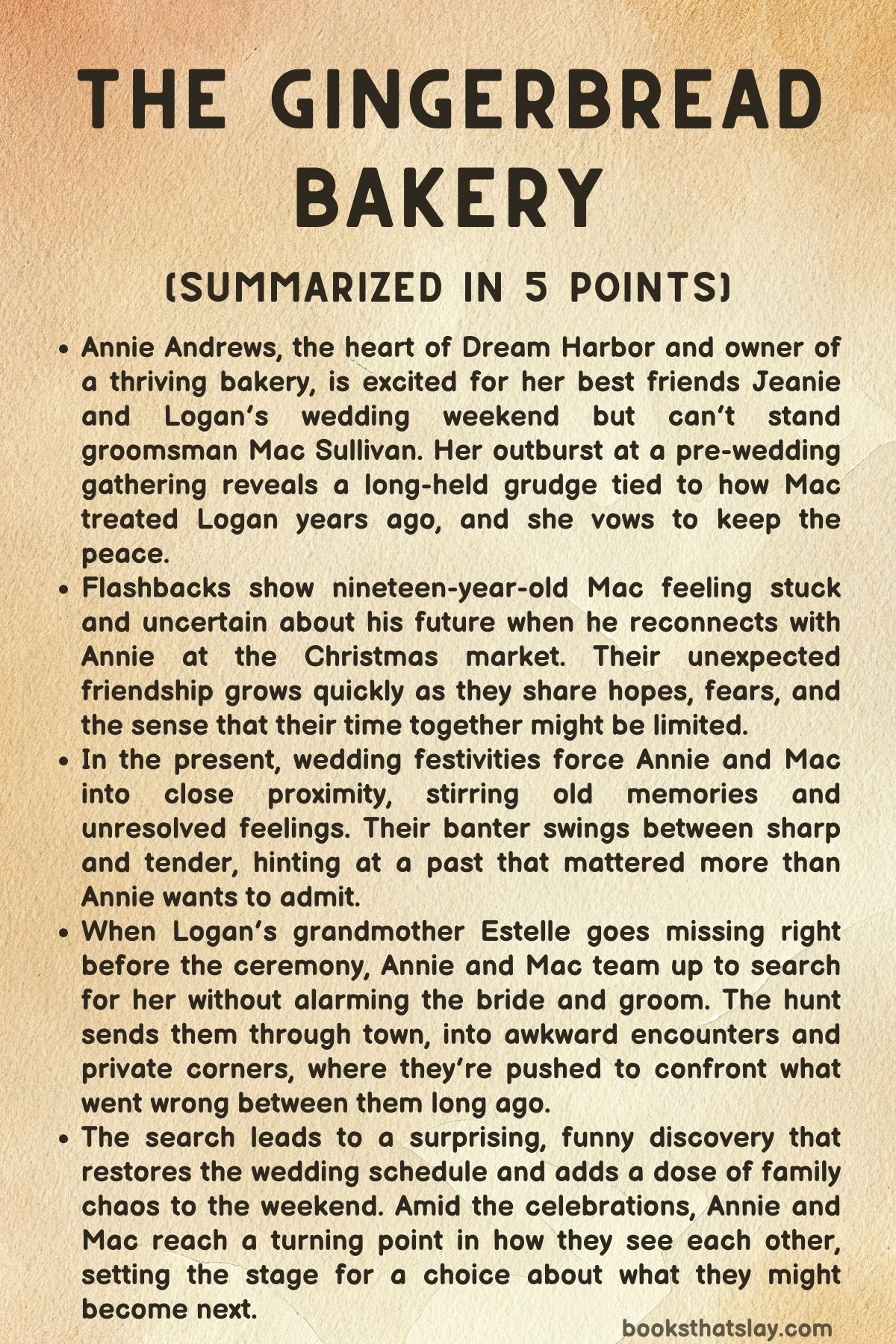

The Gingerbread Bakery Summary, Characters and Themes

The Gingerbread Bakery by Laurie Gilmore is a cozy, Christmas-season romance set in the small town of Dream Harbor. Annie Andrews, the town’s sunshine-bright baker, has built her life around her shop, her friends, and the rituals that make the harbor feel like home.

She believes in community and second chances—except when it comes to Mac Sullivan, a man tied to old hurts she’s never fully released. A winter wedding, a missing grandmother, and the pull of unresolved feelings force Annie and Mac to face who they were, who they are now, and what love might look like if they choose it on purpose.

Summary

Annie Andrews is one of Dream Harbor’s most reliable hearts. She owns a thriving bakery, supports her friends without hesitation, and keeps the town’s holiday spirit running on sugar and goodwill.

She likes nearly everyone, but she has never liked Macaulay “Mac” Sullivan. At a relaxed rehearsal brunch for her best friends Jeanie and Logan, Annie can’t hide her anger that Mac is a groomsman.

When Logan toasts his childhood friends, Annie blurts out that she objects to Mac standing beside him, accusing Mac of having bullied Logan as a child when Logan was grieving his mother. Jeanie is shaken, the table goes silent, and Annie scrambles to apologize.

She promises to keep herself in check for the wedding weekend, and Mac agrees to do the same. Even so, Annie feels furious that he is there at all.

Mac’s presence pulls both of them back to a Christmas long ago. Eleven years earlier, Mac was nineteen and feeling stuck.

He lived at home, worked at his father’s pub, and carried a quiet shame about not knowing what to do with his life. Wandering the Dream Harbor Christmas market, he planned to leave town after the holidays to drive across the country and try to find himself.

There he noticed Annie running a tiny stall of holiday cookies. She spoke with certainty about her dream of opening her own bakery and was already taking classes to make it real.

Mac bought her gingerbread, was surprised by how good it was, and impulsively asked her to meet him later at the diner. Annie, caught off guard but curious, agreed.

At the diner Mac asked why she seemed to dislike him. Annie told him plainly that she hated how he had teased Logan in elementary school during a painful time in Logan’s life.

The truth hit Mac hard. He apologized immediately and even texted Logan a sincere apology on the spot.

Logan accepted, and Annie decided to forgive Mac too. That night opened a door between them.

Over the next few weeks they spent time together at Christmas events, talking late, teasing each other, and sharing the kind of easy companionship they had never tried before. During the town’s Christmas lights tour, their closeness grew physical and sweet, ending with Annie going home with him.

The connection turned into a brief, intense relationship, but it was shadowed by Mac’s plan to leave after New Year’s. When he finally went, he didn’t say goodbye in the way Annie needed.

She was left hurt, embarrassed, and angry, and she folded the pain into a grudge she carried for years.

In the present, the official rehearsal takes place at Kira’s renovated barn on her Christmas tree farm. Logan is nervous about speaking at the ceremony, and Mac tries to steady him with humor, but he keeps watching Annie.

When they are paired to walk back down the aisle together, Mac tells her she looks beautiful. Annie cuts him off sharply and warns him not to mess with her head again.

At the rehearsal dinner, couples slow-dance under twinkle lights while Annie feels conspicuously single. For a moment, when the barn empties out and the lights soften everything, she and Mac drift into a slow sway that feels like the past breathing again.

Annie pulls away before it goes further.

The next morning a crisis interrupts wedding calm. Hazel calls Annie in a panic: Logan’s Nana Estelle has gone missing.

Hazel was supposed to take her to a hair appointment, but Estelle left early with Dot on a secret errand. Annie believes Estelle is capable, yet worries Logan will panic if he finds out, and she doesn’t want Jeanie stressed on her wedding day.

She promises to look for Estelle quietly. As Annie is preparing to leave, Mac arrives to pick up a tie and cufflinks Logan had shipped to Annie’s place so Jeanie wouldn’t see them.

Annie is irritated it’s him, but when she tells him Estelle is missing, Mac insists on helping. He drives, and they start searching town without announcing what’s wrong.

They check the YMCA first, where Estelle often attends seniors’ classes. Mac distracts the front desk by pretending they want a membership so Annie can search unobtrusively.

Estelle isn’t there. Annie asks the older women to keep the situation quiet and to call if they see Nana.

Next they stop at the Pumpkin Spice Café, where Mac hears from Crystal that Dot mentioned meeting Estelle at the inn. At the inn, Annie and Mac search hallways.

When they nearly bump into Jeanie and her mother, Annie pulls Mac into a utility closet to hide. Standing close in the dark, Mac apologizes for leaving years ago and for hurting her.

Annie tries to brush it off, then finally admits she was devastated by his disappearance and won’t trust him again easily. She bolts from the closet, and Mac follows her outside, frustrated and hurt.

Annie says what they had mattered to her but refuses to reopen the past with the wedding hours away and Estelle still missing.

That night wedding decorating continues. Annie works with Kira and Daisy while Mac helps elsewhere in the barn.

Mac has adopted two kittens and carries them around, which Annie finds adorable even as she jokes that he’s using them to charm her. She names them Holly and Claus.

When Mac offers her a ride afterward, she agrees, and they stop at his house to settle the kittens. In the warmth of his kitchen, their guarded talk shifts into honesty.

Mac doesn’t push for promises; he shows care through patience and attention, and the old attraction returns, this time tangled with tenderness. Annie lets herself stay the night, exhausted, shaken, and wanting comfort she doesn’t want to admit.

A final clue sends them out of state to a snowy cul-de-sac in New Hampshire. Estelle and Dot are safe at the home of Estelle’s cousin Sylvia, with whom Estelle has feuded for years.

The “secret errand” was Estelle demanding a family heirloom for Logan’s wedding night. Sylvia resists until Mac calmly persuades her to hand it over.

The heirloom turns out to be a high-neck antique nightgown, more funny than romantic, and the absurdity makes everyone laugh as they rush back to Dream Harbor.

They arrive just in time for the ceremony. Under white Christmas lights, Jeanie and Logan exchange tender, sure vows, and the barn erupts with joy.

Annie gives a toast celebrating her lifelong friendship with Logan and her happiness to welcome Jeanie into that bond. At the reception, Annie sees Mac dancing with her sister Charlotte and feels jealous despite herself.

She drags Elliot, the new architect, onto the dance floor to needle Mac. Charlotte later tells Mac that Annie’s old hurt ran deep and that she needs proof he won’t leave again.

Mac cuts in on Annie’s dance and asks what she truly wants now. Annie finally says she wants him.

They slip outside, kiss by his car, and go home together. Mac confesses he never stopped loving her, that his leaving at nineteen came from fear and shame, and that seeing her again brought him back to Dream Harbor because he wanted another chance.

Annie admits she loves him too, and they choose to be together openly. Over the next week, they fall into a real relationship—messy, warm, and hopeful—ending the season not with a perfect erase of the past, but with a shared decision to stay and build something lasting.

Characters

Annie Andrews

Annie Andrews stands at the emotional and thematic center of The Gingerbread Bakery as someone who appears openhearted and easygoing to the town, yet privately carries scar tissue that shapes her instincts. She is a community anchor in Dream Harbor: devoted to her bakery, loyal to traditions, and deeply protective of the people she loves.

That protectiveness explains both her warmth and her volatility—her public objection to Mac at the wedding brunch shows how quickly she will leap to defend Logan when old wounds are touched. Annie’s identity is tightly woven with purpose and place.

She is ambitious in a grounded way, building a business through classes and persistence rather than through fantasy, and her pride in that work gives her a steady backbone. At the same time, her fear of failure and her reluctance to look foolish make her emotionally cautious; she would rather perform indifference than risk being seen as vulnerable.

Her relationship with Mac exposes that tension. Annie wants dependability and honesty, but she also wants to believe that people can grow, and her arc is learning to let present reality outweigh past hurt.

The push-and-pull between her longing and her distrust is not a sign of indecision so much as a sign of someone trying to protect a hard-won life while still leaving space for love.

Macaulay “Mac” Sullivan

Mac Sullivan begins as the town’s apparent troublemaker in Annie’s eyes and gradually becomes a portrait of regret, tenderness, and delayed self-understanding. As a teenager he bullied Logan, and that cruelty stains his reputation with Annie, but the adult Mac is defined less by arrogance than by shame and a desire to make things right.

He is charismatic in a low-key, practical way—able to talk his way through the YMCA desk, charm Sylvia into yielding the heirloom, and soothe tense social moments—yet beneath that ease sits a restless self-doubt. At nineteen he is directionless and frightened of being trapped in Dream Harbor, and the cross-country plan is as much flight from disappointment as it is a search for meaning.

His feelings for Annie arrive early and stay lodged deep; even after leaving, he never truly detaches, which makes his return less a surprise twist than the completion of an unfinished emotional sentence. Mac’s biggest flaw is avoidance—he runs when shame spikes or when the stakes feel too high—and his growth comes from choosing to stay, speak plainly, and be accountable.

In love, he is gentle, teasing, and openly adoring, but he also has to learn that desire isn’t enough unless it comes with reliability, the very thing Annie needs to heal.

Jeanie

Jeanie functions as both Annie’s beloved best friend and a quiet mirror for what secure love looks like. She is emotionally attuned, quick to worry about the health of the group, and invested in harmony, which is why Annie’s outburst at the brunch hits her so hard.

Jeanie is not fragile, though; she responds to tension with a desire to repair rather than to retreat, and her wedding weekend shows her ability to hold joy even when the people around her wobble. In her partnership with Logan she embodies steady affection and humor, making promises that are sincere without being solemn.

She also represents the social heart of Dream Harbor’s found-family culture—someone who can pull people into celebration and make them feel taken care of. Her role in the story is subtle but essential: she anchors the weekend so Annie and Mac’s unresolved past has a pressing, real-world backdrop, not just a private drama.

Logan

Logan is the emotional hinge of Annie’s loyalty and of Mac’s guilt. As a child grieving his mother, he was vulnerable to Mac’s teasing, and the wound from that period echoes into adulthood through Annie’s fierce protection and Mac’s remorse.

Adult Logan is gentle, slightly anxious, and deeply loved by his friends, with a shy self-consciousness about public speaking that makes him feel human and relatable. He also has a quiet resilience; he accepts Mac’s apology even when confused, suggesting a capacity to move forward without bitterness.

Logan’s devotion to Jeanie is wholehearted and tender, and his vows reveal someone who loves with humility and gratitude. The missing-Estelle crisis underscores how much his stability depends on family bonds, especially his Nana, which makes the wedding’s success feel like a triumph of community care.

Hazel

Hazel is Annie’s long-time friend and emotional spark plug in the group. She is blunt, excitable, and protective in her own right, and she often functions as the one who says what others are tiptoeing around.

Her panic over Estelle’s disappearance shows her sense of responsibility to Logan and Jeanie, while her past interruption at the diner illustrates how her intense loyalty to Annie can unintentionally create pressure or misunderstandings. Hazel is also a social orchestrator; she notices Annie’s spirals quickly and tries to steer her back toward perspective.

She carries the town’s gossip-and-care energy in a loving way, nudging people toward truth even when they resist it. In the overall dynamic, Hazel is the friend who keeps the emotional temperature high enough that hidden feelings can’t stay hidden forever.

Kira

Kira is competence wrapped in warmth, an efficient planner who also understands the emotional undercurrents of the people she’s helping. Running the rehearsal at her family’s Christmas tree farm, she is practical and calming, which makes her a stabilizing presence for the wedding weekend.

She sees Annie’s distraction and Mac’s interest without judgment, and her gentle teasing is really a form of pushing Annie toward honesty. Kira also embodies Dream Harbor’s spirit of communal celebration; the barn she renovates and decorates becomes a literal stage for love, reconciliation, and the town’s traditions.

Her role is not just logistical but symbolic: she provides the safe, twinkle-lit space where truth has a chance to surface.

Noah

Noah operates as a light, steady counterbalance in the male friend group. He teases Logan to ease tension and fits naturally into the wedding party dynamic, suggesting long familiarity and comfort.

Paired with Hazel, he adds to the weekend’s atmosphere of settled affection, which in turn highlights Annie’s loneliness and unresolved yearning. Noah isn’t deeply explored in the summary, but what does come through is his easy camaraderie and his role in making the social world feel lived-in and supportive.

Bennett

Bennett contributes to the sense of an interconnected, affectionate community. He’s present in rehearsals and decorating, working alongside Mac and moving comfortably in the circle, which helps show that Mac is not an outsider to everyone—only to Annie’s heart.

Bennett’s relationship with Kira adds to the backdrop of happy couples that heightens Annie’s emotional vulnerability. He is part of the story’s chorus of friends who normalize love and partnership as something achievable, not rare.

Iris

Iris is a quietly capable presence who moves between roles with ease—running a senior aerobics class, helping keep town matters discreet, and sharing in the wedding’s social warmth. She carries a calm maturity that makes Annie comfortable enough to confide in her, and her inclusion in the older women’s circle at the YMCA also highlights the layered community Dream Harbor has across generations.

Iris’s relationship with Archer adds another example of a loving bond that feels stable and adult, reinforcing the story’s theme that real love is built through everyday care.

Archer

Archer is Dream Harbor generosity personified. Providing the rehearsal dinner meal and moving through the weekend with warmth, he represents the way this town shows love through acts of service.

His easy rapport with Annie suggests he is one of the people who fully sees her strengths and soft spots. Archer’s partnership with Iris reinforces his steadiness; they are part of the social fabric that holds the younger characters when emotions flare.

Daisy

Daisy brings vulnerability and hope to the friend group through her conversation about the “curse” surrounding her flower shop. She is talented, hardworking, and quietly discouraged by the pattern of weddings turning into funerals in her orbit.

Her confession lets the story acknowledge fear without letting it dominate; Annie’s reassurance helps Daisy reclaim pride in her craft. Daisy also functions as another mirror for Annie’s own fear of failure—someone who keeps showing up for her work even when the outcome feels ominous.

She adds a layer of tender realism beneath the romance.

Estelle

Estelle, Logan’s Nana, is both comic engine and emotional keystone. Her “disappearance” propels the plot, but it’s driven by love rather than danger; she is mischievous, fiercely determined, and convinced that tradition matters enough to break rules for it.

The old feud with Sylvia shows her stubbornness and long memory, yet her eventual laughter in the car reveals a playful self-awareness. Estelle’s deep bond with Logan makes her important beyond humor; she represents the family continuity he clings to, and her presence at the wedding underscores that love is not only romantic but also generational.

She is the kind of elder who refuses to fade quietly into the background, and the town seems better for her noise.

Dot

Dot is Dream Harbor’s nurturing heartbeat, an older figure who offers comfort through food, gossip, and quiet guidance. In the past she sells hot chocolate at the market; in the present she’s spirited enough to join Estelle on a secret mission.

Dot’s role in sheltering Estelle and then apologizing afterward shows a balance of kindness and accountability. She also acts like an affectionate aunt to Annie, teasing her gently about Mac and noticing the emotional truths younger people are trying to hide.

Dot’s warmth makes the town feel safe, and her presence ties the holiday atmosphere to an enduring sense of home.

Charlotte

Charlotte, Annie’s sister, is used sparingly but powerfully as someone who sees Annie’s pain clearly and refuses to minimize it. Her slow dance with Mac triggers Annie’s jealousy, but more importantly, her conversation with Mac is a direct moral checkpoint: Annie was hurt deeply, and if Mac returns, he must return responsibly.

Charlotte functions as protective family honesty, ensuring the romance doesn’t skip over the cost of the past. She gives voice to the boundary Annie struggles to articulate for herself.

Elliot

Elliot, the architect at the inn, serves as a small but telling catalyst. Annie’s pointed flirtation with him is less about true interest and more about reclaiming power and poking at Mac’s insecurities.

Elliot’s presence reveals Annie’s defensive strategy: when she feels exposed, she tries to reframe herself as unattached and in control. As a character, he represents a possible “safe” alternative future, but the story uses him to show that Annie’s feelings for Mac are not replaceable with convenience.

Sylvia

Sylvia, Estelle’s cousin, enters as an obstacle shaped by an old family feud. She is tiny, sharp-edged, and proud of her branch of the family, resisting Estelle’s bulldozing with equal stubbornness.

Yet her hospitality—taking in Estelle and Dot despite the fight—shows an underlying decency. Sylvia’s eventual surrender of the heirloom after Mac charms her suggests she is not cruel, just entrenched, someone who needs respect before she yields.

She adds texture to Estelle’s backstory and illustrates how love and rivalry can coexist in family ties.

Mayor Kelly

Mayor Kelly appears as an officiant, but that role matters: she embodies the town itself blessing Jeanie and Logan’s union. Her presence reinforces Dream Harbor as a close-knit place where civic and personal life overlap warmly.

By officiating with humor and affection, she helps keep the wedding rooted in community rather than spectacle.

Jack

Jack is a minor but functional character who represents the inn’s quiet competence and the town’s network of information. By confirming Estelle’s possible presence and offering context without drama, he helps keep the search moving.

He is part of the subtle infrastructure of Dream Harbor, where people notice each other and try to help.

Crystal

Crystal, the barista at the Pumpkin Spice Café, acts as a discreet messenger. She shares Dot’s lead quietly and trusts Mac with the information, showing the town’s collective instinct to protect the wedding weekend while still solving problems.

Even briefly, Crystal illustrates how Dream Harbor runs on soft cooperation and shared care.

Henry

Henry is a tiny thread in the mystery of Estelle’s disappearance, but his mention conveys something about the household dynamic around Logan’s family: Estelle is not monitored like a fragile elder; she has agency that others respect. Henry’s casual note that she left early for an errand fits the theme that older characters in this story maintain lively independence.

Tina

Tina at the YMCA is a comedic foil and a demonstration of Mac’s social skill. His charm with her allows Annie to search without panic spreading, and the fact that he ends up stuck with paperwork adds a light consequence to his flirtatious improvisation.

Tina’s role highlights the way Mac uses humor and smoothness not to manipulate, but to solve things gently.

Themes

Community as a Living Support System

From the first gathering at the pancake house to the Christmas market, the town of Dream Harbor operates like a breathing social organism in The Gingerbread Bakery. Annie’s identity is inseparable from the people around her: her friendships, her role as a baker, and her place in the rituals that bind the town together.

The wedding weekend underscores how deeply communal life shapes individual choices. Annie’s outburst against Mac doesn’t just create awkwardness between two people; it threatens the emotional weather of the entire celebration.

Her panic afterward isn’t only embarrassment, but the fear of cracking something sacred in her small world. That sense of collective responsibility is everywhere.

People keep quiet about Estelle’s disappearance not because they are secretive by nature, but because they understand how fragile joy can be when a town event is on the line. Even the search itself becomes a communal act, relying on informal networks, shared knowledge of habits, and trust in one another’s discretion.

The same community that magnifies conflict also offers a path toward healing. Mac is not treated as an outsider even when Annie is hostile to him; he’s still part of the wedding party, still teased, still included in the town’s rhythms.

That welcome creates conditions where reconciliation is possible. Meanwhile, Annie’s bakery dream is shown as something that grows from communal soil.

Her early cookie stall is a public beginning, and her long-term business ambition assumes a town that will show up, buy, and care. The final scenes of friends greeting Annie and Mac as a couple, already expecting the outcome, reveal the town’s quiet role as matchmaker and witness.

Love and belonging here are not private achievements; they are validated and sustained by a shared social world that holds history, forgives missteps, and celebrates returns.

Forgiveness and Second Chances Without Erasing the Past

Annie’s hatred of Mac is rooted in memory, and the book refuses to treat memory as something flimsy or melodramatic. Her outrage comes from loyalty to Logan and from her own unspoken hurt, and that makes forgiveness a moral act rather than a convenient plot turn in The Gingerbread Bakery.

When Mac apologizes for his childhood cruelty, the apology matters because it recognizes a real wound that shaped Annie’s view of him for years. His willingness to text Logan immediately, without defending himself, shows a shift from immature self-absorption toward accountability.

The point isn’t that what he did was small; it’s that he finally sees its weight.

What makes the forgiveness theme richer is how it extends beyond simple “sorry-and-done. ” Annie can forgive the boy who taunted Logan while still struggling to trust the man who vanished from her life after their teenage closeness.

The book draws a clear line between forgiving someone’s past wrongs and rebuilding safety in the present. Annie’s sharpness in the closet scene—her anger, humiliation, and refusal to be softened by Mac’s charm—comes from the reality that some hurts linger because they were never acknowledged properly.

Mac’s shock at her confession isn’t framed as her cruelty but as the cost of his earlier cowardice.

Second chances also appear as choices that must be earned. Mac doesn’t get Annie back merely by returning to town or flirting well.

He has to show consistency: helping search for Estelle, standing between feuding relatives, and staying present when Annie is messy and defensive. Annie, too, must accept that granting another chance doesn’t mean pretending the first failure didn’t happen.

Their reunion works because both hold the full truth: love existed, pain existed, and both are allowed to matter. The ending feels satisfying not because the past disappears, but because it is finally faced and integrated into a new beginning.

Fear of Being Stuck Versus Fear of Failing

Two contrasting anxieties drive the emotional engine of The Gingerbread Bakery: Mac’s fear of stagnation and Annie’s fear of falling short. At nineteen, Mac feels trapped by expectation and by his own uncertainty.

Working at his father’s pub and living at home make him ashamed, not because the work is inherently bad, but because it doesn’t match the person he imagines he should become. His planned road trip represents a search for identity, a belief that leaving is the only way to grow.

Annie’s mindset is different but equally pressured. She stays, builds, studies, and sells cookies in public because her dream has a concrete shape.

Yet that clarity comes with risk. Her biggest fear is failure, and the bakery goal is not merely career ambition—it is the measure of whether she was right to believe in herself.

The relationship between them becomes a collision of these fears. Annie is attracted to Mac but resents his restlessness, because it threatens the stability she counts on.

Mac is drawn to Annie’s certainty but feels unworthy of it, because her groundedness highlights how lost he feels. Their early closeness is shadowed by his departure, and that departure is shown not as malice but as a fear response.

When Annie later calls out how he disappeared, she is voicing a deeper dread: that trusting someone who doesn’t know where he belongs will pull her into chaos or rejection.

What’s interesting is that both fears evolve. Mac learns that leaving didn’t fix him; it only delayed the reckoning.

His confession that he stayed nearby out of shame reveals that running can be another kind of self-imprisonment. Annie, meanwhile, learns that her intensity and control sometimes protect her from vulnerability more than from failure.

Accepting Mac’s return requires her to tolerate uncertainty, to risk emotional failure the way she risks professional failure every day. By pairing these two forms of fear, the book suggests that growth isn’t choosing stay or go, but learning to move through fear without letting it define every decision.

Emotional Vulnerability Behind Humor and Conflict

A lot of what Annie and Mac say to each other is funny, prickly, or flirtatious, but the humor is never just decoration in The Gingerbread Bakery. It’s a shield and a bridge at the same time.

Annie’s sarcasm and Mac’s teasing cover nerves that neither wants to expose directly. Their banter about cookies, dealbreakers, or kitten names looks light on the surface, yet each joke is a test: “Can I be close to you without getting hurt?

” Annie’s habit of assuming the worst in Mac is another defense mechanism. Anger gives her control.

If she stays mad, she doesn’t have to risk being soft.

Mac’s vulnerability is similarly masked. His charm often functions as a way to stay wanted without proving he deserves to be.

When he kneels on the kitchen floor to please Annie, it’s not only erotic; it’s a statement of care and repentance that he can’t quite express in plain language yet. The closeness in hidden spaces—the utility closet, the truck, the kitchen at night—shows how safety for them begins in moments where they can’t perform for an audience.

Annie’s outburst about their past intimacy, while harsh, is also a raw admission that she felt pressured to pretend competence and satisfaction as a teenager. Her honesty there is a painful kind of courage, claiming her right to truth even when it makes her look imperfect.

The book doesn’t romanticize vulnerability as pretty. It arrives tangled with jealousy, misunderstandings, and fear.

Annie provoking Mac by dancing with Elliot isn’t noble behavior, but it reveals how deeply she cares, and how scared she is of caring. Mac’s anger in the parking lot demonstrates that he wants to be taken seriously, not just tolerated.

Each conflict peels away another layer of protective performance. By the time they admit love, it lands not as a sudden emotional peak but as the result of slowly learning that they can survive honesty with each other.

The theme argues that real intimacy isn’t the absence of mess; it’s choosing closeness even when the mess shows.

Commitment as an Act of Presence and Timing

Love in The Gingerbread Bakery is shaped by timing, not in a whimsical “right person, wrong time” way, but in a practical and emotional sense. At nineteen, Annie and Mac connect in a brief, glowing season of possibility.

Yet the looming deadline of Mac’s departure makes their relationship feel like something that might be beautiful but temporary. Annie tries to seize time by proposing sex bluntly, as if intensity could outpace inevitability.

Mac, on the other hand, experiences the same deadline as a reason to retreat. Their youthful version of love is real, but it lacks the maturity to handle what’s at stake.

In the present, timing becomes a test of whether commitment can be different this time. The wedding weekend compresses emotions into a short span, forcing Annie and Mac to confront unresolved history while surrounded by symbols of lifelong partnership.

Estelle’s disappearance adds urgency that is emotional as much as logistical. When they search together, they are practicing a kind of partnership: coordinating, relying on one another’s strengths, and making room for each other’s instincts even while arguing.

Mac’s decision to return to Dream Harbor is not treated as fate; it’s a choice to stop circling the edges of his life. Annie’s decision to want him openly is also a choice, a refusal to let fear dictate her future.

The final commitment doesn’t erase the fact that time once broke them. Instead, it shows that timing can be revised through presence.

Mac proves he is no longer leaving at the first sign of shame. Annie proves she no longer wants love only on her terms.

Their week of secrecy after the wedding is almost like a quiet rehearsal for a shared life—testing that desire can coexist with daily reality. The postcard Annie gives him on Christmas morning captures the theme neatly: his journey matters because it ends in return, and return matters because it turns longing into a life lived side by side.

Commitment here is not a grand declaration; it is staying, showing up, and letting the relationship take up full, honest time.