The Greatest Lie of All Summary, Characters and Themes

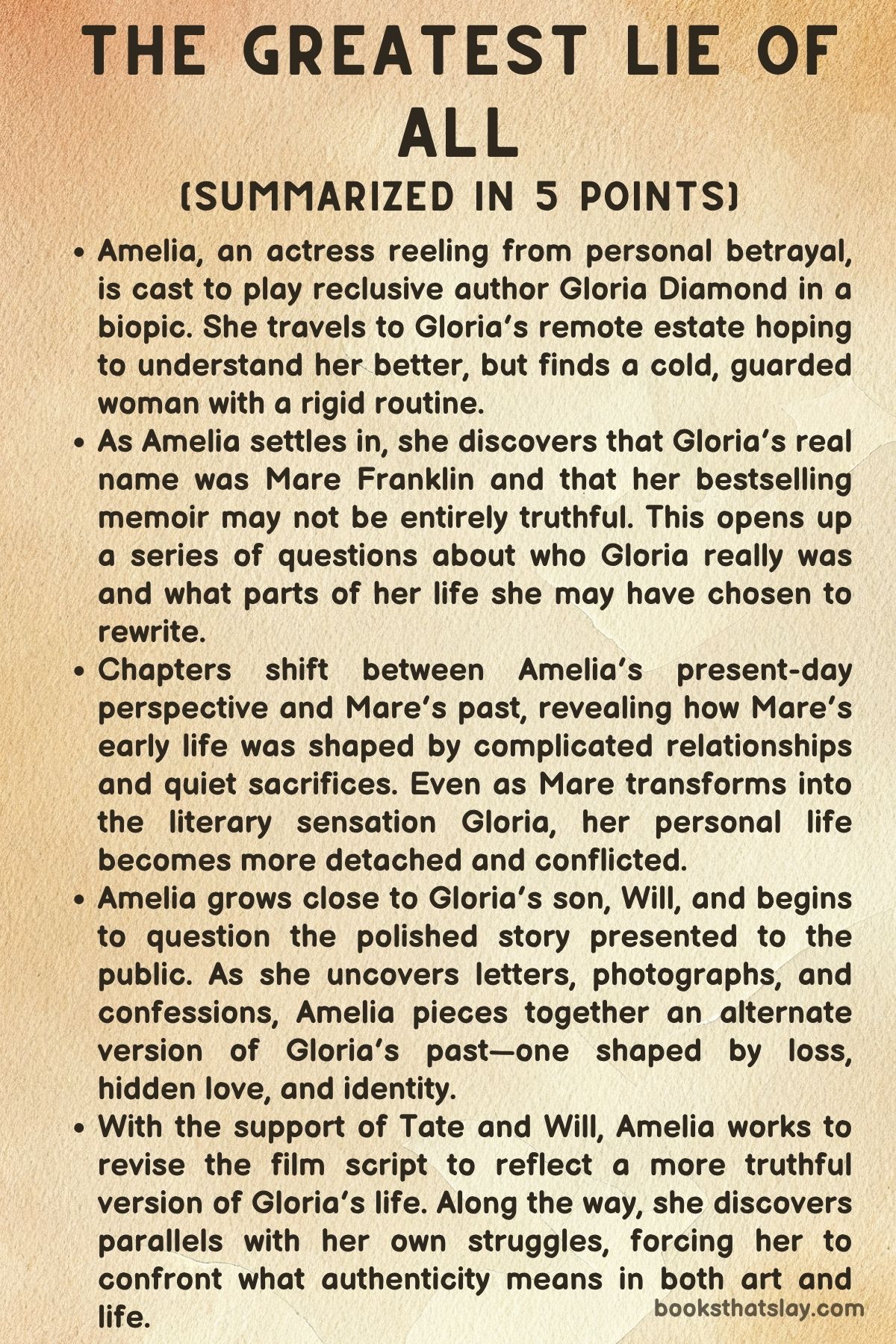

The Greatest Lie of All by Jillian Cantor is a layered narrative that bridges past and present, exposing how personal history and hidden truths can echo across generations. At its center is Amelia, a young actress reeling from betrayal and grief, who accepts a role that demands she embody the enigmatic romance novelist Gloria Diamond.

As Amelia immerses herself in Gloria’s life, she discovers that Gloria was once Mare Franklin, a woman with a history far more complicated than her novels admit. Through dual timelines and unraveling secrets, the story explores how women navigate trauma, love, ambition, and the roles they are expected to play—on screen, on paper, and in life.

Summary

Amelia Grant is an actress in freefall. Grieving her mother’s recent death and reeling from the discovery that her famous boyfriend Jase has been cheating on her, she abandons Los Angeles and her public life.

Three months later, she accepts a role that promises a fresh start: portraying famed romance novelist Gloria Diamond in a biopic. Determined to portray the woman authentically, Amelia travels to Gloria’s secluded estate to study her firsthand.

But instead of the charismatic literary icon Amelia expected, she meets a cold, reclusive figure who enforces rigid boundaries and seems haunted by an untold past.

Gloria limits their interactions, preferring quiet and solitude. Her assistant Tate offers Amelia more warmth and comfort, quietly encouraging her to dig deeper.

Amelia becomes fascinated by the tension between Gloria’s romantic public persona and her icy private demeanor. She begins sneaking around the house during Gloria’s nightly TV ritual, hoping to discover who the real woman behind the myth is.

When she finds an old photo of Gloria with an unidentified man taken after her marriage, she suspects the glamorous love story Gloria wrote about may not be true.

Amelia also meets Gloria’s adult son Will, who initially regards her with suspicion but slowly becomes a confidant. He reveals painful childhood memories that contradict Gloria’s published accounts.

He encourages Amelia to uncover the truth, even if it tarnishes the legend. Their connection deepens into something romantic, adding emotional stakes to Amelia’s investigation.

As Amelia unpacks Gloria’s secrets in the present, the story also traces Gloria’s origin through Mare Franklin in the early 1980s. Mare is a college student when she reluctantly begins dating George, a man she doesn’t love but stays with out of loneliness.

Her best friend Bess, deeply in love with her own boyfriend Max, becomes the emotional anchor in Mare’s life. Despite her feelings for Max, Mare pushes him toward Bess.

After a night of blurred consent with George, Mare finds herself pregnant and, lacking support, marries him. Their relationship is cold and controlling, and Mare’s life becomes defined by isolation and regret.

Years later, Mare attempts to reclaim her life. Her marriage to George has turned emotionally abusive, and she seeks refuge in Max, who has reentered her life.

She dreams of escaping with Max and their son Will, but their plan is upended when a tragic car accident kills Max and leaves Mare hospitalized. Will survives, but Mare wakes to discover Bess is pregnant, possibly with Max’s child.

Confronted with guilt and heartbreak, Mare chooses silence over confrontation. She buries her past, reinvents herself as Gloria Diamond, and rewrites her history as a tale of everlasting love with George.

Back in the present, Amelia uncovers layers of personal involvement in the story she thought she was merely portraying. A photograph of her own mother, Bess, in Gloria’s home sets off a cascade of revelations.

Amelia realizes that her mother was once deeply entwined with Gloria and Max. Through conversations, letters, and painful memory recovery, she pieces together the truth: her childhood memories, including the night of a gas explosion that killed George, are fragments of a much bigger story.

As a child, Amelia—then Annie—saved Will from the fire, a moment buried under trauma and secrecy.

Gloria, now old and ailing, finally offers Amelia a manuscript—The Real Gloria Diamond. In it, she confesses the truth behind her public persona: the abuse she endured, the choices she made out of fear, and the love she lost.

She admits she loved both Max and Bess, and regrets silencing her true story for the sake of a palatable myth. The manuscript becomes Gloria’s final act of truth-telling, her attempt to free herself and those she loved from decades of lies.

The final pieces fall into place when Amelia takes a DNA test to confirm whether Max is her biological father, as Gloria suspects. The results reveal that Gaitlin, the man who raised her, is indeed her biological father, but the emotional impact of the question still reverberates.

Meanwhile, Amelia and Will confront the tangled history between their families and choose to move forward together. Their bond, forged in the fires of the past, offers a future defined by honesty and love rather than myth and performance.

In the closing chapters, Amelia finds a letter from her mother to Gloria, never sent but brimming with emotion and unspoken love. She mails it to Gloria, giving both women the closure they never had.

Gloria, in return, brings Will to Amelia’s doorstep, accepting their relationship and making peace with her past. The story ends with Amelia embracing a future built on the truth, love, and the freedom to live authentically—no longer burdened by the lies that once defined the lives of Mare, Bess, and Gloria Diamond.

Characters

Amelia Grant

Amelia Grant is the emotional anchor of The Greatest Lie of All, a woman navigating the overlapping losses of her mother and her identity. Initially reeling from heartbreak and grief, Amelia’s journey is a study in emotional reinvention.

Her boyfriend’s betrayal and her mother’s death strip her of safety and self-understanding, forcing her into the uncertain terrain of autonomy. When she takes on the role of Gloria Diamond in a film, she approaches it as more than a performance—it becomes a vehicle for rediscovery.

Amelia is at once ambitious and vulnerable, sharp-witted but emotionally raw. As she immerses herself in Gloria’s life, she begins to excavate her own, uncovering forgotten trauma, family secrets, and buried truths.

Her transformation is not purely artistic but deeply personal. The parallels between her life and Gloria’s emerge subtly, especially through her connection to Will and the eventual revelation of her mother Bess’s connection to Mare.

Amelia evolves from a passive sufferer of heartbreak to a determined seeker of truth. Her courage surfaces not only in her pursuit of authenticity but also in confronting buried pain, resisting false narratives, and choosing love that feels real.

By the end, she represents a new generation willing to break the silence that shaped the lives of the women before her.

Gloria Diamond / Mare Franklin

Gloria Diamond, formerly Mare Franklin, is the novel’s most complex and haunted figure. A famed romance novelist, she is a woman who has mythologized her pain into fiction, using her pen to mask the traumas of her youth.

Mare’s life is defined by choices rooted in fear, duty, and repression. Her early experiences with love—particularly with Max—are intense but ultimately sacrificed for security, leading her into a loveless, often abusive marriage with George.

Gloria’s transformation from Mare to the glamorous, composed queen of romantic fiction is a desperate act of self-preservation. She becomes a symbol of survival through self-invention.

Yet, beneath her poised exterior lies deep regret, especially about the relationships she suppressed or distorted, including her feelings for Bess. Her interactions with Amelia force her to confront her legacy—not as a celebrated author but as a flawed human being.

Through her final manuscript, she reveals the woman she truly was, offering herself and others the grace of honesty. Gloria’s character is a profound meditation on how people rewrite their stories not just to deceive others, but to survive the unbearable.

Bess

Bess is a pivotal, though often shadowed, figure in The Greatest Lie of All, acting as both Mare’s best friend and the mother of Amelia. Initially presented as a secondary presence in Mare’s early life, Bess gradually emerges as a central emotional force.

Her relationship with Mare is layered with unspoken love, rivalry, loyalty, and heartbreak. It is Bess who introduces Mare to George, unknowingly setting in motion a tragic chain of events.

Her own romantic involvement with Max adds complexity, revealing a web of overlapping affections and betrayals. Bess represents the path not taken, the confidante who perhaps loved Mare more deeply than either could admit aloud.

Even after Mare chooses silence over revelation, Bess remains tethered to her, symbolically and emotionally. The discovery of Bess’s letter and her photograph among Gloria’s belongings confirms a love story that was hidden in the margins.

Her quiet presence lingers like a ghost, shaping both Mare’s regrets and Amelia’s awakening. Through Bess, the novel explores themes of hidden desire, maternal mystery, and the emotional residue of choices made decades earlier.

Will

Will, the son of Mare and George, straddles the dual roles of witness and participant in the unfolding drama. As a child, he endures a turbulent home defined by parental conflict, and as an adult, he remains haunted by that instability.

In the present timeline, Will is cautious and defensive, protective of his mother yet skeptical of her curated legacy. His relationship with Amelia starts as strained but gradually softens into trust, then intimacy.

Will provides emotional clarity and a grounding presence for Amelia, contrasting sharply with her ex, Jase. Through Will’s memories and insights, Amelia begins to unearth contradictions in Gloria’s story, and in doing so, finds both connection and clarity.

Will’s own arc is marked by quiet resilience. He grapples with the truth about his parents, his father’s abusive behavior, and the mysterious role Max may have played in his early life.

Despite the emotional weight he carries, Will chooses to step into love without defensiveness, signaling a new generational capacity for healing. His reunion with Amelia in the epilogue reflects a hopeful closure, built on truth rather than illusion.

Max Cooper

Max is a romantic specter haunting every corner of The Greatest Lie of All. A charismatic and passionate figure from Mare’s youth, Max represents the love that might have been—the freedom she longed for but never claimed.

His presence in Mare’s life is brief but impactful, igniting a sense of possibility and passion that her life with George never offers. Though Mare introduces Max to Bess and steps aside, her feelings for him never truly fade.

Their affair, rekindled years later, underscores the enduring pull of unfinished love. Max’s tragic death in a car accident—under suspicious and emotionally charged circumstances—becomes a turning point that propels Mare into deeper repression.

The suggestion that George may have caused Max’s death adds a layer of psychological violence to Mare’s already fraught marriage. Max is the truth that Mare buried under her constructed persona, and the presence she could never quite erase.

His love remains her greatest risk and her greatest loss.

George

George, Mare’s husband, is the embodiment of emotional control, violence, and patriarchal entitlement. From their earliest interactions, George’s relationship with Mare is transactional and coercive, lacking true emotional depth.

His sexual assault of Mare sets a grim precedent for their marriage, which becomes increasingly joyless and isolating. George is manipulative and emotionally abusive, using guilt, obligation, and later, alcohol-fueled intimidation to control Mare.

His rage culminates in a gas explosion that likely represents a final act of twisted self-destruction. George is both a symbol and a catalyst—a man whose domination shaped Mare’s silence and trauma.

His eventual death is not just a plot point, but a metaphorical release from decades of repression, opening the door for Mare’s reawakening as Gloria.

Tate

Tate, Gloria’s assistant, is a quiet but significant presence in the present-day narrative. Kind, observant, and loyal, Tate serves as a subtle bridge between Gloria’s past and Amelia’s search for truth.

While she respects Gloria’s boundaries, she also subtly encourages Amelia’s curiosity, offering cryptic hints and emotional support. Tate’s role is not simply to maintain Gloria’s household, but to protect her emotional boundaries while quietly yearning for the truth to be known.

She symbolizes the compassionate witness—someone who sees without interfering and cares deeply without demanding resolution. Tate’s presence underscores the tension between loyalty and silence, making her a quietly powerful force in the unraveling of Gloria’s story.

Jase

Jase, Amelia’s ex-boyfriend, plays a comparatively small yet crucial role in triggering the novel’s emotional trajectory. His betrayal—caught in the act of infidelity—shatters Amelia’s illusion of love and safety.

Jase is self-absorbed, opportunistic, and emblematic of performative relationships that lack true depth. His presence looms through the film set and even in Gloria’s home, as he once starred in the show she watches obsessively.

While he does not occupy much narrative space, Jase functions as the foil to Will, representing Amelia’s past choices born of surface appeal rather than emotional substance. His early betrayal catalyzes her search for something deeper, more enduring, and ultimately more authentic.

Themes

Reinvention as a Means of Survival

Amelia and Gloria’s journeys in The Greatest Lie of All underscore how reinvention becomes an essential survival mechanism in the aftermath of trauma and disillusionment. Mare, who later becomes the mythologized Gloria Diamond, begins as a woman navigating powerlessness, betrayal, and emotional stagnation.

Her early choices—to marry George despite the lack of passion, to suppress her feelings for Max, and to distance herself from Bess—stem from fear and necessity rather than desire. But after enduring emotional abuse, the loss of love, and the collapse of her dreams, Mare chooses to erase her past and construct a new self.

Gloria Diamond is not just a pen name; she is a persona, a carefully crafted identity that allows Mare to gain control over her narrative and build a career centered on fantasy rather than painful truth.

Amelia’s reinvention is less theatrical but no less profound. Abandoned by her boyfriend and grieving her mother, she accepts the role of Gloria in a biopic, thinking it will revitalize her stagnant career.

But the role becomes a mirror, revealing Amelia’s own vulnerabilities and prompting her to reflect on who she is without the identities imposed by grief, betrayal, and societal expectations. Like Gloria, Amelia begins to shed her former self—not by crafting fiction, but by digging into the truth.

While Gloria rewrites her past to survive, Amelia confronts the past to reclaim authenticity. Their parallel transformations illuminate how identity is never fixed but constantly shaped by experience, trauma, and the stories we choose to tell—or bury.

The Burden of Silence

Silence—both chosen and imposed—is a corrosive force in the lives of the characters, dictating relationships, altering truths, and shaping destinies. Mare’s silence begins with her inability to speak out against George’s sexual coercion and emotional manipulation.

Over time, this silence deepens as she hides her love for Max, buries the truth about their brief affair, and conceals her anguish over his death. Even more telling is her refusal to confront the emotional entanglement with Bess, choosing repression over honesty.

The cumulative effect of these silences is a life spent in quiet torment, ultimately demanding the invention of Gloria Diamond as a way to manage the dissonance between who she is and who she appears to be.

Amelia inherits this legacy of silence, not through direct trauma, but through omission. She grows up unaware of her mother’s deep ties to Gloria and the devastating events that shaped their lives.

Her entire identity rests on a foundation riddled with secrets. The discovery of her mother’s past, the photograph, the revelation of Max’s possible paternity—all unearth years of hushed pain.

When Amelia begins to piece together the truth, the emotional weight is overwhelming. She realizes that silence doesn’t protect people—it isolates them, corrodes trust, and distorts legacy.

The novel argues that confronting uncomfortable truths, even at the cost of dismantling cherished illusions, is the only way to reclaim agency and healing. Gloria’s final act of breaking her silence by writing The Real Gloria Diamond becomes a symbolic release, not just for her, but for Amelia and the generations bound by unspoken pain.

The Lies We Tell Ourselves and Others

The story exposes the deeply human tendency to create and cling to illusions—about love, family, and personal worth—especially when reality is too painful to endure. Gloria Diamond’s literary persona is perhaps the most striking example of this: a woman celebrated for writing sweeping romances about her enduring love for George, when in truth, their marriage was founded on convenience, coercion, and emotional vacancy.

This grand deception is not purely for public consumption—it becomes Gloria’s shield against her regrets, her lost love for Max, and the intimacy she was too afraid to pursue with Bess. Her bestselling memoir is a monument to a life that never existed, and yet it brings her fame, validation, and influence.

It is the greatest lie of all, not because it fools others, but because it allows her to function.

Amelia, too, confronts her own self-deceptions. Her relationship with Jase was a fantasy she maintained despite red flags, and her career—rooted in performance—demands a continual blurring of lines between truth and fiction.

As she unravels Gloria’s story, Amelia begins to see how lies can offer temporary comfort but ultimately rob people of real connection and self-understanding. The truth, even when painful, provides the only real chance for growth.

The contrast between Gloria’s fictitious narrative and her raw, confessional manuscript emphasizes the cost of deception. Through Gloria’s final honesty, and Amelia’s decision to live and love authentically with Will, the novel advocates for vulnerability over pretense, showing that the greatest act of courage is telling the truth—even when it breaks the stories we’ve built our lives around.

Generational Echoes and Inherited Trauma

The past in The Greatest Lie of All does not remain static—it reverberates through generations, shaping lives in unseen ways. Mare’s trauma—rooted in her coerced marriage, loss of Max, and complicated relationship with Bess—is never resolved but rather transformed into fiction and passed down to her son Will, who grows up amidst conflict and repression.

His childhood memories of hiding from fights and sensing emotional tension contradict Gloria’s public image, indicating that children internalize the emotional truths their parents suppress. Will’s emotional guardedness as an adult and his initial hesitance to trust Amelia reflect the residual damage of growing up in a house filled with unspoken grief.

Amelia’s inheritance is subtler but just as potent. Raised by Bess, who never revealed her own buried past with Mare and Max, Amelia enters adulthood with a fractured sense of identity.

Only through Gloria’s story does she uncover the depth of her mother’s sacrifices and the possibility of romantic feelings between Bess and Mare. These revelations alter Amelia’s understanding of love, loss, and family.

She learns that the emotional wounds of her predecessors live on in her, shaping her decisions, her capacity for intimacy, and even the roles she chooses to play. The generational cycle only begins to break when Amelia consciously chooses truth, intimacy, and forgiveness—both in her relationship with Will and in the way she interprets and embodies Gloria’s legacy.

The novel suggests that while trauma may echo across generations, so too can healing, if we are brave enough to listen to the past and write a different ending.

Love in Its Many Forms

Love in The Greatest Lie of All is not confined to romantic tropes—it is multifaceted, often messy, and shaped by circumstance, regret, and courage. Mare’s love for Max is passionate and sincere but thwarted by timing, fear, and external obligations.

Their bond is a portrait of what might have been, underscoring how love can be powerful and true yet still impossible to sustain. More complicated is Mare’s connection with Bess, which exists in a space between friendship and suppressed romantic desire.

Their emotional intimacy, loyalty, and unspoken longing suggest a form of love that society—and Mare herself—was unwilling to name or pursue fully. The possibility that Bess was the great love of Mare’s life adds a poignant layer to the story, revealing how love can be stifled not just by circumstance, but by internalized fear.

Amelia’s experience of love is shaped by betrayal and rediscovery. Her relationship with Jase was built on illusion and shattered by infidelity, leading her to question her own worth.

Her growing connection with Will, however, emerges as a kind of emotional salvation. It is rooted in honesty, shared vulnerability, and the recognition of each other’s wounds.

Their love is not grandiose but grounded, offering a vision of partnership that is healing rather than performative. In embracing Will, Amelia symbolically embraces her past, her identity, and the possibility of love without secrets.

The novel ultimately portrays love not as a sweeping narrative of fate, but as a series of conscious choices—to risk, to reveal, and to forgive. Whether romantic, maternal, or platonic, love in this story is a source of both ruin and redemption.