The House Is on Fire Summary, Characters and Themes

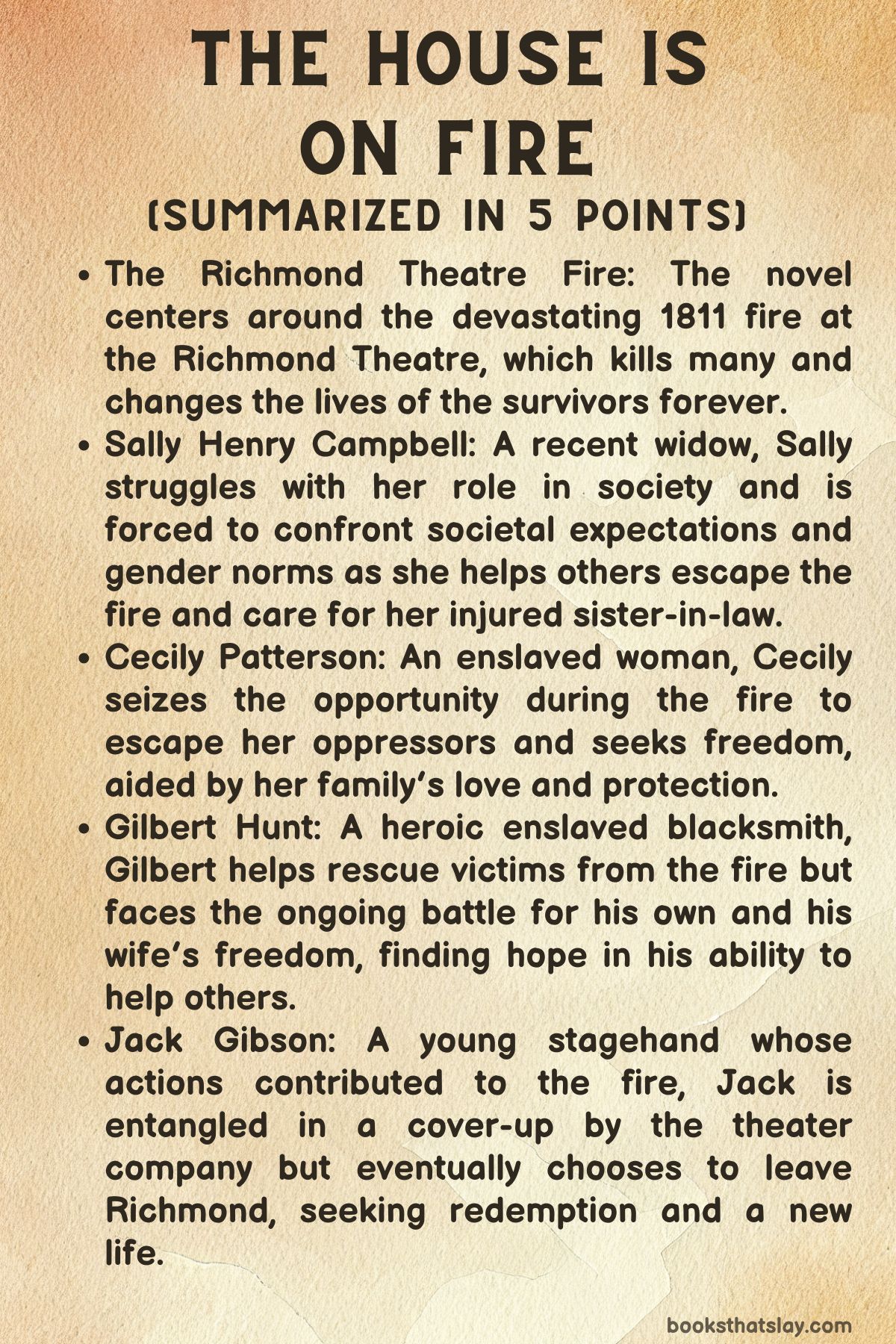

The House Is on Fire by Rachel Beanland is a gripping historical fiction novel set against the backdrop of the 1811 Richmond Theatre Fire. The story weaves together the lives of four main characters—Sally, Cecily, Gilbert, and Jack—each grappling with their own challenges in the wake of the devastating fire.

The narrative unfolds over just a few days but explores themes of survival, courage, societal constraints, and moral dilemmas. Through each character’s perspective, Beanland offers an emotionally charged and multifaceted look at one of America’s deadliest early disasters.

Summary

Set in 1811, The House Is on Fire begins on a fateful December night when a fire engulfs the Richmond Theatre, forever altering the lives of those who survive.

Four characters—Sally Henry Campbell, Cecily Patterson, Gilbert Hunt, and Jack Gibson—each experience the catastrophe in different ways, their stories intersecting as the community grapples with the tragedy.

Sally, recently widowed and struggling to find her place in a world where men dominate her decisions, attends the theater with her in-laws, Margaret and Archie. Despite the evening’s promise of escape, Sally soon faces the chaos of the fire. She and Margaret are separated from Archie during the scramble to flee, and Sally becomes determined to rescue her sister-in-law.

Together, they break windows to help others escape, ultimately jumping themselves. Sally survives relatively unscathed, but Margaret’s leg is broken, complicating their ordeal in the days following the fire.

As Sally navigates this traumatic experience, she begins to question the societal norms and gender dynamics that have long constrained her, drawing unexpected strength from her encounter with Mr. Scott, a mysterious theatergoer who also survives the fire.

Cecily Patterson, an enslaved woman, views the disaster as an opportunity for freedom. Assigned to chaperone her enslaver’s daughter, Maria, at the theater, Cecily becomes aware that her oppressors believe she perished in the fire.

Seizing the moment, she escapes into the wilderness, leaving behind her life of subjugation and torment. In a daring plan orchestrated with the help of her uncle, Gilbert Hunt, Cecily embarks on a journey northward, toward freedom.

Throughout her escape, Cecily’s courage and determination are sustained by her family’s love and protection, even as her life teeters on a knife’s edge.

Gilbert, a blacksmith who is also enslaved, finds himself in the midst of the rescue efforts, pulling victims from the flames alongside Dr. McCaw.

Despite his heroic deeds, he remains trapped in the confines of enslavement, his efforts to secure freedom for his wife, Sara, thwarted by their enslavers.

As he helps Cecily flee Richmond, Gilbert’s hope for the future persists, despite the crushing reality of his own circumstances.

Meanwhile, Jack Gibson, a 14-year-old stagehand, bears a heavy burden of guilt as he realizes his role in sparking the fire. Tasked with raising a malfunctioning chandelier, Jack is caught in the theater company’s attempts to avoid blame, with talk of a false conspiracy involving a slave revolt.

As he wrestles with the weight of his involvement, Jack eventually makes the decision to leave Richmond, seeking a new beginning away from the theater company and the lies it perpetuates.

In the aftermath of the fire, each character confronts the harsh realities of the world they live in, while finding hope, growth, and a sense of agency in their respective journeys.

The novel ends with their futures still uncertain, yet shaped by the resilience and determination that helped them survive the fire.

Characters

Sally Henry Campbell

Sally Henry Campbell is a recent widow and the daughter of the famed American revolutionary Patrick Henry. Her journey throughout The House Is On Fire reflects her personal and emotional evolution as she grapples with the trauma of the Richmond Theatre Fire and the patriarchal confines of her time.

At the beginning of the novel, she appears as a woman defined by her familial roles and obligations—having leaned on her sister-in-law Margaret for support after her husband’s death. During the fire, Sally showcases remarkable resilience and bravery, demonstrating her ability to stay calm under pressure.

Her actions—rescuing Margaret, Mr. Scott, and aiding others—hint at her capacity for leadership, compassion, and selflessness. In the aftermath of the fire, Sally’s disillusionment with the men around her, particularly her brother-in-law Archie and other figures in her social circle, grows as she witnesses their apathy or incompetence in the face of crisis.

This disillusionment crystallizes as Sally observes how Archie refuses to consider the amputation of Margaret’s leg, potentially endangering her life. These experiences prompt Sally to rethink the societal roles that men and women play, especially in terms of control and autonomy.

Her bond with Mr. Scott, who initially comes across as disagreeable, evolves into one of mutual respect, offering Sally a glimpse of a different kind of relationship. By the end of the novel, Sally is determined to write her own account of the fire, an act that symbolizes her newfound agency and desire to assert her voice.

Cecily Patterson

Cecily Patterson is one of the most complex and harrowing characters in the novel. As an enslaved woman on the verge of being given to her rapist, Elliott Price, as a wedding gift, Cecily’s story centers on survival, resistance, and ultimately liberation.

Her character arc captures the brutal realities of slavery, particularly the sexual violence endured by enslaved women. However, Cecily also embodies the fierce will to escape her fate.

The fire becomes a pivotal turning point for her—an unexpected opportunity to flee. Her decision to run away is driven not only by a desire for personal freedom but also by her rejection of a life marked by repeated victimization.

Cecily’s strength is reinforced by her family, particularly her mother Della and her brother Moses, who protect and aid her in her escape. The revelation that Elliott has been committing incest against his half-sister further complicates Cecily’s relationship with the Prices and the institution of slavery.

By exposing Elliott and fleeing Richmond, Cecily rejects the dehumanization she has endured and claims control over her destiny. Though she leaves behind the people who love her, her departure symbolizes not just physical freedom but emotional liberation from the oppressive systems that sought to break her spirit.

Gilbert Hunt

Gilbert Hunt is a heroic figure within the novel, characterized by his bravery, integrity, and deep commitment to his loved ones. An enslaved blacksmith, Gilbert plays a key role in rescuing people during the fire, including the valiant Dr. McCaw.

His selflessness is emphasized through his actions, as he tirelessly helps save others despite the risks to his own life. However, Gilbert’s heroism is tinged with the harsh realities of his status as an enslaved man.

Though he is celebrated for his bravery, his owner, Cameron Kemp, still treats him as property, and despite others’ efforts to buy his freedom, Kemp refuses to sell him. Gilbert’s relationship with his wife, Sara, and his determination to buy her freedom speaks to his enduring hope and commitment to building a future together.

His love for Sara is a major motivator throughout the novel, as he tries to secure their freedom and build a life independent of their enslavers. His involvement in Cecily’s escape further underscores his protective and familial instincts, as he risks everything to ensure her safety.

Although Gilbert ends the novel in jail and without securing Sara’s freedom, he retains a sense of hope, believing that their love and determination can still carve a path to a better future.

Jack Gibson

Jack Gibson’s character arc reflects the burden of guilt, moral conflict, and the eventual quest for redemption. As a 14-year-old orphan working as a stagehand for the Placide and Green Theater Company, Jack is initially caught up in the routine of his job.

His concern over the malfunctioning chandelier goes ignored, and when the fire breaks out, Jack is thrust into the center of a conspiracy. The guilt of knowing that he played a role in raising the chandelier that ultimately caused the fire weighs heavily on Jack.

His culpability becomes even more entangled with the company’s attempts to cover up their negligence by falsely blaming the fire on an enslaved revolt. Jack’s internal conflict grows as he realizes the magnitude of the disaster and its impact on innocent lives, including that of his mentor, Professor Girardin, who loses his family in the fire.

Jack’s story is one of personal awakening as he wrestles with the temptation to preserve his job and future by going along with the company’s lies versus standing up for the truth. His final decision to walk away from Richmond and the theater company marks his attempt to reconcile with his guilt and find a new path.

While Jack does not receive the punishment or justice he may feel he deserves, his departure suggests a fresh start and an opportunity for self-forgiveness.

Themes

The Collision of Personal Agency and Systemic Oppression in Times of Crisis

One of the novel’s most intricate themes is the tension between personal agency and the inescapable constraints of systemic oppression, especially in times of crisis. The fire serves as the literal and symbolic catalyst that thrusts each of the four main characters into situations where they must confront their lack of control over their lives.

Cecily’s enslavement forces her to make a life-or-death decision to flee when the opportunity presents itself, highlighting how moments of chaos can offer temporary breaks from rigid social hierarchies. Gilbert, though also enslaved, uses his heroic actions during the fire to challenge the moral conscience of those who still see him as property.

Even his temporary elevation as a “hero” does not escape the grim reality of his enslavement. For Jack, the stagehand, the fire places him at the mercy of a power structure (the theater company) that seeks to cover up the truth and scapegoat the vulnerable.

Sally’s conflict arises not just from the fire but from her growing realization of the inequities embedded in the genteel, male-dominated world she inhabits. The novel illustrates how systemic oppression—whether rooted in race, class, or gender—continues to shape and constrain individuals, even when a sudden catastrophe seems to offer them the chance to assert their agency.

The Dehumanizing Nature of Social Hierarchies and the Consequences of Inherited Power

A pervasive theme in The House Is On Fire is the dehumanizing effect of social hierarchies, particularly those based on slavery, gender, and class, which perpetuate cycles of cruelty, control, and violence. Cecily’s storyline exposes the cruel dehumanization of enslaved individuals, with her life being manipulated as property—most disturbingly in Elliott’s repeated sexual abuse and his family’s callous plans to “gift” her to him.

This shows how social power, handed down through generations, enables moral degradation, as those in power see human lives as objects to be exploited. Similarly, Gilbert’s interactions with his enslaver, Cameron Kemp, demonstrate how even the most heroic deeds cannot transcend the systemic structures that define enslaved people as less than human.

Sally’s internal transformation, as she observes the suffering around her, becomes a critique of the aristocratic class’s detachment from the realities of those beneath them. The novel challenges the idea that inherited power leads to moral superiority, showing instead that those with power often perpetuate violence and exploitation.

Whether it’s through direct ownership of others, like Kemp, or more subtle forms of control, like Elliott’s domination of his family, the novel explores how power corrodes human relationships and perpetuates cruelty across generations.

The Ethics of Survival and the Morality of Self-Sacrifice in a World Without Justice

Another complex theme is the ethical struggle between survival and self-sacrifice in a world that offers little justice, especially for those at the margins. For Cecily, survival demands not just physical escape but a complex navigation of familial ties, personal identity, and moral resilience.

Her flight to freedom represents not only escaping physical captivity but also an ethical struggle to redefine her existence on her own terms, even as she leaves behind those she loves. Gilbert’s heroism during the fire is driven by an intense personal morality, but it is not enough to change the harsh reality of his or his wife’s enslavement.

The novel explores how acts of self-sacrifice—like Gilbert’s saving of countless lives—exist in tension with the need to fight for one’s own survival and freedom. For Jack, the fire forces him into a moral dilemma: should he protect himself by lying or face potential consequences by speaking the truth?

Jack’s ultimate decision to leave the company and Richmond represents an ethical stand, but it’s a bittersweet victory. The larger structures of power remain intact. The novel suggests that survival and morality are often at odds, particularly when the broader societal framework is unjust.

The Intersection of Gender, Power, and Moral Agency in a Patriarchal Society

The novel carefully interrogates how gender, power, and moral agency intersect within a patriarchal society, particularly through the character of Sally. As a widow and the daughter of Patrick Henry, Sally initially seems to occupy a privileged position in Richmond society.

However, the novel reveals the limitations of her power in a world where men like Archie control decisions about life and death, such as the refusal to amputate Margaret’s leg. Sally’s journey is not only about physical survival but also about her awakening to the limitations imposed on her gender.

Her growing dissatisfaction with the men in her life—especially Archie—and her bond with the initially cold Mr. Scott suggest a reevaluation of what constitutes moral strength and agency in a male-dominated world. The novel critiques the patriarchal structures that infantilize women, deny them medical autonomy, and confine their roles to passive, socially acceptable spheres of influence.

Sally’s decision to begin writing her account of the fire signals her assertion of intellectual and moral authority. She challenges the societal norms that would keep her voice marginalized, exploring how women must carve out their own forms of power in a world that largely refuses to recognize them.

Trauma, Memory, and the Rewriting of Personal and Collective Histories

The House Is On Fire delves into the theme of trauma and memory, not just as a personal experience but as something that shapes collective histories. The fire itself is a traumatic event for all the characters, but each processes and reacts to it differently.

Sally’s decision to document the events is emblematic of a desire to control the narrative surrounding the fire. She seeks to provide an alternative version to the male-dominated accounts that would likely emerge.

The novel portrays memory as something malleable and contested, as evidenced by Jack’s internal struggle with the theater company’s attempt to manipulate the narrative of the fire’s cause by blaming it on enslaved people. Jack’s eventual rejection of the false narrative shows how trauma can compel individuals to either distort or confront the truth.

Cecily’s escape represents her literal rewriting of her history—she rejects the future that Elliott and the Prices have laid out for her, taking control of her destiny and her memory of self. The novel suggests that while trauma can fracture individuals, it can also serve as a powerful force for rewriting both personal and collective histories.