The House in the Cerulean Sea Summary, Characters and Themes

The House in the Cerulean Sea by T.J. Klune is a whimsical and heartfelt novel about finding family in the most unexpected places.

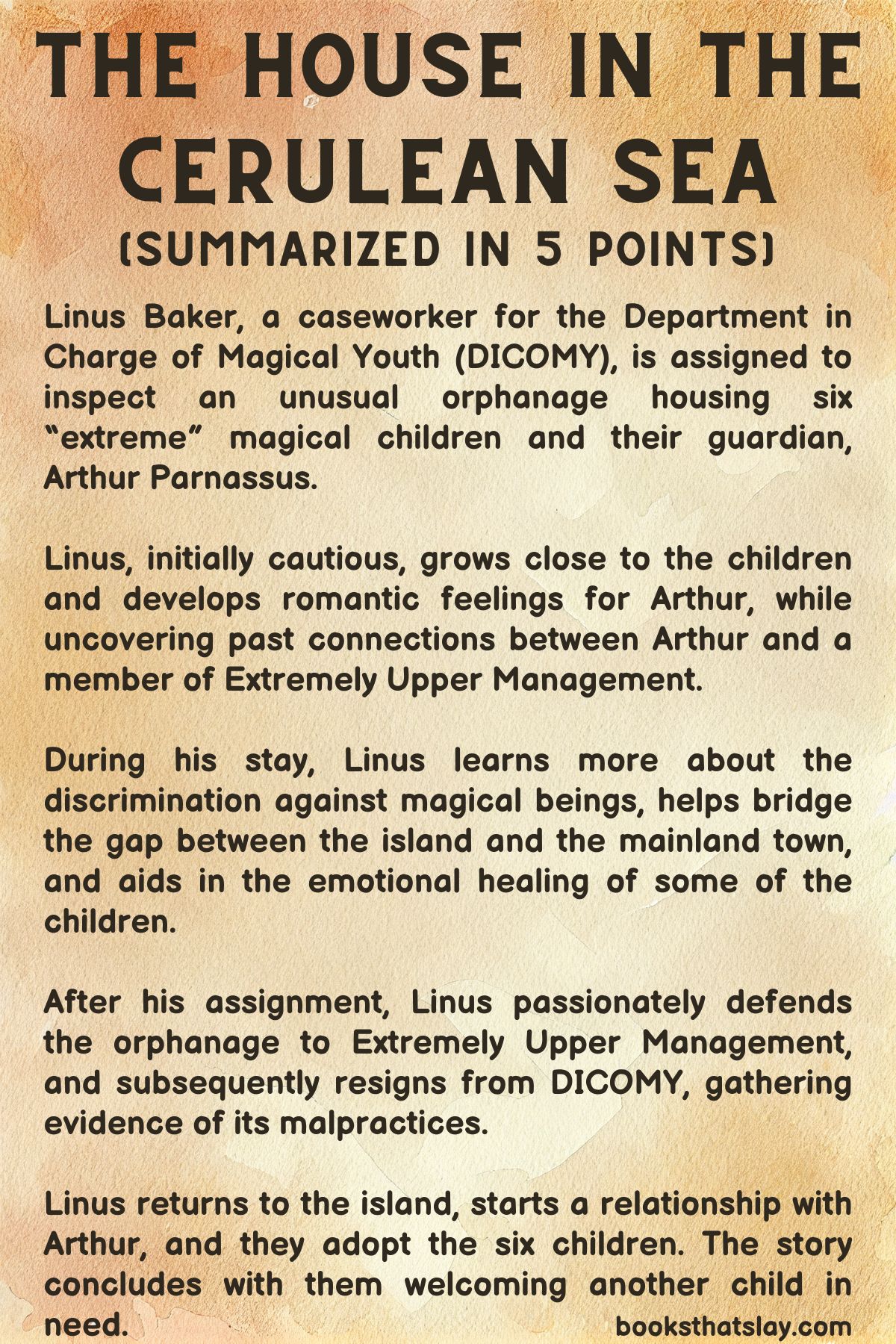

It follows Linus Baker, a meticulous and lonely caseworker for the Department in Charge of Magical Youth, who is sent on a top-secret mission to assess an orphanage on a secluded island. The children there are unlike any he’s encountered—including a mischievous gnome, a shapeshifting Pomeranian, and the literal Antichrist. But as Linus learns to see beyond rules and labels, he discovers a home filled with love, an enigmatic caretaker, and a life more magical than he ever imagined.

Summary

Linus Baker is a man of order, duty, and solitude. His days are spent buried in paperwork at the Department in Charge of Magical Youth (DICOMY), evaluating government-sanctioned orphanages for children with unusual and often dangerous abilities. He lives alone in a tiny house, his only company being his cat, Calliope, and his beloved collection of vinyl records.

His life is predictable—until one day, it isn’t.

Summoned by the shadowy figures of Extremely Upper Management, Linus receives an assignment unlike any before. He is to travel to a remote orphanage on Marsyas Island, home to six “high-risk” magical children.

The files provided are vague but alarming—one of the children, Lucy, is described as the spawn of the Devil himself. His guardian, Arthur Parnassus, remains a mystery, with barely any official record to his name. Linus is tasked with determining whether the orphanage is a threat to the world or a haven for the misunderstood.

Arriving on the island, Linus is immediately out of his depth.

The children are unlike anything he imagined—a sharp-witted gnome eager to bury him in her garden, a tiny wyvern obsessed with collecting buttons, a shy shapeshifter, and a sentient blob who dreams of being a bellhop.

And then there’s Lucy, a young boy with a flair for the dramatic and a love for rock music, who delights in terrifying Linus with apocalyptic proclamations. Overseeing them all is Arthur, warm and enigmatic, fiercely protective of his wards yet holding secrets of his own.

As days turn into weeks, Linus’s carefully constructed walls begin to crumble. He witnesses the bond between Arthur and the children, the quiet courage it takes to create a home in a world that fears them.

He finds himself standing up to the prejudiced villagers, advocating for the children’s right to belong. He grows closer to Arthur, sensing a connection he doesn’t quite know how to name. And then he stumbles upon the truth—Arthur is a phoenix, the last of his kind, once imprisoned in the very orphanage he now runs.

Faced with a choice, Linus does what he never expected: he fights. He challenges DICOMY’s policies, exposing the systemic cruelty inflicted upon magical youth.

And in doing so, he realizes that home is not a place but the people who welcome you in. Leaving behind the life he thought he was meant to live, Linus returns to Marsyas Island—not as a caseworker, but as family. In the end, love, in all its wild and wondrous forms, triumphs.

Characters

Linus Baker

Linus Baker begins The House in the Cerulean Sea as a man shaped by routine, rules, and quiet fear. He is a middle-aged DICOMY caseworker who has spent seventeen years training himself to be “objective,” which in practice means emotionally distant and professionally obedient.

His early scenes show how small his life has become: a cramped desk, a tiny home, lonely meals, a cat as his only confidante, and a deep habit of expecting punishment even for trivial mistakes. That ingrained anxiety makes him a perfect tool for the system—until he meets children who don’t fit the labels he has been taught to trust.

Linus’s arc is essentially the slow reawakening of empathy and courage. On Marsyas Island, he moves from cautious inspector to invested protector, learning to read people rather than files.

His relationship with Sal, helping move the desk into the daylight, marks a turning point: Linus starts acting on care instead of procedure. By the end, he openly challenges Extremely Upper Management, risks his job to defend the children, and chooses a life of belonging over safety.

Linus embodies the theme that goodness isn’t neutrality but active love, and his transformation is the moral engine of the story.

Arthur Parnassus

Arthur Parnassus is the heart and moral center of Marsyas Orphanage in The House in the Cerulean Sea. Outwardly, he is warm, theatrical in a gentle way, and unshakably patient; inwardly, he is fiercely protective and quietly radical.

Arthur understands that the world will always try to turn his children into threats or symbols, so he counters that narrative with daily rituals of care, structure, and joy. His leadership style blends tenderness with firmness: he corrects Lucy without shaming him, speaks to Talia in her own language to honor her dignity, and reassures Sal in ways that respect his trauma.

Arthur also carries the emotional burden of being the children’s only shield against institutional violence. His fear is not of the kids’ power but of the state taking them away, and that fear gives his kindness an edge of urgency.

When he challenges Linus’s belief in “objectivity,” Arthur is really arguing for moral responsibility—love that refuses to be passive. His romance with Linus grows not as a rescue fantasy but as recognition between two people who choose each other’s better selves.

Arthur represents the idea of chosen family and the insistence that nurture can outshine any dark origin story.

Zoe Chapelwhite

Zoe Chapelwhite, called Ms. Chapelwhite through much of The House in the Cerulean Sea, is brisk, sharp-tongued, and almost deliberately intimidating at first.

As an island sprite who predates human bureaucracy, she has no patience for DICOMY’s rules or the outsiders who arrive to judge children they don’t understand. Yet her severity is a form of guardianship: she wants to make it clear that the orphanage will not bend itself into palatable shapes for the comfort of fearful humans.

Over time, her humor and humanity show through—especially in her playful music-filled cooking scenes with Lucy and in the steady competence with which she maintains island life. Zoe also acts as a bridge for Linus.

She refuses to let him hide behind procedure, reminding him repeatedly that the children’s personhood is not negotiable. Her monologue at the train platform near the end carries the weight of her own past risks and losses, revealing that her cynicism was earned through experience, not bitterness for its own sake.

Zoe stands for the courage to live truthfully even in a hostile world, and her loyalty to Arthur and the kids is absolute.

Lucy (Lucifer)

Lucy is the most symbolically charged child in The House in the Cerulean Sea, introduced through a terrifying file label—Lucifer, Antichrist, son of the Devil—and immediately contrasted by his actual self: a six-year-old with flair, mischief, and a desperate hunger to be loved. Lucy performs “evil incarnate” theatrics partly because he enjoys drama, but more deeply because he has been taught that the world expects a monster, so he tries on that costume to control the fear it causes.

His intelligence is sharp and curious, and he tests Linus with pranks not to harm him but to find out whether this adult will flinch away like the others. Lucy’s nightmares reveal his vulnerability: his power is vast, but his greatest fear is abandonment and being lost.

The floating house and shattered records are not villainy but a child’s panic spilling into magic. Lucy grows because he is surrounded by adult steadiness—Arthur’s unconditional love, Zoe’s unafraid presence, and eventually Linus’s gentle reassurance.

He represents the book’s clearest argument against moral essentialism: origin and label do not determine character, and even the most frightening potential can be met with care instead of cages.

Sal (the shifter, were-Pomeranian)

Sal is the quiet emotional mirror of Linus in The House in the Cerulean Sea—reserved, wary, and shaped by a history of being uprooted. As a teen shifter who becomes a Pomeranian when startled, Sal embodies the instinct to make himself small in a world that has treated his existence as dangerous.

His room’s emptiness and the hidden desk in the closet show how he has learned to conceal not just his magic but his identity. Writing becomes his lifeline, the first space where he can narrate himself instead of being narrated by institutions.

Sal’s relationship with Linus is delicate and healing. He tests Linus with direct questions about being taken away because his trust has been broken before.

When Linus helps move the desk into the light, it is both a literal act and a symbolic invitation for Sal to exist openly. Sal’s courage is quiet rather than explosive; he does not suddenly become fearless, but he begins to believe that stability is possible.

He represents trauma survived through tenderness and the slow reclaiming of voice.

Talia (the gnome)

Talia is a tiny force of nature in The House in the Cerulean Sea, introduced with a threat and a shovel but revealed as deeply devoted to the living world she tends. She is proud, prickly, and intensely protective, using aggression as an armor against outsiders who might harm what she loves.

Her fierce attachment to the garden reflects her need for rootedness; soil and growth are her identity, her sanctuary, and her proof that beauty can be made and defended. Talia’s humor is sharp, often macabre, and she takes pleasure in startling Linus, yet beneath that is an astonishing capacity for care.

She knows the island and its people intimately and functions as a kind of sentry for the family, suspicious of strangers because she has learned what strangers can do. When Linus returns at the end, her tears and renewed threats show how much she had come to trust him despite herself.

Talia embodies loyalty that looks like ferocity, and she reinforces the theme that even the smallest person can be a guardian of home.

Theodore (the wyvern)

Theodore brings a gentler, more wordless emotional register to The House in the Cerulean Sea. As a small wyvern who hoards shiny objects, he might seem like comic relief, but his behavior is a child’s version of security: collecting treasures because they make the world feel stable and safe.

His instinct to demand a coin from Linus is not greed so much as a test of character and a ritual of belonging. Theodore communicates largely through action and affection, curling around ankles, chirping, and trusting the people who treat him kindly.

His tendency to steal Linus’s buttons becomes a running symbol of connection, with Linus gradually shifting from irritation to amused acceptance, reflecting the broader move from suspicion to family. Theodore represents innocence that doesn’t need to be translated into human norms to be understood, and his presence keeps the household grounded in playful warmth.

Phee (the forest sprite)

Phee in the novel is wonder made visible. She is young, cautious with strangers, and deeply attuned to the rhythms of the island.

Her magic is creative rather than destructive—listening to the earth and coaxing new flowers into existence—making her a living reminder that power can be an act of beauty. Phee’s distrust of Linus at first stems from learned experience; she has watched adults arrive with clipboards and leave with consequences.

Yet she is also curious, and as Linus proves himself, her wariness softens into a quiet acceptance. Phee reflects the book’s ecological tenderness: the idea that the natural world and the magical world are linked, and that listening is a form of respect.

She adds an almost sacred softness to the family dynamic, emphasizing that not all strength needs to be loud.

Chauncey (the tentacled boy)

Chauncey is one of the sweetest affirmations of identity in the the novel. As a green, tentacled child of unknown species who dreams of becoming a bellhop, he shows how dignity can be found in simple aspirations.

Chauncey’s politeness and delight in hospitality are not played for mockery inside the family; Arthur and the others honor his dream, allowing him to rehearse it daily, which gives him confidence and purpose. His enthusiasm in the village when he spots a real bellhop is pure joy, and it reframes ambition as something rooted in self-image rather than societal prestige.

Chauncey also offers moral contrast to the government’s fear: even a child who looks monstrous to outsiders is utterly gentle at heart. He represents the right to define oneself beyond appearances, and the safety that comes from being taken seriously.

Calliope

Calliope, Linus’s cat, functions as both companion and compass. She is stubborn, unimpressed by human drama, and fiercely independent, which mirrors the parts of Linus that still want a life larger than his rules.

Her escapades—stealing a tie, bolting into the garden, immediately bonding with the island children—constantly pull Linus into connection when he might otherwise retreat. Calliope’s comfort on Marsyas Island compared to her coldness on the return trip highlights where Linus truly belongs.

She is a quiet emotional barometer for his inner state, and her presence softens his isolation enough for change to begin. In a story about chosen family, Calliope is the first family Linus allows himself, and the first to lead him toward the rest.

Ms. Jenkins

Ms. Jenkins represents the cold face of bureaucracy in The House in the Cerulean Sea.

She is not a nuanced villain so much as a person wholly absorbed into the system’s logic. Her interactions with Linus are defined by suspicion, intimidation, and the constant threat of demerits, reinforcing how power operates through fear rather than reason.

She treats rules as moral truth, and that rigid dependence on hierarchy allows prejudice to pass as professionalism. Ms. Jenkins functions as a narrative pressure point: her pettiness and cruelty clarify why Linus’s eventual rebellion matters. She is an example of how ordinary people can become instruments of harm when they stop seeing individuals and start seeing only compliance.

Gunther

Gunther is a smaller but sharper embodiment of institutional rot in the novel. His smugness and eagerness to give demerits show a person who finds identity through enforcing control.

Unlike Ms. Jenkins’s authoritarian severity, Gunther’s cruelty is mean-spirited and personal; he delights in Linus’s discomfort and clings to small power because it flatters his ego.

He illustrates how systems of fear recruit not only leaders but also petty gatekeepers who keep oppression running through everyday humiliations. While not central to the emotional arc, Gunther’s presence makes Linus’s old environment feel claustrophobic and morally stale.

Mr. Werner

Extremely Upper Management, including Mr. Werner, serve as the faceless ideology of fear within The House in the Cerulean Sea.

They speak in the language of welfare and safety while practicing segregation, coercion, and dehumanization. Their questioning of Linus’s “detachment” is hypocritical; they want empathy only insofar as it strengthens their control.

Mr. Werner’s hinted personal stake and special focus on Lucy underline how prejudice often masks private agendas.

EUM’s refusal to see the children beyond their files is the core antagonistic force of the story. They are less characters in a personal sense and more a collective portrait of how institutions preserve power by branding difference as danger.

Linus’s confrontation with them is thus not only a plot climax but a thematic indictment of systems that confuse order with virtue.

Merle (the ferryman)

Merle is a minor figure in The House in the Cerulean Sea, but he embodies the everyday hostility that makes isolation necessary. His surliness, price-gouging, and fear of being on the island after dark show a man who has absorbed local prejudice and turned it into routine behavior.

He is not actively monstrous, but his reflexive contempt demonstrates how hate can become banal. Merle’s presence reminds the reader that the orphanage’s greatest threats are not the children’s powers but the community’s fear.

Helen

Helen appears late but carries thematic weight in The House in the Cerulean Sea. Practical, determined, and unafraid to confront hostility, she helps Linus return to the island and later brings the news of David the yeti.

Helen represents the widening circle of allyship: people outside the immediate family who still choose to do the right thing. She signals that the world beyond Marsyas can change, and that courage can be contagious.

Mrs. Klapper

Mrs. Klapper functions as a sharply drawn antagonist of small-minded normalcy in the novel.

She is nosy, judgmental, and obsessed with appearances and property value, which positions her as a comic but cutting symbol of societal pressure. Her relentless comments about Linus’s loneliness and conformity show how cruelty can be wrapped in the language of concern.

Linus snapping at her on his return is important not because she changes, but because he does. She represents the life Linus outgrows: a world where worth is measured by neat lawns, gossip-approved marriage prospects, and keeping everything “safe” by keeping everything the same.

Daisy and Marcus

Though they appear mainly in Linus’s earlier case, Daisy and Marcus help set the moral baseline of The House in the Cerulean Sea. Daisy is young, powerful, and emotionally learning how to hold that power; her accidental outburst comes not from malice but from the volatility of childhood feelings.

Her honesty with Linus and her immediate remorse show the possibility of responsibility without shame. Marcus, with his tail in a cast and his quick forgiveness, demonstrates resilience and communal repair rather than retribution.

Together they introduce the book’s central claim before Marsyas even enters the story: magical children are still children, and what they need is guidance, patience, and safe belonging, not fear.

Themes

Bureaucracy, power, and the cost of “safety”

From the opening inspection, the world of The House in the Cerulean Sea shows a system that treats magical children as risk categories before it sees them as people. Linus is trained to measure, record, and recommend, and his workplace reinforces the idea that distance equals professionalism.

The demerit culture, the endless handbook, and the looming fifth floor make the institution feel less like a protector and more like a machine that reproduces obedience. “Safety” becomes a slogan that justifies control: children are isolated on remote sites, their movements restricted, their caretakers watched for the smallest breach, and entire villages are bribed into silence.

The point is not care but containment. Even language is weaponized through files that define children by species, lineage, and threat level, as if identity can be reduced to a label in a folder.

The story highlights how such structures push ordinary people into complicity. Linus isn’t cruel, but he has learned to accept the rules as neutral.

His fear of supervisors and his reflex to self-blame show how power works in quiet ways: people internalize the system’s values so thoroughly that they police themselves. The EUM meeting makes the hierarchy explicit—Linus stands in a spotlight, literally beneath those who judge him, and is told what to see, what to report, and even what to fear.

Yet the longer he stays on Marsyas, the clearer it becomes that the system’s assumptions are not built on evidence but on prejudice fed by political anxiety. This is why his final confrontation matters: he refuses to translate living children into institutional language.

The later reforms and resignations only happen because someone steps outside the rules and exposes their harm. The theme argues that bureaucracy can disguise cruelty as procedure, and that real safety comes from responsibility and relationship, not surveillance and segregation.

Belonging, found family, and chosen commitment

The emotional center of the novel is the gradual creation of a family that is not defined by blood or legality but by care, daily rituals, and mutual protection. Marsyas Orphanage looks chaotic through an outsider’s eyes, yet its order comes from love expressed in ordinary routines: shared meals, learning moments at the table, tending the garden, mending records, moving a desk to a window.

The children are not passive recipients of shelter; they participate in shaping the home. Each child’s quirks and needs are held as part of a collective life rather than problems to be fixed.

Lucy’s theatrical darkness, Theodore’s hoard, Talia’s fierce pride, Sal’s guardedness, Chauncey’s dreams, and Phee’s trust in the earth all fit because Arthur and Zoe make space for them and also expect them to show up for one another.

Linus enters this environment starved for connection, even if he doesn’t admit it to himself. His city life is marked by solitude, self-containment, and relationships that are transactional or intrusive.

Marsyas gives him a model of belonging where he can be seen without being evaluated. The children’s curiosity about him, their teasing, and their fear of losing the home push him to recognize that he is already part of their world.

Sal asking for help moving the desk is a turning point in this theme: a small act of trust becomes a shared promise that home can be stable. Later, Lucy’s nightmare and Linus’s quiet comfort show belonging in crisis—family is what holds when fear erupts.

The final return to the island makes the theme explicit through action rather than sentiment. Linus chooses to resign, abandon his old house, and commit to a life where he can love and be loved.

The children set playful “terms” for accepting him back, which frames family as a mutual agreement, not a rescue fantasy. Arthur asking him to stay, and Linus agreeing, completes the shift from observation to participation.

Belonging here is not found by being assigned a place; it is built by choosing people and letting them choose you.

Difference, stigma, and the struggle to be seen clearly

Throughout the novel, difference is treated as a battleground between fear and understanding. The villagers’ hostile stares, the propaganda posters, the secrecy orders, and the classification of children as “dangerous” all grow from a culture that imagines the unknown as a threat.

The Antichrist label is the sharpest example. DICOMY insists that Lucifer’s identity predicts catastrophe, but the island community insists on a more human truth: Lucy is a child who wants attention, stories, dancing, and safety.

By letting both views collide in everyday life, the novel shows how stigma is maintained: through distance, through rumor, and through the refusal to learn who someone is beyond a stereotype.

The children themselves live under the weight of these stories. Sal’s constant worry about being moved again is not just personal trauma; it is a result of a world that has taught him he will never be accepted for what he is.

Talia’s readiness to threaten newcomers, Phee’s mistrust, and Lucy’s performance of evil all read as survival strategies. They have learned that outsiders arrive expecting monsters, so they meet that expectation on their own terms.

Yet the island also shows what becomes possible when difference is met without panic. Linus begins by clinging to files as if they are maps to reality, but repeated encounters undermine the assumptions built into those files.

He watches restraint in Daisy’s earlier case; on Marsyas, he sees more: self-control, kindness, creativity, and accountability. Even moments of danger, like Lucy’s nightmares, are framed not as proof of evil but as a need for care.

By the time Linus speaks to EUM, he refuses the idea that morality or destiny is biologically fixed. He names each child in full, asserting that their identities are richer than any single descriptor.

This naming is political as well as personal—stigma thrives on abstraction, and naming forces recognition. The theme makes a broader point about social prejudice: when institutions and communities reduce people to categories, they stop seeing growth, context, and individuality.

Acceptance in the book is not naïve optimism; it is the practice of looking again and again until fear no longer gets to define what is true.

Personal change through empathy and moral courage

Linus’s arc in the novel is not a sudden makeover but a slow loosening of habits that once felt like survival. At the start he is careful, nervous, and shaped by rules to the point that he measures his life in demerits and compliance.

He believes goodness is expressed through proper procedure, and he mistakes emotional distance for fairness. The island forces a different education.

He is repeatedly put in situations where the rulebook cannot tell him what a good person does: when a child trusts him with a secret room, when a nightmare shakes the house, when a village crowd turns cold, when management threatens him for asking questions. In each case empathy is not an abstract virtue but a choice with consequences.

The story shows how empathy becomes courage. Linus begins to write reports that reflect what he actually sees rather than what EUM expects.

He proposes taking the children into the village because he recognizes isolation as harm. He hides the warning memo from Zoe, a small act of loyalty that signals shifting allegiance.

The biggest change arrives after he returns to the city. The contrast between the stale house and the island’s warmth makes clear that the old version of Linus cannot hold.

His refusal to remove the photo from his desk is a moral line drawn in public. When he confronts EUM, he does not argue with clever policy language; he speaks from lived knowledge and refuses to accept their definitions.

What follows—smuggling files, resigning, giving away his home—shows that change is not only emotional but structural. He reorganizes his entire life around what he now believes is right.

The theme is careful to portray the cost: loneliness in the three weeks of waiting, fear of retaliation, the risk of losing his job and security. Moral courage here isn’t heroic posturing; it is persistence in the face of systems designed to exhaust dissent.

By the end, Linus’s happiness is inseparable from his values. He is not rewarded for obedience but for finally acting like the person he had the capacity to be all along.

Healing from trauma and protecting childhood

Many characters in the novel carry quiet, lasting wounds from a world that has treated them as disposable. The novel takes trauma seriously without turning it into spectacle.

Sal’s past uprootings, his instinct to make himself small, and his private writing all show a child trying to regain control over a life spent at others’ mercy. Lucy’s nightmares reveal how fear can live inside even the most outwardly confident child.

Talia’s defensiveness and Phee’s suspicion come from repeated experiences of hostility. Even Linus reflects another kind of trauma: emotional neglect and a life narrowed by anxiety and isolation.

Healing in the book is portrayed as relational and incremental. Sal doesn’t become trusting because someone tells him he’s safe; he tests safety through action.

Moving the desk is symbolic, but it is also practical: it puts his creativity in the sunlight rather than hidden away. Lucy’s healing begins when his terror is met with steadiness, not punishment.

Arthur holds him through the episode, the other children wait without panic, and Linus helps repair the records instead of scolding him. This reinforces a key idea: children learn to regulate fear when adults model calm presence.

Zoe’s role matters too, especially her insistence that Lucy is still a child no matter his origin. She refuses to let the adults around her forget what childhood requires: patience, boundaries that don’t humiliate, and faith in growth.

The theme also critiques environments that claim to protect children while actually harming them. DICOMY’s secrecy orders, the prohibition against leaving the island, and the constant threat of closure all keep children in a state of uncertainty.

The book suggests that stability is not a luxury but a requirement for childhood to flourish. In the epilogue, the plan to bring in David the yeti extends this theme forward: healing homes are not finite.

They adapt, make room, and keep choosing care. Childhood here is not defined by innocence but by potential, and protecting it means giving children space to be complicated, scared, joyful, and still worthy of love.