The Famine Orphans Summary, Characters and Themes

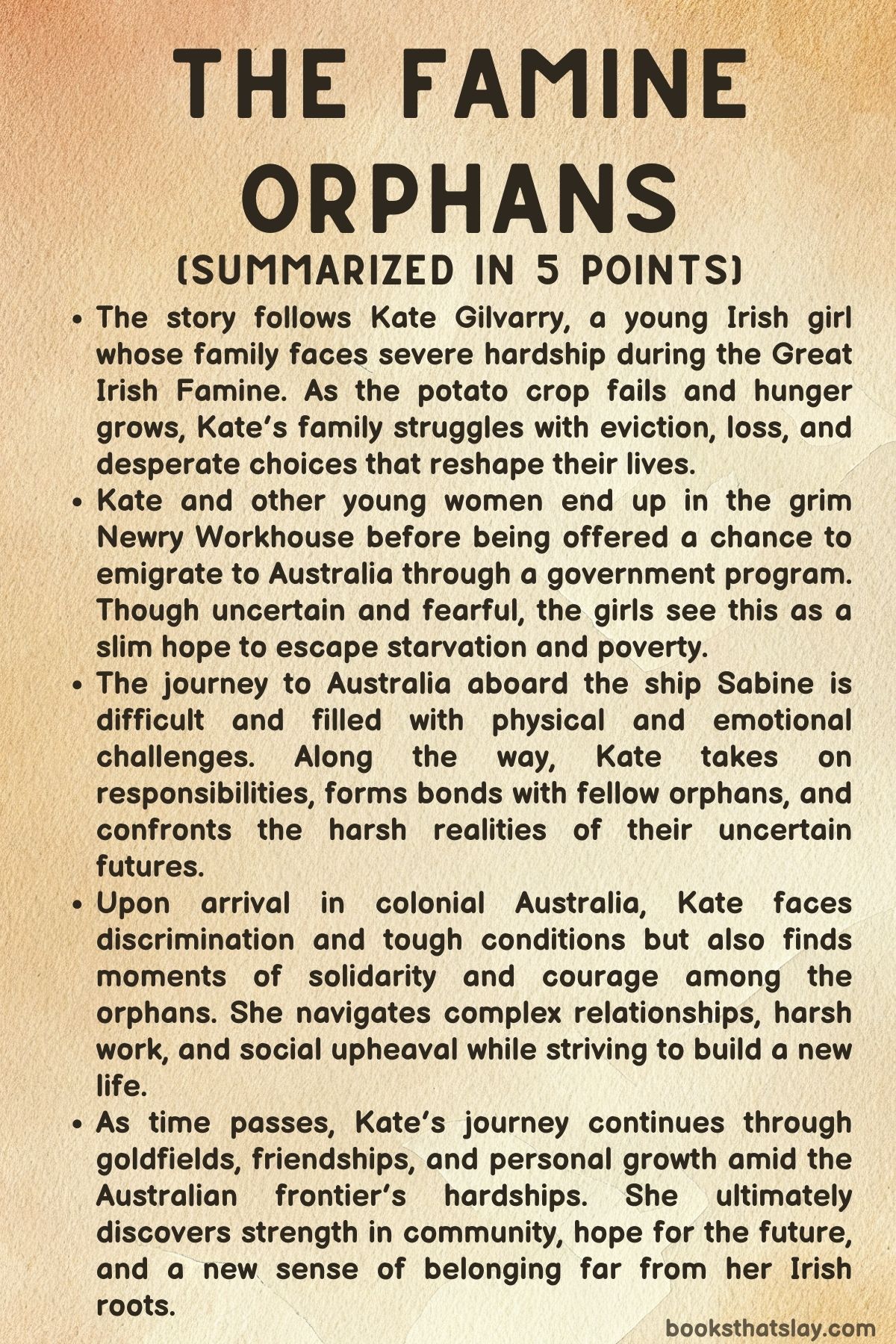

The Famine Orphans by Patricia Falvey is a vivid historical novel that traces the journey of Kate Gilvarry, a young Irish girl caught in the horrors of the Great Irish Famine and its aftermath. Told in the first person, Kate’s story begins in rural Ireland, where famine and eviction shatter her family’s life.

Forced into a grim workhouse and then selected for a government program, she is sent to Australia with other orphan girls. The narrative follows Kate through hardship, survival, and transformation—from her perilous sea voyage to the challenges of life in colonial Australia during the gold rush era. It’s a tale of resilience, friendship, and finding hope in a harsh new world.

Summary

Kate Gilvarry’s story starts in Upper Killeavy, South Armagh, Ireland, during the onset of the Great Irish Famine in 1845. The Gilvarry family depends heavily on their potato crop, which falls victim to a devastating blight.

The blight returns worse than before, ruining the potatoes and threatening the survival of the whole community. Kate’s family, tenant farmers renting from landlord Charles Smythe, face increasing hardship as food becomes scarce.

Kate’s father works hard, while her mother Mary, disowned by her Protestant family for marrying a Catholic, cares for the children—Paddy, Christy, Kate, and little Maeve. As the famine deepens, the family sells livestock to pay debts, but hunger worsens.

Young Maeve dies from starvation, and Paddy leaves for England to find work and support them.

Eventually, the landlord demands overdue rent, and with no means to pay, the family is evicted. They move to the Newry Workhouse, an overcrowded, grim place where the starving seek refuge.

Conditions there are harsh, food scarce, and diseases like dysentery rampant. Kate tries to maintain hope by teaching girls to read and write.

Her mother dies in the workhouse, and Christy becomes withdrawn and almost unrecognizable. The workhouse experience is crushing, but after some time, Kate and other young women learn about a British government scheme offering emigration to Australia.

This scheme promises paid passage and jobs as domestic servants and is seen as a way to escape starvation and poverty.

Despite fears and skepticism, the girls prepare for the journey, receiving supplies and clothing. Some, like Patsy Toner, a tough but vulnerable girl, initially do not qualify but eventually join.

Their journey begins with a difficult trip from Newry to Dublin, then by steamer to Plymouth, England, where they board the ship Sabine for Australia. Kate describes the harsh, cramped conditions aboard the ship: tight sleeping quarters, strict matrons, seasickness, and the spread of illness.

Life on board is physically and emotionally difficult, but moments of camaraderie and conflict occur among the orphans. Kate takes on duties to support her group and tries to keep order.

Under the care of Doctor Harte, a kind figure amidst strict discipline, Kate and the other girls endure daily chores and lessons in English, writing, and domestic skills. While many girls are skilled in sewing, some struggle, like Patsy, who eventually finds her strength in baking.

Despite the tough environment, the girls find comfort in singing, dancing, and shared experiences. They pass the island of Madeira and learn about geography, but homesickness grows.

The ship crosses the Equator, and tensions rise during the traditional initiation rites for sailors, which end tragically with a young sailor’s death. The group mourns deeply, and the ship’s atmosphere grows somber.

As the ship moves closer to Australia, the girls hear disturbing news about hostility toward Irish orphans in the colony. Despite fear and uncertainty, they support one another, especially Lizzie, who is secretly pregnant and vulnerable.

Kate maintains a complicated relationship with Doctor Harte, who shows care but keeps professional distance. The orphans prepare for arrival, facing scrutiny from matrons who will decide their futures.

Though scared, they hold on to hope.

Upon arrival in Australia, Kate finds herself working at Pitt House, serving wealthy guests while overhearing disparaging remarks about the Irish orphans from powerful men. She publicly confronts a newspaper editor, defending herself and her fellow orphans.

This defiance leads to her demotion to a scullery maid under harsh conditions, but Kate gains secret admiration for standing up. She finds support in friends like Bridie and Luke, a gardener with a convict past.

Kate begins to understand Luke deeply and starts to see a future beyond her hardships.

Kate and Bridie visit Patsy, who now lives in a brothel after failing to secure employment, highlighting the fragile lives many orphans face. Bridie develops a cautious romance with a hotel owner but hesitates to marry due to social constraints.

Meanwhile, Pitt House’s fortunes decline; staff are dismissed, and the house eventually sells. Luke proposes marriage to Kate—not out of passion, but for companionship and survival.

After some hesitation, Kate accepts, recognizing the stability it offers. They marry quietly with support from friends, and soon journey to Luke’s land in the Outback.

Life at Luke’s land, Tara, is challenging. The land is barren, and building a home is difficult.

With help from two former convicts, Malachy and Phineas, Kate begins adapting to this new life. Her hopes of returning to Ireland fade, but she finds strength in the land, Luke’s honesty, and her own resilience.

Later, Kate leaves Luke and reconnects with old friends Sheila and Lizzie in Bathurst, where they run a busy emporium supplying gold prospectors. She also reunites with Patsy, who dreams of opening a hotel to help women escape poverty.

Inspired by the gold rush, Kate applies for a mining license and sets out with Patsy, Malachy, and Phineas to seek fortune. They endure harsh conditions but support each other through the grueling work of mining.

When Phineas falls ill, Kate’s nursing skills and Patsy’s determination help save him. Their efforts lead to discovering a rich vein of gold, which they protect carefully.

Their discovery brings wealth, and back in Bathurst, they celebrate and plan futures: Sheila and Lizzie want to expand their business; Patsy aims to open her hotel; Malachy and Phineas look forward to settling down. Kate returns to Sydney to face her past, reunites with her brother Paddy, and confronts Nathaniel Harte, the doctor she once loved.

Nathaniel is engaged to another woman, but their feelings linger. Kate moves on, eventually divorcing Luke.

Kate opens a free school for immigrant and Aboriginal children, supported by Maria, an Aboriginal woman she befriends. Over time, the community grows stronger, and the bonds among the women from the ship remain firm.

At a farewell concert in Sydney’s Royal Theater, Kate, Nathaniel, and their friends celebrate survival and success. Bridie announces plans to return to Ireland, while Kate and Nathaniel rekindle their love, embracing hope and a future together built on resilience, friendship, and chosen family.

Characters

Kate Gilvarry

Kate Gilvarry is the central figure whose life story anchors the narrative of The Famine Orphans. Born in rural Upper Killeavy, South Armagh, she grows up in a close-knit tenant farming family deeply affected by the Great Irish Famine.

From a young age, Kate exhibits resilience, determination, and a keen sense of responsibility. The trauma of losing her siblings and mother, enduring eviction, and surviving the harsh conditions of the Newry Workhouse profoundly shapes her character.

Throughout her forced emigration and the grueling voyage to Australia, Kate emerges as a natural leader among the orphan girls, balancing a strong will with compassion. She takes on roles like teaching others and managing daily tasks, which shows her nurturing instincts and adaptability.

Upon arrival in Australia, Kate’s journey becomes one of self-discovery and empowerment as she navigates social prejudice, labor hardships, and complex relationships. Her confrontations with societal injustices, especially at Mrs.

Pitt’s garden party, reveal her fierce sense of justice and refusal to be silenced. Kate’s evolving relationships, particularly with Luke, her pragmatic yet kind husband, and Nathaniel Harte, a figure of past love and emotional complexity, highlight her internal struggle between survival and emotional fulfillment.

Ultimately, Kate embodies resilience—not just surviving immense loss and hardship, but carving out dignity, agency, and hope in a harsh new world.

Christy Gilvarry

Christy, Kate’s younger brother, represents the deep emotional toll famine and displacement have on children. His initial innocence is shattered by starvation and trauma, leading him to become withdrawn and almost unrecognizable to Kate over time.

His emotional distance symbolizes the psychological scars left by such catastrophic events. Christy’s gradual estrangement from his family mirrors the broader fragmentation caused by famine and emigration, highlighting how suffering affects not just physical survival but mental and emotional well-being.

Mary Gilvarry

Kate’s mother, Mary, is portrayed with warmth and quiet strength. Her background as a Protestant woman disowned by her family for marrying a Catholic farmer adds layers of social complexity and personal sacrifice.

Throughout the famine’s worsening conditions, Mary is a pillar of support and love within the family, though ultimately, she succumbs to the ravages of starvation in the workhouse. Her death marks a pivotal loss that propels Kate into a premature adulthood.

Mary’s story underscores the sacrifices made by women who bore the brunt of familial care during the famine, often at great personal cost.

Paddy Gilvarry

Paddy, Kate’s older brother, represents the desperate search for survival beyond the family farm. Leaving for England in hopes of finding work, he embodies the diaspora’s painful choices to abandon home for uncertain opportunities.

His absence weighs heavily on Kate, as he becomes a distant figure trying to support from afar. Paddy’s trajectory highlights the fractured nature of Irish families during the famine and the sacrifices demanded by survival.

Patsy Toner

Patsy Toner is a complex and vital figure among the orphan girls, symbolizing vulnerability masked by toughness. Initially excluded from the emigration scheme, Patsy’s journey from Newry to Australia is marked by resistance to authority and an uncertain future.

Her struggles, including her fall into prostitution and later attempts at reform, highlight the precarious position many young women faced amid poverty and social exclusion. Patsy’s narrative illustrates both the fragility and resilience of those cast aside by society, while her eventual determination to build a women-only hotel underscores her enduring hope for empowerment and community support for vulnerable women.

Bridie

Bridie emerges as a figure of unexpected sophistication and emotional depth among the orphans. A farm girl with knowledge of wealthy households, she quickly learns and adapts to new skills, becoming a symbol of hope and perseverance.

Her haunting Irish songs and emotional expressions provide a poignant connection to their shared homeland and lost past. Bridie’s close friendship with Kate and her romantic involvement with Mr.

O’Leary further add dimensions of personal growth and the pursuit of stability within the uncertain colonial environment. Bridie’s evolution from a street-smart girl to a woman contemplating her future reflects the broader theme of transformation and survival.

Luke

Luke, a gardener and former convict, represents a pragmatic but honorable figure in Kate’s new life. His history of hardship and rebellion resonates with Kate’s own struggles, and his vision of building a farm offers her a tangible hope for stability.

Their relationship, founded less on passionate love and more on companionship and mutual respect, exemplifies a mature form of partnership forged by necessity and survival. Luke’s loyalty and support provide Kate with a grounding presence amid the chaos of colonial Australia.

His character challenges traditional romantic ideals, emphasizing resilience and partnership as forms of love.

Nathaniel Harte

Dr. Nathaniel Harte is a pivotal male figure whose kindness and professionalism contrast with the harsh matrons and many other adults in Kate’s world.

His complicated relationship with Kate—marked by past affection, unfulfilled love, and eventual engagement to another woman—adds emotional complexity to her journey. Harte represents a connection to Kate’s inner world, her hopes for love and healing, and the tensions between personal desires and social realities.

His care for injured and ill orphans like Lizzie also highlights a humane aspect within a brutal system.

Lizzie and Sheila

Lizzie and Sheila are emblematic of the tough, street-smart women who survive the hardships of indenture and colonial life. As businesswomen in Bathurst, they have escaped their difficult pasts and carved out a place of independence in the gold rush economy.

Lizzie’s tragic experiences, including a secret pregnancy and self-harm, expose the vulnerabilities underlying their toughness. Together, they offer Kate a sense of community and a model of female empowerment through resilience and entrepreneurship.

Malachy and Phineas

Malachy and Phineas, former convicts and farm workers, provide a sense of camaraderie and practical support to Kate and Luke in the Outback and at the goldfields. Their colorful personalities and loyalty offer moments of warmth and humor amid adversity.

They symbolize the complex social fabric of colonial Australia, where people with difficult pasts could reinvent themselves and contribute meaningfully to new communities.

Themes

Survival and Resilience

The narrative of The Famine Orphans captures survival not only as a physical act but as an ongoing emotional and psychological battle. From the initial devastation of the Great Irish Famine, survival takes on the shape of enduring hunger, sickness, and loss of family and home.

The harsh realities of starvation and eviction force Kate and her family into the workhouse, a place symbolic of desperation but also a crucible where resilience is forged. Survival here extends beyond mere sustenance; it is about maintaining dignity, hope, and human connection in the face of crushing despair.

As Kate and the other orphans endure the grueling journey to Australia aboard the Sabine, survival demands endurance through illness, seasickness, fear, and emotional trauma, while also navigating the rigid discipline imposed by matrons and the constant uncertainty of their futures. The long voyage is marked by the orphans’ determination to keep their spirits alive through learning, communal singing, and mutual support, which underscores resilience as a collective, as much as individual, experience.

Later, survival evolves into adaptation in a new and often hostile land where Kate confronts social prejudice, economic hardship, and the challenge of rebuilding a life from scratch. Her decision to accept Luke’s companionship is an act of survival grounded in pragmatism and dignity rather than romance.

Even when she ventures into the goldfields, survival takes the form of boldness and resourcefulness, where success depends on grit and mutual aid among outcasts and friends. The theme underscores how resilience grows not from ideal conditions but through persistent courage, community, and the refusal to surrender identity or hope despite relentless adversity.

Displacement and Identity

Displacement in The Famine Orphans is both physical and existential, shaping the characters’ sense of self and belonging. Kate’s journey begins in a deeply rooted rural Irish community, where land, family, and religion form the core of identity.

The sudden rupture caused by famine severs these roots and forces her family into unfamiliar and often hostile environments, from the workhouse to the harsh reality of enforced migration. Being uprooted from Ireland means more than losing a homeland; it means confronting a profound identity crisis.

On the ship, the girls are suspended between worlds — caught between a tragic past and an uncertain future, struggling to preserve their Irishness while adapting to the foreign culture and expectations imposed by their British overseers. Once in Australia, displacement manifests in the social hierarchy that marginalizes them as unwanted Irish orphans, viewed with suspicion and disdain by colonial society.

Kate’s resistance to these judgments and her defense of her community highlight a fight to retain cultural pride and individual dignity amid discrimination. Throughout her experiences—from domestic service to marriage, then to the goldfields—Kate’s evolving sense of self reflects the tension between adaptation and the preservation of origins.

Her eventual embrace of a new life in the Outback, alongside former convicts and fellow immigrants, represents a redefinition of identity forged from shared struggle rather than traditional roots. Displacement in the story is thus a force that fractures but also reshapes, compelling characters to negotiate who they are in relation to place, community, and history.

Social Injustice and Class Conflict

The harsh realities of class and social injustice permeate The Famine Orphans, revealing the brutal inequalities that define both Ireland during the famine and colonial Australia. The tenant farming system, dependent on potato crops controlled by landlords, sets the stage for economic vulnerability and exploitation.

Kate’s family’s eviction reflects the cold priorities of landlords like Charles Smythe, who prioritize rent over human suffering, exposing the systemic cruelty faced by the rural poor. The workhouse is emblematic of institutional neglect and the social stigma attached to poverty, where overcrowding and disease illustrate the state’s failure to protect its most vulnerable.

Emigration itself, framed as a “solution,” is tinged with paternalism and control, offering escape but stripping agency. Upon arrival in Australia, the orphans encounter another layer of social prejudice.

They are stereotyped as morally suspect and unfit for decent work, reflecting broader ethnic and class-based discrimination within the colonial hierarchy. Kate’s confrontation with powerful men at Mrs.

Pitt’s garden party reveals the entrenched elitism and hostility that immigrant women face. Even within their own community, struggles over survival and respect unfold, as the girls navigate indenture, domestic labor, and the harsh realities of economic dependency.

The goldfields sequence further exposes class tensions, with prospectors, business owners, and former convicts carving out a rough, competitive existence where social status is fluid but fraught. This theme highlights the intersection of poverty, ethnicity, and gender, revealing how injustice shapes every aspect of the characters’ lives and survival.

Female Solidarity and Community

Throughout The Famine Orphans, the strength of female solidarity emerges as a vital source of comfort, resistance, and survival. From the earliest hardships in Ireland through the journey and settlement in Australia, the orphans form bonds that transcend the immediate challenges they face.

The relationships between Kate, Bridie, Patsy, Lizzie, and others provide emotional sustenance and practical support in an environment where trust is scarce and betrayal common. The shipboard community serves as a microcosm where teaching, sharing, and mutual care help the girls endure hardship and loneliness.

Despite moments of tension and conflict, the girls find strength in collective rituals such as singing and shared learning. Later, in colonial society, female alliances continue to provide a counterbalance to social exclusion and oppression.

Kate’s role as a teacher and later as a school founder symbolizes the transformative power of women empowering each other through education and leadership. The narrative also explores complex female experiences of trauma, such as Lizzie’s pregnancy and Patsy’s descent into prostitution, handled with empathy and depth.

These experiences underline how survival is not solitary but communal, forged through networks of care and resistance. Female solidarity becomes a means of reclaiming agency, preserving culture, and building new futures in a world marked by hardship.

Hope and Transformation

Amidst the bleakness of famine, displacement, and prejudice, The Famine Orphans is deeply invested in the theme of hope as a driving force toward transformation. Hope is never naïve or abstract but rooted in concrete actions and aspirations that propel Kate and her companions forward.

The promise of emigration, though fraught with uncertainty, symbolizes a break from death and despair toward potential renewal. Throughout the narrative, moments of beauty—such as the orphans’ songs, the friendships they forge, and small acts of kindness—offer glimpses of possibility.

Kate’s decision to learn, teach, and eventually seek independence reflects a commitment to change her circumstances rather than succumb to victimhood. The gold rush episode epitomizes hope turning into tangible opportunity, where risk-taking and perseverance yield material success and social mobility.

Even Kate’s pragmatic marriage to Luke is shaped by the hope for stability and dignity rather than romantic idealism. The story’s closing scenes of community building, education, and rekindled love underscore transformation as ongoing and multifaceted.

This theme emphasizes that amid loss and displacement, hope can ignite resilience and redefinition, allowing individuals and communities to reclaim agency and build futures on their own terms.