The Hunger We Pass Down Summary, Characters and Themes

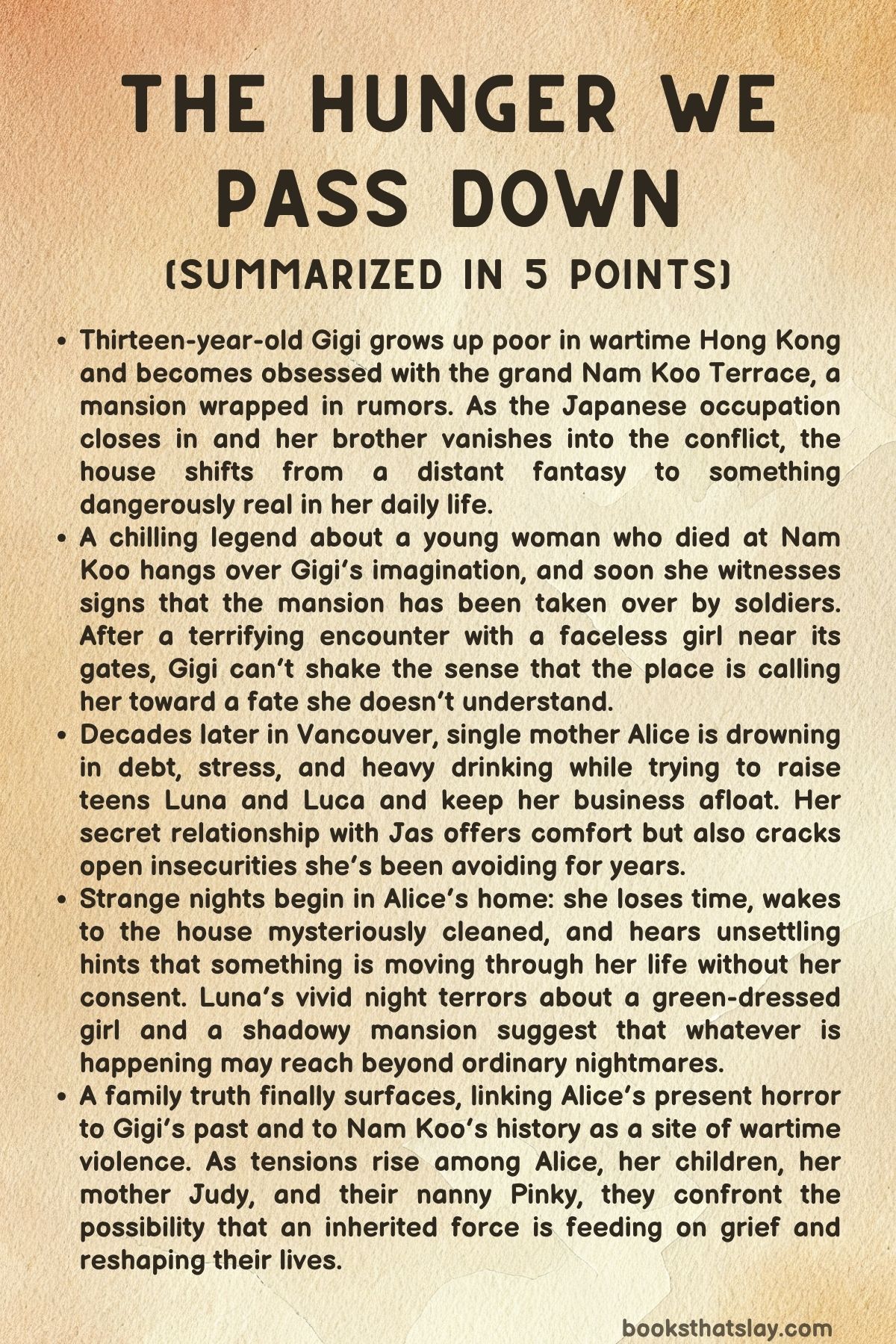

The Hunger We Pass Down by Jen Sookfong Lee is a multigenerational horror novel about what families inherit when history is too painful to name. It moves between wartime Hong Kong and contemporary Vancouver, following women and girls who sense something wrong in their homes long before they understand why.

The book pairs a real historical site—Nam Koo Terrace, used during the Japanese occupation—with a present-day family struggling with grief, addiction, and motherhood. Through ghosts, doubles, and nightmares, it asks how violence echoes across bloodlines, and what it costs to finally look straight at the past.

Summary

Thirteen-year-old Gigi lives in Wan Chai, Hong Kong, in a tight apartment with her mother and older brother. Their father has been gone for years, and money is always short.

On her daily walk to school she passes Nam Koo Terrace, a mansion so famous that people speak its name like a charm. Gigi is fascinated by it.

The high white walls, the deep garden shade, the ironwork, and the expensive cars in the driveway feel like proof that another kind of life exists—one that has nothing to do with her own cramped home or her mother’s exhaustion. Gigi’s brother teases her for staring and repeats the local rumor that the house is haunted only to stop trespassers.

Gigi doesn’t care. She keeps imagining what it would be like to live inside.

At school, Sister Lucia tells the class why Nam Koo is feared. Long ago a wealthy silk merchant built it for his young bride.

They had three sons and a gifted youngest daughter. Greedy for influence, the merchant arranged for that daughter to marry the son of a shipping tycoon.

The girl was only sixteen and desperate to avoid the match. She tried to escape the night before the wedding, was caught, locked in her room, and found dead the next morning, hanging from the chandelier.

Since then, people claim her spirit wanders the halls, sometimes crying, sometimes appearing with her head hanging loose or missing entirely. The story scares the other students, but for Gigi it mixes dread with curiosity.

She feels the mansion calling to her.

A year later, the war closes in. Radio broadcasts warn that the Japanese are coming.

Gigi’s brother joins the army and disappears into secret work behind enemy lines. Neither Gigi nor their mother knows where he is.

Their mother tries to sound proud and tells neighbors he is a spy, but Gigi senses the story is a shield against helplessness. At dinner she stares at his empty chair.

His absence stacks on top of the older loss of their father, leaving Gigi with a hollow ache she doesn’t know how to express.

With her brother gone, Gigi walks alone and lingers by Nam Koo when she wants. One afternoon she sees something new: people moving out while Japanese soldiers stand watch at the driveway.

The mansion has been taken. In the yard a young girl in a pale green dress holds a suitcase and looks back at the house like she’s being pushed away from it.

When Gigi accidentally makes a sound, the girl turns. Gigi realizes the girl has no face—just smooth emptiness where eyes and mouth should be—yet the girl’s attention feels direct and heavy.

Gigi is terrified and runs.

For weeks she avoids the mansion, choosing longer routes, but the faceless girl is stuck in her mind. One rainy afternoon she stays late at school sewing costumes for a play.

It’s nearly five o’clock when she leaves, and she panics about getting home in time to start the rice before her mother returns. She takes the shortcut past Nam Koo, telling herself not to look.

As she reaches the driveway, arms seize her from behind. Her umbrella falls.

Rain hits her legs, mud splashes her shoes, and she is dragged uphill into the house. She keeps her eyes shut, sensing that whatever is happening will not stop.

Later she will understand that this is the last moment she tries to hide from reality.

Decades later and across the ocean, the story shifts to Vancouver. Alice is forty, a single mother raising two kids: fourteen-year-old Luna and ten-year-old Luca.

She lives in the same house where her father, a photographer, once worked and died. His presence is everywhere—his pictures, his darkroom, the garden he loved—so the house already feels full of memory.

Alice runs an online cloth-diaper business that once boomed but now leaves her drained, in debt, and barely holding things together. Her ex-husband Grant, a politician with bigger ambitions, takes the kids on weekends and speaks to them sharply.

Alice’s mother Judy drops off groceries and worries, but also criticizes and nags. Alice soothes herself with nonstop work and too much alcohol.

She also has a secret relationship with Jas, a younger bartender she meets late at night and keeps hidden from the children.

After one weekend with Grant, Luna has a night terror. In the dream she runs through a dark forest, hears moaning, sees her grandmother’s face melt away, and ends up at the porch of a grand mansion.

A girl in a vivid green dress stands in the doorway. When Luna reaches for her, the girl shoves her down the steps and warns her in Cantonese to stay away and never come back.

Luna wakes shaken and then hears moaning again in the house. She creeps toward her mother’s door and overhears Alice laughing with a man.

Realizing her mother is having sex with someone, Luna recoils, angry and unsettled. The dream and the overheard sounds fuse into a sense that something is wrong under their roof.

That night Alice and Jas sit in a makeshift pillow fort in her bedroom, drinking wine and tequila. Jas asks for more commitment and wants to meet her family.

Alice freezes. She cares about him but fears disrupting the fragile order she has with her kids.

Jas, hurt, leaves and bluntly warns her about her drinking and chaos. Alone, Alice drinks more and slips into a blackout-like vision of childhood and her dying father.

She wakes the next morning hungover and confused by a spotless house and neatly packed diaper orders ready for pickup. She doesn’t remember cleaning.

Pinky, the former nanny who rents the basement suite, says she heard Alice working before dawn and suggests the memory loss might be from alcohol. The unexplained tidiness keeps happening, giving Alice more time but scaring her with the possibility she is losing control.

A big lifestyle brand called the Good You contacts Alice for diaper samples and a possible feature, sparking hope. She celebrates with Jas, but the night is tense and soaked in drink.

Later Alice remembers another gap from childhood: a feverish day when her father died, bruises on her wrists, her mother screaming. The old blank spaces line up with the new ones, making her feel hunted by something she can’t name.

At dim sum, Alice presses Judy about what’s going on. Judy finally reveals a family secret: Alice’s great-grandmother was a comfort woman during World War II, raped by Japanese soldiers at Nam Koo Terrace.

Judy says the women in their line have carried anger and haunting ever since. The revelation ties Luna’s dream, Alice’s blackouts, and the mansion’s history into the same root.

Soon Luna has another night terror, this time seeing her mother rip a man’s head off and calmly beckon her. Pinky, awake in the basement, hears strange thumping.

She finds Alice in the office at night, mechanically wrapping diapers under a weak bulb. When Alice turns, her face is distorted: a pulsing hollow where her nose should be, shadowed eyes, and a long tubular tongue.

Alice crushes a spider and licks her hand. Pinky flees, remembering her grandmother’s warnings about aswang—night creatures that wear human skin by day.

The narrative returns to Hong Kong in 1944–45. Gigi is imprisoned inside Nam Koo, now used as a comfort station.

She is forced into sexual slavery. Auntie powders the girls and orders smiles, but Gigi resists, goes rigid, and is beaten until soldiers stop choosing her.

She escapes into the garden when she can, imagining a future she cannot picture clearly. A package arrives with her old record and a note from her brother saying he has died.

When the war ends, the soldiers vanish, Auntie disappears, and only a few girls remain. Gigi is pregnant again.

She gives birth in the kitchen to a daughter, naming her Bette. Planning to flee, Gigi is confronted in the garden by the faceless girl, who reveals a face identical to Gigi’s.

The double snatches the baby and runs. Gigi begs to be taken instead.

Old Yan later finds her dead, hanging from a tree with a green silk sash. The baby is gone.

Years later Bette grows up as an orphan in Hong Kong, bullied as a “whore’s daughter” and half-Japanese. She keeps Gigi’s diary and a ring of Nam Koo keys.

She later emigrates to Vancouver, marries William, and lives beside a cemetery in a house filled with poverty and William’s rage. The family line continues, carrying secrets that never turn into words.

Back in present-day Vancouver, Luna searches online and finds Nam Koo Terrace, recognizing it from her dreams. Alice wakes to find Jas in her bed, with no memory of inviting him.

An argument spills outside, Grant confronts Jas, and Luna witnesses the fight. Alice collapses for days.

Luca, working on a science-fair security system, explores the basement and finds Judy hiding old boxes: the diary and the antique keys. He later finds claw gouges in a backyard tree and a broken pale claw tip, proof that something has been digging near their home.

One dawn Alice wakes in the front yard with dirt on her feet and broken nails. Grant is found unconscious and badly injured by the backyard gate.

In the hospital he insists Alice attacked him and says a woman was after Jas. Footage from Luca’s security app shows a figure identical to Alice dragging Jas across the garden at 2:43 a.

m. At Judy’s condo, the family and Pinky argue.

Judy admits she was pregnant with twins, one of whom died before birth. The placenta had two lobes and was buried in their backyard under rocks where nothing ever grew.

Judy also reveals she has cancer. Alice decides to return to the house with Luna and Pinky.

They dig up the burial site and find only a stained blanket and dried fragments. They rebury it with an apology to the lost twin.

Then Alice doubles over in pain and expels grey jelly onto the lawn. She sees a decayed woman with her own face, long talons, and a narrow tongue.

Pinky can’t see it. The twin attacks, slashing Pinky.

Alice fights back, stabbing the twin in the nasal hollow. A flashback shows that this twin emerged once before when Alice was sick as a child and murdered her father.

In the backyard the twin pins Alice and forces her and Luna into a mock family pose. Through shared visions it explains that it feeds on the family’s pain, grows through women’s fear, and has been doing Alice’s night labor.

Now it wants the men Alice loves—Jas and Luca—in payment. Alice tells Luna to run.

The twin drags Alice toward the rock pile, but Luna comes back and rejects its claim. Luca appears with a machete, attacks, and is killed when the twin smashes his head on the rocks.

In fury and grief, Luna takes the machete and cuts off the twin’s head. The head disappears, leaving blood and stones.

Alice, Luna, and Pinky escape.

In 2025, after the house is sold and Luca is buried, Alice and Grant reunite in shared grief. Luna goes to summer camp on Galiano Island and begins dating a boy.

One evening she feels a cold taloned hand on her stomach and realizes she is pregnant. Understanding that the hunger of the past has not ended but shifted onto a new body, she screams.

Characters

Gigi

Gigi begins as a thirteen-year-old girl whose inner life is shaped by scarcity and longing. Her daily walk past Nam Koo Terrace becomes a ritual of imagination and desire: the mansion represents everything her cramped apartment and unstable family cannot provide—space, safety, glamour, and choice.

What makes Gigi emotionally vivid is the way she clings to wonder while living amid abandonment. Her father’s departure has already taught her that men can vanish without explanation, and when her brother leaves for the army, that lesson deepens into a daily ache she cannot name but feels physically at the dinner table.

Gigi’s fascination with the mansion is not simple curiosity; it is a child’s survival strategy, a way to project herself into a life untouched by hunger, fear, and the volatility of her mother’s moods. When she is seized and dragged into Nam Koo, the narrative transforms her from a dreamer into a witness and victim of history.

Inside the comfort-station horror, Gigi’s refusal to perform cheerfulness and her stiff resistance to assault show a will that remains intact even when her body is controlled. Her later pregnancy and the quiet, almost numb planning of escape with Old Yan reveal a girl forced into adulthood by violence, yet still holding a thin thread of hope for her child.

The final confrontation with the faceless double, and Gigi’s choice to offer herself so Bette can live, crystallizes her as a figure of desperate maternal love and inherited sacrifice. She becomes the origin point of the family’s haunting, not because she is weak, but because her suffering is so profound it reverberates across generations.

Gigi’s brother

Gigi’s brother functions as both protector and absence, and his character is defined less by direct scenes than by the emotional space he leaves behind. Early on, he is impatient, pragmatic, and embarrassed by ghost stories, which positions him as a teenager already trained to distrust fantasy in a world that punishes softness.

His irritation at Gigi’s staring suggests he feels responsible for keeping her grounded, perhaps because he senses how vulnerable she is. When the war comes and he joins the army, his departure is not framed as heroic triumph but as another fracture in a family already brittle.

The rumor that he is a spy becomes a story the mother needs to survive, while Gigi quietly recognizes it as a coping myth. His note announcing his death arrives like a final severing, yet it also signals that he tried to reach her, to leave something of himself behind.

As a character, he embodies the tragic trajectory of young men in wartime—pulled toward duty, swallowed by secrecy, and transformed into memory. His disappearance intensifies the novel’s theme that love can be present even when bodies are not, and that absence itself becomes a kind of haunting.

Gigi’s mother

Gigi’s mother is a portrait of exhaustion and volatility produced by abandonment and poverty. She works as a secretary, holding the household together with fragile, constantly threatened balance, and her emotional unpredictability is rooted in fear rather than cruelty.

The way Gigi rushes to start the rice before her mother returns shows how the home has become a place where small failures carry outsized consequences. Her mother’s insistence that the brother is a spy reveals a mind that must reshape reality to avoid collapse; she cannot tolerate the helplessness of not knowing where he is, so she invents a narrative that gives his absence purpose.

Her character echoes later in Alice’s life: she is part of the lineage of women who survive by hardening, who express love through control because the world has repeatedly taken away what they relied on. Even when she is not physically present in later historical sections, her influence persists as one more layer of inherited tension, emphasizing how trauma does not end with the event but continues through family patterns.

Sister Lucia

Sister Lucia serves as a conduit between folklore and lived reality. When she tells Gigi the legend of Nam Koo Terrace, she introduces the novel’s central framework: the idea that women’s suffering in patriarchal systems becomes story, then ghost, then inheritance.

She is not just a teacher narrating a spooky tale; her authority gives the myth emotional weight, and her version of the legend foreshadows the truth Gigi will later endure. Sister Lucia represents the institutional voice that keeps cultural memory alive, even if it is softened into parable for schoolchildren.

Through her, the book shows how history is transmitted in fragments—half warning, half mourning—and how children receive those fragments before they understand what they mean.

Alice

Alice is the contemporary mirror to Gigi, but her suffering is shaped by a different landscape: not open war, but the daily grind of grief, debt, and single motherhood. At forty, she is surrounded by the memory of her dead father, so her haunting begins as grief embedded in objects—photos, darkroom tools, garden remnants—before it becomes something supernatural.

Her online cloth-diaper business reveals her as driven and capable, yet also trapped by the very success that promised freedom; the business leaves her exhausted, financially precarious, and unable to stop working. Alice’s most defining feature is her emotional fragmentation.

She drinks to numb isolation, keeps her relationship with Jas hidden to preserve the illusion of stability for her children, and cycles between tenderness and sharp defensiveness when overwhelmed. Her blackouts and the unexplained housework dramatize her fear that she might be losing herself, either to alcoholism or to something older that lives in her blood.

When Judy reveals the family’s Nam Koo trauma, Alice becomes the point where buried history erupts into the present. In the final confrontation, her character sharpens into clarity: she is willing to face the twin, accept the truth about her family, and fight even when she doubts her own innocence.

Alice is not a neat “redeemed” mother figure; she remains messy, scared, and grieving. Yet her love for her children becomes her anchor, and her survival is framed as an ongoing struggle against both internal collapse and inherited horror.

Luna

Luna is the novel’s most sensitive receiver of the haunting, and her character blends teenage anger with profound intuitive fear. Her night terrors are not merely dreams; they are the way history reaches a new body that did not consent to carrying it.

The faceless or green-dressed girl in her visions warns her to stay away, positioning Luna as someone being pulled into a story she does not yet understand. At home, Luna is also a daughter confronting her mother’s instability in real time.

Hearing Alice with Jas fractures her trust, intensifying a disgust that is partly moral judgment and partly terror that her mother is slipping beyond her control. Luna’s hostility after nightmares shows a teenager’s attempt to defend herself with rage because vulnerability feels unsafe.

Yet she is not only reactive. As the crisis deepens, she chooses to stand beside Alice, to dig up the buried twin placenta, and to reject the twin’s claim on their family.

Her decapitation of the twin is a moment of brutal coming-of-age: she becomes the one who refuses to let inherited pain define the future. The final scene, where Luna realizes she is pregnant and senses the curse returning, shows her trapped again between agency and inheritance.

She ends as a character facing a terrifying adult threshold, echoing Gigi’s forced motherhood but in a different era, suggesting the fight may not be over even when the monster is.

Luca

Luca represents childhood logic and hope confronted with forces it cannot map. At ten, he is bright, eager, and deeply trusting of systems; his science-fair security project is both cute and symbolic, a child’s attempt to turn fear into something measurable and controllable.

He watches the household’s strange patterns with fascination rather than dread at first, showing how children in chaotic homes often normalize the abnormal. Luca’s discoveries—the breach on his app, the claw marks on the tree, the broken talon—make him the investigator who accidentally confirms the supernatural.

In the climax, his sudden appearance with the machete feels like the purest form of protective love: a child charging into danger because family should be defended. His death is therefore not only tragic but thematically central.

It shows the cost of a curse that feeds on women’s pain but ultimately consumes everyone, and it turns the family’s abstract haunting into irreversible grief. Luca’s absence in the epilogue becomes the new wound the family must carry, mirroring the earlier losses that shaped Gigi and Alice.

Jas

Jas arrives as warmth, playfulness, and escape for Alice, but his character is also marked by a clear desire for stability that Alice cannot meet. The pillow fort scene shows his tenderness and his ability to understand Alice’s lonely inner child; he is not just a lover but a caretaker trying to build a safe emotional space.

His push for commitment is not coercive in intent—he seems to want honesty and integration—but it collides with Alice’s panic and secrecy. Jas’s blunt confrontation about her drinking gives him moral weight; he is one of the few people willing to name her self-destruction directly.

Yet his role is also shaped by what the haunting demands. The twin wants the men Alice loves, and Jas becomes both romantic partner and potential sacrifice.

His presence in the house, his mysterious dragging across the garden in the footage, and his disappearance during the violence position him as a catalyst for the family’s crisis. Jas is therefore a character who embodies the tension between ordinary relationship needs and the extraordinary danger of becoming entangled in someone else’s inherited trauma.

Grant

Grant is defined by frustration, ambition, and a kind of emotional distance that has calcified into impatience. As Alice’s ex-husband and a politician “aiming higher,” he represents public performance and private failure.

His weekend custody and sharp way of speaking to the kids suggest he sees family life as another responsibility to manage rather than a relationship to nurture. Yet the narrative complicates him in the later sections.

His fight with Jas and his brutal beating reveal that, whatever his flaws, he is still part of the family’s gravitational field. His warning that a woman attacked him while trying to get Jas suggests he has glimpsed the supernatural truth, even if he frames it through injury and fear.

After Luca’s death, Grant reunites with Alice in shared grief, indicating that trauma reshapes their relationship more powerfully than resentment ever did. Grant’s character exposes how men in this story can be both disappointing and necessary, both protected and endangered by a curse rooted in women’s suffering.

Judy

Judy functions as the keeper of buried history and the emotional hinge between past and present. As Alice’s mother, she appears first as pragmatic support—dropping groceries, criticizing Grant, trying to keep her daughter afloat—yet her distance in phone calls hints at private burdens.

Her dim sum confession radically recontextualizes the family: she reveals that Alice’s great-grandmother was raped at Nam Koo Terrace, naming the origin of the anger and haunting the women feel without fully understanding. Judy’s admission that she carried twins and lost one before birth introduces the literal mechanism for the double’s return, showing how grief can become physical legacy.

Her choice to bury the placenta under rocks “where nothing ever grew” is thick with symbolism: an attempt to seal away loss that instead nourishes a monster. Judy’s cancer disclosure adds another layer of urgency and mortality; she is a woman running out of time to repair what she hid.

Judy is not villainous for withholding truth—she is frightened, shaped by generations of silence—but her secrecy demonstrates a main idea of The Hunger We Pass Down: what families do not name will still be felt, and often in more destructive forms.

Pinky

Pinky is both outsider and witness, offering a crucial perspective on the family’s unraveling. As a former nanny who still rents the basement suite, she occupies a liminal role—close enough to care deeply, distant enough to see patterns Alice cannot.

Pinky’s Filipino background and her grandmother’s warnings about aswang anchor the supernatural in a cross-cultural vocabulary of monsters that imitate the human, emphasizing that the horror here is not only Chinese-Canadian inheritance but part of a broader diaspora of colonial and wartime violence. Her late-night discovery of Alice’s transformation is one of the story’s most chilling scenes, and her inability to be recognized by Alice in that state underscores how possession erases relational identity.

Pinky’s practical kindness—asking gently about Alice’s drinking, declining wine because she has work—contrasts with Alice’s spiraling suspicion, highlighting how trauma distorts trust. In the climax, Pinky’s injury and continued insistence on staying with Alice and Luna show her courage and loyalty.

She becomes proof that chosen family can stand against inherited terror, even when blood ties are the source of danger.

Old Yan

Old Yan is a figure of worn resilience and quiet moral steadiness amid catastrophe. In the abandoned aftermath of war, she becomes Gigi’s only consistent ally, helping her plan survival not through grand heroism but through practical care—delivering the baby, selling valuables, rationing food.

Old Yan’s presence emphasizes intergenerational female solidarity: she is older, experienced, and unillusioned about how the world treats girls like Gigi. She does not romanticize survival, yet she enables it.

Her discovery of Gigi’s hanging and the baby’s disappearance situates her as another witness to the curse’s cruelty. Old Yan represents the countless older women in wartime histories who carried others through horror with little recognition, and her character adds human warmth to the bleakness of Nam Koo’s legacy.

Auntie (Nam Koo comfort station supervisor)

Auntie embodies a survival strategy that has curdled into complicity. She keeps the girls powdered, groomed, and performing joy for soldiers, suggesting she has learned that obedience can be a shield.

Yet the narrative shows that this “care” is weaponized; she enforces the system that destroys them. Auntie’s disappearance at war’s end feels like an evaporating authority, leaving the girls to face the wreckage alone.

Her character is not drawn as a simple monster but as someone shaped by circumstances that reward cruelty. She illustrates how oppressive systems often rely on intermediaries from within the oppressed group, and how trauma can produce not only victims but enforcers.

Xuan

Xuan offers a foil to Gigi by showing a different response to the same captivity. Where Gigi stiffens and resists, Xuan adapts enough to keep herself alive and future-oriented.

Her departure with an American boyfriend after the war signals her determination to reinvent herself, to outrun the identity Nam Koo tried to stamp onto her. Yet the faceless ghost appearing in Xuan’s green dress suggests that escape is never clean; the mansion’s hunger follows through symbols, dreams, and doubles.

Xuan’s character helps the book explore the moral complexity of survival—how doing what is necessary to live can still leave one haunted.

Bette

Bette is the living consequence of Gigi’s suffering and the vessel through which memory tries to persist. Raised by unrelated caretakers, ignored at home and bullied at school, she grows up marked by stigma—an orphan, a so-called “whore’s daughter,” half Japanese in a society still raw from occupation.

The damaged diary she rereads and the ring of Nam Koo keys she keeps show a girl trying to stitch an identity from fragments left behind. Her haunting is both psychological and literal: dreams of her mother and the clawed hand gripping her palm tie her to Nam Koo whether she wants it or not.

Her marriage to William and emigration to Vancouver continue the pattern of women walking into constrained lives because they lack better choices. Bette’s character is less about individual scenes and more about lineage; she is the bridge that carries the curse into Canada, proving that distance cannot sever inherited trauma.

Through Bette, The Hunger We Pass Down shows how children born from violence are forced to carry narratives they did not author.

William

William appears as the embodiment of domestic entrapment in the diaspora context. Matched with Bette and brought into a life of poverty and tension near a cemetery, he is characterized by anger that fills thin walls.

The book does not dwell on his interior world, which itself is meaningful: he becomes less a fully developed psyche and more a force Bette must endure. His presence demonstrates that the curse’s terrain is not only supernatural but also social—marriage arrangements, financial strain, masculine rage, and the silent expectation that women absorb it.

William’s character thus continues the theme that patriarchal harm is one of the forms the family’s hunger takes.

Tom

Tom is a spectral figure whose main narrative function is to mark the twin’s earliest violence. In Alice’s childhood flashback, he is killed by the monstrous “other daughter,” making him a victim not of war or choice but of hidden inheritance.

His death becomes a buried trauma in Alice’s memory, resurfacing alongside her blackouts. Tom stands for the way childhood loss can be rewritten, forgotten, and then re-experienced later when the family’s history erupts.

Even with limited page presence, he helps connect the twin’s existence to a long arc of feeding on family pain.

Themes

Intergenerational trauma and the way history lives inside families

Nam Koo Terrace is not only a setting but a mechanism for showing how violence can echo forward through bloodlines. Gigi’s adolescent fascination with the mansion begins as longing for safety and beauty, yet the house turns into the site where her childhood ends through wartime sexual slavery.

That catastrophe does not conclude with the war’s end; it is carried into the next generations through silence, gaps in memory, and a persistent sense that something is wrong even when no one can name it. Decades later in Vancouver, Alice’s life is shaped by a haunting that is not supernatural at first glance: her father’s death, the objects he left behind, and the unresolved grief that sits like a weight in the home.

Her blackouts, her inability to keep daily life stable, and Luna’s night terrors all function as symptoms of a buried past. When Judy finally reveals the truth about the comfort station and the family lineage tied to it, the novel frames trauma as something transmitted both biologically and culturally.

The children dream of a place they have never been, using images that belong to their ancestor’s suffering; Alice loses time in ways that mirror the lost time of women whose lives were stolen; and rage keeps resurfacing in the family, as if the body itself remembers what the mind tries to refuse. The “twin” becomes a literal embodiment of this inheritance — a being that feeds on pain, grows stronger with fear, and survives through the hiding of truth.

The final return of the curse in Luna’s pregnancy underscores that trauma does not fade because years pass; it requires confrontation, recognition, and care, or it will take another form. The story insists that historical atrocity is not sealed in textbooks or memorials.

It sits inside kitchens, marriages, parenting, dreams, and bodies, shaping the present until it is faced directly.

Womanhood under coercion, and the struggle for bodily autonomy

Across timelines, the novel shows girlhood and womanhood being controlled by external forces, and it refuses to soften what that control costs. The legend of Nam Koo’s merchant daughter establishes an early pattern: a girl’s future treated as property to be traded for family advancement, with her suicide framed as the only escape left to her.

Gigi’s real experience later expands that pattern into wartime brutality. Her body is not her own within the comfort station, and her resistance is punished until she becomes invisible even in captivity.

Pregnancy follows rape, making her body a terrain on which occupation continues long after soldiers disappear. Yet the narrative also shows how autonomy is complicated by survival choices.

Gigi imagines a life after the war, but her options are narrow and cruel; even the act of naming her child is a brief, fragile claim of agency. In Vancouver, Alice’s autonomy is threatened in subtler but still corrosive ways.

As a single mother tied to exhausting labor, debt, and public judgment, she is trapped inside expectations about what a “good mother” should be. Her sexuality with Jas is both a refuge and a site of vulnerability, because she feels she must hide it from her children and from community scrutiny.

Her drinking becomes another way her body is managed — by her own need to numb and by others’ criticism — and it leaves her uncertain about what she has done, what she has chosen, and what has been taken from her. The twin’s demand for “men in exchange for labor” translates coercion into a grotesque bargain, exposing how women’s work and safety are often tied to appeasing male presence.

Luna’s final pregnancy, touched by the curse, returns the threat to the next young woman’s body before she has had a chance to decide her future. Through these arcs, the novel argues that control over women’s bodies may change costume across eras — marriage deals, military rape, social shame, supernatural blackmail — but the underlying logic persists.

What freedom looks like is never abstract here; it is physical, daily, and fought for under conditions that make simple choice nearly impossible.

Doubling, fractured identity, and the fear of becoming what harmed you

The faceless girl, the ghost who shares Gigi’s face, and the murderous twin in Vancouver form a network of doubles that turn identity into a battlefield. At first the faceless girl appears as a horror image, but her facelessness also signals erased personhood.

She is every girl whose story has been stripped away by patriarchal myth or wartime exploitation. When Gigi later sees that the faceless figure has her own face, the novel pushes the idea further: trauma can split the self.

The double taking Bette is not only a supernatural kidnapping but a representation of how desperate survival can feel like being robbed of one’s own life, or even collaborating in the theft if it is the only way a child might live. The Vancouver twin continues this logic by acting out Alice’s hidden impulses and inherited rage.

She cleans, packs orders, attacks men, and invades the household while Alice sleeps — a nightmare version of the self who “handles everything,” and also the self that carries violent history. Alice’s terror comes from not knowing whether the monster is separate from her or merely her own blackout behavior.

That uncertainty mirrors the way children of trauma often fear what they might become, especially when anger and addiction run in the family. Luna’s dreams intensify this theme: her mother snapping a man’s head off is a child’s vision of parental danger fused with ancestral violence.

What makes the twin especially disturbing is her claim to be part of the family’s natural order, feeding on pain “for generations. ” She is identity made predatory, insisting that suffering defines who these women are.

The struggle against her is therefore not just physical but symbolic: it is a refusal to accept that the family’s story equals misery. Luna’s decision to return and fight alongside her mother marks a choice to own her connection without letting it dictate her fate.

Yet Luca’s death shows how breaking free can still demand unbearable cost, and the curse’s reappearance in Luna’s body suggests the split self is never fully defeated by one act. The theme holds that identity under trauma is unstable: people can feel separated from their actions, haunted by versions of themselves they never asked to carry.

Healing, in this framing, requires naming the double — admitting what history has planted inside you — and still insisting you are more than that inheritance.

Migration, dislocation, and the search for home across continents

The movement from Hong Kong to Vancouver is not presented as a clean transition into safety. Instead, the novel treats migration as another layer in the family’s restless history.

Gigi’s world is defined by war and occupation, where even familiar streets become dangerous and private spaces are seized by foreign power. Her later disappearance and Bette’s orphaned upbringing underline that home can be lost not only through travel but through rupture and theft.

Bette’s emigration to Canada happens through marriage, and her new house beside a cemetery is described as cramped, tense, and filled with William’s anger. The shift therefore does not erase hardship; it rearranges it.

In Vancouver, Alice lives in a home saturated with relics of her father, and that saturation becomes another kind of displacement: she is stuck living inside a past she cannot exit. Her business is online and rootless, her relationships unstable, and her parenting shaped by a life that never feels grounded.

The children’s dreams of Nam Koo, a place they have never physically seen, show that geography does not contain belonging. A family can be shaped by a homeland that exists only as memory, myth, or terror.

Judy’s desire to visit the mansion late in life is similarly complex — not nostalgia, but a need to face what was hidden. The curse crossing oceans makes a clear argument that migration cannot automatically protect descendants from the injuries of origin.

At the same time, the Vancouver setting highlights other forms of alienation: racialized family histories partially erased in diaspora, the pressure to succeed economically in an expensive city, and the loneliness of trying to parent without a stable support system. The novel does not romanticize either place.

Hong Kong carries beauty and brutality; Vancouver carries opportunity and haunting. Home becomes less a location and more a contested emotional space where safety, identity, and memory must be renegotiated.

By the end, even after the house is sold, the family cannot simply “move on,” because home is also the body that carries lineage. Luna’s pregnancy on Galiano Island shows that the search for home continues into new landscapes, but the past travels with you.

The theme suggests that migration is both survival and burden: it offers distance from old wounds but also forces families to carry those wounds into unfamiliar soil, hoping to grow something different while shadows persist.

Motherhood, family bonds, and love shaped by damage

The relationships between mothers and children in the novel are intense, tender, and often broken by forces larger than any individual. Gigi’s mother struggles in poverty after abandonment by her husband, and her volatility shows how economic survival can corrode caregiving without erasing love.

Gigi’s own motherhood arises from violation, and her attachment to Bette is fierce precisely because the child is both an unbearable reminder and a reason to keep living. Her willingness to offer herself so Bette might survive is shown as profound love in conditions that leave no good choice.

Bette’s later upbringing without her mother’s presence becomes another distortion: she carries Gigi’s diary like a lifeline to an absent bond, while enduring stigma that reduces her to the circumstances of her birth. In Vancouver, Alice’s motherhood is defined by exhaustion and fear.

She loves Luna and Luca, but love is constantly strained by debt, overwork, alcohol, and grief. The children experience that strain as instability, secrecy, and emotional whiplash, especially Luna, whose adolescence makes her both perceptive and raw.

Their conflicts are not framed as simple rebellion; they are survival reactions to a home that feels unsafe and unpredictable. Judy’s role complicates the theme further: she provides food and some support, but withholds the family’s central truth until late, leaving Alice and the kids to suffer symptoms without context.

The twin’s presence inside the household twists motherhood into horror, staging a parody of family unity by forcing mother and daughter into a posed “family picture. ” Her demand to take the men Alice loves in exchange for domestic order exposes the cruel bargains women are often pressured into for the sake of keeping a family together.

Luca’s death is the novel’s most brutal statement about the stakes of maternal protection: sometimes even the fiercest love cannot prevent loss when a family is fighting ancestral violence. Yet the bond between Alice and Luna after this loss shifts into something more equal, rooted in shared grief and the decision to face reality together.

The final pages refuse sentimental closure; motherhood remains a site of vulnerability, especially as the curse returns through Luna. Still, the theme insists that love in damaged families is not fake or secondary.

It is powerful, protective, and sometimes the only force that pushes characters to tell the truth, fight back, and try again, even when the past keeps demanding payment.