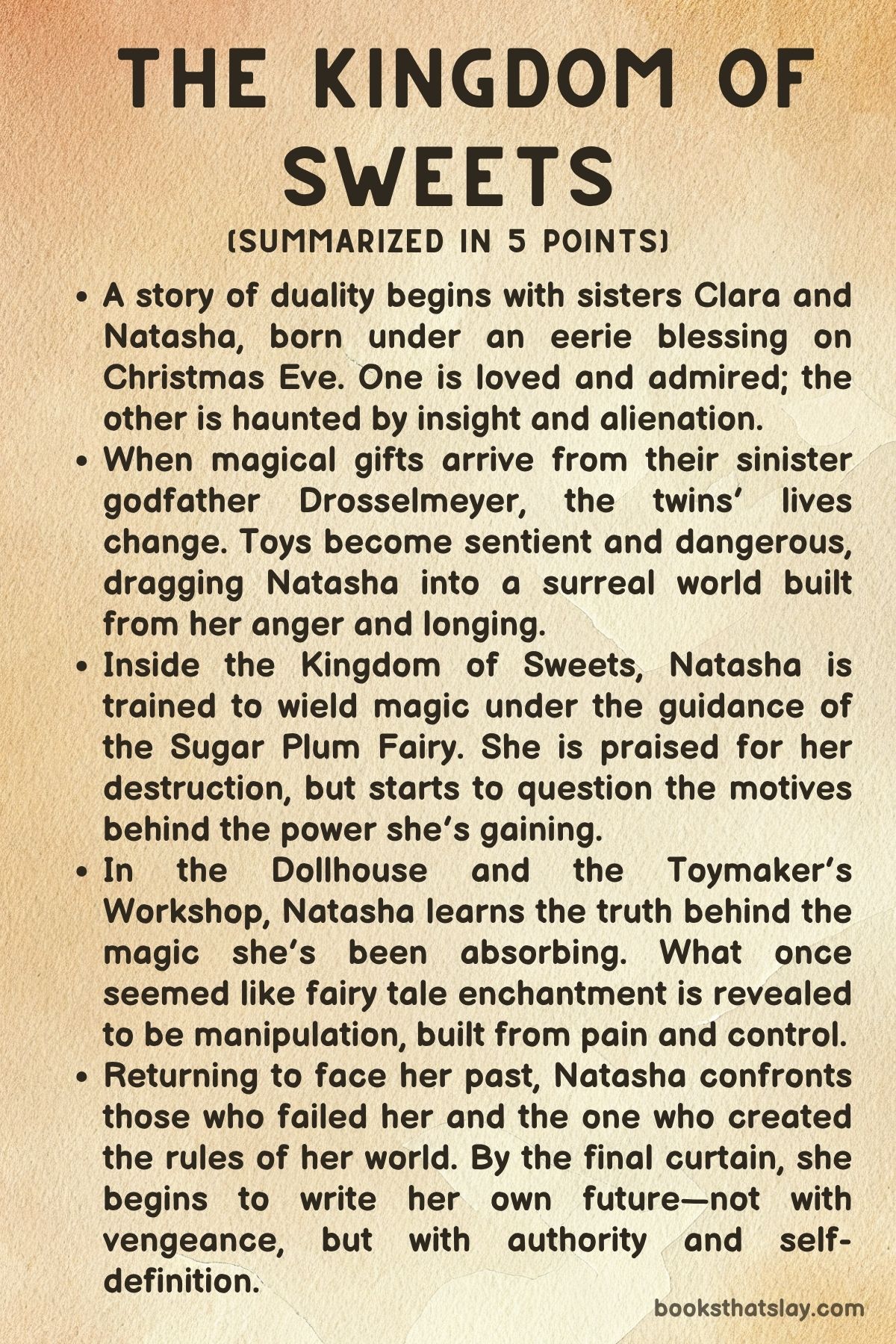

The Kingdom of Sweets Summary, Characters and Themes

The Kingdom of Sweets by Erika Johansen is a dark and emotionally charged reimagining of the Nutcracker story. It transforms a beloved holiday fairy tale into a sharp exploration of power, grief, and identity.

At the heart of the novel are twin sisters Clara and Natasha, whose fates diverge under the influence of magic and betrayal. The narrative uses its fantastical setting not to escape reality but to scrutinize it.

It examines how trauma is inherited, how stories shape identity, and how young women navigate a world determined to control them. Rich with symbolism, it offers both a fantasy adventure and a psychological reckoning.

Summary

Natasha and Clara Stahlbaum are born on Christmas Day into a wealthy, crumbling household that appears polished but hides deep rot. Clara is golden and adored, gifted with beauty and ease.

Natasha is her opposite—introspective, brooding, and marked from birth with a darker magic. Their godfather, Drosselmeyer, casts an eerie influence from the moment of their christening, offering Clara the blessing of light and Natasha the burden of insight.

On their seventeenth birthday, he returns with enchanted gifts: a nutcracker for Clara and a grotesque clown for Natasha. That night, Natasha watches the barriers between reality and nightmare break down, as magic surges and toys come alive.

She also discovers Clara is secretly engaged to Conrad, the boy Natasha quietly loved. Betrayed by both her sister and her family, Natasha clutches the nutcracker and disappears into another world.

She awakens in the Kingdom of Sweets—a surreal, deadly realm where enchantment masks cruelty. Here, the Sugar Plum Fairy reigns with a chilling mix of elegance and manipulation.

She grooms Natasha to become a magical warrior, exploiting her rage and grief. Natasha is trained in magical combat and subjected to trials that celebrate violence and obedience.

Candy-coated illusions distract from the pain beneath. The Fairy entices her with praise, magical wine, and increasing power, but Natasha begins to sense the hollowness of these rewards.

She connects with Petra, a mute and scarred girl who survived previous horrors in the kingdom. Their quiet bond anchors Natasha’s humanity as she struggles to hold onto herself.

As Natasha adapts, she learns to perform the role expected of her, especially during her time in the Dollhouse—a symbolic prison where girls are molded into idealized, decorative objects. She’s dressed, posed, and mentally manipulated, all under the guise of femininity and perfection.

But Natasha resists. She senses that these performances are designed to erase her, and in a key moment of rebellion, she breaks the spell in front of an enchanted audience.

The Nutcracker, once a mechanical protector, becomes more human as he responds to Natasha’s awakening. He begins to remember his own past—hints of suffering, loyalty, and entrapment.

Natasha is then taken to the Toymaker’s Workshop, the origin point of all the magic in the realm. Here, she witnesses how toys are not made but cursed—how souls are bound, memories rewritten, and obedience manufactured.

The Toymaker is Drosselmeyer in another form or a fragment of his will. Natasha realizes that her pain, and others’, has always been scripted for spectacle.

Petra nearly dies in another magical test, pushing Natasha into action. She uses the Toymaker’s tools to create freely, without control, and breaks spells thought to be permanent.

By seizing the power of creation, she declares her rebellion. The final confrontation takes place as Natasha returns to her world.

She finds Clara burdened with guilt and no longer enchanted by privilege. Conrad is exposed as weak and unwilling to face truth.

Natasha breaks the illusion cast over her city, exposing Drosselmeyer’s manipulations. She does not kill him, but surpasses him.

The Nutcracker, now fully human, chooses to stand with her as an equal. Together, they reject revenge and instead seek a new way forward.

In the closing chapters, Natasha claims authorship of her own story. Clara chooses service over spectacle.

The Nutcracker departs to live a life of his own choosing. Natasha, alongside Petra, stays behind to rebuild—not the magical world as it was, but something new.

The book ends not with a fairy tale’s closure, but with a quiet, radical act: the beginning of a future Natasha will write herself.

Characters

Natasha Stahlbaum

Natasha is the central protagonist of The Kingdom of Sweets, and her journey forms the emotional, psychological, and thematic core of the novel. From the outset, she is marked as the “dark twin”—cursed by Drosselmeyer to perceive painful truths that others cannot or will not see.

Her deep introspection, social alienation, and unrequited love for Conrad set the stage for a gradual unraveling of her psyche and identity. Natasha begins as a young woman haunted by betrayal—most notably by her twin Clara and by the societal structures that worship beauty and obedience while punishing intellect and dissent.

Her passage through the magical world transforms her from a brooding, wounded observer into a fierce author of her own story. This transformation is not linear; it is fraught with temptation, moral confusion, and moments of genuine loss.

In the Kingdom of Sweets, Natasha is subjected to both brutal trials and seductive rewards—her pain is weaponized, and her power is nurtured under the manipulative tutelage of the Sugar Plum Fairy. However, Natasha ultimately transcends this training.

She begins to question not just her tormentors but the very framework of the story she’s been placed within. By the end of the novel, Natasha becomes a figure of mythic significance—not merely as a rebel or sorceress, but as a creator.

She reclaims the act of storytelling itself. Her rejection of vengeance for authorship marks her as a complex heroine—flawed, angry, wise, and finally, free.

Clara Stahlbaum

Clara, Natasha’s twin, is a fascinating foil—an embodiment of privilege, beauty, and performative innocence. On the surface, she appears to be the favored child: beloved by her family, admired by society, and effortlessly charming.

But as the novel progresses, Clara’s role is revealed to be far more tragic and complicit. She benefits from Drosselmeyer’s so-called blessing, living a life shielded from the emotional and spiritual darkness that Natasha must confront.

However, Clara is not simply a villain or a passive object of jealousy. Her silence about her engagement to Conrad and her eventual admission of betrayal reveal a deeper conflict.

Clara has chosen comfort over truth, survival over solidarity. She, too, is a victim—one who internalized the values of a society that commodifies femininity and demands obedience from women.

In the final acts, Clara’s trajectory takes a turn toward humility and healing. She sheds her illusions and chooses a path of service and atonement rather than glamor or power.

Her reconciliation with Natasha is fragile and incomplete, but it offers a nuanced depiction of sisterhood torn apart by societal forces. It is slowly, painfully mended through mutual recognition of suffering.

Clara’s transformation is quieter than Natasha’s but equally significant. She evolves from a symbol of unthinking complicity into a conscious participant in change.

Drosselmeyer

Drosselmeyer is the enigmatic and malevolent architect of the world Natasha must navigate. As godfather to the twins and the originator of the Kingdom of Sweets, he represents not merely a figure of magical power but a patriarchal force that constructs and manipulates reality.

From the very beginning, he imposes opposing destinies on the sisters, reducing their lives to a dichotomy of light and dark, good and evil. Yet Drosselmeyer is far more than a simple villain—he is a dramatist, a toymaker, and a myth-maker who believes in the sanctity of control.

His magical world is a theatre, and the people within it are characters in his grand narrative. He manipulates memory, rewrites history, and uses enchantment to enforce obedience.

Despite his immense power, Drosselmeyer is ultimately undone not through brute force but through narrative subversion. Natasha refuses to play his game by the rules.

In doing so, she reveals the hollowness of his authority. He is not killed or destroyed but rendered irrelevant—a relic of a story that no longer holds meaning.

His lingering presence at the end of the novel serves as a cautionary echo. He is a reminder of the seductive nature of control and the necessity of creative defiance.

The Sugar Plum Fairy

The Sugar Plum Fairy is a complex antagonist and mentor figure—an agent of Drosselmeyer who carries out his vision through manipulation disguised as empowerment. At first, she appears regal and benevolent, offering Natasha power in exchange for obedience.

She trains Natasha to weaponize her emotions, especially rage and grief, converting them into tools of destruction and spectacle. But her guidance is laced with cruelty.

She glamours suffering, encourages brutality, and enforces conformity under the guise of artistry. She presides over performances that demand submission, especially from girls.

She uses charm to veil the violent control she exercises. As Natasha begins to resist, the Fairy’s elegance falters, revealing a zealot committed not to justice or even order, but to spectacle and dominance.

Her greatest tragedy lies in her belief that she is liberating Natasha when she is, in fact, crafting another puppet. When Natasha disrupts the script, the Fairy is revealed as complicit in a cycle of oppression she claims to transcend.

Though powerful, she is ultimately a servant to a greater manipulator. Her fall marks the disintegration of illusion as the dominant force in the kingdom.

Petra

Petra is one of the most poignant and symbolic characters in the novel. A silent survivor of the Fairy’s earlier games, Petra embodies the costs of resistance and the trauma of transformation.

She is not merely a background figure; she is a mirror to Natasha—an image of what could happen when one surrenders too much, too soon. Her muteness, scarred body, and unwavering loyalty serve as living testimony to the abuse embedded in Drosselmeyer’s magical regime.

Despite her suffering, Petra remains resilient. Her relationship with Natasha evolves into a quiet sisterhood based on shared pain and mutual recognition.

Her near-death in the workshop jolts Natasha into decisive rebellion, functioning as both a sacrifice and a catalyst. Petra’s presence in the final scenes—surviving, healing, and staying with Natasha—symbolizes hope and the possibility of reimagining community beyond domination.

She is not a warrior or a ruler, but a survivor. In this tale of spectacle and power, survival becomes its own form of resistance.

The Nutcracker

The Nutcracker, first introduced as a magical toy gifted to Clara, emerges as a deeply tragic and ultimately redemptive character. Initially voiceless and mechanical, he gradually reveals a tortured humanity beneath his enchanted surface.

Bound by Drosselmeyer’s magic, he represents the theme of enslavement disguised as loyalty. His transformation mirrors Natasha’s: both begin as pawns, both endure manipulation, and both must awaken to their own agency.

As Natasha’s protector, the Nutcracker is enigmatic, sometimes uncanny, and later profoundly moving—especially as he begins to express emotion, bleed, and remember his origins. He is revealed to be a creation of Mikhail, born out of pain and defiance.

By the end of the novel, he is no longer a tool but a person with choices. His decision to leave Natasha—not out of abandonment but to seek his own story—represents one of the novel’s most touching departures from traditional fairytale endings.

The Nutcracker does not get the girl or the crown. He gets freedom.

Mikhail

Mikhail is an elusive, scarred boy who initially appears as a minor character but slowly emerges as a key to the Kingdom’s secrets. His past is deeply intertwined with the magical system—he was once like the Nutcracker, a boy broken and repurposed by Drosselmeyer.

Unlike the others, Mikhail retains fragments of memory and will, allowing him to become a quiet subversive within the enchanted world. He is not a mentor or a hero in the conventional sense but a deeply damaged witness who aids Natasha by sharing forbidden truths.

Mikhail’s suffering, ingenuity, and resilience allow him to forge an act of creation in building the Nutcracker, an act of rebellion disguised as service. He does not seek power, and his importance lies not in dramatic action but in the invisible labor of resistance.

His presence is a reminder that even in total systems of control, memory and love can survive. They remain buried but enduring.

Themes

The Burden of Female Identity and the Performance of Femininity

The Kingdom of Sweets deals with the oppressive burden placed on female identity and the violent, often surreal performance of femininity. From the opening chapters, Natasha is cast as the “dark twin,” weighed down not only by a literal magical curse but also by societal expectations that demand submission, beauty, and charm—qualities her sister Clara embodies with ease.

The dichotomy between Clara and Natasha is not merely aesthetic; it reflects a larger commentary on how girls are divided and categorized based on their adherence to social norms of desirability and docility. As the story moves through magical realms like the Kingdom of Sweets and the Dollhouse, these expectations take grotesque physical form.

The Dollhouse, in particular, serves as a brutal allegory for the commodification of girlhood: a place where girls are dressed, posed, and silenced to become pleasing objects. The mute “dolls” lining the walls are not just background figures but cautionary examples—those who failed to meet impossible standards and paid with their voices, agency, and even their lives.

Natasha’s journey becomes a resistance to these roles, but it is not without cost. She is forced to enact the very performances she detests before she can begin to subvert them.

By the final act, the theme reaches its conclusion as Natasha reclaims her narrative, not by shedding femininity, but by redefining it on her own terms. She rejects the binary of angelic versus monstrous femininity and instead claims a new identity that includes power, pain, and freedom without apology or performance.

Power, Control, and the Architecture of Manipulation

The novel meticulously explores how power operates—subtly and overtly—through manipulation, memory, and narrative control. Drosselmeyer, as both a literal and symbolic toymaker, epitomizes the godlike figure who dictates reality through magical and psychological influence.

From Natasha’s christening to the machinations of the Sugar Plum Fairy, we see how systems of power craft identities not by force alone, but through stories, enchantments, and expectations that are internalized by their subjects. The Toymaker’s workshop illustrates this theme most starkly.

It is not merely a place of creation but of reprogramming, where souls are bound into objects, memories are rewritten, and dissent is surgically removed. Natasha’s realization that she has been manipulated for most of her life—that even her deepest griefs and desires have been used as tools to shape her—marks a crucial turning point in the story.

Her rebellion, then, is not just magical but epistemological; she seeks to uncover and reclaim the truth of her own mind. The theme culminates in the public performance Natasha disrupts in Act V, where she exposes the theatricality of control itself.

Drosselmeyer’s empire is not upheld by strength but by the stories people believe about who holds power and why. Natasha’s final rejection of his authority is not a coup but a refusal to participate in the script.

Her authorship of her own story at the end represents a radical act of liberation, where power becomes not a system to inherit, but a structure to dismantle and rebuild.

Grief, Betrayal, and Emotional Transformation

At the emotional heart of the novel lies a profound exploration of grief and betrayal—not only in the interpersonal sense but also as existential forces that shape identity. Natasha’s arc begins with her anguish over Clara’s engagement to Conrad, a romantic betrayal that becomes a symbolic rupture of trust between sisters, between past and future, between illusion and reality.

But the novel refuses to contain Natasha’s pain within a single relationship. As she traverses the Kingdom of Sweets, she is forced to confront the layered betrayals of her family, society, and even her own mind.

Drosselmeyer’s manipulations make her question which memories are real and whether her feelings have any legitimacy. Her training under the Sugar Plum Fairy weaponizes this grief, converting emotional pain into destructive magical ability.

But instead of being consumed by rage, Natasha eventually reshapes her suffering into something more potent: clarity. Petra’s near-death and the Nutcracker’s awakening deepen her empathy, reminding her that vengeance without connection is hollow.

By the end, Natasha no longer seeks retribution but transformation. She understands that healing does not mean forgetting pain but absorbing it into a new vision of power and purpose.

The theme is resolved not through catharsis but through creation—Natasha writes her story not to erase grief, but to frame it as the crucible from which her strength was forged.

The Subversion of Fairy Tale and Myth

Erika Johansen uses The Kingdom of Sweets as a pointed subversion of traditional fairy tale motifs, particularly those found in the original Nutcracker story. Rather than a whimsical fantasy about love and transformation, this narrative critiques the very genre it inhabits.

The magical kingdom is not a place of joy but a battleground of illusions where delight masks cruelty, and sugar-coated aesthetics conceal violence and control. The Sugar Plum Fairy, typically a benevolent figure, becomes an architect of cruelty and conformity.

The Nutcracker, often a dashing hero, begins as a mute, mechanical being who must rediscover his humanity through pain and love. Even the idea of “happily ever after” is dismantled by the final chapters.

Johansen does not offer neat resolutions or fairy-tale rewards. Instead, she presents an ambiguous, open-ended liberation in which Natasha gains not comfort but authorship.

This subversion is not cynical—it is emancipatory. By stripping the fantasy of its comforting illusions, the novel reveals the deeper truths about trauma, identity, and the price of freedom.

Natasha’s final act of rewriting her story becomes a meta-commentary on the nature of narrative itself: who gets to tell stories, whose voices are silenced, and how the act of storytelling can be either a cage or a key. In this way, The Kingdom of Sweets is less a fantasy than a reclamation—a myth rewritten from the inside out.

Memory, Identity, and the Fluidity of Truth

Throughout the novel, memory is not portrayed as a fixed archive of events but as a contested terrain where identity is constantly negotiated. From Natasha’s initial doubts about her past to the Toymaker’s revelation that memories can be implanted, erased, and distorted, the novel suggests that who we are is shaped as much by what we remember as by what we forget.

Drosselmeyer’s control over magical memory is one of his most insidious powers; he rewrites the past not merely to deceive, but to construct a self-serving reality where resistance becomes unthinkable. Natasha’s challenge, then, is not only to remember correctly but to remember ethically.

She must reclaim the narrative of her life without succumbing to the seductive lies of vengeance or victimhood. This theme becomes especially poignant in the scenes where Natasha reencounters altered memories of her childhood or realizes that some of her beliefs about her family and past have been manipulated.

Her final strength lies in her ability to hold onto ambiguity. She recognizes that truth is rarely pure, and memory is always fragile.

By embracing this complexity, she refuses both the fantasy of the innocent girl and the simplification of the avenging witch. In the closing scenes, writing becomes her method of stabilizing identity—transforming mutable memory into chosen story.

But even this act is framed not as finality, but as a beginning. Identity, like story, is never finished—only continually revised with new clarity and choice.