The Librarians by Sherry Thomas Summary, Characters and Themes

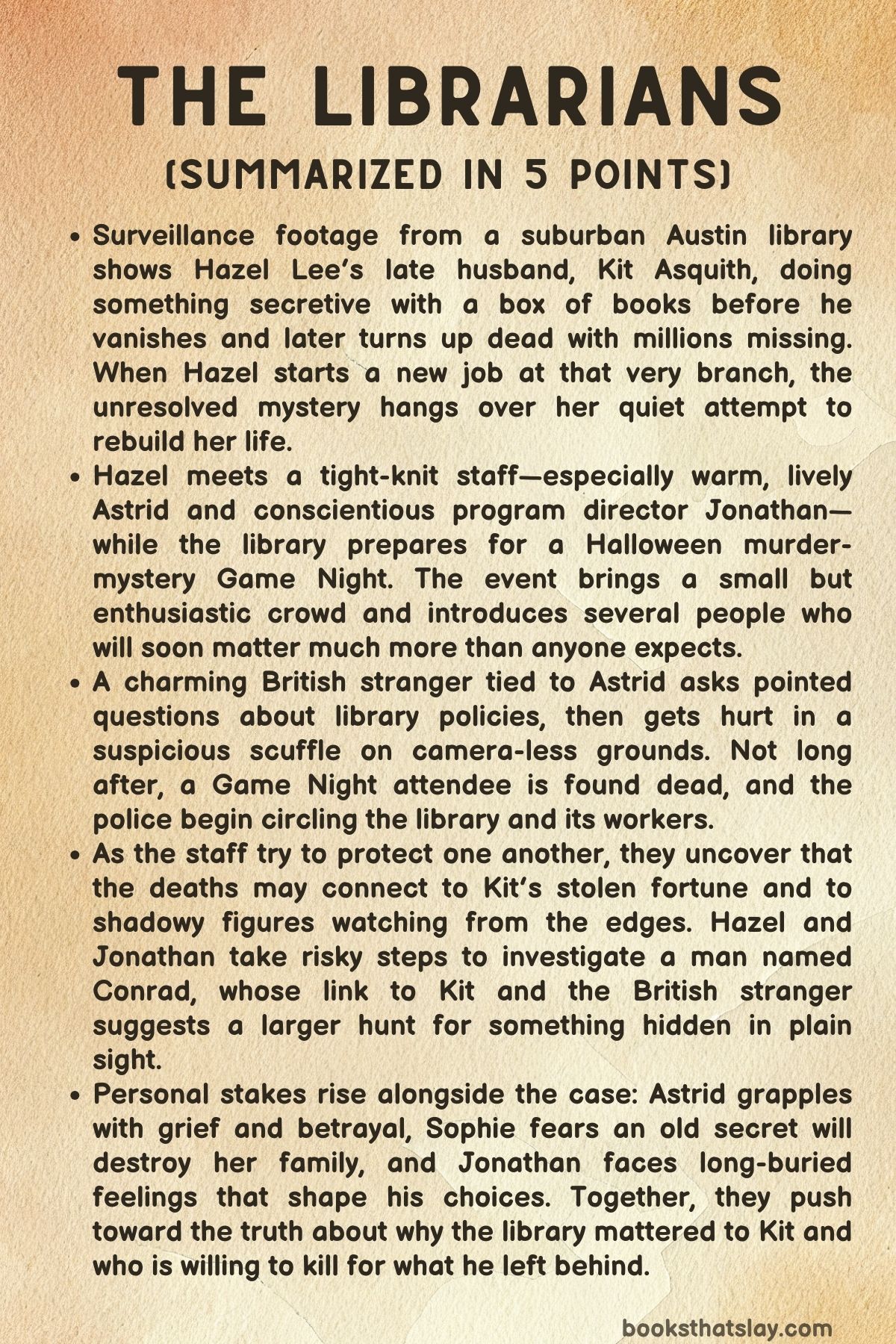

The Librarians by Sherry Thomas is a mystery set in a suburban Austin public library where the quiet routines of staff and patrons hide dangerous secrets. When Hazel Lee, a recently widowed former lawyer, takes a job at the library to rebuild her life, she walks into a puzzle tied to her late husband Kit Asquith, who died after stealing a fortune.

Around her, coworkers Astrid, Sophie, and Jonathan carry their own unfinished stories, while a stranger’s odd behavior in the stacks hints that the library holds more than books. As deaths mount and motives blur, the librarians become reluctant investigators of a crime that reaches far beyond their shelves.

Summary

A suburban Austin library’s security footage captures Kit Asquith lingering in the stacks for days, inspecting bindings and quietly trading books from a heavy box into the shelves. Weeks later, Kit is dead after stealing twenty-five million dollars through an embezzlement scheme, and no one can explain what he did in the library or where the money went.

The mystery sits dormant until Hazel Lee returns to her childhood neighborhood and begins work at that same branch. Hazel is newly widowed—Kit was her husband—and she has taken the job at her grandmother Nainai’s urging.

She wants something steady, a life that doesn’t require constant vigilance or reinvention.

Hazel’s first day is ordinary on the surface. Astrid, a bright and friendly librarian, introduces her to the team: Sophie, the administrator; Jonathan, who runs programs; and clerks Inez and Raj.

Hazel proves efficient at desk work and book processing. The branch is preparing for a Tuesday Game Night themed around Halloween murder-mystery board games.

The staff hopes it will draw community interest, and Astrid is especially excited.

That afternoon, Perry, a British man Astrid once dated, appears unexpectedly. Months earlier, Astrid and Perry had met outside the library, had a fast, intense week together, and then he vanished without explanation.

Now he acts as if he barely knows her and approaches Hazel with a strange research question: how long a library book can sit untouched on shelves, and what policies affect that. He claims to be working on a film script.

Hazel pulls Jonathan in to answer, but Astrid watches the exchange with growing hurt. When Perry later apologizes privately, he still refuses to explain why he left or why he has returned.

Astrid feels used and humiliated.

On Hazel’s second day, enormous book-donation boxes block the entrance. While she hauls them into storage, Perry keeps turning up, offering help, and Hazel repeatedly refuses.

Jonathan, trying to be kind, awkwardly hints at setting Hazel up with a friend, then realizes she is widowed and backs off, embarrassed. During the afternoon, a fight erupts near the public computers.

Astrid rushes over to stop it and threatens to ban both men. One punches the other and runs.

The injured patron is Perry, bleeding and disoriented. A bystander calling himself Tarik Ozbilgin, claiming to be an army medic, checks Perry for concussion and urges Sophie to call an ambulance.

Perry refuses medical care or a police report and leaves. Hazel asks about security footage but learns the branch cameras have not been working.

Soon after, Sophie finds an origami “love knot” on her office floor with a note: “I know you’re keeping a secret. We should talk.

” She remembers similar notes from earlier programs and senses someone is monitoring her. That evening Game Night goes well despite low registration.

Patrons show up in costume, play Clue and other mysteries, and the library feels alive. After closing, Sophie and her daughter Elise lock up and notice a black Audi decorated with creepy Halloween stickers.

Someone calls Sophie by name and asks to speak with her. Sophie is left unsettled.

Hazel goes home to Nainai’s house and checks the security cameras her grandmother installed. She sees nothing but still feels watched, a familiar sensation from her years in Singapore.

Upstairs she opens a package containing pieces of a book-themed board game she has been designing—a project that now feels like another unfinished part of her life. Elsewhere, Jonathan sits alone with his cat, rereading a poem he once published anonymously about desires he kept hidden.

He is torn about reaching out to Ryan Kaneshiro, an old friend who now works at the medical examiner’s office.

The next days bring a shock. A newspaper reports that Jeannette Obermann, a new Austin resident and an enthusiastic Game Night attendee, has been found dead in her car.

Astrid recognizes her and reels at the timing. Detectives Maryam Shariati and Branson Jones arrive and question Astrid about Perry.

Astrid recounts their brief relationship, his reappearance, the fight, and her attempts to check on him afterward. The library’s broken cameras make her story harder to corroborate.

After prolonged questioning, Shariati tells Astrid that Perry is dead. He was found in a rental car on Halloween morning, dead for at least ten hours.

The cause is suspicious but not yet labeled homicide, and Perry’s powerful parents are pushing for answers.

Jonathan meets Ryan at a bar to learn more. Ryan confirms Perry’s full name—Heneage Pericles Bathurst—and hints that the death presents like an overdose.

Hazel comforts Astrid after work, and Astrid finally admits her Swedish persona is fake; she is from rural Iowa and invented the accent years earlier out of insecurity. Perry was the first person she told the truth to, which makes his disappearance and death feel like punishment.

Hazel assures her that grief and shock are distorting everything.

Police return to the library for Jeannette’s case. Hazel is interviewed and recalls playing Clue with Jeannette and noticing Jeannette lingering in her car afterward.

The narrative then fills in Hazel’s past: seven months earlier in Singapore, police raided Hazel’s penthouse searching for Kit, who was suspected of embezzling twenty-five million dollars through his art business. Hazel insisted she knew nothing beyond their private separation and his emotional withdrawal.

During the interrogation, her mother arrived with news that Kit’s plane had crashed over the North Sea.

Back in Austin, Hazel, Astrid, Sophie, and Jonathan compare what they know. Sophie, panicked by detective Hagerty’s attention, confesses her own secret.

After Game Night, Jeannette approached her in the parking lot, claiming she knew Sophie through Sophie’s late partner Jo-Ann Barnes. Jeannette believed Jo-Ann had died in childbirth and that her baby was taken away, so seeing Sophie and Elise alive in Austin made Jeannette suspect Sophie had stolen the child.

Sophie explained that Jo-Ann had asked her to take Elise to protect her from a homophobic family. Jeannette demanded proof and arranged to meet again.

Later that night Jeannette shared her live location, and Sophie found her dead in her SUV. Terrified of being blamed, Sophie wiped her traces from the scene and kept Jeannette’s phone, knowing the last messages would point straight at her.

Hazel decides they must find who killed both Jeannette and Perry. She suspects a link to Kit’s missing cryptocurrency and to a man named Conrad, who is actually Valerian de Villiers living under an alias.

Hazel recruits Jonathan to help her break into Conrad’s home while Jonathan distracts Ryan. Hazel searches Conrad’s private rooms, tries to hack his computer, and finds a French copy of The Fifth Season holding a romantic postcard that hints at international ties.

Conrad catches her, holds a gun to her head, and a struggle follows. Hazel defuses the moment by kissing him, seizes his unloaded weapon, and improvises a cover story when Ryan and Jonathan rush in.

In private, Hazel admits she is investigating Perry’s death and knows Conrad had ties to Perry and Kit. Conrad reveals that Perry invested millions with Kit and lost it, and that Kit’s shadow has been following everyone ever since.

Astrid later visits Conrad. He shows her Perry’s threat messages: photos of Astrid paired with orders that Perry leave Austin or she would be harmed.

Perry hired a private investigator, and Conrad has the results. The supposed medic Tarik Ozbilgin appears on foreign CCTV linked to a suspicious death in London.

Conrad concludes Tarik and a female partner are mercenaries tied to Russian intelligence. They were hunting Kit’s lost crypto key and regarded Perry as a rival who might locate it first.

At the library fight, Tarik used a diversion to place a weaponized fentanyl patch on Perry, making his death resemble an overdose. Jeannette likely saw the same pair after Game Night, texted Sophie her location, and was killed soon after.

Evidence later connects her murder weapon to the library incident.

Detective Hagerty confronts Sophie using phone records. Sophie admits Jeannette approached her, their later meeting turned tense, and she feared complicating the case.

Hagerty warns her but accepts her account. At home, Elise reveals she already knows her true origins.

Mother and daughter finally speak openly, reaffirming their bond.

The wider fallout settles. Jonathan and Ryan reconcile their long-buried feelings and begin a real relationship.

Hazel returns to Singapore with rare books found in Austin. She explains to Detective Chu that Kit converted stolen Bitcoin into priceless antiquarian books, swapped them into her mother’s collection, and hid them in the Austin library during his final days.

The books are surrendered and sold, repaying victims, covering Perry’s losses, and funding scholarships. Hazel adds a donation in Perry’s name.

She then returns to Austin, reconnects with Conrad, and steps into a new life as the library reopens and the remaining questions fade into something the group can finally live with.

Characters

Hazel Lee

Hazel Lee is the emotional anchor of The Librarians, introduced as a recently widowed woman who has chosen the familiar space of her childhood library branch in suburban Austin as a refuge from grief and chaos. Outwardly she appears reserved, competent, and quietly observant, but her internal life is shaped by the unresolved trauma of her husband Kit’s downfall and death.

Hazel’s instinct is to look for patterns and to protect others from being pulled into the kind of devastation she survived in Singapore, which explains both her caution and her growing suspicion about the deaths linked to the library. Her half-finished board game and abandoned puzzle reveal a deeper layer: she is someone who dreams, builds, and tries to create order, but who doubts herself when life breaks the rules.

Across the story she shifts from passive survival to active agency, becoming the group’s strategist and investigator; her ability to stay calm under threat, improvise under pressure, and think several steps ahead is a direct evolution of the life she was forced into with Kit. Hazel’s arc ends not in perfect closure, but in purposeful forward motion—she accepts responsibility for untangling Kit’s legacy and allows herself to begin again with Conrad, suggesting a resilience that doesn’t erase grief but grows around it.

Kit Asquith

Kit Asquith operates in The Librarians more like a haunting force than a present character, yet his choices drive nearly every major conflict. In life he was a charming, high-stakes art dealer whose intelligence and ambition curdled into secrecy and fraud, culminating in the theft of twenty-five million dollars and a disappearance so complete that even his wife never knew the full truth.

His repeated visits to the Austin library and his meticulous swapping of books show a man who planned carefully and thought symbolically, choosing a public, quiet institution to hide something intensely private and valuable. Kit’s relationship with Hazel is defined by emotional distance and compartmentalization: even their separation and prenuptial agreement suggest a marriage where love existed, but transparency did not.

After his death, Kit’s shadow becomes morally complicated—the story does not paint him as a simple villain, because his final act of converting stolen crypto into rare books and leaving a trail that ultimately compensates victims implies guilt, foresight, and possibly a desire for redemption. Kit is thus both the origin of danger and the unlikely architect of repair, embodying the novel’s theme that libraries preserve not just stories but secrets, and that people can be simultaneously loving, flawed, and catastrophic.

Astrid

Astrid is the heart-on-sleeve idealist of The Librarians, someone who is vibrant, theatrical, and eager to belong, but who has been surviving for years behind a self-invented persona. Her fake Swedish accent and fabricated backstory are not shallow quirks; they are armor built from adolescent heartbreak and a longing to be seen as interesting, untouchable, and chosen.

Astrid’s week-long romance with Perry exposes how deeply she wants intensity to mean permanence, and his repeated ghosting hits her at the seam between her real self and her performed one. When Perry dies, Astrid becomes a portrait of shock: her numbness, guilt, and fear of being suspected are less about objective danger and more about the lifelong habit of assuming she is the one who must have done something wrong.

Her confession to Hazel—dropping the accent and claiming her Iowa roots—marks a crucial reclamation of identity; she learns that authenticity can be met with care rather than rejection. Astrid’s grief is also a kind of coming-of-age in adulthood: through understanding Perry’s motives and the threats around him, she reframes their love not as a mistake but as something real that mattered, even if it was brief.

By the end she is still tender and wounded, yet steadier, supported by a community that values her real voice.

Heneage Pericles Bathurst (Perry)

Perry is one of The Librarians’ most tragic figures, a man who enters as a mystery and ends as a revelation. Initially he appears slippery—an English accent, a flimsy tale about researching a film script, and a habit of approaching women through calculated curiosity—yet that same behavior is shown to be partly genuine: he is a library pilgrim, someone who seeks calm and meaning among shelves when his real life is spiraling into danger.

Perry’s vanishing act after his romance with Astrid is not casual cruelty but a desperate attempt to protect her once he realizes he is being hunted for Kit’s missing cryptocurrency. His internal conflict is threaded through his unfinished apology drafts and final letter, which show a man who is both deeply romantic and intensely self-blaming, someone who chooses disappearance over explanation because he believes explanation would only raise her risk.

Perry is courageous but also fatally proud—rather than fleeing or seeking protection, he tries to confront the threat, and that refusal to be helpless leads directly to his murder. His love for Astrid is the story’s quiet proof that sincerity can exist inside messy decisions; even after leaving, he keeps her photo, rereads her recommendations, and defines safety through the memory of her library.

Perry’s death is not just a plot pivot; it is the emotional engine that forces the living characters into truth, solidarity, and action.

Sophie

Sophie is the branch administrator in The Librarians, a woman held together by responsibility, love for her daughter, and a long-standing fear of being exposed. She projects order and pragmatic leadership at work, but privately she carries a secret that shapes her entire nervous system: Elise is not biologically hers, and Sophie took her at Jo-Ann Barnes’s request to shield her from family homophobia.

Sophie’s past makes her hypervigilant, and the anonymous origami notes strike directly at her deepest terror—that she will lose her child and be cast as a criminal rather than a protector. Her decisions around Jeannette’s death show her moral complexity; she does not kill Jeannette, but her immediate instinct is to erase traces of herself before calling for help.

That panic is selfish on the surface and heartbreaking underneath, because it is rooted in a mother’s terror of losing the only family she has left. Sophie is also capable of growth: she ultimately confesses everything to Hazel, Astrid, and Jonathan, trusting community over isolation, and later faces Detective Hagerty with a clearer spine.

Her final reconciliation with Elise, where they speak openly about Jo-Ann and their origins, completes Sophie’s arc from secrecy to chosen truth. She represents the story’s argument that family is not defined by legality or blood alone, but by love backed with sacrifice.

Elise

Elise, Sophie’s daughter, functions in The Librarians as both catalyst and mirror. As a teenager she is observant, sharp, and impatient with half-truths, which makes her a constant pressure on Sophie’s fragile secrecy.

Her presence at Game Night reflects her generosity and capability—she helps run the event with ease, showing she has inherited her mother’s steadiness even if she expresses it more bluntly. Elise’s irritation when Sophie comes home late, and her later insistence on clarity, underline how children sense emotional weather even when adults try to hide storms.

The reveal that Elise already knows the truth about Jo-Ann because of Sophie’s grandmother repositions her not as a sheltered child but as someone who has been quietly carrying her own version of the family story. Her reconciliation scene with Sophie is crucial: Elise accepts her origins without letting them diminish her bond with Sophie, and in doing so she gives the novel one of its most hopeful notes about honesty strengthening rather than breaking love.

Jonathan

Jonathan is the program director at the Austin branch and one of The Librarians’ most quietly layered characters. At work he comes off as awkwardly kind and slightly scattered, the sort of colleague who tries too hard to help and sometimes blunders, as seen when he unknowingly attempts to set Hazel up right after she is widowed.

Underneath that civility, however, Jonathan is wrestling with long-suppressed desire and the fear of rejection that comes from growing up closeted. His rereading of his teenage poem “Closeted” is not nostalgia but self-interrogation; it shows he has been living around the edges of his own truth for years.

Jonathan’s relationship with Ryan Kaneshiro is built on history, longing, and missed timing, and his internal narrative toggles between cautious hope and reflexive retreat. In the mystery plot he becomes a bridge between emotional and practical worlds, using his connections to gather information and putting himself at risk to help Hazel infiltrate Conrad’s house.

Jonathan’s arc is ultimately about choosing courage in intimacy the same way he chooses courage in investigation: he stops letting fear be the author of his life, confronts Ryan’s avoidance, and accepts love in the present rather than as a perpetual almost.

Ryan Kaneshiro

Ryan Kaneshiro, now working at the medical examiner’s office, is a study in guilt and delayed honesty in The Librarians. His quick responsiveness to Jonathan and his willingness to share sensitive information reflect that, beneath his guardedness, he has always been emotionally tethered to Jonathan.

Ryan’s confession later in the story reveals how shame from a hidden high-school relationship shaped his self-image; he believes he does not deserve happiness because he once lacked the bravery to claim it. This self-punishing mindset explains his pattern of circling Jonathan without fully stepping in, turning attraction into a kind of penance.

Yet Ryan is not only reactive—he is also loyal and quietly brave, helping Jonathan despite professional risk and later naming his desires out loud. His arc resolves not by erasing his past cowardice, but by acknowledging it and refusing to let it dictate the future.

When he finally asks Jonathan to spend the night, it is less a romantic climax than a personal re-entry into a life he wants to live honestly.

Conrad (Valerian de Villiers)

Conrad, whose real identity is Valerian de Villiers, arrives in The Librarians as an offstage enigma and gradually becomes a central gravitational force. He is controlled, intimidatingly competent, and deeply entangled in the shadow economy surrounding Kit’s stolen crypto, which makes him both a threat and a potential ally.

Conrad’s immediate readiness to put a gun to Hazel’s head when he finds her in his office shows how dangerous his world is, but his restraint afterward demonstrates calculation rather than cruelty; he wants answers, not chaos. His loyalty to Perry is one of his defining traits—he acts as Perry’s confidant, executor of evidence, and posthumous voice, and his methodical sharing of Perry’s drafts and investigation results shows a man who processes grief through responsibility.

Conrad is shaped by suspicion and survival; because Kit ruined Perry financially, Conrad initially assumes Hazel is part of the danger, and his hardened worldview makes him slow to trust. Yet he is not emotionally barren: he protects Astrid from the full cruelty of Perry’s death, helps piece together the mercenaries’ involvement, and later supports Hazel’s attempt to repair harm through restitution.

By the end, his emerging relationship with Hazel suggests a man learning to live beyond vigilance, allowing affection to coexist with the sharpness that once kept him alive.

Tarik Ozbilgin (the impostor medic)

The man posing as Tarik Ozbilgin in The Librarians embodies the cold professionalism of the external threat. Presenting himself as an army medic during the library brawl, he performs care and authority to control the scene, discourage official reports, and quietly administer the lethal fentanyl patch that kills Perry.

His effectiveness depends on misdirection, exploiting public trust in medical responders and the invisibility of unhoused people to create noise and confusion. Later evidence links him to mercenary work and likely Russian intelligence, indicating he is not motivated by personal vendetta but by contract, strategy, and the pursuit of Kit’s missing private key.

As a character he is deliberately faceless—defined less by biography than by function—yet his calm insertion into everyday spaces like the library makes him chilling. He represents the theme that danger is not always loud; sometimes it wears the mask of help.

Jeannette Obermann

Jeannette is a brief but pivotal presence in The Librarians, a woman whose curiosity and loneliness propel her into fatal proximity with the truth. At Game Night she is bubbly and performative as a “fortune teller,” which suggests someone eager to connect and to remake herself in a new city.

Her real motivation emerges later: she is haunted by unresolved feelings for Jo-Ann Barnes and by the narrative she built from fragments, believing Sophie may have stolen Elise. Jeannette’s confrontation with Sophie is messy but human—her suspicion is wrong, yet her need to know is sincere, rooted in grief and betrayal rather than malice.

She is also brave in a flawed way, choosing to meet Sophie alone and later sharing her location when she senses danger. Her death, sudden and without visible injury, underscores how ordinary people become collateral when they stumble into larger conspiracies.

Jeannette’s role is tragic because she is not chasing power or wealth; she is chasing clarity about love and loss, and that longing places her in the crosshairs of killers who have no interest in her story.

Nainai (Hazel’s grandmother)

Nainai in The Librarians is both a grounding force and a subtle driver of Hazel’s recovery. She nudges Hazel toward routine work at the library not because she minimizes grief, but because she understands the healing value of structure and community.

Her household is a quiet sanctuary—protected by security cameras she installed—yet it is also a place where Hazel sees continuing life in small ways, like Nainai’s absorption in online games or the mundane needs of groceries and flyers. Nainai’s presence reflects a practical kind of love: she does not demand emotional performances from Hazel, but she creates conditions where Hazel can steady herself.

As a character she symbolizes intergenerational resilience, the kind that doesn’t talk much about pain but builds a safe table for it to sit at.

Detective Maryam Shariati

Detective Maryam Shariati is portrayed in The Librarians as sharp, relentless, and attentive to inconsistencies. Her personal history with Jonathan gives her a subtle double edge: she is familiar enough to read him, yet professional enough not to soften.

Shariati’s approach to Astrid’s interview—methodical, prolonged, and pressing for timelines—shows a cop trained to distrust performance, which ironically makes her a natural foil to Astrid’s lifelong habit of performing identity. While she is not a villain, her presence adds pressure and realism to the investigation, reminding the librarians that innocence does not exempt them from scrutiny.

She represents institutional authority that can be both necessary and frightening when you have something to lose.

Detective Branson Jones

Detective Branson Jones plays a quieter counterpart role to Shariati in The Librarians. He is part of the official machinery that closes in after Jeannette’s death, asking for lists, photos, and testimony, and his steadiness underlines the gravity of the case.

Jones is less personally entangled than Shariati, which makes him feel like the neutral face of law enforcement—professional, suspicious by default, and largely unknowable. His function is to widen the net around the librarians, escalating stakes while keeping the investigation grounded in procedure.

Detective Hagerty

Detective Hagerty in The Librarians is the embodiment of Sophie’s dread because he is perceptive enough to sense she is holding something back. His suspicion of Hazel’s timing at the library shows his instinct to look for coincidence as potential causality, a trait that makes him useful but also menacing to innocent people caught near crime.

Hagerty’s confrontation of Sophie later reveals a pragmatic side: once she tells a coherent story, he accepts it without theatrics, focused on the larger truth rather than personal humiliation. He is not framed as corrupt or cruel; instead he represents how the law can feel like a predator when your life contains secrets, even if those secrets were born from love.

Jo-Ann Barnes

Jo-Ann Barnes appears only through memory and consequence in The Librarians, yet she is central to Sophie and Elise’s identities. Jo-Ann was Sophie’s former partner and Elise’s biological mother, a woman who foresaw the danger her homophobic family might pose to her child and entrusted Elise to Sophie.

The lack of a will or formal record amplifies how precarious queer families can become in hostile social contexts, and Jo-Ann’s decisions echo through the present as both a gift and a burden. She represents sacrificial love that extends beyond death, shaping a family structure founded on choice, protection, and trust.

Chimney

Chimney, Jonathan’s cat, is small but meaningful in The Librarians as an emotional stabilizer. In Jonathan’s most vulnerable scenes—when he rereads his old poem, drafts texts to Ryan, and retreats into uncertainty—Chimney is the steady, warm presence that asks for nothing and offers comfort without judgment.

The cat’s role highlights Jonathan’s loneliness and tenderness, reinforcing how much he needs connection and how carefully he has learned to ration it.

Inez and Raj

Inez and Raj, the clerks at the Austin branch in The Librarians, function as part of the library’s lived-in ecosystem. Though they are not deeply individualized in the summary, their inclusion matters because it shows the branch as a workplace full of ordinary rhythms and relationships.

They represent the supportive, routine labor that keeps the library running, which contrasts sharply with the extraordinary danger unfolding around the main characters. Their presence adds realism and community texture, reminding us that this mystery occurs inside a public institution sustained by many quiet hands.

Themes

Grief as a quiet engine of change

Hazel walks into the Austin branch carrying a kind of exhaustion that doesn’t announce itself. She is newly widowed, not seeking a grand transformation but trying to survive the strange immobility that follows loss.

Her aim for “routine more than reinvention” is revealing: grief often makes even small stability feel like a lifeline. Yet routine becomes the very thing that reopens her to the world.

The daily rhythms of desk work, donations, and programs coax her back into contact with other people’s lives, and that contact slowly pulls her toward action. Her grief is also tangled with unfinished business.

Kit’s death is not only emotional absence; it is a moral mystery that rearranges her sense of who she was married to and who she is now. The flashbacks to Singapore show her being treated as collateral to her husband’s crimes, a pressure that makes her doubly bereaved: she loses a spouse and the shared story of their marriage.

When she later investigates Perry’s death and Conrad’s role, this is not a switch into a thriller hero so much as grief refusing to stay passive. She needs answers because the dead keep shaping the living until their stories are faced.

The board game project in her attic mirrors this state. The scattered pieces, half-finished boards, and imperfect rules are a physical version of her inner life—something once imagined with Kit, now stalled, not yet ready to be thrown away.

Even her quick touch of another unfinished puzzle hints that grief is full of paused futures. Hazel’s movement from cautious workday competence to risky investigation shows how mourning can sharpen rather than dull a person.

The loss does not “heal” into forgetfulness; it changes into responsibility, curiosity, and a readiness to step back into human connection at her own pace. By the end, Hazel’s return to Austin and her willingness to begin again with Conrad are not a tidy recovery arc.

They feel more like a negotiated peace with the past: she brings Kit’s story into daylight, makes restitution, and allows herself a life that is not defined only by what ended, but also by what she chooses next.

Secrets, self-invention, and the cost of living behind a mask

Everyone in the story is holding something back, and the plot keeps showing how secrecy is both shelter and trap. Astrid’s fake Swedish identity begins as a teenage defense against humiliation, but it becomes a daily performance that distances her from real intimacy.

The lie isn’t malicious; it’s a survival strategy that got stuck. Her brief week with Perry is intense partly because he sees through it and still stays.

That is the first moment her invented self doesn’t have to do all the work, which makes his later disappearance hurt with extra force. Her eventual confession to Hazel—dropping the accent and naming Iowa as home—reads like a release valve finally opening.

It’s not a moral lesson about honesty as such; it’s about needing at least one relationship where you don’t have to carry your own fiction alone. Sophie’s secret is thornier.

She took Elise at Jo-Ann’s request to protect her from a hostile family, but the situation sits in a socially gray space where love and legality don’t line up. The anonymous origami threats hit her because she already lives with fear of being judged or punished for a decision that felt right at the time.

Her panicked cleanup at Jeannette’s car isn’t excused, but it is made intelligible: in a world where institutions can tear families apart, secrecy becomes a reflex. Jonathan’s secret is quieter still, folded into an old poem and the hesitations around Ryan.

His past closeting shaped his adulthood into caution; even when he wants connection, he still rehearses and erases. Ryan mirrors this with his own buried shame about their teenage relationship.

Their eventual honesty doesn’t arrive through public confession but through a private willingness to stop hiding from each other. On the larger scale, Kit’s hidden actions—cryptocurrency converted into rare books, swapped, and stashed—show secrecy as a form of power.

He engineered his own disappearance from the financial trail, leaving Hazel to deal with the fallout. The story keeps asking what secrets do to relationships: they can protect the vulnerable, build alternate selves, and keep danger at bay, but they also create loneliness and misread motives.

Perry’s death is linked to the secrets around Kit’s money; Jeannette dies because she uncovers Sophie’s hidden past; Astrid suffers because she didn’t know what Perry was truly doing. By resolving several of these secrets through careful, chosen disclosure, the novel suggests that secrecy is not a fixed moral category.

What matters is who is forced into hiding, who benefits from it, and whether truth is shared as an act of trust rather than as a weapon.

The library as a fragile sanctuary and a maker of community

The Austin branch is not just a setting; it is a social organism that offers safety while also exposing how easily safety can fail. In ordinary moments, the library looks like a low-stakes place: patrons browsing, donations being processed, staff chatting about programs.

Game Night embodies the library’s best promise. A dozen strangers gather under horror posters and red lights to play mysteries, and the effect is warmth rather than menace.

People who might never meet elsewhere share tables, snacks, and laughter. The success of the event matters because it frames the library as a chosen community, not a bureaucratic service point.

Hazel, still raw from grief, is welcomed without pressure. Astrid pours her energy into decoration and hosting, seeking belonging herself.

Sophie’s daughter is folded into the work, showing how the place blurs family life and public service. Yet the story also insists that sanctuaries are not invincible.

The cameras don’t work. Donation boxes block the entrance.

A fight erupts near the public computers. These are very mundane failures, but in a thriller context they become dangerous.

The branch offers calm, but it cannot fully control who comes in or what the outside world brings with it. Kit’s cryptic visit before his death suggests the library can even become a hiding place for enormous wrongdoing, simply because it is underestimated.

The building’s openness is what makes it democratic and humane, but also what makes it permeable to harm. Still, the response to crisis shows why such spaces matter.

The staff become a makeshift investigative unit, not because they are trained for it, but because their relationships are already rooted in care. Hazel and Astrid eat sushi and drink wine after closing; that small domestic scene in a work space feels like a statement about what libraries can become for people who need refuge.

The library also connects different worlds—Austin, Singapore, London, queer gaming clubs, art-dealer circles—through the circulation of books, stories, and people. Even Kit’s restitution plan runs through the library’s shelves, making the institution a literal bridge between crime and repair.

The theme’s core is that public spaces are crucial because they allow soft ties to form among strangers. Those ties are what let people step in for one another when something breaks.

The novel doesn’t romanticize the library as pure innocence; rather it presents it as a human, imperfect shelter whose value comes from everyday acts of welcome.

Surveillance, predation, and the feeling of being watched

A sense of watchfulness hangs over the narrative from the first scene, where cameras record Kit’s quiet movements among the shelves. That opening establishes a world where observation is constant but never fully explanatory.

The footage shows what Kit did—testing bindings, swapping books—but not why, and that gap becomes the story’s puzzle. From there, being watched becomes a shared experience across characters.

Hazel checks her grandmother’s cameras because the old fear from Singapore lingers in her body. Sophie finds anonymous origami notes that imply someone knows her private history.

Perry shows up with suspect research questions, then becomes a target of professional hunters. Even the holiday atmosphere of Halloween is edged with unease: costumes, bumper stickers, and staged “mystery” games exist alongside actual danger.

The presence of mercenaries linked to Russian intelligence makes the theme global, not local; suburban Austin is not insulated from international struggles for money and leverage. The fact that Tarik masquerades as an army medic, using the social trust attached to that identity, points to predation thriving under masks of legitimacy.

The broken library cameras amplify the irony: the one surveillance system meant to protect the community fails, while malicious surveillance works perfectly. Threat texts with photos of Astrid reveal that someone has tracked her movements intimately long before she knows she is part of a larger hunt.

This produces a particular kind of vulnerability: the characters can’t tell whether their unease is paranoia or perception until it is too late. The theme is not just about technology or spies; it is about the psychological shift that happens when people sense a hostile gaze on their lives.

Sophie’s frantic wiping of fingerprints after Jeannette’s death comes from the belief that the investigative gaze will not be kind or nuanced. Hazel’s cautiousness in the library, and her later decision to break into Conrad’s house, show a move from passive fear to active counter-surveillance.

She becomes someone who watches back. Yet the novel keeps acknowledging the moral risk of that move.

Entering Conrad’s rooms in a balaclava is effective but also a boundary crossed under pressure. By connecting surveillance to both danger and survival, the story suggests that being watched is a form of power that can be used to protect, to control, or to destroy.

The crucial question becomes who controls the frame of interpretation. Cameras and data don’t carry truth by themselves; they are tools in conflicts over narrative.

Ultimately, the hunt for Kit’s private key and the deaths around it show surveillance as a modern form of warfare that can reach into any life, even into a quiet library aisle, and turn ordinary routines into sites of risk.

Love, loyalty, and ethical choices under pressure

Relationships in the novel are defined less by romance as fantasy and more by loyalty tested in stressful circumstances. Astrid and Perry’s connection starts in flirtation and speed, but what gives it weight is the mutual recognition of vulnerability.

Perry is drawn to her even after the accent drops; Astrid trusts him with her real self. His later reappearance without explanation is a betrayal of that trust, yet the story complicates it by revealing he was trying to protect her from threats tied to Kit.

His drafts of apologies, and the fact that he kept her photo as his lock screen, underline that love can coexist with terrible judgment. Sophie’s love for Elise is the most morally charged form of loyalty.

She once acted in a moment of devotion to Jo-Ann and to a child’s safety, then continues to protect Elise by any means available. Her decision to clean the crime scene is ethically wrong and she knows it, but it is driven by a fear that the system won’t understand her love.

The novel doesn’t ask the reader to approve; it asks the reader to see how love can push someone into desperate calculation. Jonathan and Ryan illustrate another angle: love constrained by old shame.

Their bond is slowed by years of self-protection, the kind that grows in people who learned early that desire could cost them safety. When Ryan finally confesses the guilt that kept him orbiting Jonathan, their relationship turns on mutual insistence that love should not be a punishment.

Hazel’s emerging feelings for Conrad are similarly tied to trust in unstable ground. She breaks into his home and is met with a gun to her head; their later connection is possible only because she is willing to confront him with truth, and he is willing to treat her as a partner rather than a suspect.

On the broader moral plane, loyalty also appears in restitution. Hazel doesn’t simply recover Kit’s hidden wealth; she channels it into repayment, compensation, and scholarships.

That is a form of loyalty to the living as much as to the dead, an insistence that love for Kit cannot mean excusing his harm. The story repeatedly places characters in situations where they must choose between loyalty to a person and loyalty to a principle.

The most striking examples show that ethical clarity is hardest when love is involved. People aren’t corrupted by affection; they are motivated by it, sometimes into courage, sometimes into errors.

By ending with repaired relationships rather than perfect innocence, the novel argues that loyalty is not proven by being flawless. It is proven by what people do after fear and love collide—whether they retreat, lie, or step forward to protect others without losing their own integrity.