The Fourth Daughter Summary, Characters and Themes

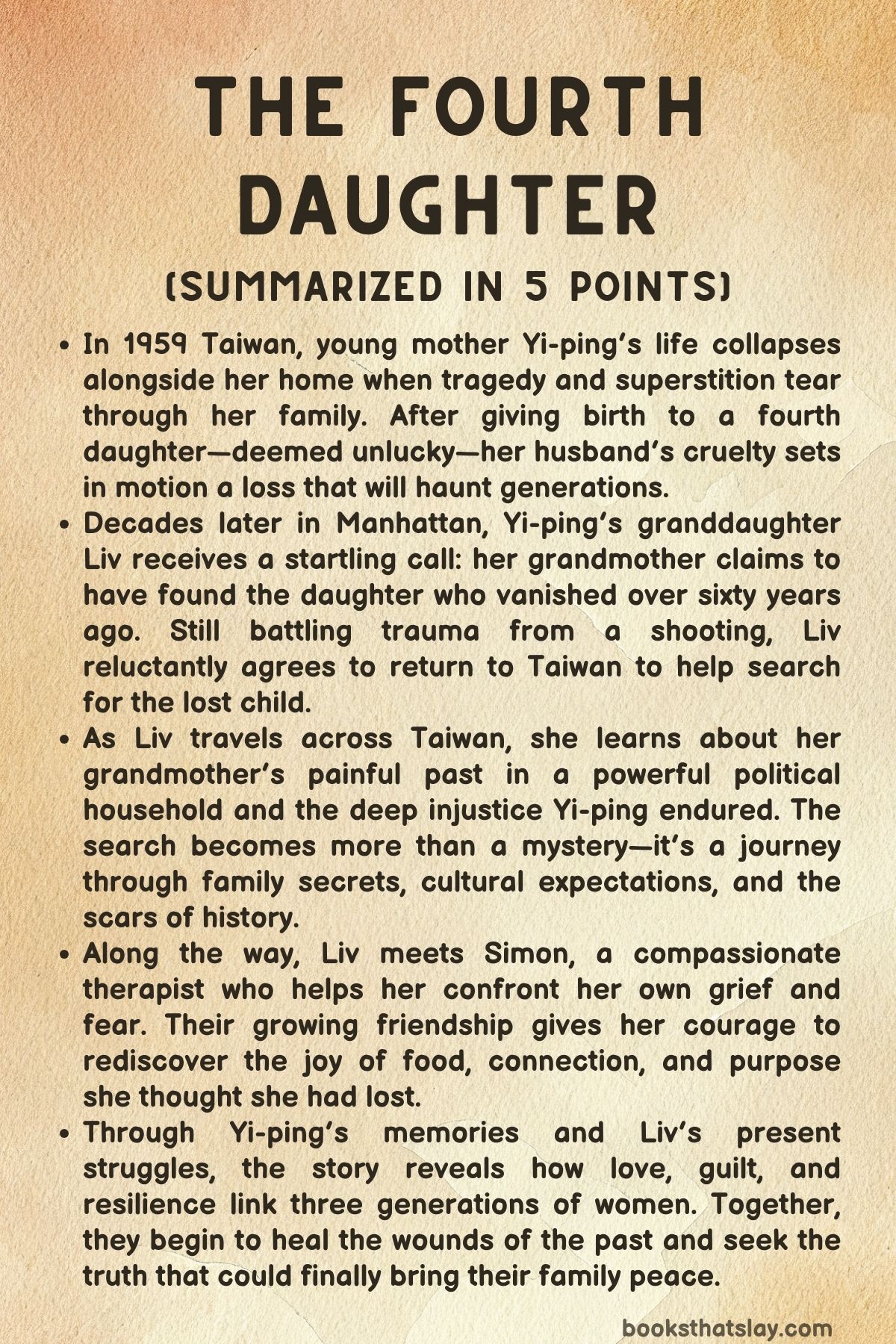

The Fourth Daughter by Lyn Liao Butler is a multigenerational story that moves between 1950s Taiwan and modern-day New York, exploring family secrets, political upheaval, and the enduring strength of women. It follows Yi-ping, a young Taiwanese mother trapped in a rigid, patriarchal world, and her granddaughter Liv, a Manhattan chef scarred by personal trauma.

When Liv learns of her grandmother’s long-lost daughter—stolen during Taiwan’s martial law era—their intertwined journeys of loss, discovery, and reconciliation unfold. Through cultural and emotional contrasts, Butler captures how history, motherhood, and courage can bridge generations and bring healing after decades of silence.

Summary

In 1959 Taiwan, Yi-ping’s life collapses both literally and emotionally when her home near Taichung crumbles during dinner. Though she saves her family, the event marks the beginning of a series of calamities.

Her father-in-law is blinded, a young nephew dies, and when her fourth child is born a girl instead of the son her husband wanted, she faces contempt rather than joy. Her husband, Po-wei, calls the baby cursed because the number four sounds like “death” in Chinese.

Yi-ping loves the baby, named Yili, but her husband’s rejection foreshadows tragedy.

Decades later, Yi-ping’s granddaughter Liv answers a FaceTime call from her eighty-six-year-old grandmother in Taiwan. Yi-ping claims she has just seen her missing fourth daughter, the child Liv never knew existed.

Yi-ping explains that her husband stole the baby when she was eighteen months old, and she has searched for her ever since. Convinced she recognized her grown daughter at a food stall by a small birthmark, she pleads with Liv to come to Taiwan.

Liv, who has been reeling from trauma after surviving a shooting at her Manhattan restaurant, feels trapped in her grief and anxiety. The plea from her grandmother stirs something in her—a reason to face the world again.

Yi-ping’s memories return to 1961, when she finally gave birth to a son after years of producing daughters. The powerful Wang family celebrated the birth lavishly, but the joy ended abruptly when her daughter Yili disappeared during the party.

Her husband returned and coldly told her the girl was “safe,” refusing to reveal where she was. Yi-ping’s mother-in-law demanded silence, warning her that children belonged to their father and that defiance would bring ruin.

Heartbroken and powerless, Yi-ping vowed to find her missing child.

In the present, Liv decides to travel to Taiwan to help. Her mother, Felicia, confirms the story and reveals that their family’s past was tied to Taiwan’s authoritarian KMT regime, which made people disappear.

Liv learns of the silence that shrouded Yili’s memory and flies to Taiwan, where she meets Simon Huang, a kind stranger who comforts her during a panic attack at the airport. He is a psychotherapist, and their brief encounter plants the seed of connection.

Upon arriving, Liv reunites with her grandmother, Ah-Ma, sharing warm meals and memories that blend nostalgia with sadness.

Ah-Ma recounts how, after Yili vanished, she tried desperately to regain her family’s favor while secretly searching for her daughter. Her husband’s family had given Yili to another family, the Ongs, to be raised as a future bride for their son—a common yet cruel custom.

Despite warnings, Yi-ping tried to trace the Ongs but failed. During this time, she met a kind neighbor, Lim Ziyi, who supported her emotionally and helped her investigate.

Ziyi revealed that Yi-ping’s husband had been involved in political arrests under Taiwan’s White Terror, making her search dangerous. Even as Ziyi faced her own abusive marriage, she risked her safety to help Yi-ping.

In the modern timeline, Liv and Ah-Ma retrace old streets, eat from night markets, and begin posting about Yili online. Liv also opens up about the shooting that left her with trauma.

Simon reappears, helping Liv with her panic attacks and encouraging her to continue the search. Together they rediscover hope while exploring Taiwan’s landscapes and food.

Ah-Ma shows Liv a box of keepsakes belonging to Yili and tells her she started recording recipes after her daughter’s disappearance, believing that cooking her favorite dishes might somehow bring her home. Liv records them cooking together and shares it online, reconnecting with her passion for food.

Ah-Ma introduces Liv to Ziyi, now elderly and living in a quiet estate with her companion Ah-Ji. Ziyi recounts how she once helped Yi-ping escape Taiwan’s oppressive regime by forging travel documents.

When her husband discovered this, he beat her and exiled her to a remote village, threatening her family. She later revealed that she poisoned him to save herself and her daughter.

Ziyi then devoted her life to women’s rights. Hearing her story, Liv begins to understand the extent of the courage and suffering in her grandmother’s generation.

When Ah-Ma’s DNA results arrive, they reveal a potential match with a woman named Hsu-Min Chen. The name shocks Simon—he knows her as the aunt of his late friend.

Hsu-Min’s family name connects her to Clare Shih, a woman Liv had previously met who reacted with hostility upon hearing her grandfather’s name. Clare’s family had suffered under the KMT, the same regime her grandfather served.

The revelation uncovers decades of tangled history linking both families.

Flashbacks reveal that in 1961, Ang-Li, Clare’s father, and his wife Jin adopted a baby girl named Yili, who became Hsu-Min. Jin had been Po-wei’s former lover, and her jealousy and grief led her to take Yi-ping’s child.

When Jin was later executed under false charges, Ang-Li fled Taiwan with the children, raising them in America while concealing the truth to protect them. Yili grew up as Sue Chen, unaware of her origins.

In the present, Clare discovers her father’s journals, learning of his ties to both the Wangs and her mother’s death. Struggling with anger and guilt, she returns to Taiwan, watching Yi-ping (Ah-Ma) from afar and resenting her.

But when Liv’s search exposes the truth, Clare finally confronts the past. She visits Ah-Ma and apologizes for years of silence.

Just then, Sue arrives—Yi-ping’s lost daughter, now an older woman. The long-separated mother and child embrace, their reunion filled with emotion and forgiveness.

Sue recalls dreams of a woman she never knew was real, recognizing Ah-Ma as that figure.

A celebratory family dinner follows, bringing together generations of Wangs, Shihs, and Huangs. Liv, Simon, Ah-Ma, and Sue share laughter, food, and stories.

But when a loud noise triggers Liv’s trauma, her family supports her through it, reminding her she’s not alone. Gradually, she accepts the need for therapy and healing.

Later, Ah-Ma and Liv read Ang-Li’s journals, discovering that he regretted misunderstanding Yi-ping and had left a letter from Sue as a child. Sue later returns the letter, expressing her longing for the mother she never knew.

In that moment, Yi-ping finally feels whole.

As the story closes, Liv and Simon commit to a future together in Taiwan, Ah-Ma finds peace after decades of grief, and three generations of women—once fractured by secrecy and politics—stand reunited. Through love, forgiveness, and the rediscovery of family, they reclaim their shared identity and honor the lost daughter whose absence defined their lives.

Characters

Yi-ping (Ah-Ma)

Yi-ping stands as the emotional and moral center of The Fourth Daughter, embodying resilience, maternal devotion, and the scars of patriarchal oppression. As a young woman in 1950s Taiwan, she lives within the suffocating expectations of a patriarchal society that values sons over daughters.

Her life begins to unravel when her fourth child—another daughter, Yili—is deemed cursed and taken from her by her husband. This traumatic loss defines her life, and her relentless search for Yili across six decades transforms her from a submissive wife into a symbol of quiet rebellion.

In her later years, as Ah-Ma, Yi-ping’s strength is tempered by wisdom and empathy. She has survived political turmoil, loss, and emotional desolation, yet remains deeply loving.

Through her bond with her granddaughter Liv, she transmits not just the story of her missing daughter but also the endurance of maternal love that transcends time and tragedy.

Liv Wang

Liv, Yi-ping’s granddaughter, represents the modern continuation of her grandmother’s courage. Living in contemporary Manhattan, she battles severe trauma after surviving a mass shooting that upended her life and career as a promising sous-chef.

Her paralysis—both emotional and physical—mirrors her grandmother’s early entrapment within the confines of duty and loss. When Yi-ping calls her to Taiwan to search for the missing fourth daughter, Liv’s journey becomes not only an external quest but an internal healing.

She reclaims her sense of purpose and agency through connection with her heritage, food, and love. Liv’s evolution from fear to empowerment mirrors the generational healing at the heart of the novel.

She becomes the bridge between past and present, reconnecting fractured histories through compassion and courage.

Wang Po-wei

Po-wei, Yi-ping’s husband, embodies the patriarchal authority that crushes individuality and compassion under the weight of status and tradition. A member of Taiwan’s ruling Kuomintang elite, he is both privileged and emotionally impoverished.

His obsession with having a son—and his cruel rejection of his fourth daughter—reflects how societal values warp human relationships. Though outwardly powerful, his actions are driven by insecurity, political ambition, and inherited misogyny.

Over time, his moral decay isolates him, and his eventual death, marked by belated remorse, underscores the hollow cost of power untempered by empathy. Through him, the novel exposes the generational damage inflicted by patriarchal and political oppression.

Felicia Wang

Felicia, Yi-ping’s third daughter and Liv’s mother, exists in the emotional liminal space between her mother’s pain and her daughter’s modern life. Having grown up under the shadow of her father’s dominance and her mother’s grief, Felicia represents the legacy of silence passed through generations of women.

Her partial memories of her missing sister, Yili, and her restrained demeanor reveal a woman conditioned by trauma and cultural displacement. Moving to America provided her physical freedom but did not fully sever her emotional ties to her family’s tragic past.

Felicia’s quiet presence in the novel reinforces the theme of inherited pain, suggesting that healing requires not only distance but confrontation with memory.

Yili (Sue / Hsu-Min Chen)

The titular “fourth daughter,” Yili’s life encapsulates the consequences of stolen identity and forced separation. Taken from her mother and renamed Hsu-Min, she is raised under another family’s legacy of political suffering.

Her existence as a “shim-pua” child bride, her repressed memories, and her eventual rediscovery give shape to the novel’s themes of lost heritage and reclamation. When she finally reunites with Yi-ping, their embrace signifies the triumph of love over history’s cruelties.

Yili’s dual identity—as both victim and survivor—bridges two families divided by politics and time. Her forgiveness and acceptance in the end close a generational wound that began with her disappearance.

Clare Chen

Clare’s character is a complex portrait of bitterness, ideology, and redemption. As Yili’s adopted sister and Ang-Li’s daughter, she grows up carrying the weight of Taiwan’s political terror and her parents’ tragic history.

Her hostility toward Liv and Ah-Ma springs from deep-seated grief and misunderstanding—believing Yi-ping’s husband’s regime destroyed her family. Clare’s eventual reconciliation with Ah-Ma and Liv symbolizes the necessity of confronting buried truths to achieve healing.

Her transformation from a woman hardened by ideology into one open to forgiveness mirrors Taiwan’s broader reckoning with its past.

Ziyi Lim

Ziyi serves as Yi-ping’s friend, confidante, and mirror image—a woman of refinement trapped in her own abusive marriage. Her intelligence and empathy drive her to help Yi-ping, even at immense personal risk.

Ziyi’s story of survival—enduring exile, domestic violence, and moral compromise—adds another layer to the novel’s exploration of women’s endurance. Her later confession to poisoning her husband is both shocking and tragic, revealing the extremes women may be driven to in their pursuit of freedom.

Despite her darkness, Ziyi remains a figure of compassion, devoting her later life to protecting women’s rights, embodying the novel’s belief in redemption through solidarity and courage.

Simon Huang

Simon acts as the emotional anchor for Liv in the modern timeline, his calm empathy contrasting her panic and disorientation. As a psychotherapist specializing in trauma, he becomes both guide and companion, helping Liv confront her fears.

His own connection to Taiwan’s past—through his family’s ties to those affected by KMT oppression—links him intimately with Liv’s story. His love for her grows naturally from shared vulnerability, and his decision to remain in Taiwan symbolizes a commitment to healing, both personal and collective.

Simon’s presence reinforces the novel’s intergenerational theme: that understanding and compassion can bridge even the deepest wounds.

Ang-Li Chen

Ang-Li is a tragic figure whose life is defined by political persecution, loss, and remorse. Once a man of ideals, he becomes ensnared in Taiwan’s White Terror, losing his wife to execution and fleeing with an adopted child—unaware she was the stolen Yili.

His journal later reveals his anguish and guilt, offering insight into a man broken by history but striving to do right in exile. Through Ang-Li, The Fourth Daughter reveals the moral complexity of survival under authoritarianism and the way ordinary people become both victims and unwilling participants in systemic cruelty.

His legacy, preserved through his writings, becomes a vehicle for truth and reconciliation among the next generations.

Jin Ong

Jin, the adoptive mother of Yili, is both villain and victim—a woman who, motivated by love, jealousy, and political desperation, adopts Yili under false pretenses. Her execution as a supposed spy seals the fate of her fractured family and sets in motion the tangled web of connections that drive the novel.

Jin’s actions blur moral boundaries, suggesting that even destructive choices can emerge from the chaos of oppression and survival.

Ah-Ji

Ah-Ji, Ziyi’s loyal servant and companion, represents devotion and quiet strength. She stands by Ziyi through exile, abuse, and rebellion, sharing her isolation and aiding her in both nurturing life and enacting vengeance.

Through Ah-Ji, the novel honors the invisible women who bear the weight of others’ suffering with dignity and courage.

Themes

Patriarchy and the Struggle for Female Autonomy

Across generations, The Fourth Daughter portrays the suffocating weight of patriarchal control and the enduring female fight for independence. Yi-ping’s life in 1950s Taiwan is defined by the authority of men—her husband, his family, and a culture that assigns worth to women only through their ability to bear sons.

Her husband’s rejection of their fourth daughter and his unchallenged power to decide the child’s fate represent a broader system that denies women agency over their bodies, children, and choices. This loss is not only personal but systemic—every decision Yi-ping makes is governed by fear of male authority and the social order it enforces.

Her evolution from a submissive wife to a woman determined to search for her lost child defies the rules imposed on her, even if it takes her decades to achieve peace. Liv, her granddaughter, inherits a world with different freedoms but faces her own psychological confinement, shaped by trauma and self-doubt.

Through her, the novel suggests that female autonomy is not a singular act of rebellion but an ongoing reclamation—one that spans generations. Yi-ping’s defiance plants the seeds of strength that allow Liv to eventually confront her fears and find purpose.

In both women, the narrative highlights how breaking free from patriarchal expectations requires not only courage but healing from the silence and shame those systems impose.

Generational Trauma and Healing

The novel’s emotional core lies in the transmission of pain across generations and the quiet resilience that follows. Yi-ping’s grief and guilt over her missing daughter become a shadow that hovers over her descendants, shaping the emotional landscape of her family even decades later.

The trauma of political fear, domestic abuse, and personal loss manifests differently in each generation—Yi-ping through grief, Felicia through emotional distance, and Liv through crippling anxiety and isolation. Liv’s post-traumatic paralysis following the shooting in New York is not merely a contemporary crisis but echoes her grandmother’s unhealed wounds.

Their intertwined journeys show that trauma does not vanish with time; it transforms, hiding in habits, fears, and silences. When Liv travels to Taiwan and reconnects with her grandmother, their shared pain becomes the bridge that allows healing to begin.

The act of storytelling—Yi-ping recounting her past, Liv cooking her grandmother’s recipes—becomes therapy in motion. Through these rituals, the family begins to reclaim lost narratives and reframe pain as legacy rather than curse.

The reunion of Yi-ping and her long-lost daughter Yili is not only a personal closure but also symbolic of intergenerational repair—a testament that even the deepest familial wounds can begin to mend when truth replaces secrecy.

The Weight of Tradition and Superstition

In The Fourth Daughter, cultural beliefs and superstitions act as both a moral compass and a cage. The birth of Yi-ping’s fourth daughter, branded unlucky because the number “four” sounds like “death” in Chinese, reveals how traditions can justify cruelty under the guise of fate.

Her husband’s insistence that the baby is cursed allows him to abandon his moral responsibility while appearing faithful to cultural norms. The novel portrays how superstition intertwines with social hierarchy, dictating the lives of women who are already powerless under Confucian family structures.

Even decades later, these inherited beliefs shape family behaviors—Liv’s mother still avoids speaking of the lost child, as if acknowledging her would invite misfortune. Yet the same traditions that restrict also provide continuity and identity.

The rituals of food, mourning, and remembrance connect generations across continents and eras. Liv’s rediscovery of her grandmother’s recipes turns superstition into art, reclaiming it from fear and transforming it into an act of love.

Through this evolution, the novel suggests that tradition need not vanish but can be reinterpreted, shifting from an oppressive code to a vessel for connection and meaning.

Political Oppression and Moral Complicity

The backdrop of Taiwan’s martial-law era, known as the White Terror, gives the story a political depth that mirrors the personal injustices of the characters. The Wang family’s involvement in the Kuomintang elite grants them privilege but also traps them in a system built on silence and complicity.

Yi-ping’s husband participates in the arrests and torture of political dissidents, using his power to conceal the family’s private sins, including the disappearance of his daughter. The novel illustrates how political and domestic tyranny are reflections of each other—both thrive on control, secrecy, and fear.

For women like Yi-ping and her friend Ziyi, survival requires submission in public but quiet rebellion in private. Their resistance takes covert forms: Ziyi’s act of helping others escape persecution, Yi-ping’s secret search for her child, and even the later confession of Ziyi’s act of vengeance against her abusive husband.

These are moral responses to a world that offers no justice. Through the multigenerational narrative, Butler exposes how political violence seeps into families, reshaping their loyalties and ethics.

The novel compels readers to consider how systems of power—state or familial—demand silence, and how truth-telling becomes the most radical form of resistance.

Identity, Memory, and Reconnection

The search for Yili and the rediscovery of her identity as Sue form the emotional resolution of The Fourth Daughter, tying together the themes of loss, belonging, and reconciliation. For Yi-ping, the missing daughter symbolizes the part of herself taken by patriarchy and silence.

For Liv, the search is a way to rebuild her fractured sense of self after trauma. Their journeys mirror one another—both women are lost and searching for a reason to live.

The novel portrays identity as something fluid, shaped by time, migration, and memory. Yili grows up as Hsu-Min Chen, unaware of her true origins, while Yi-ping spends her life defined by the absence of that truth.

When the DNA test and social media finally bridge the decades-long divide, technology becomes the modern counterpart to oral memory—a new way of restoring lost histories. The reunion of mother and daughter, and the coming together of both families, demonstrates that identity is not bound solely by blood but by shared acknowledgment of pain and forgiveness.

Through this reconnection, the novel closes its long arc of displacement and secrecy, showing that healing begins when people choose to confront rather than conceal their truths.

Food as Memory and Rebirth

Food serves as the emotional language of The Fourth Daughter, a conduit through which generations communicate love, memory, and identity. For Yi-ping, cooking becomes both an act of devotion and a means of survival after Yili’s disappearance.

Her handmade cookbook represents an unspoken prayer—that through recipes, her daughter might one day find her way home. For Liv, rediscovering these dishes revives her will to live after the trauma that left her paralyzed.

The act of cooking with her grandmother rekindles a connection not just to family, but to herself, transforming culinary art into emotional recovery. Each meal shared between characters carries layers of meaning: repentance, remembrance, and renewal.

Food transcends its domestic role, becoming a metaphor for creation in the face of destruction. It allows the women of the novel to define themselves outside patriarchal control and trauma, to nurture and rebuild rather than be consumed by grief.

In the final reunion feast, where the families gather around a table filled with laughter and shared dishes, food becomes the ultimate symbol of reconciliation—a living archive of heritage, forgiveness, and rebirth that unites the past and present into a single, healing moment.