The House of Doors Summary, Characters and Themes

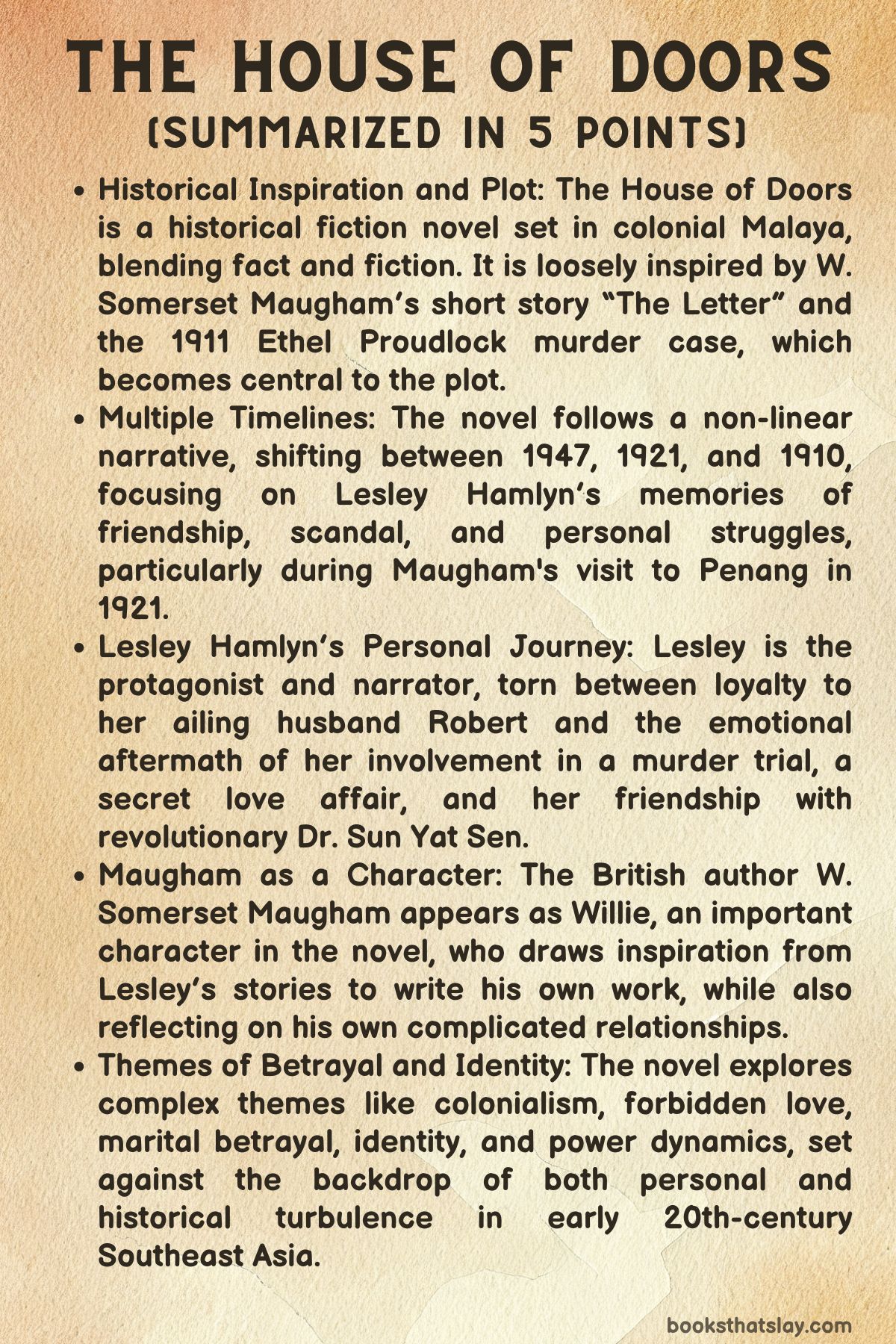

The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng is a captivating blend of historical and literary fiction that intertwines real-life events with fiction, set in early 20th-century colonial Malaya. Loosely inspired by W. Somerset Maugham’s short story “The Letter,” it delves into themes of love, betrayal, and colonial tension, centering on the infamous 1911 Ethel Proudlock case.

Maugham himself features as a character in the story, and the novel skillfully navigates multiple timelines, exploring the complexities of relationships, identity, and the consequences of personal choices against the backdrop of historical events and social upheaval.

Summary

In The House of Doors, Tan Twan Eng weaves a rich, nonlinear narrative that spans decades, moving between 1910, 1921, and 1947. The novel follows Lesley Hamlyn, a British woman living in colonial Malaya, as she reflects on pivotal moments of her life and her involvement in two intertwined stories of betrayal and scandal.

The novel begins in 1947, in South Africa, where Lesley, now widowed, receives a copy of W. Somerset Maugham’s The Casuarina Tree. As she glances at the photographs of her past, memories from 1921 resurface, particularly of Maugham’s visit to Penang.

Maugham, referred to as Willie in the novel, had come to Penang during a financially difficult time in his career, hoping to revive his fortunes.

Lesley recalls the conversations she had with him, including her connection to Dr. Sun Yat Sen, a revolutionary she once admired, and her lingering suspicions about Willie’s relationship with his secretary, Gerald Haxton.

In 1921, Lesley is hesitant to join her husband Robert in South Africa, despite his need for a healthier climate after being injured in World War I. Their marriage has suffered from hidden secrets, and Lesley contemplates the growing distance between them.

As she interacts with Maugham, she finds herself telling him about her friend Ethel Proudlock, who had been involved in a scandalous murder trial in 1910. Ethel’s case—killing a man she claimed attempted to assault her—unfolds as a layered and tragic story of deceit.

Lesley confides to Maugham the shocking revelation that Ethel’s victim had been her lover and that she had been coerced into the murder by her father and husband.

This revelation sparks Maugham’s interest, as he sees the potential for a story that could restore his waning literary fame.

Lesley’s tale of Ethel’s trial is also intertwined with her complex feelings for Dr. Sun Yat Sen and her personal entanglements. In 1910, Lesley had met Sun and been drawn to his revolutionary ideas, which led her into a clandestine romance with Arthur Loh, a Chinese associate of Sun.

As tensions rise in her marriage, she discovers her husband Robert’s own secret affair with his male assistant, Peter Ong, leaving her deeply conflicted and questioning the nature of love, loyalty, and fidelity.

Ethel’s trial, a public spectacle, ends in her conviction, but she is eventually pardoned by the Sultan of Selangor, leading to racial and colonial tensions within the British expatriate community.

As Lesley navigates her emotions, Robert grows increasingly ill, leaving her to reflect on the choices they both made during their time in Malaya.

By 1921, Willie is inspired by Lesley’s confessions and begins crafting a story based on her experiences, though it risks exposing her secrets. Lesley, feeling the weight of the past, decides to leave for South Africa with Robert, seeking a fresh start.

Years later, in 1947, after Robert’s death, Lesley revisits her memories, now tempered with regret, and contemplates returning to Penang to reconnect with Arthur Loh, the man who had once captured her heart.

Characters

Lesley Hamlyn

Lesley Hamlyn is the novel’s protagonist and narrator, whose character is deeply nuanced and defined by internal conflict and societal constraints. In 1921, she is depicted as a woman grappling with her place in a world governed by patriarchal expectations.

Her complex relationship with Robert, her husband, is tinged with resentment, as she feels bound by the responsibilities imposed on her by marriage. Lesley’s fascination with Dr. Sun Yat Sen, which hints at a possible emotional or intellectual affair, suggests her yearning for freedom, both from her husband and from societal norms.

She is intelligent and empathetic, traits highlighted through her compassionate feelings toward Ethel Proudlock and the injustices faced by women. Her eventual affair with Arthur Loh also speaks to her need for emotional fulfillment and rebellion against the restrictions of her life.

Lesley’s decisions, particularly her reluctance to testify truthfully in Ethel’s defense and her decision to go to South Africa with Robert, highlight the tensions between loyalty, societal pressure, and personal desires. In her later life, as depicted in 1947, Lesley becomes reflective and nostalgic.

Her memories of her past, especially her relationships with key figures such as Maugham, Ethel, and Dr. Sun, suggest a deep sense of regret and longing. She is a character burdened by secrets and a life of unfulfilled potential, which gives her a sense of melancholy.

Robert Hamlyn

Robert Hamlyn, Lesley’s husband, is a man shaped by societal expectations of early 20th-century British colonialism. He adheres to conservative values, particularly in his attitudes toward race and marriage, and his relationship with Lesley is strained due to his infidelity.

Robert’s affair with Peter Ong, a Chinese man, introduces complexity, revealing his own internal struggle with societal norms and personal desires. His ill health, caused by his experiences in World War I, adds further tension to his marriage with Lesley.

Despite the strain, Robert’s remorse over Ethel’s treatment and his eventual peaceful relationship with Lesley show that he is capable of growth and emotional vulnerability. These moments of change in his character are brief but significant.

Willie (W. Somerset Maugham)

Willie, a fictionalized version of the British author W. Somerset Maugham, plays a central role in The House of Doors. As a visiting writer, Willie faces the pressures of his literary career while forming personal connections in Penang.

His suspicion that Lesley had an affair with Dr. Sun reveals his own preoccupation with secrets, desire, and betrayal—themes explored in his writing. Willie’s relationship with his wife, Syrie, and his lover, Gerald Haxton, highlights his struggles as a gay man in a conservative society.

His affair with Gerald reflects his need for financial stability and artistic success while maintaining a socially unacceptable relationship. Willie’s interactions with Lesley reveal mutual respect and intellectual camaraderie, though his contemplation of writing about her life adds a layer of rivalry.

His moral dilemma—whether to write about Lesley’s story, knowing it will bring him fame at her expense—captures his internal conflict as a writer. Ultimately, Willie’s role underscores the theme of storytelling and its power to reshape reality.

Ethel Proudlock

Ethel Proudlock is based on the real-life figure involved in the 1911 murder trial. Her story of deception, betrayal, and societal pressure is central to the novel’s plot.

Ethel is a victim of her circumstances and the men in her life—her father, her husband, and her lover, William Steward. Her refusal to admit to her affair with Steward, even when it could exonerate her of murder, reflects the immense societal pressures on women of the time.

Ethel’s friendship with Lesley provides insight into both women’s struggles against societal judgment. Ethel’s conviction and eventual pardon highlight racial and gender inequalities in the British colonial system, reflecting the biases that dictate her fate.

Arthur Loh

Arthur Loh, a Chinese nationalist and member of the Tong Meng Hui, serves as a political and romantic figure in Lesley’s life. His affair with Lesley challenges the racial and societal norms of British colonial society.

Arthur’s passion for the revolutionary cause is matched by his tenderness toward Lesley, showcasing his duality. His collection of intricately carved doors, housed in the metaphorical “House of Doors,” reflects his complex identity, moving between the worlds of Chinese and British influence.

Arthur’s involvement in Dr. Sun’s revolutionary activities adds to his complexity as a character. His relationship with Lesley, though passionate, is marked by the larger forces of history and societal constraints that pull them apart.

Dr. Sun Yat Sen

Dr. Sun Yat Sen, former president of China, is a charismatic and magnetic figure in Lesley’s life. His revolutionary ideals and political activities in Penang fascinate Lesley, drawing her into the world of Chinese nationalism.

Sun’s interactions with the Hamlyns, particularly Lesley, serve as a challenge to the rigid British colonial norms. His polygamy and political ideologies force Lesley to question her own values about marriage and power.

Sun’s deportation from Penang marks the end of his influence in Lesley’s life, symbolizing the impermanence of their relationship. Though he captivates her, his world remains distant and unreachable.

Gerald Haxton

Gerald Haxton, Willie’s lover and secretary, is a subtle yet significant figure in the novel. His relationship with Willie highlights the hidden lives of gay men in early 20th-century colonial societies.

Gerald is both a companion and enabler of Willie’s literary ambitions. His presence emphasizes the themes of secrecy, desire, and the tension between public and private lives.

Gerald’s role adds depth to Willie’s character, showing the complexities of navigating a relationship that defies societal expectations. Through his character, the novel explores the consequences of living in a world of hidden truths.

Themes

The Complex Intersection of Colonialism, Race, and Cultural Identity

In The House of Doors, Tan Twan Eng delves into the intricate power dynamics and tensions of colonialism. He uses the setting of British Malaya as a space to explore how colonial rule affects not only governance but also personal relationships, identity, and societal structures.

Through the interactions between the British and the native Malaysians, Eng reveals the racial hierarchies that undergird colonialism. The Europeans, including Lesley, Robert, and the British expatriate community, exhibit an ingrained sense of racial superiority over the Malaysians.

This manifests in Robert’s discomfort with Lesley’s associations with Dr. Sun Yat Sen and Arthur Loh. His fears stem from both a concern over her involvement in political uprisings and his own racist attitudes.

Lesley’s fascination with Sun, meanwhile, is entangled with her struggle to reconcile her attraction to a culture that British rule seeks to suppress. The novel presents colonialism not just as a political or economic system but as a pervasive force that penetrates intimate relationships and personal identities.

This challenges individuals to navigate their loyalties to race, culture, and power.

The Fragility of Marriage and Gender Roles within a Patriarchal Society

Marriage in The House of Doors is depicted as a fragile institution weighed down by the expectations and constraints imposed by patriarchal society. Lesley Hamlyn’s marriage to Robert serves as a central examination of the oppressive roles women are expected to fulfill within marriage.

Lesley’s disillusionment with her marriage, particularly after discovering Robert’s affair, reflects the broader disenchantment women experience. This is especially true in marriages where their identities are suppressed or compromised for the sake of social and familial stability.

This theme is also evident in the Proudlock case, which exemplifies how women are victimized by marriage. Ethel Proudlock is forced to commit murder under pressure from her father and husband, underscoring the extreme ways in which women’s agency is denied.

Marriage is not a private bond between two people in the novel. It is deeply influenced by societal expectations, gender roles, and the personal costs women bear to maintain these structures.

The Ethical Dilemma of Truth, Memory, and Storytelling

Tan Twan Eng weaves an intricate meditation on the ethics of storytelling, truth, and memory. This is particularly evident through the character of W. Somerset Maugham (fictionalized as Willie) and his role as both a character and a storyteller.

Willie’s relationship with Lesley is fraught with the ethical complexities of transforming lived experiences into stories for public consumption. As Lesley recounts the events surrounding Ethel Proudlock’s trial and her own personal life, Willie grapples with the morality of using these intimate revelations for his own writing.

Storytelling itself becomes a moral dilemma: it offers artistic and financial survival for Willie but risks betraying the confidences of his friends. The novel raises the question of who owns a story and whether fiction can ever truly capture the complexities of human experience.

The nonlinear narrative structure further emphasizes this theme. It illustrates how memory is fragmented, subjective, and constantly shifting over time.

Sexuality, Queerness, and the Hidden Lives of Colonial Subjects

The theme of hidden sexuality, particularly queer identities, runs throughout The House of Doors. It serves as a critique of colonial society’s oppressive norms and the constraints placed on personal identity.

Robert Hamlyn’s affair with Peter Ong, as well as Willie’s relationship with Gerald Haxton, underscores the clandestine nature of queerness. In early 20th-century colonial society, same-sex desires must be concealed in a culture that publicly condemns them.

Robert’s relationship with Peter Ong, a Chinese man, not only reflects his personal hidden desires. It also subverts the racial and colonial hierarchies of the time.

Willie’s relationship with Gerald operates more openly in certain circles but still remains veiled in secrecy. Eng explores how queerness challenges traditional structures of marriage, power, and race. He shows how colonial subjects must navigate both their public personas and private desires in a world that denies them full expression of their identities.

Political Revolution and the Role of Individual Agency within Historical Forces

Set against the backdrop of political upheaval in Malaya and China, The House of Doors presents a meditation on revolution, personal agency, and the broader currents of history. The novel juxtaposes individual lives, such as Lesley’s and Ethel’s, with the sweeping political changes embodied in figures like Dr. Sun Yat Sen.

Lesley’s attraction to Sun’s revolutionary ideals reflects her yearning for personal liberation from the confines of her marriage and colonial life. Yet, her involvement in the political movement is tempered by her personal conflicts and limitations as a colonial subject.

The novel interrogates whether individuals can effect meaningful change in a world dominated by larger historical forces. Lesley’s ultimate inability to fully align with the revolution underscores the tension between personal agency and the overwhelming power of historical and political movements.

While Dr. Sun becomes a symbol of revolutionary change, the characters remain caught in the tides of colonial history. They are unable to fully transcend their roles within the established order.

The Role of Orientalism and Exoticism in Western Perceptions of the East

The House of Doors engages critically with the Western exoticization of the East, particularly through the character of W. Somerset Maugham and his literary career. Willie’s interest in Lesley’s story of Dr. Sun and her involvement in Malayan political life is underpinned by a fascination with the “exotic” elements of Eastern life.

The novel critiques this Orientalist gaze by showing how Western writers and travelers like Willie view the East through a romanticized lens. They treat its people and cultures as material for stories rather than engaging with them as equals.

Lesley’s own fascination with Sun is also tinged with a degree of exoticism, though her personal involvement complicates this dynamic. Tan Twan Eng challenges the reader to consider how Western perceptions of the East often reinforce colonial hierarchies and stereotypes.

Through this theme, the novel critiques the cultural commodification and aestheticization of the East in Western literary traditions.