The Liberty Scarf Summary, Characters and Themes

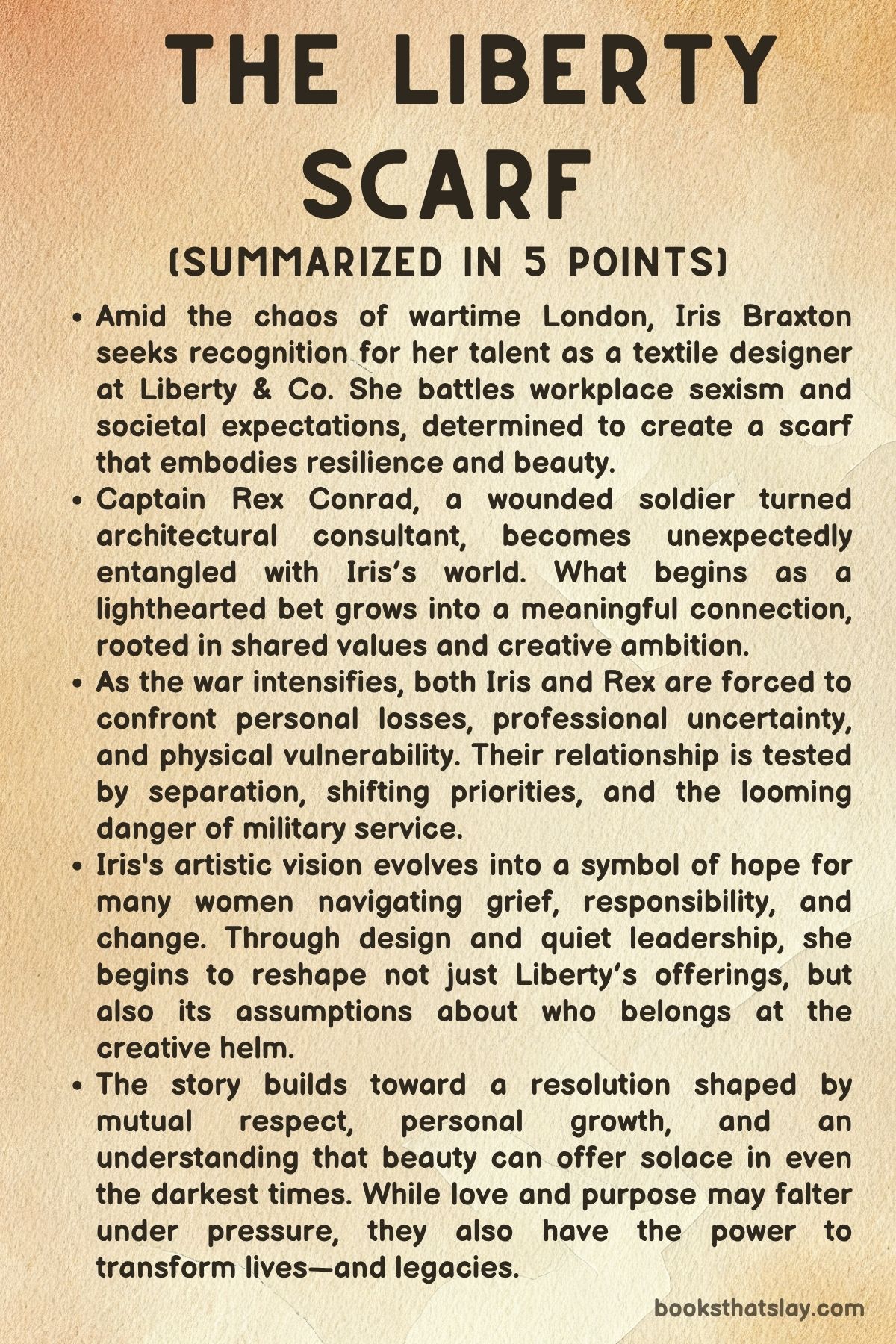

The Liberty Scarf by Aimie K. Runyan, J’nell Ciesielski, and Rachel McMillan is a collaborative historical novel that interlaces the lives of three women across different war-torn fronts in World War I.

Through their distinct but interconnected stories, the novel explores how creativity, resilience, and love persist even amid devastation. The Liberty scarf itself becomes the central object—a piece of fabric bearing symbols of survival, sacrifice, and hope. From the bustling heart of London to the trenches of France and hospitals of Belgium, each woman shapes her destiny while finding comfort and meaning in artistry and connection. It’s a moving portrait of courage stitched together across continents.

Summary

In December 1917, London is still under the shadow of war when Iris Braxton, an ambitious paint girl at Liberty & Co. , dreams of modernizing Britain with bold colors and contemporary designs.

Working in a company that values outdated aesthetics and denies women creative opportunities, Iris is frequently dismissed by her manager, Mr. Fletcher.

Despite these obstacles, she continues sketching scarves that reflect her vision of a postwar world full of hope and beauty. Her only support system is her friend Sara, a fellow paint girl and soon-to-be sister-in-law, who encourages her to persist.

Iris’s path crosses with Captain Rex Conrad, a wounded soldier and talented architect, when she seeks out Mr. Stewart-Liberty at the Argyll Arms pub to pitch her scarf designs.

After slipping and damaging her sketches, Rex helps her, intrigued by her determination. He agrees to show her work to Stewart-Liberty if she’ll attend a ball with him.

Their chemistry grows from this encounter, with flirtation and shared admiration developing into a deeper connection.

As their relationship slowly evolves, Iris finds herself seen not just as a worker but as a creative mind. Rex’s support, along with encouragement from her father—a master printer at Liberty’s Merton Abbey facility—rekindles her artistic purpose.

A visit to the printworks further connects her to Liberty’s rich history of handcrafted textiles. On Christmas Eve, despite the chaotic day, Iris meets Rex at the ball, where they enjoy a magical evening that deepens their bond.

However, Iris overhears that Rex originally asked her to the ball on a bet. Rather than end things, she cleverly demands another date, asserting her dignity and strength.

Rex, clearly taken by her, agrees.

As they prepare for an opera date, Iris reflects on how Rex is helping her believe in her own value. Their evening is interrupted by an air raid, and when the audience flees to the basement, Rex’s calm reassures Iris.

Afterward, tragedy strikes: Iris’s parents’ home is bombed. Her father is injured, and their home is uninhabitable.

Rex offers his godfather’s countryside estate for her family’s recovery. Though hesitant, Iris accepts, and the peaceful environment inspires her to create a new scarf design called “Feathered Hope.” This design symbolizes rebirth and optimism and is soon approved by Stewart-Liberty. It becomes a bestseller, giving Iris professional acclaim and emotional validation.

The war continues to cast its shadow. Rex is called back to the front, and though injured, he serves again.

Their letters become lifelines, filled with warmth, wit, and mutual encouragement. When Rex suffers another injury and loses a leg, he still writes to Iris, asking her for a drawing of herself to keep with him.

Meanwhile, Iris’s design becomes a symbol of resilience for others, too, and her success opens the door to international opportunities. She is invited to Paris to collaborate with Liberty’s French team.

When she arrives, a telegram diverts her to Strasbourg for a surprise—hinting at a long-awaited reunion with Rex.

Alongside Iris’s journey, the novel introduces Geneviève, a Signal Corps switchboard operator in France. Exhausted by the war, Geneviève faces betrayal when her colleague Patricia neglects duty in favor of a secret relationship with Corporal Peter Blake—Geneviève’s former love.

Her confrontation with Peter is met with classist insults, but Geneviève reclaims her power by reminding him of her military rank and self-worth. She reflects on a past connection with Maxime, a Frenchman who respected her.

Writing to Maxime helps her find closure and renew her sense of purpose.

In the women’s barracks, Patricia becomes socially isolated, and Geneviève’s leadership earns admiration. At a concert intended to lift spirits, an artillery barrage brings more chaos.

Geneviève uses her treasured Liberty scarf to bandage a wounded violinist, sacrificing sentimentality for compassion. The armistice is declared soon after, but Geneviève is contemplative rather than joyful.

She wonders about her future, her status in civilian life, and the fate of Maxime. A final diary entry to him closes her chapter with hope tempered by realism.

Meanwhile, Clara Janssens, a Belgian nurse, uses storytelling and art to soothe wounded soldiers. In letters to her father, she recounts her growth from a dutiful daughter to a resilient caregiver.

She develops a deep connection with Roman Allaire, a French violinist recovering from illness. As he heals, their bond strengthens, built on a shared appreciation for music, art, and quiet resilience.

Clara draws comfort from memories of her late friend Annelise and keeps the Liberty scarf as a token of remembrance.

Clara and Roman’s separation leads to poignant letters from Roman, who performs with Symphonie L’Armée across Europe. His messages to Clara express longing and his desire to heal.

Clara, back in Belgium, channels her grief into caregiving. Eventually, she receives a telegram from Roman urging her to meet him in Strasbourg.

Their reunion is tender, filled with the pain of lost time and the hope of a renewed future. Roman gifts Clara the scarf, now cleaned and embroidered by his mother, as a symbol of their shared past and a hopeful tomorrow.

The novel’s closing scene brings all the threads together in Strasbourg’s Christmas market. Clara, Roman, Geneviève, and eventually Iris and Rex gather, their stories intersecting through the journey of the scarf.

As Clara passes the scarf to Geneviève, who then gives it to another grieving nurse, the item transforms into a living emblem of connection and endurance. Iris and Rex kiss beneath the market lights, their love reaffirmed, and Geneviève is reunited with Maxime, who had not forgotten her.

The final message of The Liberty Scarf is one of rebuilding—of relationships, identities, and futures. Through love, art, and quiet acts of courage, the characters find meaning in the aftermath of chaos.

The scarf itself, passed from hand to hand, becomes a testament to survival and the possibility of joy.

Characters

Iris Braxton

Iris Braxton is the emotional and artistic heart of The Liberty Scarf. A gifted textile designer working in the paint room at Liberty & Co.

, Iris is both a visionary and a fighter. Her struggle against institutional gender barriers and aesthetic conservatism at Liberty embodies the broader themes of transformation and female empowerment in a postwar world.

Although her managers ignore her modernist scarf designs in favor of outdated styles, Iris remains quietly defiant, using art as a means to express hope and rebuild a shattered society. Her creativity is deeply personal—rooted in her father’s craftsmanship as a master printer and in her own conviction that beauty can be revolutionary.

Iris’s relationship with Rex Conrad is central to her development. It starts as a serendipitous encounter but evolves into a partnership defined by mutual respect and creative inspiration.

Rex sees her not just as a muse but as an artist in her own right, and this validation catalyzes her growth. Even in moments of vulnerability—whether confronting the bombing of her family home or the revelation of Rex’s early bet—Iris exhibits a blend of courage, grace, and wit.

Her “Feathered Hope” scarf design becomes emblematic of postwar recovery and resilience, not just for Liberty’s clientele but for Iris herself. By the novel’s end, she emerges as a symbol of how women can reshape the world—not by abandoning beauty, but by wielding it as an act of endurance and imagination.

Captain Rex Conrad

Captain Rex Conrad is a complex blend of gallantry, sensitivity, and resilience. A wounded war hero with a background in architecture, Rex represents both the old-world ideals of duty and the new possibilities of peacetime creativity.

His commission to help redesign Liberty’s premises is not just a testament to his professional ability, but also a strategic choice meant to reassure a demoralized public with a visibly heroic figure. Yet Rex is far more than a uniform.

Beneath his confident exterior is a man searching for meaning in the chaos of war, someone who finds unexpected inspiration in Iris’s art and spirit.

Rex’s charm is tempered by emotional depth and vulnerability, especially after the trauma of war and his eventual severe injury. His relationship with Iris matures from flirtation to partnership, built on encouragement, shared values, and artistic mutuality.

When he uses his resources to help Iris’s family and repeatedly uplifts her creative ambitions, he defies the rigid masculinity often expected of men in his position. Even after losing a leg, Rex remains determined to support Iris from the frontlines and through letters—his humor and steadiness never falter.

He ultimately becomes a model of modern masculinity, one that honors both bravery and tenderness, ambition and love.

Geneviève

Geneviève is a woman shaped by war, duty, and emotional turmoil. As a lieutenant in the Signal Corps, she is a commanding presence who earns the respect of her peers and subordinates alike.

Her stoicism masks deep wounds, particularly from her broken relationship with Peter Blake, a betrayal that is layered with class prejudice and personal humiliation. Yet Geneviève never succumbs to bitterness.

Instead, she transforms pain into purpose, asserting her authority and proving her worth beyond romantic affiliations or social rank.

Her arc is one of reclamation and self-empowerment. Whether writing a vulnerable letter to Maxime or using her cherished Liberty scarf as a tourniquet in a moment of crisis, Geneviève consistently chooses action over despair.

She is a quiet but potent force of leadership, especially when chaos erupts during the concert. Her respect among her peers grows not because she demands it, but because she earns it through composure, sacrifice, and competence.

Even in the ambiguity of post-armistice life, Geneviève faces the future with clear eyes and an open heart, willing to carry memory without being shackled by it. Her reunion with Maxime in the end is not merely romantic—it is the fulfillment of a hard-fought emotional journey.

Clara Janssens

Clara Janssens embodies the compassionate resilience of wartime caregivers. A Belgian nurse who finds meaning in art, stories, and human connection, Clara is a nurturing soul shaped by loss and hope.

The death of her friend Annelise and the shadow of potential assault by Seth Martin mark her with trauma, yet she never lets darkness define her. Clara channels her grief into service, tending to the wounded in makeshift hospitals and telling stories that keep humanity alive amid carnage.

Her bond with Roman Allaire is born not of convenience but of soul-level understanding. Through her, Roman finds solace and through him, she reconnects with her own sense of wonder and longing.

Clara’s evolution is poetic; she grows from a dutiful daughter to a woman who claims agency over her own heart and vocation. The scarf, once Annelise’s and later a symbol of Roman’s survival, passes through Clara’s hands like a talisman of memory, connection, and continuity.

In the end, when she and Roman reunite and share a kiss beneath Strasbourg’s festive lights, Clara’s story crystallizes into a powerful message: love, when nourished by art and empathy, can be both healing and redemptive.

Roman Allaire

Roman Allaire is a figure of fragile grace and unspoken strength. A French violinist turned wartime musician, Roman uses his art not merely to entertain but to soothe the battered souls of soldiers.

His music is a stand-in for words too heavy to speak and memories too painful to revisit. His connection with Clara is born in silence and sustained through stories, melodies, and shared glances—moments that carry emotional truths louder than dialogue.

Wounded in both body and spirit, Roman’s arc is one of quiet endurance. Even after sustaining injury and partial loss of the very arm that once moved a bow with fluidity, he remains determined to find joy, purpose, and love.

His letters to Clara, rich with poetic longing, reveal a man deeply attuned to beauty and emotional truth. When he finally reunites with Clara, he does not present himself as a tragic figure, but as someone reborn through love.

The gift of the scarf, lovingly cleaned and embroidered by his mother, is an act of profound vulnerability and symbolic closure. Roman is a reminder that even in brokenness, there is music—and in music, the possibility of healing.

Patricia and Peter Blake

Patricia and Peter Blake serve as cautionary contrasts to the novel’s central characters. Patricia, once popular, allows personal desires to eclipse professional duty, abandoning her station for an affair with Peter.

Her negligence endangers lives and shatters the trust of those around her. Her character illustrates the consequences of selfishness in a time that demands unity and sacrifice.

Peter Blake, meanwhile, is a study in class arrogance and emotional manipulation. His betrayal of Geneviève is rooted not just in infidelity, but in his inability to value a woman who defies his social expectations.

His insults during their confrontation are barbed with elitism, but Geneviève’s firm rebuttal highlights his moral and emotional smallness. Together, Patricia and Peter embody the perils of self-interest and the decay of outdated hierarchies in a world struggling to redefine itself.

Maxime

Though mostly absent from the narrative’s central action, Maxime’s presence looms large in Geneviève’s emotional world. A cultured Frenchman and Geneviève’s former wartime correspondent, Maxime represents a sanctuary of respect, intellect, and genuine connection.

His letters offer solace during dark days, and their correspondence becomes a channel for mutual affirmation and quiet longing.

When Maxime finally reappears in Strasbourg, it feels like a resurrection—not of an old love, but of a long-deferred hope. His reunion with Geneviève under the starlight is gentle and symbolic, affirming that love built on mutual respect and emotional courage can survive even the worst crucibles of war.

He is a man who, unlike Peter, values strength in others and honors the emotional labor women have carried through the war. His character, though understated, completes the novel’s mosaic of redemptive love.

Mr. Fletcher and Mr. Ivor Stewart-Liberty

Mr. Fletcher, Iris’s manager at Liberty, symbolizes the resistance to change and the stagnation of tradition.

His refusal to consider new designs and his preference for imported, uninspired textiles encapsulate the societal reluctance to allow women and innovation to disrupt the status quo. He is not villainous, but his rigidness serves as a barrier Iris must overcome.

Conversely, Mr. Ivor Stewart-Liberty, the eccentric owner of the department store, is a paradox—both traditionalist in his Tudor architectural vision and progressive in his eventual embrace of Iris’s scarf design.

Stewart-Liberty’s decision to publish the “Feathered Hope” scarf demonstrates a turning point in institutional acknowledgment of new voices. His character is pivotal, if not prominent, in enabling the societal shift that the novel so beautifully portrays.

Together, these two men represent the opposing forces at play in a world on the brink of reinvention.

Themes

Female Agency and Professional Ambition

In The Liberty Scarf, Iris Braxton’s struggle to assert herself as a creative professional in the male-dominated textile industry forms a central narrative arc, reflecting the broader limitations placed on women during wartime Britain. Iris is a skilled “paint girl” at Liberty & Co.

, brimming with artistic vision and the desire to modernize traditional textile design. Yet she repeatedly encounters condescension, especially from her superior Mr.

Fletcher, whose preference for conservative aesthetics and resistance to female designers represent entrenched patriarchal norms. Iris’s ambitions are not merely personal but are driven by a belief in the restorative power of art—a conviction that beauty and innovation can offer solace and renewal in a traumatized postwar society.

Her refusal to be silenced or sidelined manifests in her persistent sketching, her attempts to pitch her designs, and ultimately, her success with the “Feathered Hope” scarf. This journey underscores the emergence of female agency during wartime, as societal needs and the absence of men from the workforce begin to unsettle traditional gender roles.

Similarly, Geneviève’s command as a lieutenant in the Signal Corps further illustrates women claiming space in historically male domains. She not only asserts her authority in a professional hierarchy but redefines herself through her competence, refusing to let heartbreak or social status determine her worth.

Clara’s evolution from a gentle storyteller to a skilled wartime nurse also reveals how necessity and crisis forge women into powerful agents of care, leadership, and change. Collectively, these arcs portray female ambition not as a rebellion, but as a rightful reclamation of autonomy and professional identity.

The Redemptive Power of Art

Throughout The Liberty Scarf, artistic expression—whether through textile design, music, painting, or storytelling—functions as a redemptive force that brings healing, dignity, and meaning in the midst of violence and loss. Iris’s scarf designs are more than aesthetic innovations; they serve as emotional antidotes to war-weariness.

Her “Feathered Hope” pattern, infused with symbolism and vibrant hues, becomes a commercial and spiritual success, offering consumers a small but significant balm during a time of national mourning. For Iris, art becomes a means of survival and resistance, a way to transform suffering into beauty.

This redemptive quality is echoed in Roman’s role as a violinist with the Symphonie L’Armée. His music, performed in bombed-out halls, doesn’t just entertain—it dignifies grief, gives voice to longing, and reconnects soldiers with fragments of humanity.

Even in the trenches and hospital rooms, his performances act as bridges between life and death, sorrow and serenity. Clara, too, treats art as medicine.

Her love for Bruegel’s paintings and her penchant for storytelling are not hobbies but methods of care—ways to elevate her patients beyond their wounds and fears. Art here is not passive or decorative; it is essential, nourishing the spirit when everything else is broken.

By making the Liberty scarf itself a vessel for memory, comfort, and tribute, the novel suggests that art has the unique ability to capture and preserve human resilience. It allows those scarred by war to not only remember but also to dream again.

Love as Healing and Reclamation

Romantic love in The Liberty Scarf is not portrayed as escapist fantasy but as a grounded, often hard-won source of healing. Iris and Rex’s evolving relationship is built on mutual admiration, shared wounds, and acts of everyday kindness.

Rex, despite his injuries and past arrogance, sees Iris for who she is—a gifted artist with a vision that deserves support. Their bond matures slowly, moving through misunderstandings, war trauma, and eventual physical separation.

It is through letters and memory, rather than mere proximity, that they deepen their connection. In Rex’s championing of Iris’s career and Iris’s empathy toward his suffering, love becomes a conduit for restoration.

Similarly, Clara and Roman’s relationship unfolds through storytelling, caregiving, and music, grounded in the mutual understanding of pain. Their love is tempered by grief, especially Clara’s memories of Annelise and Roman’s physical limitations post-war.

Yet, it flourishes precisely because it offers a future not as compensation for suffering, but as affirmation that tenderness and joy are still possible. Geneviève and Maxime’s bond, too, endures despite silence and uncertainty, representing a different kind of love—one rooted in emotional and intellectual respect.

These relationships do not erase the damage of war, but they help characters reclaim parts of themselves. Love, in this narrative, is not a fairy tale resolution but a fragile, persistent gesture of faith in life after devastation.

War’s Lasting Psychological Impact

The psychological toll of war shadows every character in The Liberty Scarf, shaping their decisions, relationships, and sense of self. Rex, though celebrated as a hero, carries the invisible burden of trauma and guilt, which becomes evident in his restlessness, self-effacing humor, and protective instincts.

His wartime injuries and eventual amputation don’t just alter his physical reality but challenge his identity as a soldier and man. Iris, though not a frontline combatant, suffers from survivor’s guilt after her family is bombed while she is safe and enjoying a night out.

Her guilt is compounded by her need to balance personal ambition with familial responsibilities, creating a constant emotional tension. Geneviève’s character is also marked by emotional fatigue and betrayal—both romantic and institutional.

Her poise as a lieutenant masks deep-seated questions about self-worth, class discrimination, and loneliness. Clara, haunted by Annelise’s death and her own near-assault, channels her trauma into nurturing others, but her letters reveal a lingering fragility.

Even the moments of peace—Christmas balls, opera nights, and market strolls—are frequently interrupted by air raids, hospital alarms, or memories that refuse to fade. The novel doesn’t offer easy healing but portrays recovery as a process, often non-linear and incomplete.

War’s effects are not confined to the battlefield; they infiltrate homes, workspaces, and hearts. The characters’ eventual steps toward healing are portrayed with quiet realism, emphasizing that the end of fighting does not mean the end of suffering.

Hope and Renewal in the Face of Destruction

Amid the bleakness of war, The Liberty Scarf foregrounds the power of hope—not as blind optimism but as a hard-earned, conscious act of renewal. Iris’s scarf design titled “Feathered Hope” encapsulates this sentiment, using peacock feathers and sunbursts to suggest resurrection and continuity.

This motif is echoed across the three women’s stories: Iris finds new purpose in her art and love; Geneviève reclaims her self-worth despite institutional sexism and personal betrayal; Clara nurtures her patients and heartbroken companions back to emotional wholeness. Hope in the novel is tangible—stitched into fabric, played on violin strings, written in unsent letters.

It is passed from one character to another, most symbolically through the Liberty scarf, which becomes a token of remembrance, solidarity, and love. Even in a world riddled with bomb craters and amputated futures, the scarf moves from hand to hand, reminding its bearers that something beautiful can endure.

The characters’ acts of kindness—housing displaced families, composing letters, performing music, or simply showing up—are all declarations that life continues. The story closes not with grand victories but with intimate moments: kisses exchanged in wintry squares, telegrams inviting reunions, and the quiet acceptance of love returned.

These moments signal not naïveté but resilience, the belief that from the ashes of destruction something lasting and meaningful can still be built. Hope, then, is not a fleeting sentiment—it is the backbone of the entire narrative.