The Good Vampire’s Guide to Blood and Boyfriends Summary, Characters and Themes

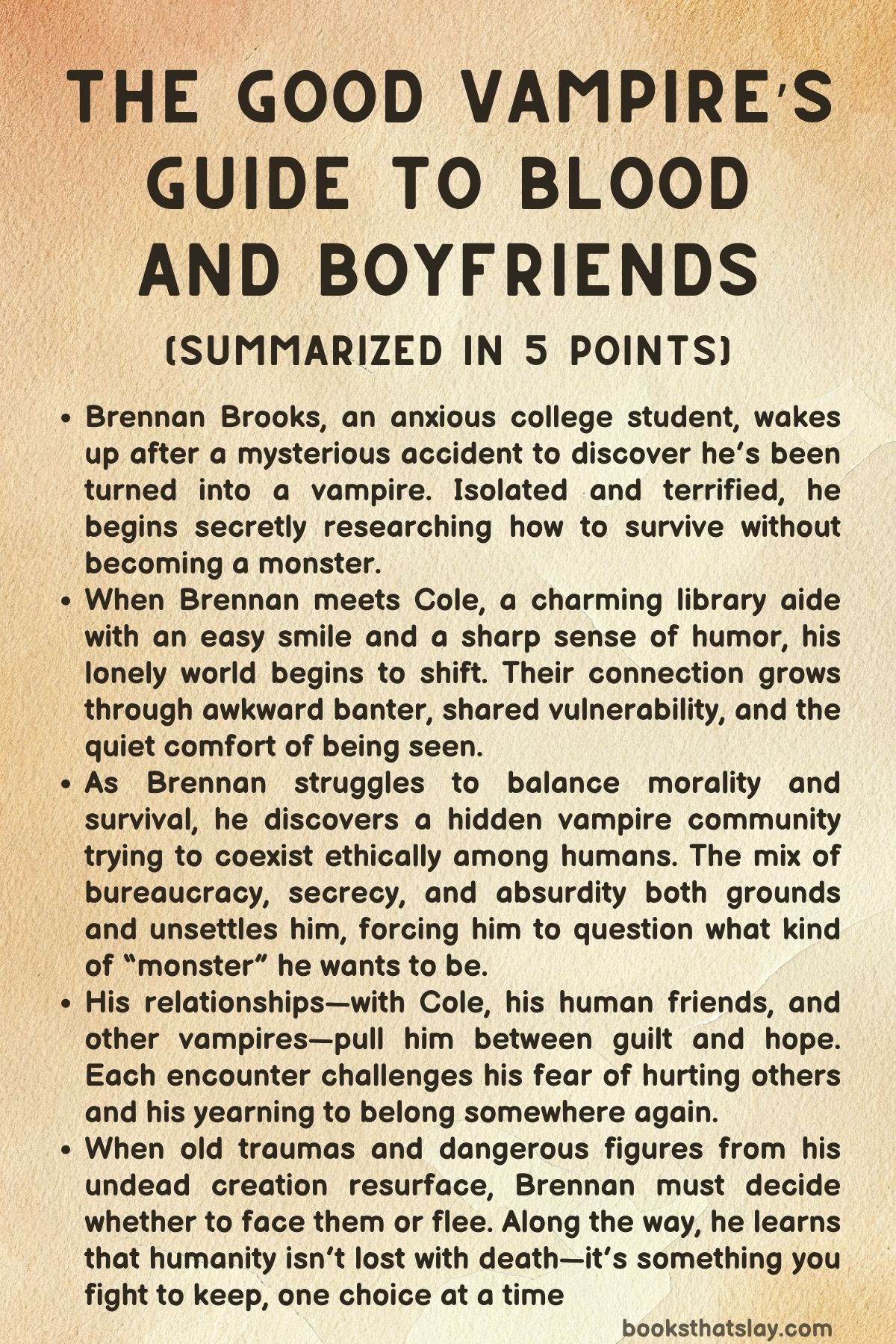

The Good Vampire’s Guide to Blood and Boyfriends by Jamie D’Amato is a witty and emotionally charged take on vampire fiction that mixes humor, introspection, and romance with a touch of supernatural chaos. It follows Brennan Brooks, a college student who wakes up to find himself a vampire, burdened with guilt, anxiety, and the daunting task of figuring out how to live ethically as a creature of the night.

Through friendship, love, and existential reflection, Brennan learns that being undead doesn’t stop life from being messy, hilarious, and meaningful. The novel explores morality, mental health, and identity, blending sharp dialogue with moments of deep sincerity.

Summary

Brennan Brooks, a college student at Sturbridge University, finds his world turned upside down after waking up from an accident only to realize he has become a vampire. Confused and terrified, he throws himself into frantic research at the campus library, desperate to make sense of his new reality.

His hunger is unbearable, his senses are unnervingly sharp, and his moral compass is in turmoil. In the midst of this, he meets Cole, a kind and charming library aide whose warmth and humor begin to ground Brennan amid the chaos.

Cole’s easy kindness stands in stark contrast to Brennan’s self-loathing and guilt—especially when Brennan suspects he might have killed someone the night he was turned.

As the days pass, Brennan survives on animal blood, burying his victims in shame. When he discovers traces of his own death at the accident site, the truth of his transformation becomes undeniable.

He begins questioning his humanity and morality, even as he tries to maintain a semblance of normal life, hiding his secret from his overworked mother. Determined to survive without killing, Brennan plans to steal blood from the university’s medical building.

His attempt backfires when Cole catches him mid-theft, fangs bared. To Brennan’s surprise, Cole doesn’t run—he listens, asks questions, and even jokes about it.

Their bond begins here, fragile but real.

Just as Brennan begins to feel a tentative sense of control, he receives a mysterious text: “We know about you. ” Despite his fear, he keeps up appearances, joining his friends for their weekly “Bachelorette Night,” where Cole is also present.

The evening’s playful games turn unexpectedly serious, forcing Brennan to confront his loneliness and past trauma. When panic overwhelms him, Cole follows him outside, leading to an honest conversation about vulnerability, kindness, and belief in things beyond the ordinary.

The night ends with mutual trust, a spark of connection, and Brennan finding Twilight left at his door—Cole’s teasing way of showing support.

Days later, another text arrives, directing Brennan to meet someone named Sunny. Against Cole’s warnings, he travels to Boston, where he discovers a vampire orientation meeting led by Sunny, Nellie, and Dominique—Dom—the driver who accidentally killed him.

Brennan learns that vampires have organized clans with moral codes; the local “urban” clan feeds on donated blood, while others are far darker. Horrified by this bureaucratic underworld, Brennan tries to hold on to his ethics.

Nellie gives him guidance, resources, and a support network. For the first time, Brennan feels he might belong somewhere.

Back on campus, Brennan’s connection with Cole deepens through shared jokes, late-night talks, and an easy emotional intimacy neither expected. Cole’s empathy helps Brennan see his condition less as a curse and more as something to navigate.

But beneath the surface, danger brews. Brennan learns that Travis—the vampire who turned him—is ancient, reckless, and unpredictable.

When Brennan and Dom track him down, Travis reveals he turned them both to save their lives after the crash. His carefree attitude disgusts Brennan, who discovers the truth about Dom’s sister Evelyn: in her bloodlust, Dom accidentally killed her.

Brennan’s death, Dom’s guilt, and Travis’s carelessness are all intertwined in tragedy. Brennan leaves furious, seeing how immortality only magnifies human flaws.

Despite everything, Brennan finds solace in Cole. Their relationship grows from awkward friendship into something tender and romantic.

They share vulnerabilities and joy, finding humor amid fear. When they finally kiss, the moment is intense—Brennan’s vampiric instincts nearly overpower him.

Cole’s calm trust steadies him. But their fragile peace shatters when Mari, Brennan’s roommate, discovers his stash of stolen blood and accuses him of being dangerous.

Cole defends him, but Mari’s fear and anger dredge up Cole’s painful past. The confrontation leaves Brennan alone and broken.

Soon after, Dom reappears, spiraling into resentment and violence, determined to seize power.

News spreads of mysterious student deaths, and Brennan realizes Dom has lost control. Ignoring Nellie and Sunny’s warnings, he tries to stop her.

When he finds Dom gone, she leaves behind a flyer for a grand “Vampire Ball,” signaling her next move. Brennan decides to protect Cole and his friends, even carving protective sigils around Mari’s home.

Time passes; he and Cole reconcile after a heartfelt reunion, admitting how much they missed each other. Their love deepens through music, laughter, and shared honesty.

But the calm doesn’t last. Travis resurfaces, hinting that Dom plans to recreate a century-old vampire rebellion started by his former lover Shea.

Brennan realizes that history may repeat itself at the upcoming Vampire Ball. He teams up with Cole, Mari, Tony, and even Dom—forming an unlikely alliance to stop the chaos.

Brennan and Cole make peace with their fears, deciding to face danger together. Their affection becomes both anchor and motivation.

The night of the ball arrives. The hotel shimmers with elegance, but beneath the glamor lies menace.

Travis’s psychic powers trigger a frenzy among vampires, turning the event into chaos. Humans panic as bloodlust spreads.

Brennan and his friends launch their makeshift defense: Tony wields a garlic-filled water gun, Mari manages the panicked crowd, and Cole fights beside Brennan. Amid the violence, Brennan tries to reach Travis through reason, reminding him of love lost and the choice to change.

For a moment, it works—but Dom strikes the final blow, killing Travis and ending his centuries of chaos. She weeps, not triumphant but broken.

Sunny and Nellie swiftly take control, erasing memories and restoring order. They spare Dom’s life, sending her abroad for redemption.

As calm returns, Brennan and Cole reaffirm their love, promising to face immortality hand in hand. Two weeks later, life feels almost normal again—classes, movie nights, and laughter with friends.

A letter from Dom arrives from Ireland, describing her journey toward peace and self-forgiveness. Brennan reads it in Cole’s arms, finally understanding that immortality isn’t about escaping life’s pain—it’s about finding reasons to keep living through it.

The Good Vampires Guide to Blood and Boyfriends ends on a note of quiet hope.

Characters

Brennan Brooks

Brennan Brooks stands at the heart of The Good Vampire’s Guide to Blood and Boyfriends, a deeply conflicted protagonist navigating the moral, psychological, and emotional consequences of sudden transformation. His journey from human student to newly turned vampire is an exploration of identity, guilt, and moral endurance.

From the outset, Brennan is defined by his introspection and self-loathing; his vampirism magnifies the depression and trauma he already carried from his previous suicide attempt. The vampire’s thirst becomes an allegory for mental illness—an unwanted, consuming part of himself he tries desperately to control.

His initial horror at his condition and obsessive moral reasoning show a mind that intellectualizes pain to survive it. Yet, beneath his overthinking, Brennan has a profoundly empathetic heart; his greatest fear isn’t dying or losing his humanity—it’s harming others.

His relationship with Cole becomes a lifeline, reintroducing warmth and vulnerability into a life dominated by secrecy and self-punishment. Through Cole’s gentle steadiness, Brennan learns that acceptance doesn’t mean surrendering to darkness but finding equilibrium within it.

Over the story, his transformation is both physical and philosophical: from guilt-ridden recluse to a self-aware, morally grounded vampire who can see immortality not as damnation but as a chance for love and growth. Brennan’s arc closes on a note of hard-earned peace—his immortality becomes not a curse but a horizon.

Cole

Cole functions as Brennan’s emotional counterbalance and moral anchor throughout The Good Vampire’s Guide to Blood and Boyfriends. Initially introduced as the campus’s comforting “Blanket Guy,” Cole embodies warmth, humor, and resilience—traits that contrast Brennan’s haunted introspection.

Yet beneath his lighthearted demeanor lies depth; Cole, too, struggles with depression and trauma, particularly connected to someone named Noah from his past. His capacity to empathize, even in the face of Brennan’s monstrous nature, reveals a remarkable strength of character.

Cole’s relationship with Brennan unfolds with emotional authenticity, rooted in shared vulnerability rather than supernatural allure. His curiosity about the supernatural is genuine, stemming from a longing to believe in mystery amid the mundane pains of life.

That curiosity becomes a symbol of hope—the idea that wonder can coexist with sorrow. Even when faced with danger, as in his confrontations with Brennan’s vampiric instincts or the threats of Travis and Dom, Cole responds not with fear but understanding.

By the story’s end, he emerges not as a mere love interest but as a stabilizing force—someone who sees Brennan entirely and still chooses him. His compassion is radical, his love a quiet rebellion against despair.

Dominique (Dom)

Dominique is perhaps the novel’s most tragic and volatile figure. The driver responsible for Brennan’s death and her own transformation, Dom embodies guilt and grief personified.

Her existence is haunted by the death of her sister, Evelyn, whose loss defines every aspect of her character. Dom’s relationship with vampirism is one of self-destruction and defiance; she oscillates between wanting power and wanting oblivion.

Her bitterness toward her creator, Travis, and her inability to forgive herself for Evelyn’s death drive her toward recklessness and violence. Yet beneath her aggression lies a deep yearning for control—a desperate need to reclaim agency after trauma.

Dom’s evolution from antagonist to reluctant ally marks a powerful redemption arc. Her decision to help Brennan at the end, and her final exile to Ireland in search of meaning, underscore her fragile but real desire to heal.

Dom’s tragedy is that she understands monstrosity too well—she sees it as both punishment and protection. In the end, she becomes a mirror for Brennan: both are shaped by guilt and survival, but where Brennan finds peace through love, Dom seeks it through solitude.

Nellie

Nellie represents the bureaucratic and therapeutic heart of the vampire community in The Good Vampire’s Guide to Blood and Boyfriends. Cheerful, practical, and endlessly organized, she is a model of vampiric restraint and structure.

Her creation of vampire orientations and pamphlets transforms horror into administration, humorously grounding the supernatural in the mundane. Yet her optimism and professionalism conceal centuries of experience and quiet strength.

She bridges the gap between morality and necessity, guiding Brennan toward understanding ethical vampirism without judgment.

What makes Nellie fascinating is her dual nature: both nurturing and commanding.

She recognizes the need for structure in immortal life, understanding that ethics and order are the only ways to keep chaos at bay. Her mentorship of Brennan mirrors that of a patient teacher guiding a frightened student through trauma.

Even in moments of crisis, Nellie’s steady demeanor grounds the others, showing that immortality does not have to erode one’s humanity—it can refine it.

Sunny

Sunny, Nellie’s counterpart and co-leader, represents the modern, digital face of vampirism—sarcastic, tech-savvy, and steeped in irony. At over three hundred years old, she merges centuries of experience with the sensibilities of an influencer, embodying how immortality adapts to the times.

Sunny’s intelligence and control contrast sharply with Travis’s chaos; where he seeks freedom, she seeks order through narrative manipulation. Her ability to glamour crowds and reshape perception is both literal and symbolic—she manages not just humans’ memories but the public story of vampires.

Her role in the narrative, though secondary, is pivotal: she ensures the vampire world’s survival through image and discipline. Sunny understands that secrecy and stability depend on managing appearances, making her the pragmatic architect of peace.

Yet, beneath the irony, she carries the weight of leadership—a constant balancing act between protecting her kind and preserving morality.

Travis

Travis serves as the story’s chaotic catalyst—a relic of the old, lawless vampiric world. His personality is disarming at first glance: a weed-smoking, joke-cracking immortal who treats eternity like an endless college party.

Yet his indifference hides something darker: the nihilism of someone who’s lived too long without purpose. As Brennan’s inadvertent sire, Travis becomes both mentor and cautionary tale.

His irresponsibility leads to tragedy—the deaths of Evelyn and Brennan’s transformation—and his refusal to reckon with it makes him the embodiment of moral decay.

However, Travis is not purely evil.

His final confrontation reveals a flicker of conscience and exhaustion. When Brennan appeals to his lost love Shea, the human remnants within him briefly resurface.

His death is both tragic and redemptive, symbolizing the end of an old order of vampirism defined by chaos, secrecy, and violence. Through Travis, the book interrogates the danger of apathy—how immortality without empathy curdles into monstrosity.

Marisela (Mari)

Mari is Brennan’s loyal, fiery roommate, whose pragmatic skepticism often grounds the supernatural chaos around her. Initially dismissive of Brennan’s condition, she quickly becomes one of his fiercest protectors once she learns the truth.

Her compassion is expressed through action rather than sentiment—arming herself with garlic and helping orchestrate a covert blood drive to prevent mass tragedy. Mari’s moral compass is sharp, and her anger at betrayal or harm is rooted in care.

Her dynamic with Brennan evolves from roommate banter to deep camaraderie. She is also a voice of human resilience within a supernatural narrative—proof that courage and morality are not limited to the immortal.

Mari’s later relationship with Tony softens her edges without diminishing her strength, positioning her as one of the most humanly authentic characters in the story.

Tony

Tony provides warmth, humor, and balance within Brennan’s found family. Initially a background presence—the fun roommate hosting “Bachelorette Night”—he gradually becomes a vital part of the story’s emotional infrastructure.

His easygoing personality hides surprising loyalty and bravery, especially during the climactic battle where he arms himself with garlic water to save others. Tony represents acceptance without judgment; he never treats Brennan as less than human.

His bond with Mari and steady friendship with Brennan anchor the narrative in the comforts of normalcy amid chaos.

Themes

Identity and Self-Acceptance

Brennan’s journey throughout The Good Vampire’s Guide to Blood and Boyfriends centers profoundly on the question of identity—who he is, who he was, and who he is allowed to become. His transformation into a vampire destabilizes every aspect of his sense of self, amplifying struggles he already faced as a young adult navigating mental illness and isolation.

Before turning, Brennan was already fragile, marked by a suicide attempt and a deep sense of alienation from others. Becoming a vampire doesn’t erase his insecurities; rather, it makes them literal and physical.

His thirst for blood becomes an externalization of the hunger for belonging and purpose that had defined his human life. The novel uses vampirism as both a metaphor and a mirror, forcing Brennan to confront the parts of himself he despised.

Every moral choice he makes—whether feeding on animals, stealing blood, or confessing to his crimes—is a step toward accepting not only what he is but also what he feels. The process of reconciling humanity with monstrosity parallels the experience of living with mental illness or queerness in a judgmental world: learning to exist authentically without apology or shame.

By the novel’s end, Brennan’s identity evolves into something whole rather than split between human and vampire. He doesn’t cure his vampirism or reject it; he integrates it, acknowledging that the darkness within him is neither wholly evil nor incompatible with love, community, and compassion.

His self-acceptance marks a triumph of coexistence—the recognition that identity is not something to purge but something to understand and embrace.

Morality and Ethical Survival

The novel examines morality not through abstract philosophy but through visceral survival. Brennan’s first moral crisis arises when he realizes he might have killed someone the night he was turned.

His panic and shame drive him into obsessive ethical reasoning—debating utilitarianism, Kantian duty, and the value of his own life. Yet the story consistently reminds him that moral frameworks falter under the weight of hunger, trauma, and loneliness.

The “urban vampires,” led by Nellie and Sunny, represent an attempt at institutional ethics—feeding from blood drives and enforcing laws to prevent human deaths. But even that system is bureaucratic and fragile, exposing how morality can become regulation rather than empathy.

Brennan’s choice to steal blood, his arguments with Dom about killing, and his confrontation with Travis all test the boundaries between moral idealism and moral necessity. What makes the novel compelling is its refusal to romanticize moral purity.

Brennan is not a saint resisting temptation; he is a boy learning that survival often means compromise. His guilt never disappears, but it transforms into responsibility—an awareness of how his actions ripple through others.

In the climactic ball scene, his decision to confront Travis not with violence but with emotional truth underscores a matured moral understanding: that compassion can be a form of resistance. The book ultimately suggests that ethical living is not about following absolute rules but about choosing empathy over apathy, even when the world (or eternity) tempts you otherwise.

Love, Trust, and Vulnerability

At its emotional core, the relationship between Brennan and Cole explores how love can coexist with fear and imperfection. Their bond develops through awkward humor, shared trauma, and mutual recognition of brokenness.

Cole’s gentle curiosity contrasts Brennan’s guardedness; he doesn’t run from Brennan’s monstrosity but meets it with empathy. Their growing intimacy tests both characters’ capacity for trust—especially when vampirism turns vulnerability into literal danger.

Every touch and kiss becomes a test of restraint, every confession a step into potential rejection. The scene where Cole touches Brennan’s fangs and says he trusts him distills the novel’s emotional thesis: love is not the absence of fear but the decision to stay despite it.

This dynamic extends beyond romance into friendship and chosen family. Characters like Mari and Tony, who begin skeptical or frightened, ultimately choose to stand by Brennan because they see his humanity.

Love, in this story, becomes an act of moral courage. It refuses to categorize people as monsters or victims.

The narrative also subverts the typical vampire romance trope by focusing not on seduction but on communication and consent. Brennan and Cole’s relationship grows through dialogue and honesty, emphasizing emotional intimacy over supernatural allure.

By the end, love is not a reward for redemption but the mechanism through which redemption becomes possible.

Trauma, Guilt, and Redemption

Trauma pervades every layer of The Good Vampire’s Guide to Blood and Boyfriends—personal, emotional, and even supernatural. Brennan’s suicide attempt before his transformation defines his relationship with existence; he begins the story believing his life has no worth, and becoming undead literalizes that detachment.

His guilt over possibly killing someone, over surviving when others died, and over losing control of his body and mind threads through his narrative voice. The novel treats guilt not as punishment but as a shadow that must be acknowledged and understood.

Dom’s story mirrors this theme: her accidental killing of her sister Evelyn becomes an unbearable wound that drives her toward self-destruction and later, reluctant heroism. Both Brennan and Dom embody survivors who carry the dual burden of grief and shame, and their arcs intertwine in a shared search for forgiveness.

Redemption in this novel is not divine or absolute—it is practical, quiet, and earned through connection. Brennan redeems himself not by erasing his sins but by choosing to act differently when given power.

In confronting Travis, he rejects the nihilism of ancient immortals who see morality as meaningless, proving that accountability is possible even for monsters. His redemption is inseparable from self-forgiveness; it culminates in his ability to love and be loved again.

The novel closes not with grand salvation but with small, hopeful continuity—a man who once sought death now planning eternity with the people who made him want to live.

Community and Belonging

The longing for belonging defines every character’s arc, from Brennan’s loneliness at the university to the dysfunctional hierarchy of vampire clans. The book reframes vampirism not as exile but as a new social identity—one that forces its members to build unconventional communities.

Nellie and Sunny’s “New England clan” serves as a metaphor for chosen families and marginalized collectives, using structure to survive in a world that fears them. However, the bureaucracy and politics within that community also reveal how belonging can slip into conformity or control.

Brennan’s ambivalence toward the clan reflects the difficulty of finding a place where one’s ethics and identity align. His eventual team—Cole, Mari, Tony, and Dom—embodies the possibility of authentic belonging built on acceptance rather than obligation.

Their “New Squad” symbolizes an inclusive community that thrives on mutual respect, not power. The story uses the vampire ball as a culmination of these social tensions, where unity and chaos coexist.

Even Travis’s defeat depends not on dominance but on collaboration—proof that collective care can overcome centuries of violence. By the end, community becomes the answer to both loneliness and moral paralysis.

Brennan’s immortality, once a curse, becomes bearable because he no longer faces it alone. His newfound belonging affirms one of the novel’s central truths: survival means little without connection, and eternity means nothing without love.