The Last Carolina Girl Summary, Characters and Themes

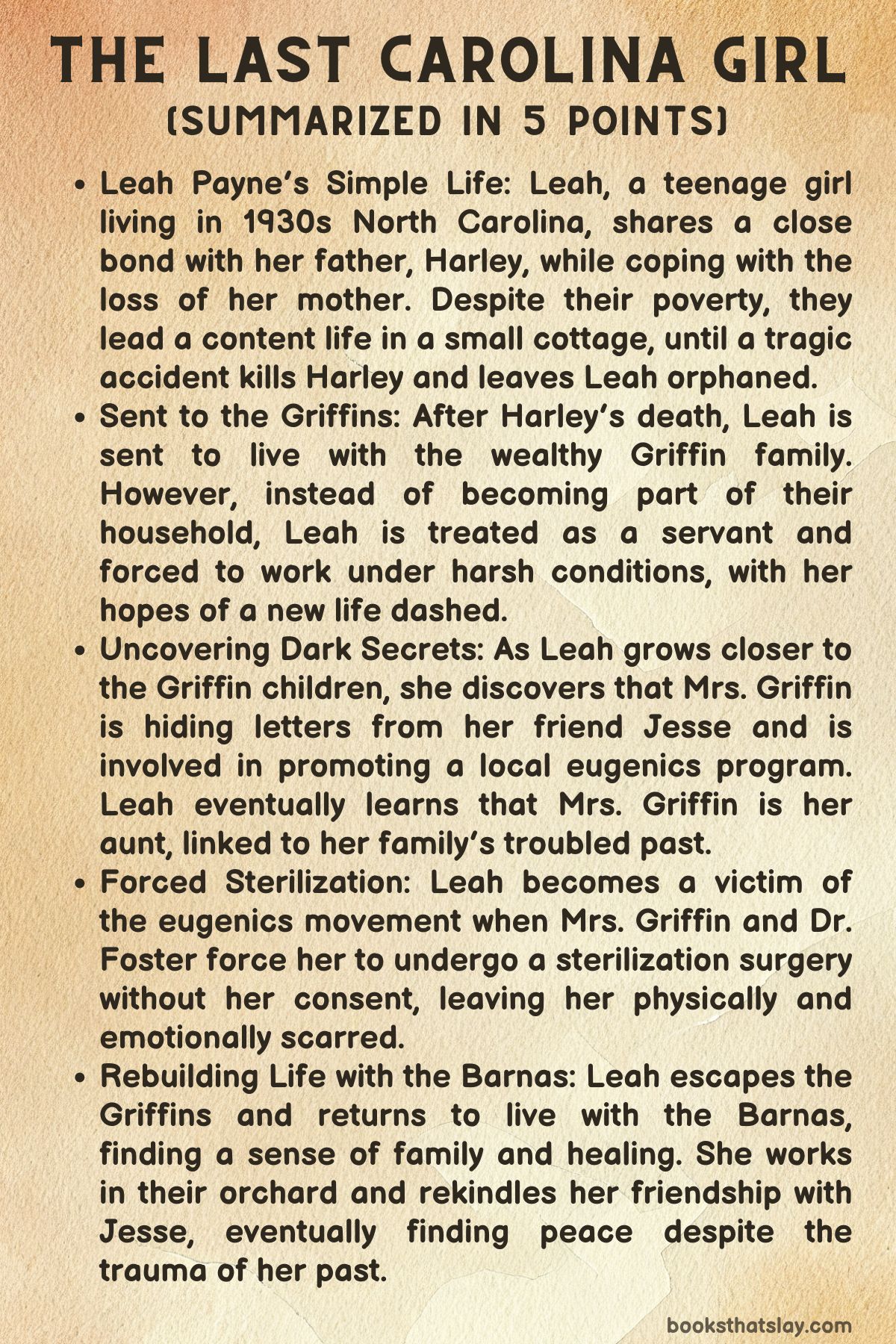

The Last Carolina Girl by Meagan Church is a poignant historical novel set in 1930s North Carolina, bringing together a tale of loss, resilience, and identity. It follows Leah Payne, a teenage girl grappling with personal tragedy after the sudden death of her father.

Orphaned and sent to live with a manipulative family, Leah uncovers dark truths about her past while being caught in the grips of the American eugenics movement. Based on Church’s own family history, this heart-wrenching story explores the themes of autonomy, social class, and the struggle to find belonging in a world that seeks to control and diminish the powerless.

Summary

Leah Payne, a teenage girl growing up along the beaches of North Carolina in the 1930s, is at the center of The Last Carolina Girl. She lives a simple but content life with her father, Harley, in a modest cottage they rent from their wealthier neighbors, the Barnas.

Leah’s mother died during childbirth, leaving Harley and Leah to fend for themselves. Despite their struggles with poverty and Leah’s social isolation at school, father and daughter share a close bond. Each year, Harley marks Leah’s birthday with small but meaningful gifts, a tradition rooted in their memories of Leah’s mother.

One fateful day, a sudden storm changes Leah’s life forever when a tragic accident kills Harley and leaves their home in ruins. Heartbroken and homeless, Leah is temporarily taken in by the Barnas, where she feels safe and supported.

However, her security is short-lived when the Barnas send her to live with a foster family, the Griffins, several hours away. Leah’s hope of finding a new family is quickly shattered when she arrives at their house and is forced into the role of a servant, doing endless chores instead of going to school.

Mrs. Griffin, a cold and manipulative woman, isolates Leah further by controlling her communication with the outside world.

Despite this, Leah forms a close bond with the Griffins’ children, especially the youngest, Mary Ann, and pieces together that she is not the first orphan the Griffins have taken in.

Throughout her stay, Leah discovers that Mrs. Griffin harbors secrets from her own past, which include ties to Leah’s family and a disturbing involvement in the local eugenics movement.

Things take a darker turn when Leah is taken to meet Dr. Foster, who, along with Mrs. Griffin, plans to perform a forced sterilization on Leah. Leah struggles to resist but is eventually sedated and the surgery is carried out.

Upon waking, Leah is filled with rage and sorrow, realizing the extent of the betrayal. It is during this time that Leah learns a shocking truth—Mrs. Griffin is not her mother’s sister, as she initially assumed, but her father’s sister.

Determined to escape the Griffins’ control, Leah confronts them. The next day, Mr. Griffin takes her back to the Barnas’ home. There, Leah begins to rebuild her life, forming strong ties with the Barnas, their housemaid Tulla, and even her beloved cat Maeve.

She takes on meaningful work in Mr. Barna’s garden and eventually rekindles her friendship with Jesse Barna, which later blossoms into a romantic relationship. Though Leah grapples with the emotional scars left by her sterilization, she finds peace with Jesse, settling into a quiet life near the beach.

Characters

Leah Payne

Leah Payne is the novel’s protagonist, whose journey from innocence to maturity unfolds throughout the story. Leah is a complex character shaped by loss, adversity, and the yearning for autonomy.

Her relationship with her father, Harley Payne, forms the emotional foundation of her early life. The deep bond between them defines Leah’s early understanding of love and family.

Harley’s death plunges Leah into grief, but it also acts as a catalyst for her coming of age. Throughout the novel, Leah grapples with the cruelty of the world around her, from schoolyard bullies to systemic oppression.

Her experiences, particularly her forced sterilization, underline her struggle with powerlessness and control over her body. Leah’s dream of living near the beach symbolizes her desire for freedom and security, something she fights to reclaim after being sent to live with the Griffins.

As she navigates through her trauma, Leah grows stronger, finding solace in the idea of a “found family” with the Barnas. By the end of the novel, despite the irreversible damage done to her, Leah achieves a sense of peace, coming to terms with her past and creating a future with Jesse Barna.

Harley Payne

Harley Payne is a loving and dedicated father who raises Leah in humble circumstances. He tries his best to provide emotional support even though he is still grieving the loss of his wife, Emma.

Harley’s character is rooted in his connection to nature, symbolized by the saplings and seashells he gives Leah on her birthdays. These gifts link Leah to her mother’s memory.

Despite their impoverished lifestyle, Harley manages to create a life filled with warmth and love for his daughter. His tragic death early in the novel shakes Leah’s world, setting in motion the events that follow.

Harley represents Leah’s security and emotional anchor. His death forces her to confront the harsh realities of the world.

His absence looms large over the rest of the novel. Leah frequently reflects on his love and the lessons he imparted to her.

Mrs. Griffin

Mrs. Griffin is a multi-layered antagonist who symbolizes the cruelty of societal systems and personal betrayals. Initially appearing as a wealthy, seemingly charitable woman, Mrs. Griffin’s true nature is gradually revealed.

She is manipulative, controlling, and cruel, using Leah as free labor under the guise of offering her a home. Mrs. Griffin embodies the era’s class and power dynamics, believing in eugenicist ideals, which leads her to orchestrate Leah’s forced sterilization.

Her connection to Leah’s family, as her father’s sister, adds a personal layer of betrayal. Mrs. Griffin’s secretive past and her desperation to maintain her social standing further illustrate her complex motivations.

Her treatment of Leah is driven by bitterness over her own difficult upbringing and resentment toward her brother, Harley. Her actions reflect a desire to erase her origins, and Leah becomes a tool in this quest for control.

Mr. Griffin

Mr. Griffin is a more passive character in contrast to his domineering wife. His role in the household is defined by his avoidance of conflict, particularly with Mrs. Griffin.

He is often absent due to his job as a traveling salesman. When present, he submits to his wife’s authority, never challenging her cruel treatment of Leah.

However, his more subdued nature allows him moments of decency. He eventually intervenes by returning Leah to the Barnas after learning about Jesse’s letters.

Though he lacks the strength to confront his wife directly, his decision to return Leah to the Barnas marks a small redemption. This signals a latent sense of responsibility in his character.

Jesse Barna

Jesse Barna plays the role of Leah’s loyal friend and eventual romantic partner. As the son of the wealthier Barnas, Jesse’s relationship with Leah is one of quiet support and understanding.

He witnesses Leah’s struggles with bullying at school and offers her emotional solace. Though he does not directly intervene, his friendship provides Leah with the emotional grounding she needs.

After Leah is sent to live with the Griffins, Jesse’s letters represent her lifeline to the world she longs to return to. Their eventual reunion rekindles Leah’s hope.

Jesse’s life trajectory—going to college and later enlisting in the military—shows his path to adulthood running parallel to Leah’s. Their eventual romantic relationship offers Leah a sense of stability and belonging, symbolizing her reclamation of love and agency after years of trauma.

Emma Payne

Emma Payne, Leah’s mother, dies during childbirth and is not physically present in the novel. However, her absence plays a significant role in shaping Leah and Harley’s lives.

Emma is remembered through the annual rituals Harley and Leah perform, such as planting saplings and placing seashells near her grave. She symbolizes the loss that haunts both Harley and Leah.

Her memory becomes a tender point of connection between father and daughter. Emma’s death also highlights the theme of maternal absence in Leah’s life, which contrasts sharply with the harshness of Mrs. Griffin.

The Barnas (Mr. and Mrs. Barna)

The Barnas, though secondary characters, serve as a stark contrast to the Griffins. They represent kindness, generosity, and the possibility of a chosen family.

After Harley’s death, they take Leah in and provide her with a semblance of care. Circumstances, however, lead them to send her away to the Griffins.

The Barnas’ decision to eventually welcome Leah back into their home reinforces the idea that family is not necessarily tied to blood. Leah can find love and acceptance beyond her biological relatives.

Mr. Barna’s decision to repair Leah’s childhood home serves as a symbolic act of restoration and healing. This allows Leah to reclaim her past and build a new future.

Tulla

Tulla is the Barnas’ housemaid and plays a maternal role in Leah’s life after Harley’s death. She helps care for Leah during her most vulnerable moments, especially as Leah grieves the loss of her father.

Tulla represents a source of comfort and stability for Leah. Her presence in the Barnas household helps create the sense of found family that Leah cherishes by the end of the novel.

Mary Ann Griffin

Mary Ann Griffin is the youngest of the Griffin children. She becomes Leah’s closest companion during her time with the family.

She, like her siblings, often finds herself at odds with Mrs. Griffin’s strict and oppressive rules. Mary Ann’s friendship with Leah is one of genuine affection, and her small acts of kindness, such as sneaking Leah food after her sterilization procedure, demonstrate her compassion.

Mary Ann’s bond with Leah highlights the contrast between the innocent, empathetic nature of the children and the harshness of their mother.

Dr. Foster

Dr. Foster represents the institutional cruelty of the eugenics movement that underpins much of the novel’s conflict. As the doctor who performs Leah’s forced sterilization, he symbolizes the violation of Leah’s bodily autonomy.

His brief examination of Leah is cold and clinical, reducing her to a set of perceived deficiencies rather than acknowledging her as a person. Dr. Foster’s role in the narrative reflects the broader societal abuses of power and the dehumanizing effects of the eugenics movement.

Themes

The Intersection of Class, Power, and Identity

In The Last Carolina Girl, Meagan Church delves into the complex relationship between class, power, and identity, showing how social and economic status deeply influences individual agency. Leah Payne’s lower-class status places her in a position of subjugation from the outset.

Her inability to make friends at school due to her socioeconomic background and developmental delays mirrors the larger societal structures that marginalize the underprivileged. Leah and her father’s humble existence in a small cottage highlights their struggle with material deprivation, yet also their contentment with the richness of their emotional bond.

This contentment contrasts sharply with the Griffin family, who, despite their wealth, exist within a deeply dysfunctional power dynamic. Mrs. Griffin’s desire to maintain her status in upper society drives her to exploit Leah, mirroring broader patterns of exploitation of the lower class by the upper class.

The novel critiques the way economic power can strip individuals of their autonomy, as Leah is forced into servitude with the Griffins. This sense of exploitation culminates in the sterilization plot, where Leah’s agency is stripped entirely by those with greater social power.

Church deepens the theme of how class structures mold and limit identity, making Leah’s fight for autonomy both personal and symbolic.

The Legacy of Trauma and Intergenerational Grief

Church also weaves the theme of trauma—both personal and intergenerational—into Leah’s journey, showing how deeply it shapes her sense of self. Leah’s trauma begins with the loss of her mother at birth, a grief her father, Harley, never fully overcomes.

His yearly gifts of a sapling and seashell to Leah are poignant markers of unresolved mourning. They reflect Harley’s attempts to commemorate his lost wife while raising his daughter in an environment of love, yet constant sorrow.

Leah’s narrative is marked by compounded grief—the death of Harley being the catalyst that shatters her world and forces her into a life of exploitation. Her father’s death is not just a personal loss but the beginning of a process of erasure, as her autonomy is taken away through her forced sterilization.

This intrusion into her body, done without her consent, marks a generational trauma tied to the eugenics movement. The sterilization echoes her mother’s death in childbirth, suggesting that Leah’s pain is connected to an ongoing legacy of female suffering within her family.

Furthermore, Mrs. Griffin’s role as Leah’s aunt, and her neglect and cruelty, reflects how familial trauma is inherited and perpetuated. The novel suggests that grief, left unresolved, transmits through generations, trapping individuals in cycles of loss, suffering, and subjugation.

The Conflict Between Bodily Autonomy and State-Sanctioned Control

One of the most harrowing themes in The Last Carolina Girl is the exploration of bodily autonomy, particularly through the lens of the American eugenics movement. Leah’s forced sterilization by Dr. Foster and Mrs. Griffin is not only a violation of her body but a profound expression of the state’s control over individual lives.

The eugenics program, which sought to eliminate “undesirable” traits from the population, is depicted as an oppressive system that strips marginalized individuals of their rights. Leah’s seizures make her vulnerable to this type of state-sanctioned control, as her medical condition is seen as a justification for sterilization.

Through Leah’s story, Church critiques this dark chapter in American history, showing how institutional power can intrude into the most intimate aspects of an individual’s life—control over reproduction. The sterilization not only physically alters Leah, but it psychologically scars her, marking a lifelong battle for autonomy over her own body.

The novel challenges readers to think about the ways in which historical and modern institutions continue to exercise power over individuals’ bodies. Leah’s eventual journey towards reclaiming her autonomy is an act of resistance against this institutional control, but her loss of fertility remains a permanent scar, reflecting the devastating consequences of such systemic abuse.

The Construction of Female Identity in a Patriarchal and Class-Conscious Society

The theme of female identity, as it intersects with both class and patriarchy, runs deeply through Leah’s story. Throughout The Last Carolina Girl, the female characters navigate a society that constrains their autonomy and defines them by their relationships to men and their reproductive abilities.

Leah’s mother’s death in childbirth casts a long shadow over Leah’s life, setting the tone for a narrative deeply concerned with the role of women within a patriarchal structure. Mrs. Griffin, who initially appears as a powerful matriarch, is ultimately revealed to be a woman trapped by societal expectations.

Her cruel treatment of Leah, while unforgivable, can be understood as a product of her own survival mechanisms. Mrs. Griffin’s adherence to the eugenics movement, a patriarchal pseudoscience, shows how deeply entrenched societal values infiltrate women’s lives, forcing them to uphold structures that oppress other women.

Leah, on the other hand, represents a different path—a woman struggling to forge an identity in a world that continually tries to define her by her weaknesses, her class, and her perceived inferiority. The novel emphasizes the limits of female agency in a society that uses women’s bodies as sites of control.

Church critiques the complex web of societal expectations that dictate women’s lives. True liberation, the novel suggests, can only come through the rejection of these harmful structures.

The Reclamation of Found Family and Self-Determination

At its heart, The Last Carolina Girl is a narrative about the reclamation of self and the building of found family. These themes reflect Leah’s gradual journey toward self-determination.

Leah’s relationship with her father, Harley, is a source of love and grounding. But after his death, she is forced into a world that tries to strip her of her identity.

The Griffins’ exploitation and the state’s eugenic control are all attempts to define Leah according to their own needs and societal expectations. However, Leah’s resilience lies in her ability to construct her own sense of family and selfhood, despite the attempts to erase her autonomy.

Her bond with Jesse, her friendship with Tulla, and her eventual return to the Barnas are all parts of her reclamation of a life that has meaning on her own terms. By choosing to build her own family with Jesse and live at the beach, Leah symbolically takes back control over her destiny.

While the loss of her fertility remains a point of deep pain and grief, Leah’s ability to find peace in her life demonstrates her inner strength. Church frames the theme of found family not just as a source of healing, but as a necessary act of survival for those marginalized by society.

Through this, Leah’s story becomes one of triumph over adversity, where self-determination is the ultimate form of resistance against those who would seek to define her life for her.