The Life-Changing Magic of Falling in Love Summary, Characters and Themes

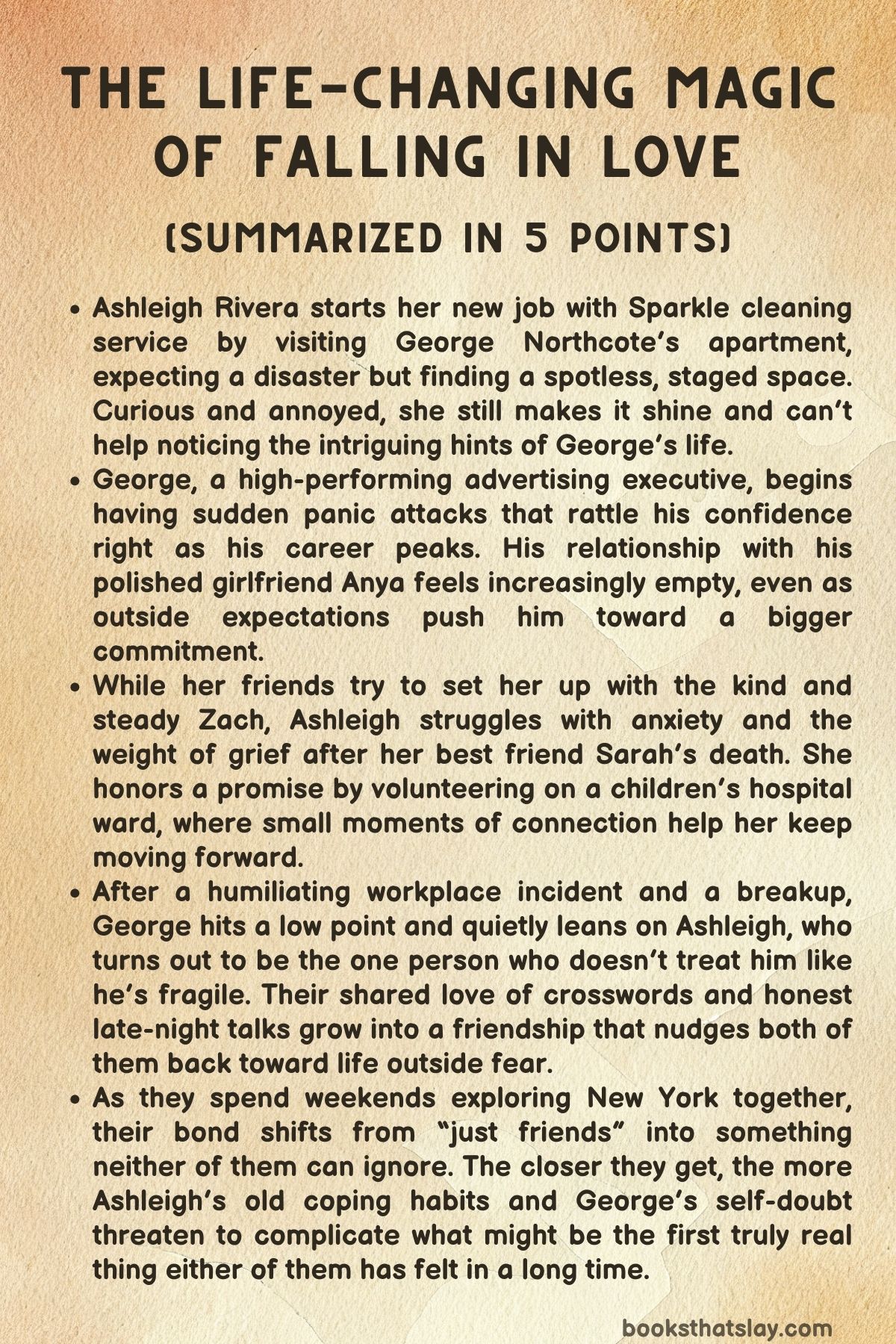

The Life-Changing Magic of Falling in Love by Eve Devon is a contemporary romantic comedy about two anxious, bruised-by-life New Yorkers who stumble into each other’s orbit in the most ordinary way: through a cleaning appointment. Ashleigh Rivera is rebuilding herself after grief derailed her career and confidence.

George Northcote is a high-achieving ad man whose controlled life is cracking under panic attacks and a fading relationship. When Ashleigh starts cleaning George’s spotless apartment, their cautious friendship grows into something that nudges them both back toward risk, connection, and the kind of love that feels like choosing life again.

Summary

Ashleigh Rivera shows up for her first job at Sparkle Cleaning Service expecting chaos and a solid paycheck. The client file promises a weekly deep-clean for Apartment 33C, the kind of place that usually needs hours of scrubbing.

Instead, she steps into a pristine, minimalist showpiece that looks more like a catalog spread than a lived-in home. Everything is polished and arranged with near-clinical precision, right down to the bare countertops and carefully positioned furniture.

Ashleigh double-checks the address, mutters about being lied to, and tries to make an already spotless apartment “sparkle” just to justify her visit. The only hint of a personal life is a framed photo of a glamorous couple at a wedding in Sicily.

The man resembles her client, George Northcote, and Ashleigh can’t help noticing how magnetic he looks.

While she works, Ashleigh gets a call from her mother, who is already pressuring her about family expectations and an upcoming cousin’s wedding. Cornered by yet another lecture about being single, Ashleigh blurts out a lie: she has a date that night.

The claim soothes her mother but leaves Ashleigh annoyed with herself, her nerves, and the empty apartment that somehow feels judgmental in its perfection.

Across town, George is in the middle of a make-or-break advertising pitch for Yeong Cosmetics. He’s the steady star of his agency, chasing a long-awaited promotion, and he needs this meeting to go flawlessly.

Then his body turns against him. Heat, dizziness, and tunnel-like hearing hit without warning.

He forces himself through the presentation while his heart races and the room seems to tighten. The campaign lands, the client approves, and the deal is celebrated—right before George bolts out of the conference room in terror, convinced he is dying.

Outside the building, he collapses. At the hospital he’s told it wasn’t a heart attack but an anxiety episode, an answer that terrifies him almost as much as the symptoms did.

That night his girlfriend, Anya, comes home from celebrating the victory without him. George is hurt that she didn’t visit, but she brushes the incident off, praising him for pushing through and warning him not to dwell on it.

Their conversation settles into a familiar pattern: efficient, careful, and oddly distant. George notices how little comfort he actually feels with her, even when they are trying to be kind to each other.

Ashleigh’s world is smaller and messier. She lives in a modest apartment, works long shifts, and leans on her best friends Carlos and Oz, who run the bakery downstairs.

Carlos is determined to get her dating again, and after a string of dull experiences she reluctantly agrees to meet Zach Weldon, a friendly engineer with a broken ankle and a self-deprecating charm. Their first dinner is awkward at the start—Ashleigh is frazzled, late, and drops hints about “George” without meaning to.

But Zach stays patient and amused, and by the end of the night Ashleigh feels a cautious spark of possibility. A second date goes even better; they share a sweet, clumsy kiss, and Ashleigh rides home hopeful.

Still, anxiety sits close to her skin. She calms herself the way she always has: by cleaning and ordering her space until her breathing slows.

She collects white feathers found on sidewalks and in doorways, treating them as small signs that she is on the right path. She also wrestles with another promise—volunteering as a reader on a children’s hospital ward, something her late best friend Sarah pushed her into before dying suddenly in an accident.

Ashleigh hates the hospital’s smell and the guilt that comes with it, but she shows up anyway. She reads to a young patient, Katey, and afterward talks quietly with Nurse Nadine, who knew Sarah.

Nadine’s steady kindness helps Ashleigh accept that grief may always return, but it can be carried.

George, meanwhile, receives his promotion to Senior Account Manager. The news should feel triumphant, but the added expectation triggers another anxiety episode.

He clings to his crossword puzzle as a lifeline, remembering his grandfather’s childhood advice to seize the day. Anya gives him an expensive watch to celebrate, but she’s too busy to actually celebrate with him.

George tells himself work matters more, yet loneliness keeps creeping in.

Their lives collide properly when George spirals at the office. Jealous and exhausted, he misreads a moment between Anya and coworker Tim Duggins, then explodes during a client meeting, humiliating Tim and himself.

The scene ends with George shaking and breathless in front of his team. Anya coolly announces they already broke up the week before.

The combination of shame, heartbreak, and another public anxiety episode leaves George wrecked.

Ashleigh finds him afterward and—despite barely knowing him beyond cleaning his apartment—listens without flinching. She brings a small gift, teases him about his obsession with order, and lets him talk.

George confesses how numb the breakup feels, how scared he is of being seen as fragile, and how much he dreads attending his brother’s wedding alone. In return, Ashleigh finally shares her own most humiliating memory: when grief and pressure pushed her into a disastrous magazine shoot that ended with her fainting on her boss and losing her career.

Saying it aloud in George’s presence cracks something open in her. For the first time, the story feels survivable.

The agency forces George to resign, with Anya stepping smoothly into his role. Ashleigh refuses to let him disappear into his immaculate apartment.

She drags him outside for ice cream, music shops, and touristy weekends, determined that he experience New York as a person, not a worker hiding behind routine. Their friendship grows through banter, shared crosswords, and a steady recognition that they understand each other’s fear.

On a rainy Saturday trip to Governors Island, tension finally breaks. Ashleigh admits she’s been offered a promotion at Sparkle and is terrified of failing again.

She also worries George will bury himself in work and anxiety. George snaps back that he isn’t her project, that he wants a full life—and that what he feels for her is not friendship.

The argument flips into honesty, and under the downpour he kisses her. Ashleigh kisses him back, surprised by how right it feels.

George goes to the UK for his brother’s wedding, and their connection deepens through constant messages and late-night calls. Ashleigh begins dreaming forward again, even clearing out Sarah’s old room as a way to make space for what’s next.

When George flies home, Ashleigh panics at the airport when he doesn’t appear right away, only to crash into him the moment she sees him. George reveals he’s pursuing a job at Memorial hospital, inspired by Ashleigh’s idea that healing can leave visible, beautiful seams.

He tells her he wants this future because he chooses it, not because she pushed him.

They admit they’re falling in love, openly and without hedging. Months later, they share an apartment, their lives braided together in daily warmth.

The bakery thrives, Carlos and Oz get engaged in a joyful burst of community celebration, and George gives Ashleigh another white feather—now less a sign of rescue and more a quiet symbol of the life they’re building on purpose, together.

Characters

Ashleigh Rivera

Ashleigh is the emotional heart of The Life-Changing Magic of Falling in Love—a woman rebuilding herself after loss while trying to stay functional in a life that often feels like it’s slipping out of her control. On the surface she’s bright, chatty, and competent at her cleaning job, but the summary shows that her tidiness isn’t just professionalism; it’s a coping mechanism.

When anxiety spikes, she cleans, folds, organizes, and curates her surroundings until her breathing steadies, which reveals how deeply she relies on external order to manage internal chaos. Her grief over Sarah’s death sits underneath almost every decision she makes: volunteering at the children’s ward is less about altruism at first and more about guilt, loyalty, and fear of failing a promise.

Ashleigh’s romantic arc also mirrors her emotional healing. She begins wary, judgmental of boredom or arrogance in others, but not because she’s shallow—she’s terrified of investing in someone and losing them again or losing herself.

Her developing bond with George works because it grows through honesty, shared vulnerability, and small rituals (crosswords, weekend plans), and her eventual willingness to choose love despite fear marks her main transformation. Even her promotion subplot reinforces this: Ashleigh is learning to step into a bigger, messier life without needing everything to be perfectly controlled first.

George Northcote

George is a high-achieving, restrained man whose carefully curated life is actually a fragile defense against panic, loneliness, and old wounds. His immaculate apartment, minimalist style, and insistence on “sparkle” aren’t just preferences; they signal a need for predictability and safety.

The sudden panic attacks during high-stakes moments show how much pressure he carries to be “fine,” competent, and unbreakable, especially because of his repaired childhood heart defect. He tries to rationalize symptoms, push through presentations, and minimize his mental health, which makes his collapse feel both inevitable and heartbreaking.

In relationships he has been coasting rather than living—his time with Anya is built on compatibility and career orbiting rather than passion—so their breakup forces him to confront how numb he’s become. George’s jealousy-and-noodles meltdown exposes his fear of being replaceable and unloved, but also how badly he wants something real.

His connection with Ashleigh becomes a turning point because she doesn’t pity him or treat him like a project; she challenges him while still staying present. By the end, George isn’t just falling in love—he’s choosing a life with spontaneity, community, and emotional risk, symbolized in his move toward a hospital job inspired by healing and kintsugi.

Anya

Anya is portrayed as polished, ambitious, and pragmatic—someone who expresses love through shared goals and career partnership rather than emotional intimacy. She is not a villain, but she is emotionally misaligned with George.

Her first reaction to his collapse is efficient and controlling: she labels it a panic attack, reframes it as manageable, and urges him not to let it “get in his head. ” This suggests she sees vulnerability as something to handle quickly so it doesn’t interfere with performance, which fits her broader identity as a driven advertising professional.

The relationship’s distance is clear in small details: she celebrates the deal without visiting him, keeps prioritizing events and launches over time together, and even when she helps with his campaign, it’s framed as protecting their shared future at work. Her breakup is strikingly calm and logical—she realizes she feels no jealousy and concludes their love is absent—showing she values clarity over clinging.

Anya’s promotion into George’s role after his firing also underlines her career momentum and the gulf between their emotional needs. She represents a life George could keep performing in, but not one where he can truly heal or be seen.

Carlos

Carlos functions as Ashleigh’s loud, affectionate anchor and comic realist, but he’s also a protective friend with his own fears. He pushes Ashleigh toward dating partly because he believes she deserves happiness, yet his matchmaking is also a way of pulling her back into life after grief.

His teasing and nosiness hide genuine concern: when Ashleigh begins falling fast for George, Carlos panics because he knows how fragile she still is after Sarah’s death. His argument with her shows a moral boundary he won’t cross—he refuses to let her romantic hope become another uncontrolled leap that might shatter her.

At the same time, Carlos is not emotionally perfect; his stress about the bakery and relationship with Oz makes him sharper and more defensive than usual. By the end, his own engagement shows that his belief in love isn’t just something he pushes on others; he’s living it too, and that steadiness helps normalize Ashleigh’s path.

Oz

Oz is quieter in the summary but consistently reliable, acting as both a stabilizing force for Carlos and a gentle supporter of Ashleigh. He participates in the double-date plan and bakery life with warmth, but his deeper role emerges when his stress spills out and he later apologizes, revealing self-awareness and emotional responsibility.

Oz recognizes Ashleigh’s artistry in her feather collages and encourages her to see value in them beyond private comfort, which shows his ability to notice people’s hidden strengths. His proposal to Carlos in the final scene reflects his romantic boldness and his faith in building a shared future, paralleling the main couple’s commitment.

Oz represents grounded love: not flashy, but intentional and brave.

Zach Weldon

Zach begins as the “safe option,” a kind, normal man introduced to pull Ashleigh back into dating without overwhelming her. His broken ankle and humble moon-boot entrance immediately frame him as approachable and unthreatening, and his easy humor around Ashleigh’s clumsiness demonstrates patience rather than judgment.

He respects her job as a cleaner and meets her with curiosity instead of condescension, which is important for Ashleigh’s bruised confidence. Still, Zach’s role is not to become her great love; he’s a bridge.

Their connection is genuine but limited by timing and emotional depth: Ashleigh isn’t ready to fully open, and Zach’s life rhythms (weekends with his mother, talk of moving home) don’t align with the future Ashleigh starts to imagine. He matters because he proves to Ashleigh that tenderness is possible again, making her eventual leap toward George a choice, not a rebound.

Hildegard “Hildy” Lundy

Hildy is a catalyst character who pushes both Ashleigh and George toward emotional honesty. As Ashleigh’s older client and George’s neighbor, she occupies a semi-maternal role, but she’s not soft-spoken; she’s blunt, observant, and allergic to overthinking.

With Ashleigh, she sees anxiety before Ashleigh says a word and insists she follow through on the hospital volunteering, effectively forcing Ashleigh to face grief instead of circling it. With George, she provides recurring nudges about romance and life balance, challenging his habit of hiding behind work and solitude.

Her women-only tea parties and emphasis on women taking a “seat at the table” show she’s socially conscious and quietly radical, someone who has spent a lifetime creating spaces where others grow bolder. Hildy’s humor and meddling make her lovable, but her deeper function is belief—she believes these two people can survive love, and she keeps pushing until they do.

Sarah

Sarah is physically absent but emotionally central, serving as the ghost that shapes Ashleigh’s fears and motivations. Their friendship was a place where Ashleigh felt understood and alive, and Sarah’s sudden death during a scaffolding accident becomes the origin point of Ashleigh’s anxiety, guilt, and self-doubt.

Ashleigh’s career collapse after Sarah’s death shows how grief can destabilize identity, and the humiliating rabbit-photoshoot incident is tied to Ashleigh trying to prove she’s still capable of brilliance while internally unraveling. Sarah also drives Ashleigh’s volunteering promise, which becomes one of the first steps toward healing.

In a way, Sarah remains a companion to Ashleigh’s arc: not as a chain holding her back, but as a love that Ashleigh must learn to carry without letting it stop her life.

Nadine

Nadine appears briefly but meaningfully as a compassionate professional who helps Ashleigh reframe grief. Her recognition of Ashleigh from Sarah’s funeral instantly links present healing to past loss, but Nadine doesn’t push sentimentality; she offers steady, clinical kindness and language that normalizes grief as waves rather than a failure to “move on.

” By walking Ashleigh out and talking her through the emotional whiplash of volunteering, Nadine becomes a quiet proof that people can survive sorrow and still function. She’s less a plot driver and more a grounding voice that helps Ashleigh keep returning to the ward.

Joey

Joey, Ashleigh’s brother, is mostly a supportive background presence, but his teasing reveals a family dynamic that’s loving, informal, and slightly intrusive. He mirrors the kind of everyday attachment Ashleigh still has despite her independence: someone who jokes, nags, and keeps emotional tabs on her without needing a serious confrontation.

His role is to show Ashleigh isn’t alone in the world even when she feels isolated, and his encouragement of her relationship with Zach (and later acceptance of the shift toward George) suggests the family wants her joy more than they want control.

Harrison Richards

Harrison is the embodiment of professional authority and pressure in George’s life, intensifying George’s anxiety even when offering praise. As George’s boss and Anya’s father, he blurs personal and corporate boundaries in a way that makes George’s panic feel trapped inside a glass box—literally and socially.

His promotion offer triggers another panic attack because it represents not just achievement but heavier expectation, and his hinting about marriage to Anya shows how much George’s private life is being evaluated through workplace politics. When Harrison later fires George despite apology and illness, he demonstrates the agency’s priority: image and stability over humane understanding.

Harrison isn’t cruel for cruelty’s sake; he’s the kind of leader who feels justified by business logic, making him a realistic antagonist to George’s need for patience and recovery.

Tim Duggins

Tim is less a full character and more the trigger for George’s collapse, but even in that role he’s important. George’s obsession with Tim reflects fear, insecurity, and a tendency to catastrophize under stress.

Tim’s hand-holding with Anya is innocent in context, suggesting Tim likely isn’t malicious, but the event becomes a mirror showing George how unstable he’s become. Tim also witnesses George’s exit, reinforcing George’s humiliation and sense of being publicly broken.

He’s a symbol of the life George thinks he’s losing—status, respect, control—rather than a true personal rival.

Julia

Julia functions as a small but telling window into the building’s community and into Hildy’s influence. Through her children, her patience with noise, and her explanation of Hildy’s networking teas, Julia shows how Hildy has built a supportive ecosystem around her.

She also indirectly helps George’s creative breakthrough by talking about women taking confidence and “a seat at the table,” which sparks his Perfect Pies campaign idea. Julia’s presence reinforces the theme that healing and inspiration often come from ordinary human connections.

Abigail

Abigail is seen through George returning a dinosaur and hearing her violin practice. She serves as part of the noisy, lived-in world outside George’s sterile apartment.

Her violin playing, even if annoying, symbolizes life happening messily around him, and George’s interaction with her household shows him practicing patience and care in small ways. She’s a minor character, but she contributes to the atmosphere of community that nudges George toward a fuller life.

Davey

Davey, Julia’s younger child who struggles with goodbyes, helps reveal George’s gentle side. George uses his watch timer to help Davey cope, showing that beneath his tight control and anxiety, George is thoughtful and good with people who need reassurance.

Davey’s small moment underscores a theme of repair and support—George can help others through fear even when he struggles with his own.

Katey

Katey is a child patient on Ladybug Ward and the first person Ashleigh reads to as a volunteer. Her role is crucial for Ashleigh’s internal shift: Ashleigh enters the ward trembling, but Katey’s quiet responsiveness proves that Ashleigh can show up to pain without breaking.

Katey represents the living stakes of Ashleigh’s promise to Sarah and reorients Ashleigh’s grief into care rather than paralysis.

Tina

Tina appears only through family talk, but she sets a social pressure cooker around Ashleigh. Her upcoming wedding becomes the reason Ashleigh lies about a date to her mother and later asks Zach to be her plus-one.

Tina represents the louder family expectation of normal milestones—dates, weddings, coupledom—that Ashleigh feels unready for, making her eventual ability to attend weddings with George feel like a reclaimed part of life rather than an obligation.

Jasmine

Jasmine’s wedding is another milestone event that frames Ashleigh’s emotional trajectory. Even without much detail, it’s a test of Ashleigh’s new beginnings: she brings Zach as a sign of reentering romance, and the aftermath of that wedding is what exposes the unresolved attraction between her and George.

Jasmine’s role is structural—her wedding is a hinge point where Ashleigh’s old caution shifts toward risky happiness.

Tiny

Tiny is not a character in the speaking sense, but in Ashleigh’s retold trauma he becomes a symbolic force. The rabbit’s panic and chaotic escape during the photoshoot mirrors Ashleigh’s own mind under grief, stimulants, and pressure.

Tiny’s presence helps explain why Ashleigh now spirals when control slips; her humiliation and breakdown were tied to trying to force beauty and order onto a life that had already shattered. In the emotional logic of the story, Tiny is a reminder of the moment Ashleigh lost faith in herself—and thus a shadow she must outgrow.

Robert

Robert begins as a ficus Ashleigh brings George, but evolves into a shared symbol of their relationship. For George, caring for the plant is gentle responsibility, a small living thing that grows in his once sterile space.

For Ashleigh, naming it and seeing it survive links to her broader belief in healing after damage. When they live together and the plant still has a place, it quietly signals that their love is being tended, not just felt.

Themes

Grief, anxiety, and the slow return to living

Ashleigh’s daily life is shaped by loss long before romance takes center stage. Sarah’s sudden death doesn’t sit in the story as a single tragic backstory moment; it is a continuing force that tightens around Ashleigh’s choices, habits, and sense of safety.

Her anxiety is shown as physical routine: she cleans to quiet her mind, she orders her space into calmness, and she clings to small rituals like collecting white feathers. These aren’t quirky traits but survival strategies, a way to feel a little control when the world has already proven it can break without warning.

The promise to volunteer on the children’s ward is another strand of grief: it pulls her toward a place that hurts, yet it also becomes the first honest step she takes toward rejoining life. She doesn’t arrive there brave or healed; she arrives scared, almost turning away, then stays anyway.

That matters because the book treats recovery as a set of choices made while still afraid, not as a clean transformation after fear disappears.

George’s panic attacks run parallel to Ashleigh’s grief. His body reacts to pressure and uncertainty in ways he can’t hide, and the story refuses to frame that as weakness.

The advertising world expects polish, composure, and constant performance, so his panic becomes a private humiliation, especially when it spills into public view. Both characters are trapped by the fear that their inner fractures make them unlovable or unreliable.

Ashleigh worries that moving forward betrays Sarah, while George worries that his heart history and anxiety label him as fragile. Their friendship creates a space where those fears are spoken without punishment.

When Ashleigh finally tells George about the rabbit photoshoot disaster, she is not asking to be rescued; she is testing whether the ugliest version of her story can be handled by someone else. His quiet presence, even while falling asleep, gives her a kind of acceptance she hasn’t been able to offer herself.

In The Life-Changing Magic of Falling in Love, healing isn’t about forgetting what happened or proving strength. It’s about letting another person witness the mess that grief and anxiety leave behind, and then choosing to keep showing up anyway.

Control, cleanliness, and the search for stability

From the first scene in Apartment 33C, the story makes cleanliness more than scenery. George’s home is spotless to the point of being impersonal, and Ashleigh’s disappointment at finding nothing to scrub is layered with meaning: a clean apartment is supposed to be a simple job, but here it’s a puzzle.

The extreme order suggests someone trying to outrun chaos, and later we learn that’s exactly what George is doing. His need for control isn’t vanity or fussiness; it’s a defense against panic.

If everything is aligned and predictable, maybe his body won’t betray him again. That logic is fragile, of course, because panic doesn’t obey neatness.

The more he tries to seal his life into perfection—promotion targets, a girlfriend who fits his professional world, an apartment that looks staged—the more pressure builds behind the seal. His public collapse after the Yeong pitch is a direct crack in that system.

Ashleigh uses control differently but for the same reason. Cleaning isn’t only her job; it is the lever she pulls to move her nervous system back into balance.

When she is scared about her date with Zach, she doesn’t text a friend or journal. She scrubs her kitchen and folds laundry until her breathing settles.

Control is tactile for her. It’s also emotional: she tries to pre-plan outcomes so she won’t be blindsided again, whether by romance, work, or grief.

Her fear of the Sparkle promotion is telling. Management means unpredictability, responsibility for other people’s mistakes, and less time to rely on her soothing routines.

Even good change feels dangerous because it threatens the systems that keep her upright.

The theme grows richer when the two meet in the middle. Ashleigh initially sees George as a “neat freak” client who wastes her time, but her irritation shifts once she recognizes the vulnerability inside that order.

George, meanwhile, starts to unlearn the belief that stability comes only from rigid control. Their weekend sightseeing isn’t just cute dating; it is practice in leaving the safe, curated interior of his apartment and letting life be messy, random, and sometimes rainy.

The kiss in the downpour lands on this theme perfectly: control drops away, and connection happens precisely when their plan collapses. The Life-Changing Magic of Falling in Love suggests that order can protect, but it can also imprison.

Real stability comes not from keeping everything spotless, but from trusting that you can handle the spill when it comes.

Love as a choice that asks for honesty and risk

Romance here is not presented as a lightning bolt that fixes everything. Ashleigh’s first attempts at dating are cautious, half-hearted, and influenced by other people’s agendas.

The date with Zach begins because Carlos wants her to “get back out there,” and Ashleigh treats it like a test she expects to fail. Zach is kind, steady, and genuinely interested, yet Ashleigh can’t stop orbiting George in her mind.

This isn’t because she wants drama; it’s because her heart is already waking up, even while she tries to keep it under control. Her anxiety around kissing Zach, around weekends alone, and around letting herself hope again shows that love feels risky after loss.

She doesn’t trust happiness to last, so she keeps rehearsing how it could go wrong.

George’s relationship with Anya shows the opposite kind of risk avoidance. They are successful, functional, and impressively aligned on paper, but the relationship is built more on momentum than emotional truth.

Their conversations circle work, status, and shared professional goals, not the raw interior parts of themselves. When Anya ends it, she identifies the absence of passion rather than a dramatic betrayal.

George has been living inside a version of love that requires minimal exposure, and the breakup forces him to face how empty that kind of safety can feel. His meltdown with Tim, though humiliating, is a twisted form of honesty: it reveals how much he actually cared, and how deeply he feared being replaceable.

Love with Ashleigh grows out of friendship and mutual witnessing. Their crossword habit matters because it is intimate without being romantic at first.

It lets them build trust through small, repeated acts. When George admits his panic attacks and job loss, Ashleigh doesn’t manage him or pity him; she stays.

When Ashleigh confesses her past collapse at Best Home magazine, she does it without polish, and George receives it without flinching. That creates the emotional ground on which romance can stand.

Their argument on Governors Island is a turning point because it strips away the protective labels of “just friends. ” George risks rejection by naming attraction directly, and Ashleigh risks emotional exposure by admitting how she interpreted his restraint.

The decision to kiss is less about sudden impulse and more about finally telling the truth they’ve been circling. By the end, commitment is framed as an active choice: they say out loud what they want, they plan shared futures, and they move in together not as a grand fantasy but as a step built on honesty.

The Life-Changing Magic of Falling in Love treats love not as rescue, but as a brave agreement to be seen fully and to keep choosing each other even when fear is loud.

Identity, self-worth, and work that doesn’t define you

Both protagonists begin with identities tied tightly to performance. George’s self-worth is welded to career success.

He has climbed toward Senior Account Manager for years, and the promotion feels like proof that he is secure, impressive, and safe from the vulnerabilities he carries. The advertising world rewards composure and constant ambition, so his panic attacks strike at more than his health; they strike at the story he tells himself about who he is.

His public implosion with Tim and the forced exit from the agency become an identity crisis. Without the role, he has to confront the question of what remains.

The fear that people will treat him differently because of his heart history reveals how much he equates capability with control and status. Losing his job is awful, but it also creates the first opening for him to consider a life that isn’t shaped entirely by fear of falling behind.

Ashleigh’s work identity is complicated in another direction. She once aimed for a glamorous design career, and the collapse at Best Home magazine left her convinced she doesn’t belong in that world anymore.

Cleaning is both a practical job and a quiet punishment she accepts for herself. She is good at it, takes pride in it, and even finds peace through it, but she still carries shame about “ending up” there.

Zach’s respectful response when she says she is a cleaner is a small but important correction to that shame. The Sparkle promotion forces another recalibration: leadership could validate her skill, but it also feels like a trap because it might confirm that this is all she is now.

Her panic over the new role reflects a deeper question: is she allowed to grow into a new self without erasing the old one Sarah knew?

Their relationship helps both disentangle worth from work. Ashleigh challenges George’s reflex to hide inside a draining job, not to control him but because she sees how work has become his shield.

George, in turn, sees Ashleigh’s talent for curating spaces as real craft rather than consolation. Oz’s suggestion that she sell her art pushes this further, because it treats her creativity as alive, not dead.

By the end, George chooses a hospital-related path inspired by meaning rather than prestige, and Ashleigh builds a service idea that blends her skill with her own vision. The theme doesn’t argue that work is unimportant; it argues that being valuable isn’t conditional on a title, a salary, or a past failure.

In The Life-Changing Magic of Falling in Love, love becomes one of the things that lets people step out of narrow definitions of success and rebuild a self that feels honest.

Community, friendship, and the way people carry each other

The romance would not exist in the same way without the strong social web around the couple. Carlos and Oz are more than side characters who provide comic relief; they function as a mirror and a push.

Carlos’s insistence that Ashleigh date again comes from loyalty and worry, not meddling for sport. Even when his delivery is messy, his fear is rooted in love for her and in the memory of Sarah.

His later conflict with Ashleigh about George shows a real ethical tension: friends want to protect you, but they can also accidentally hold you in place. That fight matters because it proves the friendship is strong enough to survive truth and anger.

Oz’s quieter support—apologizing for snapping, praising her collage, hinting at a future she hasn’t dared to imagine—offers another kind of care, steady and affirming.

Mrs. Lundy and Hildy serve as community catalysts, nudging both Ashleigh and George toward action when they want to freeze.

Hildy’s blunt advice about not overcomplicating romance isn’t always subtle, but it comes from experience and an unembarrassed belief that people deserve joy. The women-only tea parties she hosts, framed as giving women confidence to take a “seat at the table,” underline a broader communal goal: helping others claim space in life.

Even the hospital ward scenes add to this theme. Nadine’s short conversation with Ashleigh carries a kind of institutional kindness; she doesn’t fix grief but normalizes it, giving Ashleigh permission to keep living while still missing Sarah.

For George, neighbors and coworkers also shape his path. The building corridors, the violin practice, the toy dinosaur errand, and the casual chats all keep him in a human world when he’s tempted to isolate.

After his firing, Ashleigh bringing soup and dragging him out for ice cream isn’t only romantic care; it is community in action, a refusal to let someone disappear into shame. The JFK welcome-home moment makes the theme explicit.

People show up with silly signs, nervous excitement, and real affection, and that collective presence becomes part of the love story’s foundation. The final scene of Oz proposing to Carlos in a crowded bakery circles back to this idea: love is celebrated and sustained in public, among people who have been there through the hard parts.

The Life-Changing Magic of Falling in Love presents community as the net under personal change. It doesn’t erase pain or make decisions for the characters, but it provides enough warmth and pressure that they keep moving forward instead of turning inward.