The Irish Girl Summary, Characters and Themes

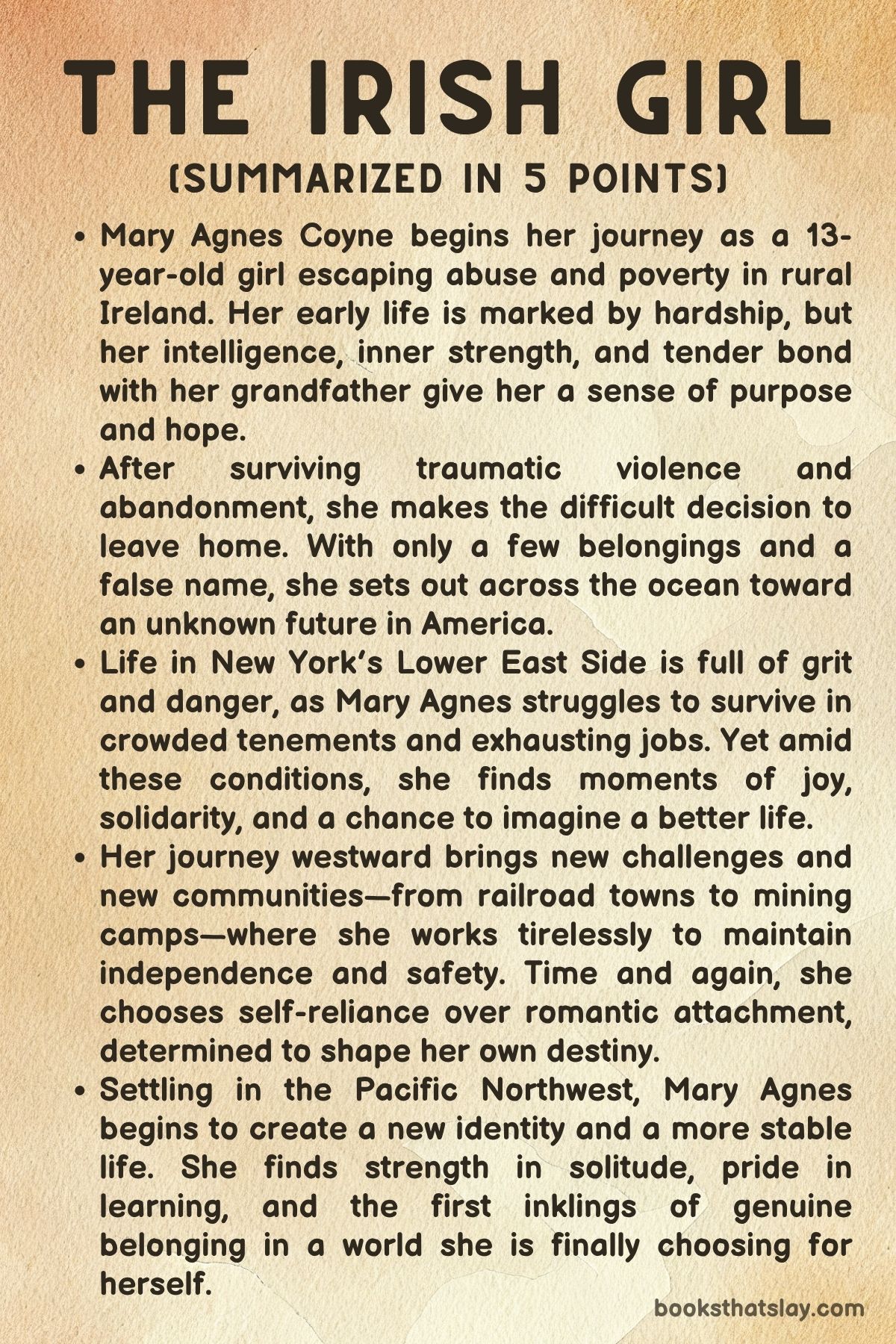

The Irish Girl by Ashley E. Sweeney is a sweeping historical novel that traces the emotional, spiritual, and physical journey of Mary Agnes Coyne, a resilient young girl fleeing violence and poverty in late 19th-century Ireland.

Beginning in Galway and ending in Chicago, with stops in Liverpool, New York, and Colorado, the novel captures the harrowing realities of immigration, the complexities of family betrayal, and the search for identity and belonging. Through lyrical prose and unflinching realism, the book offers an intimate portrait of a teenager grappling with trauma, faith, and survival as she confronts the unfamiliar challenges of the New World while holding tightly to fragments of home.

Summary

At just thirteen years old, Mary Agnes Coyne prepares to leave her small fishing village in rural Ireland in October 1886. Standing at the grimy Galway docks, her patched-together clothes—many made with care by her grandmother—serve as both literal and emotional armor.

She is not departing for America with dreams alone, but out of desperation, especially to escape her abusive half-brother, Fiach. Her grandfather Festus, the only consistently loving adult in her life, gives her a little money and a letter to a church in New York, along with parting words of love that fail to ease her dread.

Five months earlier, Mary Agnes had been fishing with Festus during a violent storm. The sea, though dangerous, is a place of strange comfort and temporary escape from a house defined by hunger, physical abuse, and despair.

At home, her father is cruel and dismissive, her mother embittered and aggressive, and Fiach a constant threat. One night, Fiach assaults her.

When she tries to tell her father, he blames her. Mary Agnes’s internal rage grows alongside her desperation—not only to survive but to prevent herself from becoming her mother, worn down and devoid of hope.

Her salvation arrives in the form of her grandparents’ home. After fleeing to them, Mary Agnes is offered a temporary reprieve from the violence.

Her grandfather arranges for her to be tutored by Seamus Bourke, whose introduction of literature—particularly Yeats’s “The Stolen Child”—stirs something within her. The idea that the world is “more full of weeping than you can understand” speaks to the deep sorrow she already carries.

She also begins to bond with Jonesy, a local boy, and savors the fleeting joy of music, food, and intellectual curiosity.

But the safety is not permanent. Her grandmother Grace reveals that she must emigrate to Chicago due to their failing health and limited resources.

Mary Agnes is torn between her growing sense of self and the fear of leaving her only sources of love. The farewell is emotionally intense.

On her last day, she tries to visit her family and is once again assaulted by Fiach. Her grandmother helps hide her from authorities and the decision to leave becomes a necessity for survival.

Her journey to America is brutal. Onboard the Siren and later the Endeavour, she experiences seasickness, hunger, and even theft from a bunkmate who eventually dies of illness.

Aboard the ship and during stops, she meets people like Jimmy Scanlon, who reflect both the dangers and moments of camaraderie along the immigrant path. At Castle Garden, the immigration processing center, Mary Agnes is stripped of her remaining dignity, forced to undergo dehumanizing treatment.

Yet she clings to faith and to the letter her grandfather entrusted to her.

Arriving in Chicago at fourteen, Mary Agnes becomes a servant for the Rutherford family. At first, she is grateful for a warm bed, food, and a pair of boots.

But her past continues to haunt her. A letter from her mother blames her for Grace’s death and rehashes the shame tied to the assault.

Eventually, gossip by another servant, Doria, leads to her dismissal. She is devastated again when she learns of Festus’s death through another letter.

Her cousin Helen helps her recover and she takes a job with the O’Sullivan family, a more kind and understanding household. Her Sundays are free, wages are fair, and she begins to rebuild her life.

It’s here that she meets Thomas Halligan, a kind young Irishman at church. Their courtship grows slowly and sweetly, culminating in marriage just before her seventeenth birthday.

Although happy, the absence of her grandparents and the severed ties to her family in Ireland cast a shadow on what should be a joyful union.

Their life together in Chicago starts out with humble happiness, but Tom soon begins to show symptoms of tuberculosis. In search of a healthier climate, they relocate to Colorado Springs.

There, Mary Agnes takes on the role of caregiver with strength and grace. Despite the slow decline of Tom’s health, they find beauty in simple moments—dancing, sharing pies, visiting local springs.

When Tom eventually dies, Mary Agnes is devastated but holds her grief with quiet dignity.

She stays in Colorado, working for a kind man named Henry and forming a close friendship with Dutch, a fellow boarder. After Henry’s death, Mary Agnes is offered the chance to join Dutch in Santa Fe but chooses instead to return to Chicago, feeling unready to embrace another unknown.

Back in the city, she returns to work and tries to rebuild. One night, she dances with a man named Rooster Rooney and is assaulted.

The trauma results in pregnancy, and when her condition is discovered at work, she is dismissed. Isolated and ashamed, she moves into a rough neighborhood and miscarries her child alone.

She writes to her estranged family, but her mother refuses contact. Only her brother Sean responds, delivering news of the deaths of their parents and youngest brother.

Her surviving siblings have immigrated to Chicago but want nothing to do with her. Despite overwhelming sorrow, Mary Agnes continues forward, working brutal jobs and scraping by.

A turning point arrives when she helps a pregnant, homeless Doria Rutherford—the same girl who once helped get her fired. Without judgment, Mary Agnes bathes and feeds her, offering dignity and grace.

Doria vanishes the next morning, but leaves $100 as thanks. With that money and new resolve, Mary Agnes writes to Dutch in Santa Fe.

His reply is warm and inviting, telling her about Rancho Vista. Without informing anyone, Mary Agnes packs her satchel—the same one she brought from Ireland—and quietly boards a train to Santa Fe.

Now nineteen, Mary Agnes steps into her future not with certainty, but with a quiet, earned strength. Her journey through abuse, loss, immigration, and love has shaped her into a young woman who understands both suffering and the need for self-determination.

With no guarantees but renewed hope, she chooses once again to move forward.

Characters

Mary Agnes Coyne

Mary Agnes Coyne is the unrelenting heart of The Irish Girl, and her character arc spans a sweeping transformation from a physically and emotionally abused child in rural Ireland to a self-possessed, resilient young woman carving a life in America. Her early life is marked by dire poverty, familial neglect, and sexual violence, particularly at the hands of her half-brother Fiach, which leaves indelible psychological scars.

Despite the brutality she endures, Mary Agnes exhibits an interior richness that blossoms through her connection to poetry, religion, and the sea. Her Catholic imagination, ignited by icons like the Purple Mary, sustains her spirit even as her external world crumbles.

As she journeys from Galway to Liverpool, then to New York, and finally Chicago, she navigates each harsh transition with a remarkable blend of vulnerability and steely will. Her evolving identity as a fisherwoman, student, servant, wife, and widow all contribute to a dynamic portrait of a girl who refuses to be defined by her trauma.

Ultimately, Mary Agnes grows into a woman of quiet power and dignity, shaped by pain but not consumed by it, choosing in the end to forge a life of her own making in Santa Fe.

Festus Coyne (Granda)

Festus Coyne, Mary Agnes’s grandfather, is a beacon of warmth, guidance, and emotional refuge in her otherwise cold and violent early life. His gentleness and humor contrast starkly with the cruelty of Mary Agnes’s immediate family.

He becomes a mentor and protector, taking her fishing and encouraging her dreams beyond the constrictions of poverty and patriarchy. Festus’s storytelling, particularly his fable of the Phantom Isle, provides Mary Agnes with a symbolic vocabulary for courage, hope, and the belief in hidden possibilities.

Even as he grapples with his own limitations, Festus gives Mary Agnes tangible and intangible gifts—money, education through Seamus Bourke, and above all, unconditional love. His death is a profound blow to Mary Agnes, leaving her untethered at a time when she most needs his grounding presence.

Yet, his influence continues to shape her long after, anchoring her moral compass and serving as an enduring source of strength.

Grace Coyne (Grandmother)

Grace is a complex figure who represents both tradition and sacrifice. Her decision to send Mary Agnes to America is born of a terminal illness and a painful recognition of the limitations their Irish home can offer.

Though not as emotionally demonstrative as Festus, Grace’s strength lies in her capacity for action under dire circumstances. She orchestrates Mary Agnes’s escape, shielding her from the Royal Irish Constabulary and providing her with a survival strategy.

Grace’s practicality and foresight ultimately serve as the foundation for Mary Agnes’s chance at freedom. Her death off-page looms large in the narrative, both as a loss and as a legacy, prompting Mary Agnes to reflect on maternal strength that is expressed through difficult choices rather than tenderness.

Fiach Coyne

Fiach is the central embodiment of violent patriarchy in The Irish Girl, and his assault of Mary Agnes catalyzes her entire emigration journey. A predator protected by his family’s silence, Fiach’s character is unredeemed and static, a figure of unchecked male dominance.

His role in the narrative is not simply that of an antagonist but a symbol of the societal and familial rot that forces young women into exile to survive. His repeated violence, combined with the complicity of his parents, exposes the depth of Mary Agnes’s entrapment and the dire consequences of speaking out.

Even after Mary Agnes escapes, the memory and trauma of Fiach’s abuse reverberate through her experiences in America, shaping her relationships and sense of self-worth.

Anna Coyne (Mother)

Anna is a tragic, embittered woman who is both victim and enabler within the toxic family structure. Crushed by poverty and childbirth, Anna becomes emotionally hollow, directing her frustration and helplessness toward Mary Agnes.

Her refusal to believe Mary Agnes’s account of the assault, and later blaming her for familial tragedies, exemplifies internalized misogyny and maternal betrayal. She symbolizes the cyclical nature of abuse and how women, when denied agency or dignity, may perpetuate harm themselves.

Anna’s cold letters from Ireland act as psychological weapons, haunting Mary Agnes long after she’s physically free, and reinforcing the emotional toll of exile and familial rupture.

Seamus Bourke

Seamus Bourke is a key transitional figure in Mary Agnes’s intellectual and emotional development. As her tutor, he introduces her to poetry, particularly Yeats’s “The Stolen Child,” which resonates with her sense of alienation and desire for another world.

Seamus recognizes her intelligence and cultivates her literary gifts, affirming her worth beyond domestic or survivalist labor. His lessons offer Mary Agnes a doorway into beauty and self-expression at a moment when her life is otherwise defined by repression.

Though he exits the narrative early, his influence lingers in Mary Agnes’s poetic musings and aspirations.

Thomas Halligan

Thomas Halligan is the gentle husband whose brief yet profound presence marks a period of love and respite in Mary Agnes’s tumultuous life. Their courtship, rooted in respect and shared cultural ties, offers Mary Agnes her first experience of safe, reciprocal affection.

As a partner, Tom is supportive and tender, qualities that shine especially during his decline from tuberculosis. The couple’s move to Colorado Springs underscores Mary Agnes’s capacity for loyalty and selfless care, even under immense strain.

Tom’s death is not only a personal tragedy but a symbolic rupture of the promise that America might bring lasting stability. His memory becomes a quiet force in Mary Agnes’s ongoing resilience and capacity to love without bitterness.

Dutch

Dutch is a quietly heroic figure who stands by Mary Agnes through multiple phases of her American life. Initially a companion at the Colorado ranch, Dutch’s steadfast loyalty, pragmatic nature, and eventual invitation to Santa Fe provide Mary Agnes with a final lifeline.

He represents an alternative model of masculinity—respectful, generous, and emotionally available. When Mary Agnes chooses to write to Dutch at the end, and later boards a train to join him, it signals not a romantic fantasy but a mature, hopeful redefinition of home and belonging.

Dutch becomes a symbol of renewal and the possibility of a future grounded in trust.

Doria Rutherford

Doria’s trajectory—from the gossiping servant who helped Mary Agnes lose her job in Chicago to a destitute, pregnant woman—mirrors the novel’s theme of precarious womanhood in patriarchal society. Her downfall illustrates how quickly social standing can collapse and how harshly society judges women for sexual transgressions.

Mary Agnes’s decision to help Doria, despite their painful past, reveals her growth into a person guided by compassion rather than resentment. Doria’s final act—sending Mary Agnes money anonymously—underscores mutual redemption and the silent solidarities that can exist between women marginalized by the same structures.

Jimmy Scanlon

Jimmy is a rough-edged but ultimately kind-hearted young man Mary Agnes meets during her journey to America. Though initially gruff and self-serving, he proves protective and resourceful in crucial moments, including fending off predators and helping her navigate immigrant entry points.

Jimmy represents a form of masculine energy that, while not gentle like Tom or Dutch, is still non-exploitative. His presence during her passage helps Mary Agnes sharpen her instincts and assert boundaries, furthering her evolution into someone who can navigate male-dominated environments with cautious self-assurance.

Themes

Female Agency and the Struggle for Autonomy

Mary Agnes Coyne’s journey across continents and class boundaries underscores a constant and painful struggle to assert agency in a world that repeatedly tries to suppress it. From the moment she boards the Siren to Liverpool, her life is no longer governed by the whims of her violent family but by her own will to survive.

This shift, however, is not a clean break—it is shaped by trauma, economic necessity, and the deep psychological scars of abuse. Her decision to leave Ireland, encouraged by her dying grandmother and facilitated by her grandfather, is not one made with naïve optimism but with measured courage.

As a young girl, she is forced to learn quickly that the only person who will consistently act in her best interest is herself.

Her movement through various employments in Chicago—from domestic service to hotel work to labor in the Union Stock Yards—demonstrates the economic and social limitations placed on working-class women. Despite these limitations, Mary Agnes actively shapes her trajectory.

She refuses to become a victim of her circumstances, even after being assaulted, shamed, and shunned. Instead of succumbing to despair, she finds within herself a deep reserve of strength, evidenced by her quiet persistence in the face of cruel gossip, financial instability, and emotional abandonment.

Her final decision to write Dutch and later board a train to Santa Fe is not framed as an act of desperation, but one of reclamation. It is a clear, self-authored step toward building a future of her own choosing.

By the novel’s close, Mary Agnes is not simply a survivor of misfortune but an architect of her life, shaped by hardship but no longer controlled by it.

Trauma and Survival

The narrative of The Irish Girl is punctuated by acts of violence and betrayal that leave enduring imprints on Mary Agnes’s psyche. From the assault by her half-brother Fiach to the cold dismissal by her mother, the initial phase of her life is one marked by deep familial harm.

These traumas are compounded by the hostile conditions she encounters during her immigration voyage and in the United States, including an attempted assault at Castle Garden and another by Rooster Rooney in Chicago. Each experience intensifies her vulnerability, particularly as a young immigrant woman with little institutional or familial protection.

Yet, the novel does not frame Mary Agnes’s identity solely through the lens of victimhood. Instead, it presents a nuanced depiction of survival—one that incorporates not just endurance but the careful preservation of hope, dignity, and empathy.

Her internal world, rich with poetry and spiritual imagery, becomes a sanctuary that helps her make meaning of her pain. Even in the aftermath of miscarriage and abandonment, Mary Agnes finds it within herself to care for others, such as when she bathes and comforts the disgraced Doria Rutherford.

This moment encapsulates the emotional maturity that trauma has forged within her: she recognizes suffering in others and meets it with compassion rather than judgment.

Mary Agnes’s survival is not portrayed as a miraculous triumph but as a day-by-day commitment to continue. Her suffering is not erased, nor is her resilience romanticized.

Instead, her capacity to keep going—through death, exile, assault, and rejection—is presented as a quiet, unflinching kind of heroism. Her survival becomes an act of resistance against all the systems and individuals who attempted to erase her agency and worth.

The Immigrant Experience and the Myth of the American Dream

Mary Agnes’s journey across the Atlantic encapsulates the contradictions at the heart of the immigrant experience in the late 19th century. Her arrival in America is not heralded with opportunity and welcome but with lice removal, invasive inspections, hunger, and death.

The death of Mary Catherine, her bunkmate on the ship, underscores the fragility of survival during these voyages, especially for unaccompanied young girls. Far from being a land of freedom and prosperity, America proves to be a terrain of continuous tests—physical, emotional, and moral.

Employment in Chicago brings some respite but also reveals a class-based system where Irish immigrants, especially women, are relegated to domestic labor and vulnerable to exploitation. The Rutherford household, the Tremont House, and the Union Stock Yards all represent microcosms of the broader society: stratified, suspicious, and unforgiving to the powerless.

Still, within these spaces, Mary Agnes navigates her position with ingenuity and resolve. Her gradual rise—from fired servant girl to hotel worker to someone choosing her future destination—reflects not a straightforward ascent, but an iterative process of adaptation and negotiation.

The American Dream is exposed not as a universal truth but as a selective reality available to those who can endure the cost. For Mary Agnes, the dream does not come in the form of wealth or fame but in the opportunity to choose, to start over, and to claim a life free from the shadows of her past.

By choosing to board the train to Santa Fe, she defines the American promise on her own terms—not as something handed to her, but as something earned through pain, sacrifice, and self-determination.

Love, Loss, and the Complexity of Belonging

Throughout The Irish Girl, Mary Agnes is repeatedly forced to navigate the fragile contours of love and the wrenching realities of loss. Her earliest expressions of love—for her grandparents, her brother Tommy, and her tutor Seamus—are rich with emotional depth but are also laced with impermanence.

These figures offer safety, validation, and affection, yet they are inevitably lost to time, death, or separation. Her marriage to Thomas Halligan represents a peak of emotional fulfillment, with their life in Colorado Springs marked by tenderness, domestic joy, and mutual respect.

But even this love is transient. Tom’s slow death from tuberculosis and Mary Agnes’s role as caregiver foreground the cruel temporality that shadows even the most sincere attachments.

The loss of her child following Rooster Rooney’s assault furthers this motif of grief and erasure. She is not only mourning a potential life but also the part of herself that dared to believe in a future free of shame and violence.

Yet, despite the magnitude of her losses, Mary Agnes never detaches from the human need to connect. She continues to form bonds—however fragile—with those she meets, such as Dutch, Helen, and Doria.

Belonging remains elusive. Rejected by her family in Ireland, cut adrift in American cities, and repeatedly forced to uproot herself, Mary Agnes redefines belonging as something not bound to a location or kinship but forged through values, memory, and chosen relationships.

Her love is not destroyed by loss; it becomes more discerning, more deliberate. As she boards the train to Santa Fe, she does so with no guarantees but a clear sense of what kind of life and love she deserves.

Faith, Storytelling, and the Power of Inner Worlds

The religious and imaginative life of Mary Agnes offers a vital counterbalance to the external brutality of her world. Her Catholic faith, passed down by her grandmother and nurtured through ritual, images like Purple Mary, and the liturgy of Mass, becomes both a source of comfort and a means of interpreting her experiences.

At moments of despair, she turns not just to prayer but to poetry, particularly Yeats’s “The Stolen Child,” whose melancholic refrain mirrors her feelings of alienation and longing. These spiritual and literary influences are not simply decorative—they shape how she understands suffering, beauty, and purpose.

Her relationship with storytelling, inherited from Granda Festus and enriched through her studies with Seamus, empowers her to see beyond her immediate pain. Stories like the Phantom Isle are not mere fantasies; they become symbolic anchors, tools for survival, and maps for reinvention.

Even her silent, private recitations during the worst moments of her journey reveal how imagination and memory can fortify the self when the world seeks to dismantle it.

Rather than escape into these inner worlds, Mary Agnes uses them as fuel for her real-world decisions. Faith and storytelling are not mechanisms of denial but strategies of endurance.

They allow her to hold on to her identity, even when she is stripped of possessions, family, and place. By the novel’s end, it is this inner life—nurtured through belief, art, and memory—that sustains her as she chooses a new path forward, not just geographically but existentially.