The Little Liar Summary, Characters and Themes

Mitch Albom’s 2023 novel The Little Liar presents a gripping tale of love, guilt, and survival set against the devastating backdrop of the Holocaust. It follows four characters, all deeply affected by the lies and manipulations that defined their wartime experiences.

Narrated by Truth itself, the story begins in the coastal town of Salonika, Greece, and traces the lives of Nico, Sebastian, Fannie, and Udo over the span of nearly 50 years. Each character endures the horrors of World War II in different ways, but their lives are forever intertwined by the lasting impact of deception.

Summary

Set in the Jewish community of Salonika, Greece, The Little Liar follows the intertwined destinies of four characters through the brutal years of the Holocaust and into its long, haunting aftermath.

The narrative spans from 1936 to 1983, revealing how lies—both intentional and forced—shape lives forever. The story is uniquely narrated by a personified Truth, guiding readers through the emotional turmoil of those caught in the web of deceit and survival.

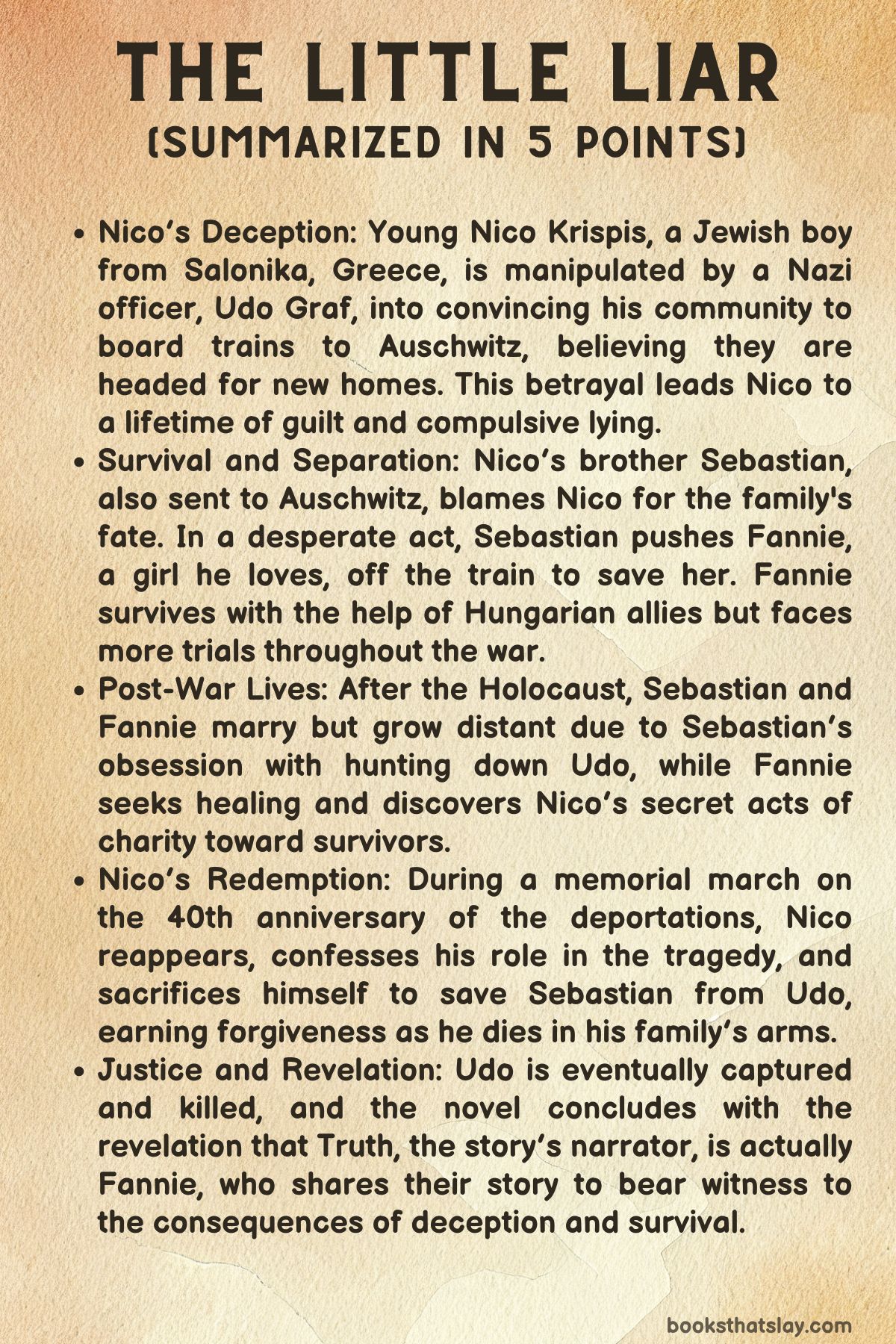

At the heart of the novel is Nico Krispis, a young Jewish boy known for his honesty. But when the Nazis invade Greece, his life is torn apart.

He encounters a German SS officer, Udo Graf, who deceives him into helping spread lies to the Jewish population. Udo promises Nico that if he convinces others to board trains to their supposed “new homes,” he will reunite Nico with his family.

Unwittingly, Nico becomes a pawn in Udo’s scheme to facilitate the mass deportation of Salonika’s Jewish population to Auschwitz. The boy, thinking he is helping, watches in horror as his own family is among those herded onto the trains destined for the death camps.

This moment breaks Nico, and he becomes incapable of telling the truth ever again.

Meanwhile, Nico’s older brother, Sebastian, who also ends up on the train to Auschwitz, blames Nico for the family’s destruction. In a desperate moment, Sebastian tries to save Fannie, Nico’s classmate and a girl he loves, by pushing her off the train. Fannie survives and is sheltered by a kind Hungarian woman, Gizella, until she is eventually discovered.

Just as she faces execution at the Danube River, she is saved by Nico, who, driven by guilt, has been traveling under different aliases to save those he can. They are aided by the Hungarian actress Katalin Karády, who orchestrates the escape of 24 Jewish children, including Fannie.

However, Fannie is later recaptured and spends the rest of the war hiding with refugees.

After the war, Sebastian, consumed by anger, dedicates his life to tracking down Udo, who has slipped away to hide in the U.S. while working under a false identity.

Meanwhile, Fannie and Sebastian marry and have a daughter, but their relationship frays as the years pass.

Sebastian’s relentless quest for revenge drives them apart, while Fannie is drawn toward healing, returning to her roots and eventually discovering that Nico has been secretly helping Holocaust survivors.

Sebastian’s quest leads him to Udo, but their final confrontation is interrupted during a memorial march on the 40th anniversary of the Salonika deportations.

At this moment, Nico reappears and confesses to his role in the tragedy, but insists Udo is the true villain. Udo tries to kill Sebastian, but Nico sacrifices himself to save his brother, earning forgiveness in his final moments.

In the aftermath, Udo is caught and poisoned in a symbolic act of justice, orchestrated by Fannie.

The novel ends with Nico’s story coming full circle, as Sebastian and Fannie watch videos he recorded, revealing the tragic complexity of his life.

Ultimately, the story closes with the revelation that Truth, the narrator, is actually Fannie, determined to share the pain and the lessons of their collective history.

Characters

Nico Krispis

Nico Krispis is the central figure in The Little Liar. His transformation from an innocent, truth-telling boy to a guilt-ridden, pathological liar encapsulates the novel’s theme of deception and its impact on the human psyche.

At 11 years old, Nico is manipulated by Udo Graf, a German SS officer, into playing a pivotal role in the deportation of Salonika’s Jewish population, including his own family. Nico’s initial belief in Udo’s promise to reunite him with his loved ones, followed by the crushing realization that his actions have condemned them to death, marks the beginning of his lifelong battle with guilt and shame.

His inability to cope with the horror of his inadvertent betrayal leads him to reject truth entirely, becoming a man who hides behind various identities. This internal conflict persists throughout his life as he attempts to atone for his past by secretly helping survivors and seeking redemption through his actions.

In the end, Nico’s willingness to sacrifice himself for Sebastian signals his ultimate desire to reconcile with the truth. This occurs despite the years of lies and deception that have defined him.

Sebastian Krispis

Sebastian, Nico’s older brother, presents a different response to trauma. His experience in Auschwitz, witnessing the death of his family members, hardens him and fosters a deep resentment toward Nico for his perceived role in their demise.

This bitterness consumes him, driving a wedge between him and Fannie, the woman he loves, and pushing him toward an obsession with seeking justice, or perhaps vengeance, against Udo Graf. Sebastian represents the survivor who struggles to move forward from the atrocities of the Holocaust, unable to let go of the past.

His obsession with hunting Udo reflects his need for closure and his belief that the only way to heal is through retribution. While he is successful in exposing Udo’s true identity, his personal life suffers as he distances himself from his wife and child.

However, in the final moments of the novel, when Nico sacrifices himself to save Sebastian, Sebastian is finally able to forgive his brother. This marks a significant shift in Sebastian’s character as he comes to terms with both the past and his future.

Fannie

Fannie’s character serves as a voice of moral fortitude and resilience throughout the novel. She is not only a survivor of the Holocaust but also someone who endures significant personal trauma, including being pushed off the train to Auschwitz by Sebastian, the man who later becomes her husband.

Despite her harrowing experiences, including her time in hiding and eventual recapture, Fannie emerges as a figure who seeks meaning in her survival. Unlike Sebastian, whose focus is on retribution, Fannie is more concerned with remembering and honoring the past through compassionate means.

Her decision to revisit Gizella, the woman who saved her, and her pursuit of Nico are driven by a need for understanding rather than revenge. Fannie’s journey reflects the moral complexity of survivors, particularly those who must navigate the post-war years with the weight of memory and loss.

In the end, Fannie reveals herself as the narrator of the story, personifying Truth. This narrative choice suggests that Fannie’s role is to bear witness and ensure that the story of the Holocaust and its aftermath is told with honesty and clarity, even when that truth is painful.

Udo Graf

Udo Graf is the antagonist of the story, representing the cruelty and moral bankruptcy of the Nazi regime. His manipulation of Nico sets in motion the tragic events that lead to the destruction of Salonika’s Jewish community.

Udo is portrayed as both a calculating and sadistic figure, relishing in the power he holds over the lives of the Jewish prisoners. His promotion to oversee the death camps reflects his deep commitment to the Nazi cause and his lack of remorse for the suffering he causes.

Udo’s ability to evade capture after the war, hiding in plain sight as a member of a senator’s staff in the United States, further illustrates the failure of post-war justice to immediately hold all war criminals accountable. Despite his initial escape from Sebastian, Udo is eventually brought to justice in Germany, though his ultimate fate—poisoned by Fannie—is a form of poetic justice delivered outside the legal system.

Udo’s character embodies the inhumanity of the Holocaust, and his death signifies the end of his reign of terror over the Krispis family.

Katalin Karády

Though a secondary character, Katalin Karády plays a crucial role in the salvation of several Jewish children, including Fannie. A Hungarian actress who uses her status and connections to aid the Jewish resistance, Katalin represents individuals who, at great personal risk, defied the Nazis to save lives.

Her character is based on a real historical figure, which adds a layer of authenticity to the novel’s portrayal of resistance efforts during World War II. Katalin’s relationship with Nico also offers insight into his post-war life, as she becomes a key figure in Fannie’s search for him.

Her willingness to help Fannie find Nico years after the war illustrates her enduring commitment to the people she saved. It also highlights her understanding of the importance of reconciliation and closure.

Gizella

Gizella is a minor yet significant character in the novel, representing the ordinary individuals who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. Her decision to hide Fannie and care for her for several months demonstrates the quiet heroism of those who resisted the Nazi regime in small but profound ways.

Gizella’s role in Fannie’s survival highlights the importance of solidarity and compassion during times of atrocity. Her actions serve as a counterpoint to the betrayal and lies that permeate much of the novel.

Although her part in the story is brief, Gizella’s impact on Fannie’s life is long-lasting. Fannie later returns to her in an attempt to reconnect with her past and understand the role that others played in her survival.

Themes

The Complex Interplay Between Guilt, Responsibility, and Redemption

One of the most profound themes in The Little Liar is the intricate relationship between guilt, responsibility, and redemption, particularly as it relates to the Holocaust and its aftermath.

Mitch Albom presents characters whose lives are forever marked by the decisions they made, either through active choices or under coercion.

Nico Krispis embodies the central figure of this moral dilemma—his youthful naivety and trust are weaponized by Udo. In being manipulated into deceiving his own people, he inadvertently becomes complicit in the deaths of thousands, including his own family.

His transformation into a pathological liar is not merely a coping mechanism but a manifestation of his profound guilt, one that haunts him for decades.

Sebastian, Nico’s brother, serves as a counterpoint to Nico’s internalized guilt. His outward rage toward Nico represents the complexity of survivor’s guilt and the difficulty of assigning blame in situations so permeated by manipulation and deceit.

Sebastian’s obsession with hunting Udo reflects a misplaced attempt at redemption, as if bringing Udo to justice could somehow undo the damage done to his family.

Throughout the narrative, Albom interrogates the idea of whether true redemption is possible for someone like Nico.

His eventual death while protecting his brother from Udo’s bullet suggests a form of atonement, but it leaves the question open as to whether such a moment can erase decades of suffering and lies. Redemption, in this novel, is as elusive and complicated as the guilt that precedes it.

The Manipulation of Truth and the Destructive Power of Lies

The personification of Truth as the narrator of The Little Liar underscores the significance of truth-telling and deception in the novel.

From the outset, the narrative grapples with the destructive power of lies and the far-reaching consequences that falsehoods can have on individual lives and entire communities.

Nico’s transformation from a boy who had “never told a lie” to a man who cannot stop lying illustrates how deeply deception warps his sense of self and distorts the world around him. His lie—albeit told under duress—sets off a chain reaction of suffering and destruction, showing how the Nazis weaponized deception as a tool of mass murder.

This theme extends beyond Nico’s lies to the lies that the Nazis told, both to their victims and to themselves. Udo, as the embodiment of Nazi cruelty and manipulation, uses lies as a tool to carry out genocide with cold efficiency. But the novel complicates this theme by suggesting that deception is not a one-way street; it also infects the minds and souls of those who use it.

Udo’s eventual unraveling and paranoid need for revenge against Sebastian and the Nazi Hunter reveal the toll that his own lies have taken on him. By contrast, Nico’s eventual decision to reveal the truth at the march and sacrifice himself to save Sebastian points to the redemptive potential of honesty, though it comes at an immense personal cost.

Albom ultimately presents truth not as an abstract moral ideal, but as a force with immense destructive and healing potential, depending on how it is wielded.

Survival and the Moral Ambiguities of Holocaust Trauma

Survival in The Little Liar is depicted as both a physical and moral challenge, fraught with ethical ambiguities and personal betrayals. The characters’ experiences of survival during and after the Holocaust raise difficult questions about what it means to endure unimaginable horrors while retaining a sense of humanity.

Sebastian’s decision to push Fannie off the train to save her life is an act of love. However, it also highlights the impossible choices that survivors often had to make. Fannie’s own journey through hiding, capture, and eventual escape further underscores the precariousness of survival and the constant presence of death.

The novel also explores the psychological and emotional toll of survival. Sebastian’s obsession with Udo and the pursuit of justice, Fannie’s desire to reconnect with her past and help others, and Nico’s self-imposed exile from the truth all reflect the various ways that trauma manifests in the lives of Holocaust survivors.

These characters are not simply survivors in the physical sense; they are also haunted by the moral compromises and emotional scars left by the war. Albom complicates the typical narrative of survival by suggesting that the end of the war does not signify an end to the trauma. Instead, survival comes with its own set of burdens and ethical dilemmas that continue to plague the characters long after the camps are liberated.

The Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma and Memory

The Little Liar also addresses the theme of intergenerational trauma, particularly in how the Holocaust continues to affect the descendants of survivors. Sebastian and Fannie’s daughter, Tia, represents the second generation, who inherit the emotional and psychological legacies of their parents’ experiences.

Though Tia is not a direct witness to the horrors of the Holocaust, the trauma her parents endured profoundly shapes her life and her relationship with them. The march that Sebastian organizes to commemorate the victims of Salonika, in which Tia participates, symbolizes the weight of memory that the second generation must bear.

Albom’s exploration of this theme is particularly poignant in the final chapters, when Truth reveals that Fannie is the narrator of the story. This revelation shifts the narrative from a broader reflection on the Holocaust to a deeply personal account of one woman’s attempt to grapple with the legacy of trauma.

By framing the story through Fannie’s perspective, Albom underscores the importance of memory and storytelling as a way of preserving the past and ensuring that future generations understand the full scope of what was lost and what was endured. However, the novel also raises questions about the limitations of memory, as Fannie’s version of events is inevitably shaped by her own perspective, emotions, and the passage of time.

Thus, The Little Liar suggests that while the transmission of memory is vital, it is also fraught with its own challenges, as the act of remembering is never entirely objective or complete.