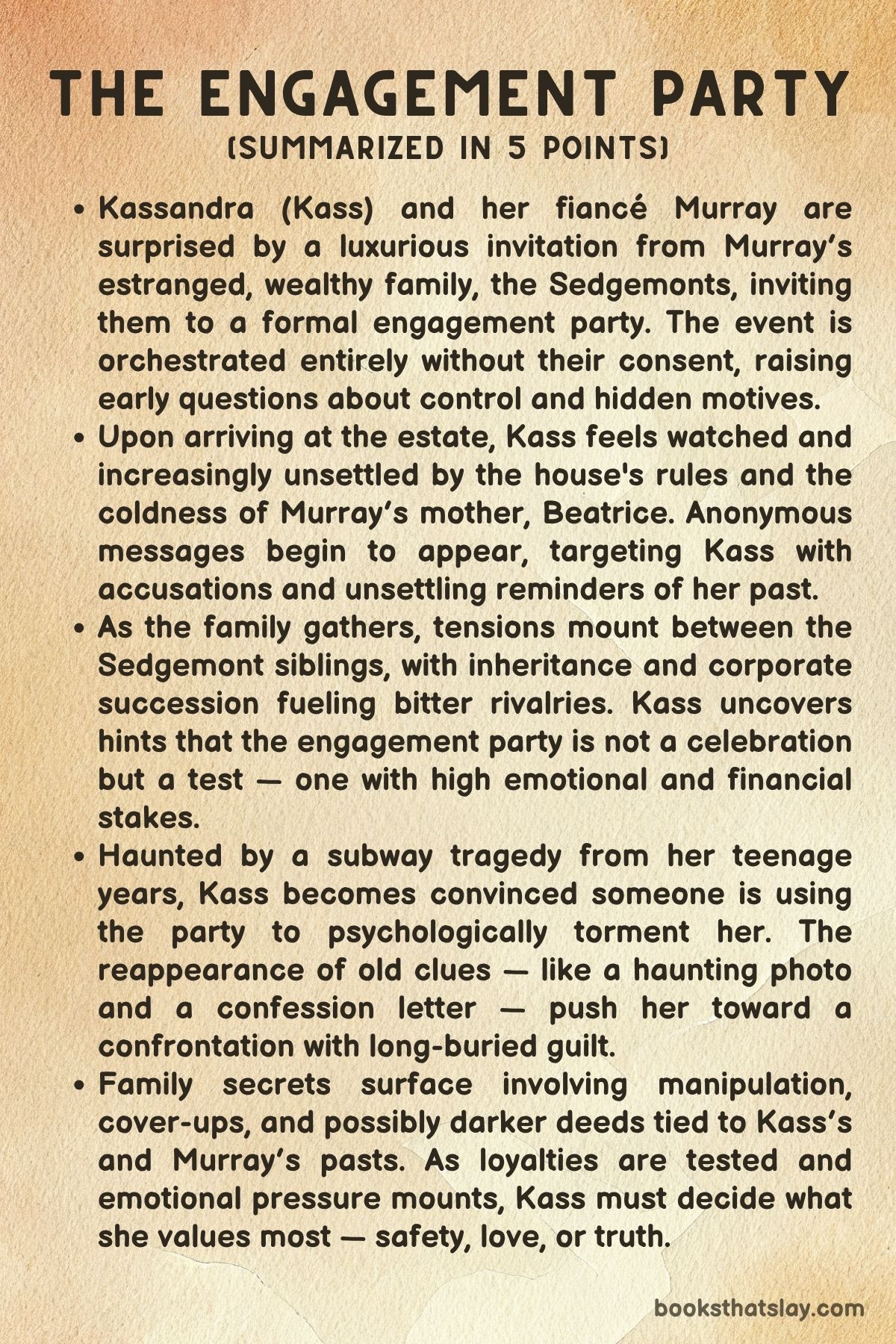

When Kass, a rising set designer in New York, accepts a surprise invitation to an opulent engagement party hosted by her fiancé Murray’s estranged, ultra-wealthy family, she finds herself caught in a game of secrets and social warfare.

What starts as a celebration quickly turns sinister as anonymous messages, eerie surveillance, and long-buried memories rise to the surface.

The novel blends emotional introspection with mystery, as Kass navigates not only her relationship but the ghosts of her past.

Summary

The novel opens with Kass haunted by a traumatic memory tied to a subway platform. Though she tries to live in the present, guilt anchors her to a singular moment from her past.

When she gets engaged to Murray, their love feels genuine, but things begin to unravel quickly. A mysterious, formal invitation arrives from Murray’s estranged family — the Sedgemonts — inviting them to a lavish engagement party neither of them arranged.

The Sedgemont estate is enormous and intimidating. Murray, who had kept his wealth a secret, is forced to confront a past he’d avoided.

Kass meets his family: his cold, powerful mother Beatrice, his unsettling twin brothers Emmett and Kennedy, and a number of enigmatic guests and servants. From the moment she arrives, Kass feels watched, judged, and subtly undermined.

Her room is monitored, her dress disappears, and anonymous threatening messages appear on her phone and mirrors. Phrases like “You don’t deserve happiness” and “Murderer” seem to pierce directly into her psyche.

As Kass tries to acclimate to her surroundings, tensions build. Beatrice appears less interested in welcoming her future daughter-in-law and more invested in testing her.

The estate staff, especially the housekeeper Gloria, behave with quiet dread. Through overheard conversations and strange encounters, Kass realizes she may be part of a calculated game — one that could have legal, emotional, and financial consequences for the Sedgemont dynasty.

At the same time, fragments of Kass’s past begin to surface. She recalls a friendship with a girl named Lena and a night at a subway station that ended in tragedy.

Someone at the estate seems to know about that night. Kass finds a photograph from the incident, receives a letter describing it in painful detail, and uncovers files in Beatrice’s office suggesting the family may have had the incident buried to protect Murray’s image.

Meanwhile, Murray reveals his own hidden truths. He was once engaged to a woman who disappeared, and his mother used her influence to erase the scandal.

This confession creates a rift between him and Kass, who now doubts how much of their life together is built on secrets. Kass confronts Beatrice, who confirms that the engagement party was never meant to celebrate but to evaluate — a test to see whether Kass could be folded into the family or pushed out.

Beatrice even offers Murray a choice: give up Kass and inherit the family business, or stay with her and be cut off entirely. As Kass prepares to leave the estate, a fire erupts during the party.

Amidst the chaos, Kass and Murray escape into the woods and flee the toxic environment. The next morning, he drives her to the airport.

They part ways — not in anger, but with understanding. They love each other, but the wounds left by family control, guilt, and silence are too deep to ignore.

Weeks later, Kass finds herself at a subway platform again — but this time, calm and steady. She’s on her way to a new job, wearing her necklace but no engagement ring.

Characters

Kassandra “Kass”

Kass is the emotional and psychological core of the novel. A talented but overworked set designer, she is marked by an unresolved trauma from her past involving the death of her friend Lena at a subway platform.

This moment continues to haunt her psyche. Her inner world is fragmented, stitched together by denial, guilt, and a desperate need for self-forgiveness.

Her love for Murray initially seems like a reprieve, a symbol of hope and new beginnings. But the journey to the Sedgemont estate plunges her deeper into a psychological labyrinth.

Kass transforms from a tentative guest trying to fit into her fiancé’s world into a resilient woman determined to confront not only the cruel manipulations of the Sedgemont family but also her buried past. Her arc is not about achieving romantic closure but rather about reclaiming agency, accepting her past, and seeking emotional rebirth.

By the end of the story, she is no longer a woman running from a traumatic memory. She is someone who chooses truth, even at the cost of love and comfort.

Murray Sedgemont

Murray is an intriguing paradox — warm, witty, and genuinely affectionate toward Kass, yet defined by evasion and secrecy. He distances himself from his wealthy lineage, presenting himself as a man who wants love without strings.

His decision to hide his family’s fortune and past reflects both shame and a deep fear of being loved for the wrong reasons. As the story unfolds, it becomes clear that Murray is both a victim and an unwitting enabler of his family’s toxicity.

The revelation of his previous engagement, and the possibility that his family covered up a disappearance, add a sinister undertone to his otherwise kind demeanor. However, Murray undergoes a transformation as well.

When Kass is cornered and endangered by his family’s cruel machinations, he finally severs ties with Beatrice and the Sedgemont legacy. He chooses integrity and Kass’s well-being over power.

He ultimately becomes a man willing to sacrifice privilege for principle. Though this clarity comes too late to preserve his relationship with Kass.

Beatrice Sedgemont

Beatrice is the matriarchal tyrant of the Sedgemont family. She embodies cold ambition and aristocratic elitism.

Every move she makes is strategic, cloaked in civility but dripping with venom. Her affection is transactional, her hospitality a facade, and her sense of “family” is rooted in control and image rather than love.

Beatrice’s manipulation of Kass — from altering her dress to isolating her psychologically — is orchestrated with surgical precision. Her ultimate goal is to maintain the Sedgemont dynasty, and if that means humiliating or destroying Kass, so be it.

Her villainy is not merely personal. She represents the broader, corrosive influence of unchecked wealth and legacy.

She weaponizes secrets and suppresses inconvenient truths, including Kass’s past and even a potential crime linked to Murray’s ex. Beatrice is terrifying not because she is emotional, but because she is ruthlessly calculating.

Her belief in her own moral superiority renders her a deeply chilling figure.

Kennedy and Emmett Sedgemont

Kennedy and Emmett, Murray’s twin brothers, serve as cryptic foils to his relative normalcy. They are polished, predatory, and passive-aggressively cruel.

Kennedy, especially, thrives on psychological games. His interactions with Kass are laced with insinuation, doubt, and veiled threats.

He is a master manipulator, prodding at her insecurities and suggesting that her place in the family is a fabrication or a test. Emmett is slightly more restrained but no less complicit in the family’s toxic culture.

The brothers act as gatekeepers to the Sedgemont power structure. Their behavior hints at a long history of sabotaging those who threaten it.

Their role in the family’s larger schemes — particularly around inheritance, corporate succession, and past romantic entanglements — makes them emblematic of how affluence and privilege can rot familial bonds into bitter competition.

Gloria

Gloria, the housekeeper, is perhaps the novel’s most quietly tragic character. She appears initially as just another background servant, loyal and dutiful.

As the story unfolds, her deeper knowledge and veiled warnings reveal a lifetime spent under the Sedgemonts’ thumb. Her quarters in the basement contrast starkly with the mansion’s grandeur, symbolizing her relegated status despite Beatrice’s patronizing assertion that she’s “family.”

Gloria sees everything but says little. Her caution comes from experience.

She drops hints, offers cryptic advice, and ultimately confirms what Kass begins to suspect. The Sedgemonts have destroyed more lives than just hers.

Gloria is a survivor of the Sedgemont machine. In Kass, she sees someone who still has a chance to escape.

Lena

Though dead before the novel begins, Lena haunts its every chapter. She is more than a memory — she is a specter of guilt, a symbol of lost innocence, and an embodiment of unresolved trauma.

Kass’s flashbacks depict Lena as vibrant, troubled, and caught in a complicated dynamic with her friend. The incident at the subway — left murky until later chapters — becomes a psychological pressure point for Kass.

It is Lena’s unspoken forgiveness, delivered through anonymous letters and mirrored memories, that catalyzes Kass’s ultimate growth. Lena’s “presence” represents the novel’s strongest emotional undercurrent.

This includes the price of silence, the cruelty of self-blame, and the slow, painful path to forgiveness.

Themes

Trauma and Guilt

One of the novel’s most important themes is the enduring weight of personal trauma and the corrosive nature of unresolved guilt. Kass, the protagonist, is haunted by a singular moment from her past — a subway incident that ended in the death of a friend, Lena.

This tragedy is not presented as a distant memory but as an ever-present psychological scar that influences every aspect of Kass’s emotional life. Her guilt is not only self-imposed but is externalized through anonymous messages that echo her internal fears, suggesting that someone else knows her secret and blames her for it.

This constant external pressure amplifies her already fragile mental state, trapping her in a cycle of self-blame and fear. The guilt isn’t simply a plot device; it defines her identity, influences her relationships, and serves as a barometer for her sense of self-worth.

Even as she tries to move forward with her engagement and career, Kass cannot escape the shadow of her past. The story draws a clear line between trauma that remains buried and trauma that is confronted.

Her journey toward healing is not clean or redemptive in a traditional sense, but it is honest. By the novel’s end, she does not erase the guilt but learns to live beside it, acknowledging it as part of her past rather than allowing it to dictate her future.

The theme emphasizes that true recovery often lies not in forgetting but in acceptance and growth.

Power and Control

Control—particularly who holds it and how it is wielded—is a persistent and oppressive theme throughout the novel. The Sedgemonts, with their staggering wealth and social influence, exemplify a class of individuals for whom manipulation is a form of tradition.

Beatrice Sedgemont, the matriarch, uses her authority not just to orchestrate events like the engagement party but to manipulate the emotional landscape of those within her orbit. The party itself is less a celebration and more a test—an elaborate performance designed to assert dominance and control outcomes.

Even in seemingly benign gestures, such as replacing Kass’s dress or assigning separate rooms, Beatrice subtly asserts her superiority and reshapes Kass’s autonomy. The dynamic is not limited to class power; emotional control also surfaces in the personal relationship between Kass and Murray.

His initial withholding of his family’s status, his fear of Kass’s judgment, and his eventual confession are all marked by moments of emotional power shifts. Control is also psychological—reflected in how anonymous messages torment Kass, manipulating her actions and emotions through fear and uncertainty.

The house itself, with its locked doors, hidden rooms, and omnipresent surveillance, becomes a metaphor for the Sedgemont power structure: beautiful, refined, and quietly suffocating. By the end, as the house burns and Kass leaves, the narrative asserts that relinquishing control—especially toxic, manipulative control—is essential to reclaiming agency.

The novel suggests that resisting power structures requires immense emotional strength and that breaking free from coercive environments is a form of liberation.

Class and Social Boundaries

Class distinctions shape nearly every interaction in The Engagement Party, exposing the fault lines between those who possess power and those who merely navigate its terrain. Kass enters the Sedgemont world as an outsider, not only because of her financial background but because of her values, mannerisms, and assumptions about intimacy and trust.

Her discomfort is immediate, rooted in the vast physical and emotional differences between her modest upbringing and the excessive, curated elegance of the Sedgemont estate. The wealth on display is not just decorative; it functions as a gatekeeping mechanism, a way of delineating who belongs and who does not.

The fact that Beatrice stages the engagement party without Kass’s or Murray’s input is a demonstration of this very boundary—Kass is welcome only on their terms, never as an equal. Even within the Sedgemont family, class-based hierarchy plays out.

Characters like Gloria, the housekeeper, live under the illusion of being “part of the family,” when in truth, they occupy a servile role that is masked by superficial affection. The deeper implication is that wealth buys not just privilege, but moral exemption.

The family’s ability to suppress past scandals and manipulate public perception shows how class becomes a shield against consequences. Kass’s increasing alienation from this world illustrates the cost of trying to cross these social boundaries.

Ultimately, the novel posits that wealth can corrupt relationships, distort loyalty, and blur ethical lines, making love, truth, and identity subject to the whims of those in power.

Identity and Self-Reclamation

At its core, The Engagement Party is a story about identity—not the one assigned by birth or circumstance, but the one forged through trial, fear, and choice. Kass begins the novel somewhat untethered, caught between who she was before the subway incident and who she might become as Murray’s fiancée.

The engagement initially appears to offer her a stable future, a kind of redemption arc away from her haunted past. However, as the layers of both her own trauma and the Sedgemont family’s secrets begin to unfold, Kass is forced to reevaluate not just her relationships but her very sense of self.

The constant surveillance, gaslighting, and manipulation she experiences begin to strip away her certainty, leading to moments of near disintegration. Yet, instead of crumbling, Kass begins to fight back—asserting her voice, uncovering the truth, and making painful but necessary decisions.

Her final act of walking away from both Murray and the Sedgemonts, despite her love for him, is not a defeat but an act of profound self-reclamation. She chooses autonomy over security, truth over illusion.

The closing scene—Kass alone on a subway platform, no longer paralyzed by fear—is a powerful image of rebirth. She is not defined by her engagement, her guilt, or her proximity to power.

She is someone who survived, who refused to be shaped by trauma or expectation, and who now steps forward by her own volition. The novel treats identity not as fixed, but as a dynamic, evolving construct shaped by the courage to confront one’s truth.