The Frozen River Summary, Characters and Themes

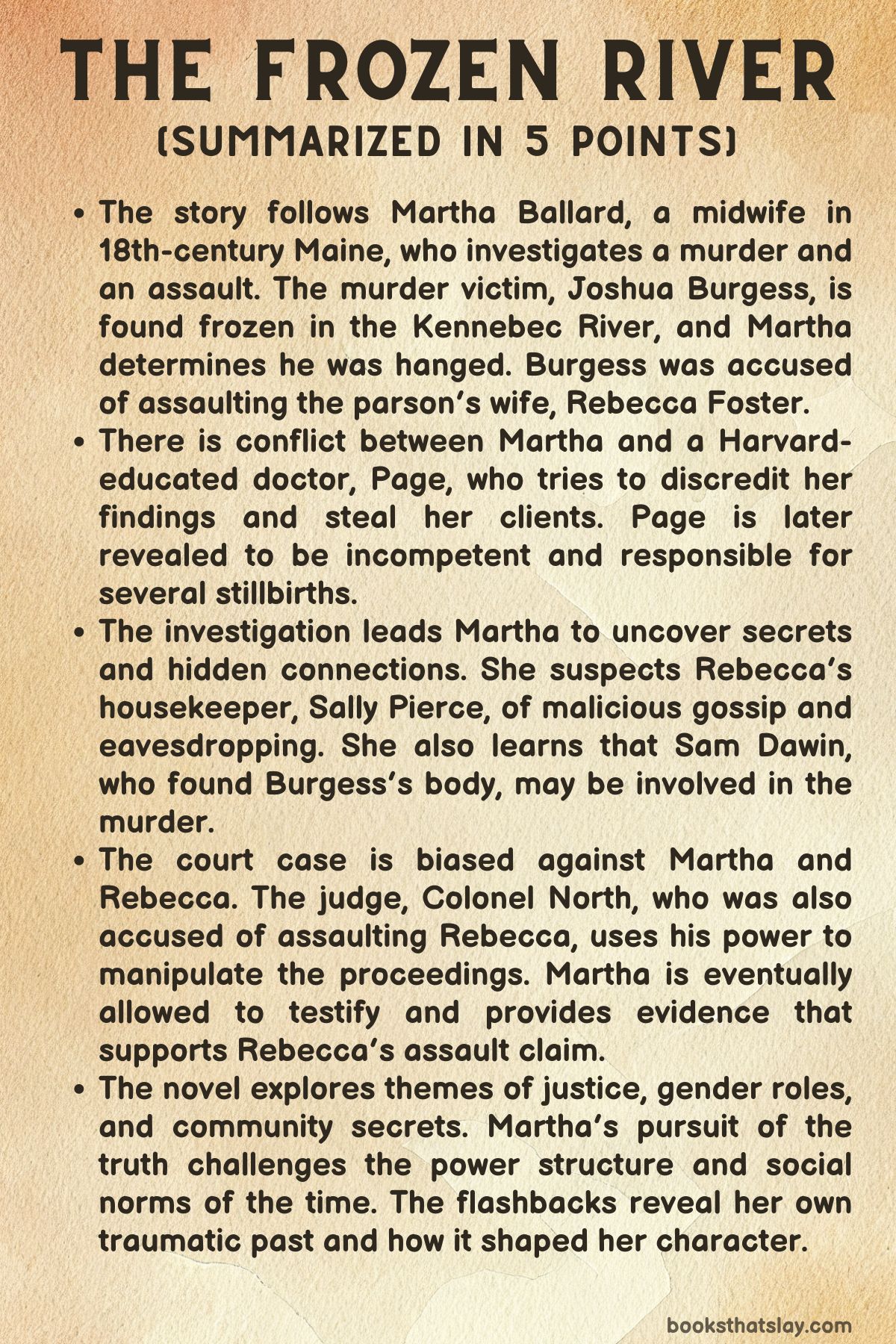

The Frozen River by Ariel Lawhon is a historical fiction novel set in 1789 Maine, following Martha Ballard, a midwife, healer, and sharp observer of human nature.

She finds herself pulled into a murder investigation after a body is discovered frozen in the Kennebec River, while also navigating the fallout from a brutal rape that has shaken her small Puritan community. Drawing from real entries in Martha’s journals and layered with imagined conflicts, the book explores how Martha balances her family’s safety, her duty as a midwife, and the relentless expectations of a town that often undervalues women’s voices. This story brings to life themes of power, gender, community secrets, and the quiet strength of one determined woman.

Summary

During a harsh winter in Maine, a dead body is found frozen in the Kennebec River near Hallowell, catching the town’s attention. Martha Ballard, the local midwife, is called to examine the body, which turns out to be Joshua Burgess.

He had been accused of raping Rebecca Foster, the parson’s wife, and there are many who might have wanted him dead. Martha’s examination reveals that Burgess was hanged and beaten before being thrown into the river, but Dr.

Page, a newcomer, disputes her findings, claiming the death was accidental.

While handling births and tending to the sick, Martha becomes aware of the layers of injustice surrounding her. She sees the societal cruelty toward women who have children out of wedlock, the heavy silence around sexual violence, and the hypocrisy of men who wield power while committing terrible acts.

Her work puts her close to the town’s women, where she hears their secrets and witnesses the pain many of them carry in a world that gives them little protection.

Martha’s personal life weaves into these tensions. Her husband, Ephraim, is sent on a surveying job by Joseph North, the local judge who was also accused of raping Rebecca.

Martha realizes North’s absence of integrity and understands that the job was a tactic to keep Ephraim away from court, hoping to silence Martha’s testimony. When Ephraim returns in time for the hearing, Martha is allowed to testify, affirming Rebecca’s injuries and offering her journals as evidence.

Despite their efforts, North is acquitted of the charges, leaving Martha frustrated with a system that favors the powerful over the truth.

As the investigation around Burgess’s murder continues, suspicion falls on Martha’s mute son, Cyrus, due to an earlier altercation with Burgess. The community begins to fracture under gossip and courtroom conflicts.

Meanwhile, Martha continues her midwifery work, assisting births, comforting grieving mothers, and navigating the challenges of her profession in a male-dominated society.

Martha discovers that Sam Dawin, who found Burgess’s body, had a personal motive: Burgess had raped Sam’s wife, May, and kept a piece of her dress as a trophy. Sam, with the help of Martha’s son Jonathan, killed Burgess to protect May and to reclaim her dignity.

Understanding the violence that led to this murder, Martha chooses to protect Sam and Jonathan, recognizing the flawed justice in a world where the legal system often fails women.

Martha also navigates the personal challenges of her children’s lives, including Jonathan’s relationship with Sally Pierce, who becomes pregnant, and Martha’s hope to arrange a match between her son Cyrus and Sarah White, a young woman learning to read under Martha’s guidance. She witnesses the quiet heroism and vulnerabilities in the daily lives of those around her.

Tension escalates when North attempts to rape Martha, only for her to defend herself by severing his penis with a woodworking blade. She saves his life while ensuring he will never harm another woman again.

Ephraim supports her, handling the aftermath by ensuring the safety of their family and their property, which North had been trying to take from them.

In the closing chapters, Martha takes in Rebecca Foster’s newborn, whom Rebecca wishes to abandon due to the circumstances of her conception. Martha, refusing to let the child die, brings her to Sarah to be cared for, continuing her commitment to preserving life and dignity where the world offers little.

The fox, often seen by Martha throughout the story, appears as a quiet sign of endurance and watchfulness, reminding Martha that she and her family are not alone in their struggle for justice and peace.

The novel closes with Martha observing the fox and its cubs, a symbol of new life and continuity. It echoes her quiet but steadfast resistance in a world built to silence women, showcasing how Martha’s daily acts of courage, love, and defiance become her own form of justice, protecting her family and community in ways the courts never could.

Characters

Martha Ballard

Martha Ballard, the town midwife of Hallowell, is the anchor of The Frozen River, embodying resilience, moral clarity, and the burdens of a woman navigating the intersections of domestic duty and public justice. Having endured the trauma of rape in her youth, the loss of three daughters to diphtheria, and the persistent hardships of winter in Maine, Martha carries both grief and strength into every decision she makes.

Her deep sense of justice propels her to stand up for Rebecca Foster against the powerful Colonel North, even when doing so places her own family at risk. Her midwifery work is not just a profession but an assertion of feminine authority in a male-dominated society, where she protects other women’s lives and dignity while asserting her expertise against incompetent men like Dr. Page. Her journal, a recurring motif, becomes a testament to the lives of the women she helps, her tool for accountability, and a quiet rebellion against a world eager to silence her.

Her connection with the silver fox, Tempest, evokes a spiritual symbolism of feminine wildness, watchfulness, and quiet power that underscores Martha’s journey of survival and justice.

Ephraim Ballard

Ephraim Ballard, Martha’s husband, is a steady, supportive presence, though constrained by the pressures of providing for the family and the precariousness of property rights in colonial Maine. His love for Martha is grounded in genuine respect, demonstrated by his promise not to pressure her sexually after her rape and his gift of a Bible and ink, encouraging her literacy and journaling.

Yet, Ephraim is not free from the anxieties of manhood in a patriarchal society, often forced to leave home for long surveying jobs, risking the family’s well-being to secure their land from the looming threat of North’s ambitions.

His quiet acts of support, such as arriving just in time for Martha’s testimony, carrying North’s severed penis to Rebecca Foster as an act of justice, and enduring the loss of their children alongside Martha, illustrate the layered tenderness and practicality that define his character, making him a partner rather than a patriarch in their shared survival.

Rebecca Foster

Rebecca Foster, the parson’s wife, embodies the harsh realities faced by women who survive sexual violence within a society eager to silence them. Her rape by Burgess and North places her at the center of scandal and gossip, forcing her to navigate pregnancy as a consequence of violence while enduring public shaming through false accusations of fornication.

Rebecca’s bravery is evident in her eventual testimony against North despite the immense personal risk, and her initial wish for her child to die is a raw portrayal of the trauma she experiences, reflecting the complexities of maternal ambivalence born from assault. Her refusal to raise her child, asking Martha to throw the baby into the river, underscores the depth of her psychological suffering, while her presence in the narrative becomes a powerful critique of the societal and legal failures that allow perpetrators to escape justice while punishing victims.

Colonel Joseph North

Colonel Joseph North is the embodiment of male power wielded with cruelty and entitlement, using his influence in Hallowell to manipulate land rights, silence accusations of rape, and maintain control over the community. His history of profiting from the murder and scalping of Indigenous people during war reveals the violent roots of his wealth and power, aligning his personal cruelty with colonial violence.

North’s attempt to rape Martha, followed by his castration at her hands, is a powerful reversal of power, and the preservation of his life afterwards ensures his enduring humiliation. North’s character is not merely villainous but serves as a representation of the impunity and structural violence of men who believe themselves untouchable within a system designed to protect them.

Cyrus Ballard

Cyrus Ballard, Martha’s son, is a figure of quiet strength and tragedy, rendered mute after surviving diphtheria, a disability that isolates him socially but does not diminish his longing for connection. His altercation with Burgess at the dance makes him a suspect in the murder investigation, and his inability to speak forces him to rely on written testimony, illustrating the additional barriers faced by the disabled in the pursuit of justice.

His tenderness, particularly in his silent affection for Sarah White, contrasts sharply with the brutality surrounding him, and his loyalty to his family is evident in his willingness to endure suspicion without complaint.

Jonathan Ballard

Jonathan, the eldest Ballard son, is caught between youthful irresponsibility and the pressures of adult accountability. His sexual encounter with Sally Pierce, leading to her pregnancy, and his eventual decision to marry her reflect a growing sense of responsibility, even as he grapples with fear and avoidance.

His involvement in the murder of Burgess, alongside Sam Dawin, reveals a darker, protective aspect of Jonathan, participating in vigilante justice to defend the women around him from further harm. Jonathan’s arc mirrors the turbulence of young manhood in a world with rigid gender expectations and the moral complexities of justice when institutional structures fail.

Sam Dawin

Sam Dawin, a young man entangled in the discovery and murder of Burgess, represents the community’s frustration with the failures of legal justice and the impulse toward vigilantism. His motivation for killing Burgess is rooted in a protective anger after discovering that Burgess raped May, Sam’s fiancée, and took a piece of her dress as a trophy, echoing Burgess’s treatment of Rebecca.

Sam’s willingness to take justice into his own hands, despite the risk of execution, underscores the book’s exploration of the limits of law and the desperation of communities under the threat of predatory men like Burgess.

Dr. Page

Dr. Page, a newcomer to Hallowell, symbolizes the dangers of male arrogance and incompetence cloaked in societal authority.

His reliance on dangerous treatments like laudanum during childbirth, his casual negligence during births, and his resentment towards Martha’s expertise create a stark contrast between him and Martha’s careful, informed care. Page’s forced reliance on Martha when his own wife gives birth, and his subsequent outburst, highlight his inability to learn from his mistakes, representing the broader patriarchal tendency to dismiss female expertise until it becomes indispensable.

Sarah White

Sarah White, a young mother navigating the stigma of having a child out of wedlock, serves as a reflection of the societal judgment women face regardless of the circumstances of their pregnancies. Her determination to care for her child while facing community gossip and her openness to learning to read under Martha’s guidance show her quiet resilience.

Her story intersects with the rape narrative when it is revealed that Burgess harassed her, further illustrating the pervasive threat of predatory men in the community. Her eventual reunion with Charlotte’s father, Henry Warren, who marries her, offers a small beacon of hope in a world heavy with injustice.

Themes

Gender, Power, and Female Agency

In The Frozen River, gender and power dynamics consistently shape Martha Ballard’s world, pressing her into the position of mediator, protector, and silent witness in a society structured to confine women’s choices. Martha’s role as a midwife is not merely a profession but a subtle resistance against male control over female bodies, a recurring reality demonstrated by Dr.

Page’s repeated interventions and the community’s blind trust in him despite his incompetence. When Martha asserts her authority in childbirth and insists on naming patients, she reclaims dignity for women who are often dehumanized by the men around them, as seen during Melody Page’s labor.

The narrative exposes how marriage, childbirth, and even widowhood are all stages at which a woman’s autonomy is threatened or manipulated under patriarchal authority. This theme expands further through Martha’s defense of women like Rebecca Foster and Sarah White, revealing how societal condemnation of female sexuality and perceived purity becomes a tool for controlling women’s bodies and reputations, often without regard for the violence they endure.

Martha’s careful documentation of these injustices in her journal becomes her quiet but resolute resistance, affirming female experiences as worthy of record and testimony, even when the courtrooms remain hostile to such truths. The repeated motif of savine tea as a dangerous abortive measure also highlights the limitations on women’s control over reproduction, while Martha’s decision to preserve Rebecca’s child and her nurturing of fragile female connections reflect the complexity of female solidarity in a world that prioritizes male authority over women’s lived experiences.

Justice and Corruption

Throughout The Frozen River, the justice system in Hallowell is depicted as a deeply flawed and corrupted institution, entangled with power, personal interests, and societal biases. The murder of Joshua Burgess and the rape case against Colonel North reveal how justice can be manipulated by those in power, with North’s authority shielding him from accountability while he systematically suppresses dissent.

The court hearings are marked by intimidation, bribery, and manipulation of testimonies, reducing justice to a game where truth becomes negotiable. Martha’s steadfast insistence on her findings during the autopsy against Dr.

Page’s false claims underscores the cost of telling the truth in a system eager to silence inconvenient voices, especially those of women. The wrongful suspicion cast on Cyrus due to his disability, and the readiness of the community to scapegoat him, reflect how prejudice seeps into the justice system, transforming it into a tool for reinforcing existing hierarchies rather than serving truth.

Additionally, the economic entanglements—North’s exploitation of debt to expand his control and the Kennebec Proprietors’ manipulation of property rights—reveal how justice is not only denied in the courtroom but in the everyday transactions that define survival in Hallowell. Even Martha’s clandestine protection of Sam and Jonathan after they take justice into their own hands to avenge May’s rape demonstrates how vigilantism arises as a desperate response when formal justice fails, leaving the community in a moral grey zone where true justice becomes a matter of personal resolve and quiet resistance.

Community, Surveillance, and Gossip

The constant watchfulness of the community in The Frozen River builds an atmosphere where privacy is nearly impossible, and reputations can be dismantled by a whisper. Hallowell operates as a closed ecosystem in which every birth, death, and transgression becomes the subject of speculation and judgment, maintaining social order through fear and compliance.

This surveillance is embodied by figures like Sally Pierce, whose eavesdropping ignites legal repercussions for Rebecca Foster, and by the clusters of gossiping women at Dr. Coleman’s store who police the sexual morality of others while hiding their own indiscretions.

The community’s collective gaze enforces behavioral norms, particularly on women, who face ostracization for perceived moral failures while men’s transgressions are often overlooked or justified. However, this same community also becomes a source of support in moments of crisis, with Martha moving seamlessly through homes to deliver children and tend to the sick, reinforcing the paradox of a society that judges harshly yet depends on collective care to survive the harsh conditions of the Maine winter.

The constant presence of the silver fox symbolizes this watchfulness while also hinting at a form of silent, protective observation that contrasts with the community’s punitive scrutiny. Martha navigates this landscape with careful diplomacy, understanding that the same networks that spread rumors can be leveraged to gather critical information and protect those she cares about, revealing how the dynamics of surveillance and gossip are both oppressive and instrumental for survival.

Violence, Trauma, and Healing

Violence, both physical and systemic, permeates The Frozen River, shaping characters’ lives and influencing their decisions in visible and invisible ways. Martha’s own history of sexual violence during her youth and her subsequent trauma, carried quietly into her marriage, mirror the violence Rebecca Foster endures and the generational weight of such experiences that women must bear.

The visceral depiction of Burgess’s beaten and hanged body serves as a stark reminder of how physical violence operates as a means of control and retaliation within the community, whether as punishment for crimes or as extrajudicial vengeance when the justice system fails. The repeated instances of pregnancy, miscarriage, and stillbirth present a subtler form of violence, illustrating how women’s bodies become battlegrounds for societal, medical, and personal struggles.

Martha’s role as a midwife becomes a counterbalance to this violence, as she provides a form of healing grounded in compassion and expertise, contrasting sharply with Dr. Page’s careless practices that endanger women’s lives.

However, healing is not always clean or simple; Martha’s support of Sam and Jonathan’s murder of Burgess represents a moral ambiguity where violence becomes a form of justice, challenging the notion of clear right and wrong. The persistent undercurrent of trauma—whether through childbirth complications, rape, or societal persecution—remains unresolved, but Martha’s dedication to her work and her family reveals a commitment to mending what can be mended, even within the limitations imposed by a violent and indifferent world.