The Labors of Hercules Beal Summary, Characters and Themes

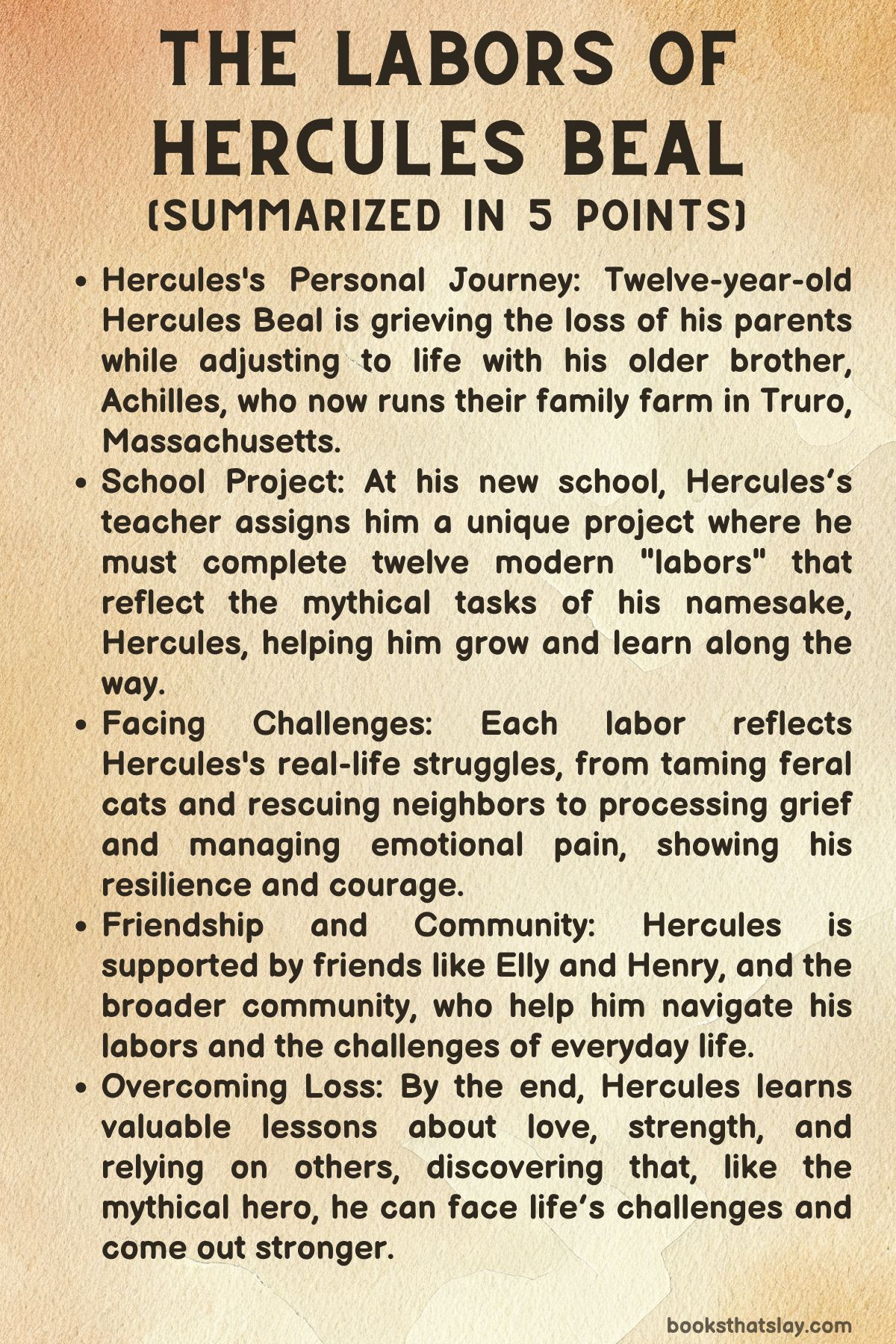

The Labors of Hercules Beal by Gary D. Schmidt is a heartwarming middle-grade novel that follows 12-year-old Hercules Beal as he embarks on a personal journey to complete his own version of the mythic twelve labors for a school project. As Hercules navigates life after the tragic loss of his parents, he draws strength and wisdom from his community, family, and the tasks he tackles.

Set in the picturesque town of Truro, Massachusetts, this coming-of-age story blends themes of grief, resilience, and friendship, showing how small acts of courage help us face life’s hardest moments.

Summary

Hercules Beal is a twelve-year-old boy living in the tranquil town of Truro, Massachusetts. The loss of his parents a year ago has left him in the care of his older brother, Achilles, who now runs their family’s farm.

Starting at the Cape Cod Academy for Environmental Sciences, Hercules faces the typical worries of a seventh-grader, but his world shifts when his new teacher, Lieutenant Colonel Hupfer, assigns him a daunting project: recreate the twelve labors of his namesake, the Greek hero Hercules, in modern life.

Hercules begins his first “labor” when a local one-eyed cat leads him to an abandoned house filled with feral cats.

With help from his friends Elly, Henry, and Ty, he eventually tames the chaos and adopts the cat he names Pirate. His next task mirrors the Hydra’s many heads; Hercules has to gather nine different plant species for a school project, but it brings back painful memories of his father’s hospital machines during his final days.

As he completes the task, he reflects on loss and love, realizing that his parents’ presence still hums in the background of his life.

The third labor, based on capturing the Ceryneian Deer, takes a creative twist as Hercules and his friends decide to paint a tree’s leaves gold to impress tourists. Their plan literally falls apart when rain washes the paint away, leaving them to face the consequences—but a lesson is learned about letting nature run its course.

Next, when a storm traps an elderly neighbor, Hercules recalls the Erymanthian Boar labor, helping to rescue her from the debris and reflecting on how quickly life can shift from safety to danger.

The pressure intensifies with the fifth labor, which sees Hercules tasked with helping move his entire school to the farm after storm damage. Drawing parallels to cleaning the Augean Stables, Hercules organizes volunteers and learns the importance of teamwork.

As the holidays approach, the sixth labor challenges him emotionally, especially after a fight with Ty. He comes to understand that managing his anger and grief is as crucial as overcoming any mythical challenge.

Later, a scare involving his injured dog, Mindy, pushes Hercules to seek help from a reclusive neighbor, reminding him of the seventh labor’s wild bull. By showing compassion, Hercules discovers that people, like animals, can change with kindness.

Throughout the year, Hercules continues facing challenges that echo the labors of his mythical namesake, from dealing with local coyotes to protecting a beloved sculpture from being sold at auction.

When his brother’s relationship falls apart, Hercules feels like his world is crumbling. But in true heroic fashion, he learns to rely on the strength of others, whether it’s his teacher giving him a medal for resilience or his community coming together to help him deliver hundreds of trees.

The final challenge comes when Achilles is in a car accident, and Hercules finds himself in a familiar hospital setting. This time, however, he’s no longer alone—he has the support of friends, teachers, and his community.

By the end of his year-long project, Hercules realizes that life, like the mythical labors, is full of trials, but with courage and help from others, he can navigate even the hardest challenges.

Characters

Hercules Beal

Hercules, the protagonist of The Labors of Hercules Beal, is a 12-year-old boy grappling with the tragic loss of his parents while embarking on a journey of self-discovery. His character reflects resilience, vulnerability, and an evolving sense of maturity.

At the start of the novel, he is emotionally wounded and struggling to navigate life without his parents. His involvement in the school project, where he mirrors the 12 labors of his mythical namesake, helps him gradually come to terms with his grief.

Hercules is resourceful, as seen when he interprets and tackles the tasks presented to him. His deep love for his hometown of Truro, Massachusetts, along with his attachment to nature and the people around him, grounds him as he moves forward in life.

His reflections on the tasks and the relationships he builds or repairs showcase his growing emotional intelligence. Each labor becomes a metaphor for his personal struggles, helping him face his fears, especially regarding loss and responsibility.

Hercules’s journey throughout the novel is both an external and internal adventure. He learns that life, although difficult, is manageable when one leans on others.

Achilles Beal

Achilles, Hercules’s older brother, assumes the responsibility of looking after both Hercules and the family business after their parents’ death. He is depicted as a strong, yet emotionally complex character, burdened with adult responsibilities while managing his own grief.

Achilles’s relationship with Hercules is one of love and care but also marked by tension as they cope with their shared loss in different ways. Achilles’s protective nature shines through, but he also struggles with his own vulnerabilities, particularly his breakup with Viola.

By the end of the novel, Achilles grows emotionally, realizing the importance of family and connection. His injury in the car accident allows Hercules to step up in a new way, mirroring the challenges faced by the mythical Achilles.

Achilles’s character arc reflects themes of responsibility, sibling bonds, and recovery. His journey shows that even the strongest figures need support.

Lieutenant Colonel Hupfer

Lieutenant Colonel Hupfer, Hercules’s humanities teacher, is a strict, no-nonsense figure. His military background informs his demanding teaching style, but beneath his gruff exterior lies a mentor who genuinely cares about his students’ growth.

Hupfer’s role in Hercules’s life extends beyond that of a teacher. He becomes a father figure, guiding Hercules through both the project and life’s hardships.

His wisdom and toughness help Hercules develop a deeper understanding of himself and the world around him. Hupfer’s gift of his military medal to Hercules symbolizes his recognition of the boy’s resilience and strength.

His character is a testament to the importance of mentorship. He plays a significant role in shaping Hercules’s journey of personal growth.

Elly

Elly, Hercules’s best friend, is a steady source of support throughout the novel. She provides guidance and companionship as Hercules works through his labors, often encouraging him to see situations from a different perspective.

For example, her suggestion that the task of capturing the Ceryneian Deer might involve the pursuit of beauty leads to the idea of painting the tree’s leaves. Her temporary absence when she leaves for Ohio adds a layer of emotional complexity, as Hercules must cope with her departure.

Despite this, their eventual reunion solidifies their enduring friendship. Elly’s role highlights the importance of friendship and emotional support in the face of loss and change.

Ty Malcolm

Ty Malcolm is one of Hercules’s classmates who becomes an important part of his circle, though their relationship begins with conflict. At one point, Ty refers to Hercules as an orphan, leading to a physical altercation between the two.

This moment of conflict is significant, as it shows Hercules grappling with his grief and anger. Ty’s character serves as a catalyst for Hercules to reflect on how he handles his emotions and learn the importance of not acting out of anger.

Ty, like Henry, helps Hercules with several of his labors. His character helps illustrate themes of forgiveness, emotional growth, and the complexity of adolescent relationships.

Henry Sugimoto

Henry, another of Hercules’s classmates, plays a significant role in helping Hercules complete his labors. He is imaginative and practical, often providing clever solutions to the problems Hercules faces.

For instance, his suggestion that the elusive Ceryneian Deer might be akin to tourists searching for perfect autumn foliage sparks the idea for the kids to paint the leaves. Henry’s character represents creative problem-solving and the power of teamwork.

His friendship with Hercules demonstrates that even school projects can have profound impacts on personal growth. Henry exemplifies the importance of community and collaboration in overcoming challenges.

Viola

Viola is Achilles’s girlfriend for much of the novel. Her presence in Hercules’s life provides him with a maternal figure after the death of his parents.

Viola is nurturing and kind, often helping Hercules with his school tasks, such as taking him to Cleveland to gather the nine plants for his second labor. Her eventual breakup with Achilles destabilizes Hercules’s sense of family, bringing forth his fear of further loss.

Despite their breakup, Viola remains an important figure in Hercules’s life. Her continued presence symbolizes that familial bonds can transcend romantic relationships, embodying the themes of loss, recovery, and human connection.

Mr. and Mrs. Neal

Mr. and Mrs. Neal are Hercules’s neighbors who play key roles in his life. Mrs. Neal, trapped under her collapsed house during a storm, becomes the subject of one of Hercules’s labors, showcasing his bravery and determination to help those in need.

Mr. Neal’s yelling reminds Hercules of his traumatic memories, yet the Neals also symbolize the support network that surrounds Hercules. Their involvement highlights the importance of community in overcoming grief and adversity.

Mrs. Savage

Mrs. Savage is another neighbor who imparts wisdom to Hercules, encouraging him to see things in the “right light.” Her character represents the importance of perspective and patience, two lessons Hercules learns through his experiences.

When she has to sell her sculptures, including the hippo replica of her husband, her struggle becomes part of Hercules’s ninth labor. Helping her recover the hippo symbolizes his growth and willingness to help others fix what is broken.

Mrs. Savage represents wisdom, resilience, and the healing power of art and memory. She plays a crucial role in Hercules’s emotional development.

Mr. Moby

Mr. Moby is initially portrayed as a grouchy neighbor but undergoes a transformation when he helps Hercules after Mindy’s injury. His gruff exterior hides a caring individual, and his gesture of driving them to the animal hospital shows his softer side.

His arc parallels the seventh labor’s Cretan Bull, suggesting that even difficult or abrasive individuals have kind and gentle sides. Mr. Moby’s character represents themes of empathy, transformation, and the idea that people are more complex than they appear.

Themes

The Interconnectedness of Personal Growth and Grief in the Shadow of Mythical Expectations

One of the most complex themes in The Labors of Hercules Beal is the interplay between personal growth and grief, framed by the burden of living up to mythic ideals. Hercules Beal’s journey is heavily shaped by his ongoing confrontation with the loss of his parents, a trauma that continues to echo throughout his daily experiences.

His grief is not isolated but weaves into the fabric of his maturation as he faces his own version of the 12 labors, which symbolically represent both external challenges and internal reckonings. Grief, for Hercules, is not something he can overcome by one grand gesture, but it becomes part of his process of learning and adapting.

Each labor mirrors a different facet of Hercules’s coming to terms with his parents’ death. For example, the Hydra labor evokes memories of his father being hooked up to machines, suggesting that grief, like the many heads of the Hydra, regenerates and needs to be faced repeatedly.

Schmidt illustrates that grief is a multifaceted force that, paradoxically, drives Hercules’s development, allowing him to understand both the pain and resilience within himself. This deep sense of personal loss is not just an obstacle for Hercules to overcome, but rather the lens through which he learns the truths about life, love, and human endurance, a reflection of how mythological expectations often burden and shape personal growth.

The Metaphor of Nature and Community as a Mirror of Human Resilience and Transformation

Another complex theme running throughout the novel is the metaphor of nature as a reflection of human resilience and transformation. The Cape Cod setting, with its cycles of seasons and natural beauty, becomes a symbolic canvas for Hercules’s own emotional journey.

His interactions with the environment—whether through rescuing plants, painting leaves, or witnessing the changing seasons—highlight how nature is not merely a backdrop but a mirror for human endurance and growth. Nature’s cycles, such as the autumn leaves turning gold or the stormy nights that threaten to disrupt life, serve as metaphors for the unpredictability of life itself and the inevitability of change.

However, rather than simply observing nature, Hercules engages with it directly, using it as both a challenge and a teacher. His labors often involve physical interaction with the natural world, which forces him to confront his own limitations, as well as the need for patience and persistence.

Nature, then, becomes a stand-in for the resilience and transformation Hercules seeks within himself. Additionally, Schmidt ties nature closely to the theme of community, showing that just as nature is interconnected, so too is human survival dependent on community.

Hercules learns that survival—both his own and that of his family’s business—depends on others, whether it’s his friends or his neighbors. The farm itself, transformed into a temporary school site, represents the convergence of nature and community, showing that both are necessary for personal and collective growth.

The Burden of Heroic Expectations Versus the Reality of Human Vulnerability and Fallibility

Schmidt also explores the tension between mythological heroism and the reality of human vulnerability through the lens of Hercules Beal’s school project. Hercules, burdened by his name and the mythic expectations attached to it, is constantly confronted with the disparity between the grandeur of his namesake’s feats and the often mundane, even painful, reality of his own life.

The 12 labors assigned to him by Lieutenant Colonel Hupfer are ostensibly meant to parallel the legendary trials of the mythical Hercules, but they often reveal more about the boy’s fragility and the vulnerability inherent in growing up without parents. For example, Hercules’s attempt to capture the “Ceryneian Deer” by painting a tree’s leaves reflects not the heroic precision of the mythical Hercules, but a messy, imperfect process that ultimately leads to public embarrassment.

Schmidt uses these moments to explore how the weight of mythic expectations can highlight the discrepancies between idealized heroism and real-world failures. Throughout the novel, Hercules must reconcile the mythic qualities expected of him with his own very human limitations, such as his anger towards Ty or his reliance on others to solve problems.

This theme points to a larger existential struggle: how to live a meaningful life under the shadow of unattainable ideals. Hercules comes to understand that being heroic is less about grand gestures and more about navigating vulnerability, failure, and the small, quiet victories that define human resilience.

The Duality of Memory as Both a Source of Strength and a Burden of Emotional Weight

Memory plays a central role in the novel as both a source of strength and a burden, emphasizing its dual nature. For Hercules, memories of his parents permeate nearly every facet of his life.

These memories, however, do not exist in a single dimension; they act as both a comforting source of continuity and a heavy emotional anchor that keeps him tethered to the past. For instance, when he recalls his father’s death in relation to the hum of the machine, it illustrates how memory is not simply about recall but is embodied, tied to sensory experiences that remain in the present.

This constant presence of memory underlines the way Hercules’s identity is deeply intertwined with the past, yet it also restricts his ability to fully embrace the present. Schmidt uses the metaphor of the Hydra’s many heads to symbolize how memories can regenerate, often bringing emotional turmoil when least expected.

Nevertheless, these memories also provide Hercules with a foundation for understanding love, loss, and what it means to be alive. The novel presents memory not as a static, nostalgic force but as something active, shaping Hercules’s daily experiences and his emotional development.

The dichotomy of memory’s capacity to heal and its potential to trap is central to Hercules’s emotional arc as he learns to navigate a world where memories are inescapable but can also serve as a wellspring of strength.

The Intersection of Human Relationships and the Necessity of Forging One’s Own Path Amidst Loss and Uncertainty

A final thematic strand woven through the novel is the intersection of human relationships and the necessity of forging one’s own path amidst loss and uncertainty. Hercules’s relationships with others—whether his brother Achilles, his friends, or his teacher—are integral to his understanding of himself and the world around him.

However, while these relationships provide critical emotional support, they do not offer clear-cut solutions to the challenges Hercules faces. Schmidt explores the paradox of human connection, suggesting that while relationships are necessary for survival and emotional fulfillment, they cannot erase individual suffering or provide easy answers to life’s most difficult questions.

For example, Hercules’s relationship with Achilles is filled with tension as both brothers navigate their grief in different ways. Achilles assumes the role of caretaker, but his inability to fully comprehend Hercules’s emotional needs creates a rift that the protagonist must learn to bridge.

Similarly, Hercules’s friendship with Elly, Henry, and Ty serves as a source of companionship, but it is his own internal resolve that ultimately allows him to complete each labor. This theme underscores the complex balance between relying on others and finding one’s own strength, particularly in the face of overwhelming uncertainty.

Schmidt suggests that while community and connection are invaluable, there are moments in life where one must face hardship alone and forge a path forward independently. This delicate interplay between communal support and individual resilience is at the heart of Hercules’s journey.